The Art Institute of Chicago’s major summer exhibition, John Singer Sargent and Chicago’s Gilded Age, is probably a crowd-pleaser–though I haven’t checked the numbers. Sargent is usually a big draw–I remember when, to cite one example, the show of his watercolors at the Brooklyn Museum outdrew a large show of El Anatsui, which was a surprise given Brooklyn’s predilection for contemporary art (in which, I’d say, El Anatsui is a rock star).

The Art Institute of Chicago’s major summer exhibition, John Singer Sargent and Chicago’s Gilded Age, is probably a crowd-pleaser–though I haven’t checked the numbers. Sargent is usually a big draw–I remember when, to cite one example, the show of his watercolors at the Brooklyn Museum outdrew a large show of El Anatsui, which was a surprise given Brooklyn’s predilection for contemporary art (in which, I’d say, El Anatsui is a rock star).

But Sargent has been exhibited so many times–except in Chicago, where decades had passed since his last exhibition. What to do that’s different? If you are Art Institute curator Annelise K. Madsen, you find a local angle. She decided to organize an exhibit of works by Sargent that had been exhibited in Chicago, owned by Chicagoans, or portrayed Chicagoans. It was a good idea, I thought.

Then she went a step further and married that with a narrative about the desire of locals to make Chicago’s cultural scene match its industrial prominence, and to set Sargent in that scene among his artist friends and rivals.

Then she went a step further and married that with a narrative about the desire of locals to make Chicago’s cultural scene match its industrial prominence, and to set Sargent in that scene among his artist friends and rivals.

Not a bad idea, on first thought–though for me, it didn’t quite work. I was in Chicago several weeks ago to review it for The Wall Street Journal, and my piece was published in today’s print paper, headlined, Dazzling Art With a City Connection.Â

It’s a good show, as I wrote:

With this exhibition arranged thematically rather than chronologically, visitors see Sargent in the round, one facet at a time. The need for a Chicago connection, however, prevents it from being a true retrospective, as many of his best paintings, like “Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose†(1885-86), have no such link and are thus absent.

That was still ok, as the exhibit is “full of visual pleasures.” For me, the bigger issue was Madsen’s decision to add in works by Sargent’s friends and rivals.

That was still ok, as the exhibit is “full of visual pleasures.” For me, the bigger issue was Madsen’s decision to add in works by Sargent’s friends and rivals.

…— Claude Monet, Giovanni Boldini, James McNeill Whistler, Anders Zorn, Dennis Miller Bunker and Walter Gay, among them. Hung both interspersed with Sargents and in a gallery of their own—constituting a third of the paintings on view—they often serve the Chicago-rising narrative, but seem like interlopers. The “Sargentesque†ones can be confusing. Less—or none—might have been more.

Maybe that is a real problem for all double-narrative exhibits. There aren’t that many to begin with. and maybe there’s a reason for that.

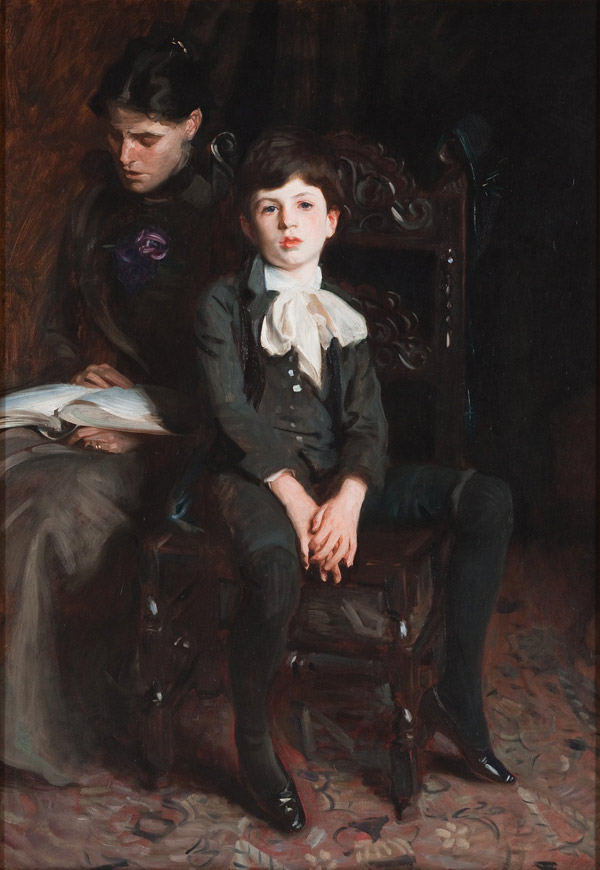

Let me be clear, though: the exhibit is still very much worth seeing–as the two works, Portrait of a Boy and The Loggia, Vizcaya, pasted here indicate, Up top is a picture I took of three ladies studying La Carmencita. Who could ask for more?