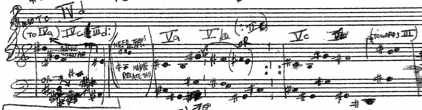

I’m almost done transcribing and analyzing Dennis Johnson’s November, the ostensively six-hour 1959 piano piece that La Monte Young says inspired him to embark on The Well-Tuned Piano. I’ve listed some of November‘s innovations elsewhere. If it was indeed the first multi-hour continuous minimalist piece, the first tonal very slow work, the piece that pioneered additive process – and it may have been all that – those in themselves are enough to make it worth reviving and getting into the history books. But beyond that, I’ve become more and more impressed with its internal logic, which is almost mathematical (and Johnson left music to become a mathematician). The piece is organized into families of motifs based on the same pitches, which can proceed improvisatorily to other families of motifs at specified points. Johnson begins each new pitch field additively, bringing in one note or chord, then another, then another until they’re all present. But the overall formal concept is not simply additive but more like a series of circles, as each pitch field has a point of entry and exit, and within each section one can go back and forth among the motifs in that field. It’s really elegant, and in its glacial way makes a certain large-scale sense to the ear. Feldman’s wonderful masterpiece Triadic Memories (a much later work, 1981) is similar in its reminiscent effects and equally intuitive, but November is generally diatonic rather than chromatic, and its logic lies a little closer to the surface. I thought that in September Sarah Cahill and I would be re-premiering a kind of crazy, off-beat experiment of the late ’50s; instead I’m thinking we’ll be unveiling a whole new formal paradigm that deserved to have more of an after-history than it’s had.Â

Search Results for: www.kylegann.com

Drawing the Connections

Back in Evanston, Illinois, in the early ’80s, I used to know Evelyn Becker, the widow of composer John J. Becker. Becker is the member of the “American Five” that you can never think of, unless you also can’t remember Wallingford Riegger. Riegger was a Communist, and Mrs. Becker reported that he had scandalized her by writing John letters that began, “Dear Comrade….” “After all,” she shuddered, “we were good Catholics!”

In 1933-34, John Cage moved to New York at Henry Cowell’s advice, to study with Adolph Weiss – but also found himself playing cards with Weiss and Wallingford Riegger. In 1941, a 15-year-old Morton Feldman studied with Riegger. And later in 1952 or ’53, Riegger took a sabbatical replacement position at Manhattan School of Music, where a young Robert Ashley was pursuing his Master’s degree. Ashley and Riegger both had apartments on the East Side, and ended up taking the same bus to school every day. Riegger was the first composition teacher Ashley had found sympathetic, and Ashley remembers being the only kid in class interested in the 12-tone techniques Riegger was teaching. Riegger wrote an astonishing Study in Sonority in 1928, more radical to my ears than anything Schoenberg had yet done, and attractive Third and Fourth Symphonies and a Piano Concerto all in a 12-tone idiom, and also a beautifully retro Canon and Fugue in old-fashioned D minor.Â

I’m not a real music historian, but I’m a sufficiently enthusiastic fake one to get a kick from knowing and drawing these connections. We don’t think, for example, of Cage and Ralph Shapey inhabiting the same scene, but at some point circa 1950 they, along with Feldman, were drawn into the orbit of Stefan Wolpe; and ten years later, we find Wolpe and Cage hobnobbing with Cage’s New School student Toshi Ichiyanagi and his new bride Yoko Ono. Someday there will be a book on James Tenney, who studied with Varese, befriended Ruggles, argued with Partch, made psychedelic eletcronic music with Mort Subotnick, played in the ensembles of Steve Reich and Phil Glass, taught alongside Harold Budd, and taught Peter Garland, Larry Polansky, John Luther Adams, and Michael Byron, among many others. Tenney is a line wandering through American musical history, drawing a variety of unexpected connections. The people most central to American music, those who can’t be pulled out of the fabric without it unraveling, are not always the household names.Â

