Hedda Sterne is not a name you hear very often, so I was pleased last spring when I learned that the Amon Carter Museum of American Art was giving her a solo exhibition. It would be a small one, and of lithographs, not paintings, but still I wanted to see it. We’re in a moment when female artists are getting a bit more museum exposure, and I wondered about her.

Hedda Sterne is not a name you hear very often, so I was pleased last spring when I learned that the Amon Carter Museum of American Art was giving her a solo exhibition. It would be a small one, and of lithographs, not paintings, but still I wanted to see it. We’re in a moment when female artists are getting a bit more museum exposure, and I wondered about her.

At one time Sterne was prominent–mostly, though, she was prominent now for having appeared in Life magazine’s photo of The Irascibles–the only woman among the artists in the photo, all of whom had signed a letter to the president of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in May, 1950. As she once explained, she arrived at the staged session late, after photographer Nina Leen had placed everyone, so Sterne was put up on a table, standing, on the right, sticking up “like a feather.” (Several others, male and female, had signed the letter, but were not in the photo.)

But, according to hearsay, Sterne was the only woman because she invited herself when her husband, Saul Steinberg, was called to be in the photo.

For more information about that letter–and the exhibition in question–you might read a fascinating account by Robert Beverly Hale, then associate curator of American Painting and Sculpture. It’s online on the Met’s website. Here’s an excerpt:

On May 20, 1950, an open letter signed by eighteen painters and ten sculptors was received by the Museum. It stated in substance that they “rejected the monster national exhibition” to be held at the Metropolitan, that the juries chosen were too conservative to admit a just proportion of advanced art. It called upon all the advanced artists in the country to boycott the exhibition.

This letter, which appeared on the front page of The New York Times, stirred up a spirited controversy. On June 12 the Museum received an open letter signed by seventy-five artists expressing confidence in the integrity of the juries appointed, saying that it seemed unfair to attack the juries before they had met and announced their verdicts.

As an aside, it’s interesting to note some artists who were in that exhibition: Ivan Albright, Andrew Wyeth, Everett Spruce and Mark Tobey are among them.

But back to Sterne: She later blamed the photo for causing her trouble with male artists, but she wanted the attention. Even though she hung around with the art crowd, including Duchamps and Mondrian at first and’, later, the guys at the Cedar Tavern, she still, early on, felt that she would be better off signing her work only with a “H,” to disguise her gender.

But back to Sterne: She later blamed the photo for causing her trouble with male artists, but she wanted the attention. Even though she hung around with the art crowd, including Duchamps and Mondrian at first and’, later, the guys at the Cedar Tavern, she still, early on, felt that she would be better off signing her work only with a “H,” to disguise her gender.

That soon ended, but there’s no question that her connection with Steinberg aided her.

For me, Sterne’s work is uneven. She experimented a lot–working in Surrealism, abstraction (both geometric and biomorphic), representation, portraiture. But she never developed a particular signature style or niche.

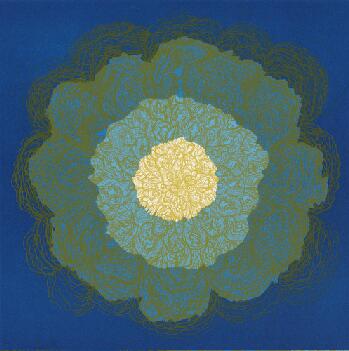

The works on view at the Amon Carter are from two series (plus four miscellaneous prints)–Metaphores and Metamorphoses and The Vertical Horizontals–that she made in 1967. I reviewed the exhibition for The Wall Street Journal, published in yesterday’s paper.

The prints are engaging, interesting–a window on her thinking, her working out process. But they didn’t leave me asking for more. I have seen her very good painting at the Tate, and a few others. The Met plans to put one of her paintings in Epic Abstraction, coming this fall–if it is the one in the museum’s permanent collection, I don’t believe it’s normally on view.

And so, despite this wide-ranging look at Sterne’s work, I had to conclude–for the show and for her in general:

“Hedda Sterne: Printed Variations†is a small, attractive show displaying themes that she also explored in painting. It leaves her where she will probably remain in art history, closer to the periphery than the center.

Photo Credits: Courtesy of Nina Leen/Time Life Pictures Gallery/Getty Images (top right); Metaphores and Metamorphoses VII, bottom left, courtesy of The Hedda Sterne Foundation.