And so interviewing Ashley (12 hours so far this week) is one of the most exciting things I’ve ever done. He doesn’t like reminiscing about the past – he thinks I should concentrate on his most recent ideas – and doesn’t realize how quietly the history of 20th-century music falls into focus as he tells me about all the contacts he made in his youth. (One thing I learned – Luciano Berio was a wealthy man from the beginning. Why? Heir to the Berio olive oil fortune. I think of Berio every time I see that olive oil in the grocery store, but never knew the connection. [And it’s not true, as it turns out, but Bob, who knew Berio for forty years, thought it was.]) Yesterday, Ashley told me:

“The only thing that’s interesting to me right now is that, up to me and a couple of other guys, music had always been about the eventfulness: like, when things happened, and if they happened, whether they would be a surprise, or an enjoyment, or something like that… It’s about eventfulness. And I was never interested in eventfulness. I was only interested in sound. I mean, just literally, sound in the Morton Feldman sense…. There’s a quality in music that is outside of time, that is not related to time. And that has always fascinated me… That’s sort of what I’m all about, from the first until the most recent. A lot of people are back into eventfulness. But it’s very boring. Eventfulness is really boring.”

It reminded me strongly of when, years ago, La Monte Young showed me his early string quartet in which the five movements are all almost identical, and I asked him why, and after a moment’s musing he responded, “Contrast is for people who can’t write music.” When I quote that there are always people who get defensive and agitated about it, but for many of us, that’s just our aesthetic. It’s not going to replace Mozart, and you’ll still get to hear Stravinsky, and there’s no reason to think that our saying that is the end of the world, and that we have to be smothered, or stopped, or else we’ll bring the whole edifice of culture crashing down. For some of us, eventfulness is boring, contrast is unnecessary, and we’re interested in the aspects of music that don’t relate to time. And the fact that we moved to that in a single generation from Riegger and Wolpe, and that these important threads can be teased out of history, is a tremendously thoughtful pleasure.

UPDATE: McLaren points out in comments that Riegger’s Study in Sonority isn’t currently available in any form. So here it is.Â

Delayed Gratification

…is my middle name. Lucky I have a glacial attention span. After 15 years of working intermittently with the Relache ensemble, I finally got to hear the rest of my Planets last night, and I’m so happy with them. I’m posting mp3s for all the movements, at least until the recording comes out in the fall. There are a few patches from rehearsal takes due to note flubs and one violent stream of audience coughing:

Online Articles Lost to Memory

Chicago critic Marc Geelhoed nicely noted my upcoming return to Chicago, and in so doing, noted that some eleven of my articles for the Chicago Reader, starting from 1987, are available online. I had no idea. In fact, I’d forgotten that I continued writing for the Reader so long after I joined the Village Voice, up through spring 1989 – just three months before I left Chicago for good. I’ve linked the available articles from my web site (scroll down a little, the titles are in green) – interviews with Harold Budd, Peter Gena, Elodie Lauten, Nicolas Collins, Henry Gwiazda, Neil Rolnick, and others. Not of much interest to others after 20-odd years, but the Reader always makes me sentimental. In some ways I always thought it was the best organization I ever worked for, and my editor there, Pat Clinton, was a saint.Â

Reconstructing Harold

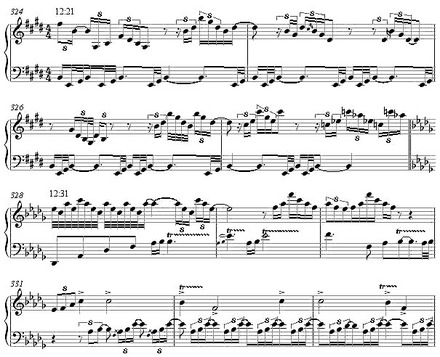

Here’s a brief audio sample from Harold Budd’s Children on the Hill, the improvisatory piece I’m transcribing from a 1982 perfomance for reconstruction on our upcoming Minimalism conference. At 23 minutes in length, it’s a completely different piece than his eponymous performance on the old Obscure CD. The beginning and end were easy to transcribe, but in the middle of the piece is a wildly rhapsodic wash of arpeggios that goes on for 13 minutes. I can slow down the soundfile to catch all the notes, but slowing down also blurs the note attacks, and makes low notes in particular less distinct. So what I end up doing is transcribing the general outlines as far as I can at normal speed, slowing down to 50 or 60 percent to catch all the treble arpeggios, then slowing that down another 50 percent to decipher grace notes and disentangle rippling arppeggios, then listening to the whole thing sped up again – which often reveals mistaken rhythms as well as mis-heard bass notes. Of course, it’s not just normal piano, but piano played through an Eventide Harmonizer, which blurs the notes and makes them sound like they’re sustained or played again, which doesn’t make transcription any easier. I’d say I’ve been spending at least three hours on every minute of the recording, and I’ve got seven minutes left to go. Below is my transcription (so far) of the passage above. Of course, rhythms are kind of a humorous fiction in a rapidly improvised passage like this, so the pianist (Sarah Cahill) will have to ignore the meter, play in an unmeasured rush of excitement, and listen to the original recording to try to capture the original expression. Next to this, the transcription work I did on The Well-Tuned Piano was a piece of cake, but Harold’s music is so beautiful that it’s going to be totally worth it.Â

What 2009 Sounds Like, Symphonically

Here is the recording of Robert Carl’s Symphony No. 4 (2009) that I promised you, with Christopher Zimmerman conducting the Hartt School Orchestra. The opening is very quiet. I’ll play it for my “20th-century” Orchestral Repertoire class this week – I just love giving them as much of the 21st century as possible.

End of an Experiment

Like millions of others, I’m feeling the effects of the financial downturn, and, looking around for expenses I can cut down on, my eyes light on PostClassic Radio. The cost of running it has doubled since I started it (to over $600 a year), and I haven’t had time to replenish the playlist lately anyway. I know there are some devoted listeners, to whom I’m grateful, but the listening statistics aren’t very impressive – anywhere from 2 to 20 listening hours a day lately, with the average around 9. I can still put up mp3 music examples on my web site when I need to. I’m proud of my playlist, which I will leave up as a repertoire of hundreds and hundreds of postclassical pieces since 1970, and thankful to all the musicians who allowed me to play their work. Subsidizing the music of others was an important thing to do when I started it, but I don’t think it’s a cost-effective strategy anymore, and I’d appreciate not having that hole in my budget next month. Don’t worry, I won’t quit the blog, which costs me nothing. Thanks to all those who listened (it’ll be up for a few more days if you’re trying to record things), and let’s look forward to the next phase.

The Symphonic Temperament

Friday I drove to Hartford to hear the Fourth Symphony of one of my oldest friends. It sounds strange to say that: Fourth Symphonies are written by dead composers in the history books, or at least by gray eminences who are living out their fame in European seclusion. But it’s true, my old chum Robert Carl has written four of them now, the latest played by the Hartt Symphony Orchestra under conductor Christopher Zimmerman. Robert is chair of composition at the Hartt School of Music.

Robert and I keep trying to remember how we met, which was almost thirty years ago, but we can’t pin it down; he was finishing his doctorate at the University of Chicago, I across town at Northwestern. Aesthetically, we come from rather opposite sides of the tracks, but our lives keep intersecting and paralleling. We’re both transplanted southerners. He studied with Ralph Shapey, and as a critic at the Chicago Reader I championed Shapey (somewhat to the chagrin of my NU music professors) and published a long interview with him, which I still think is good enough to reprint someday. Robert also studied with George Rochberg, whom I’ve found myself championing lately, enough to receive thanks from his widow. We both had brief student experiences with Morton Feldman. I used to write for Fanfare magazine, as Robert does now, which I believe I got him into (or was that Scott Wheeler?). I just completed a book on Cage’s 4’33”, and Robert is about to publish one on Terry Riley’s In C, on the basis of which we’ve invited him to give a keynote address at the Minimalism Conference at UMKC next September (of which, more news soon). And luckily, Robert and I both moved east to schools only a couple of hours apart and both deeply appreciate fine bourbons and single-malt scotches, so you can imagine the rest.

Generally speaking, Robert’s music is far more angular and dissonant than mine, and oriented toward Romanticism rather than Minimalism, but that superficial characterization is misleading. A few years ago I gave a paper for an Ives festival on younger composers influenced by Ives, and Robert was, if not Exhibit A, at least B or C – and we certainly have that much in common. Robert’s music covers a wide stylistic range, with occasional forays into jazz harmony, minimalism, and even Downtown-type sound installation, but he does have a central, most quintessential style which I can only describe in terms of yearning and transcendence. He has little relation to the music that most people would call New Romanticism, even less to neo-, but there is in his music a kind of aspiration to transcend mundane things, such as one might find parallels for in late Beethoven, Messiaen, Ives’s quieter moments like the finale of his Fourth Symphony – and perhaps in Shapey. Robert’s and my educations and preferences overlap considerably, but we’re opposite personality types: I write a cool, steady music in an attempt to calm myself down, and he writes a music of feeling so urgent that it seems to want to burst the boundaries of its sonic container – perhaps to heat himself up? Between the two of us, he is certainly the more easy-going personality.

I think it’s taken Robert a long time to clarify what is truly Carlesque in his music amid the Ruggles-like angularity (his dissertation was on Sun Treader), the Ivesian layering, the Rochbergian style schisms, the Shapeyesque pitch usage, and it’s been exciting to hear it emerge ever more clearly in each new work. His Fourth Symphony was his clearest, most incisive work yet. It was 23 minutes long, in five movements played continuously, though easy to hear as a varied one-movement work. The opening alternated between soft chords in the strings and winds and a jaunty rhythmic texture in the percussion, and you could eventually tell that the string chords were trying to grow, to turn into a theme, against the percussion’s complacent interruptions. This drew the audience into the work by giving us something to identify with and root for. Impressively, the piece built up its argument without the usual continuity devices of themes or (as in so much minimalist-based work) ongoing propulsive patterns, but through textural blocks juxtaposed against one another in a kind of architectural choreography. It’s a technique unrelated to the usual American styles, and I think ends up in what one might call East-European territory. Unlike comparison pieces by Erkki-Sven Tüür, Aulis Sallinen, and others, however, every gesture was musical rather than sonic, if you know what I mean; Robert never goes for abstract effects, but couches each texture with lyrical specificity, and his sense of rhythm is entirely American. It’s a very original work, so engaging that it seemed to go by too quickly, and I’m looking forward to hearing the recording, which I’ll post here for you to hear it too. [UPDATE: Here it is.]

Robert thinks this is the best he’s done at creating a multimovement “symphonic argument” that emerges over the course of the piece. I certainly hear what he means, as I intuit what it means in symphonies by Beethoven, Bruckner, Mahler, Nielsen, and that crowd. I think it’s probably not something I could come up with myself. I haven’t written a symphony, but I secretly consider my Transcendental Sonnets a choral symphony, and my Implausible Sketches for two pianists the symphony I didn’t bother to orchestrate. From those and my clarinet sonata I gather that I feel multimovement form as a group of fairly self-contained movements all related to a center – more than a suite, the order not arbitrary, but not really symphonic, either. The only other friend of mine who writes symphonies, I think, is Gloria Coates (15 so far), and she doesn’t really aim for that sense of cumulative development either. (My friend Peter Garland got so tired of waiting for an orchestra commission that he wrote a long, wonderful symphony for flute, clarinet, and trombone.) My pieces each gradually explore a soundworld that’s felt to be all present from the beginning, which I guess means my music is more about being, and Robert’s is about becoming. Perhaps that sense of becoming, separable into stages, is what’s needed to be a real symphonist. In any case, I’m proud to have such a long-time friend adding original examples to a true symphonic repertoire.

The melancholic, the sanguine: me and Robert Carl (photo by his partner, the sculptor Karen McCoy).

Top Six Reasons to Wander in the Wilderness

1. the strangeness of some of the intervals, which give me the thrill of hearing phenomena that I can’t (as a music theory teacher all too used to analyzing music by ear) automatically process and label;Â

2. the stretching of one’s pitch perception toward harmonics higher than the fifth (since the decision to stop with the fifth harmonic was an arbitrary academic mandate of the Italian 17th century);Â

3. the ability to have lots of pitch variety within a very small space (since I’m a minimalist at heart – I rarely listen to Reich and Glass without wishing I could hear it really in tune);Â

4. the extreme chromaticism available (as a lover of late Romantic music like Max Reger, for whom there never seem to be half-steps small enough);Â

5. the pleasure of writing chord progressions never heard before (countering the deadening feeling in my equal-tempered music that there’s really nothing new I can do in the area of harmony); andÂ

6. the tendency toward hearing the actual sound in its totality, as opposed to the filtering out of acoustic beats we have to subconsciously perform to make equal tempered music make sense.Â

Don’t Shoot the Electronic Piano Player

The Op. 111 Club

I refuse to do those “playlist” things that tell you what I’m listening to lately, because 1. I go for long periods without listening to anything, and I’m entitled because I’ve already spent way too much of my life involved with other people’s music; 2. half of what I do listen to is for teaching reasons; 3. I often listen to pieces because I’m planning to steal ideas from them, so admitting it would sometimes be too revealing. But lately I’m listening over and over to a mammoth work that’s long fascinated me, Grand Hotel (1989)Â by Cornelis de Bondt. I found a score of it last year in Amsterdam at Donemus, and in fact, I envy the Dutch that they have such a helpful, friendly, professional institution as Donemus as a one-stop-shopping center for Dutch music. I hiked over to their spacious office (way off in an inconvenient corner of eastern Amsterdam) several times, and was welcome to listen to recordings and peruse scores for hours before buying anything. Imagine if the U.S. had a central place you could go to and look through scores by John Luther Adams, David Lang, Elodie Lauten, and almost any other American composer you could name – that’s what the Netherlands has. Although some of the younger Dutch composers have refrained from selling their scores through Donemus because, they told me, the place has gotten a reputation for representing the stodgier side of Dutch music. Given that they handle music by people as hip as Jacob ter Veldhuis, I couldn’t quite see the criticism myself, but I report what I was told. One easily imagines that if there were such a place in the U.S. it would get swamped by the officially approved orchestral New Romantic crowd of whom our elites are so dubiously proud, but Donemus struck me as admirably democratic in its absence of stylistic bias.

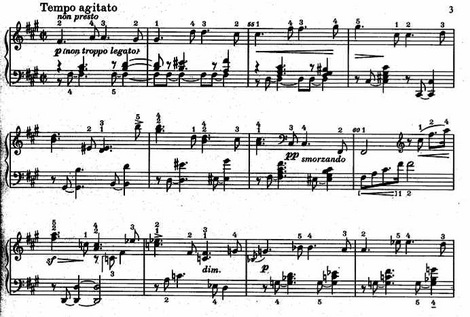

It’s a huge, sprawling, 37-minute essay, one of those complex pianistic virtuoso marathons mostly notated on three if not four staves, played in a frantic fury by Gerard Bouwhuis, and based on Beethoven’s Op. 111 Sonata. The opening diminished-seventh chords of that piece burst forth frequently, and many of the streams of falling 32nd-notes come from the concluding scale passages of Beethoven’s first movement. The longer (naturally) second movement is dotted with less obvious references to Beethoven’s tranquil Arioso theme, often simply sudden secondary dominant chords that hang quietly in the air. Key signatures – three flats, six sharps, five flats – run through the piece, although it more often sounds atonal than diatonic. The title, according to the liner notes, is a reference to the crumbling edifice of tonality, which certainly stands nobly, but in ruins, here. I’m told by one of his students that Cornelis de Bondt (b. 1953) teaches theory at the Hague Conservatory. I’ll upload an mp3 here for you, as is my wont, but only temporarily, for it’s a big file and I can’t spare the space forever.

Grand Hotel is a interesting contrast to Clarence Barlow’s Variazioni e un pianoforte meccanico, which is a theme and variations for live pianist and Disklavier based on the theme of Op. 111’s second movement. Barlow’s achievement is a stunning logical and technological feat, the computer grabbing data from Beethoven’s theme and composing its own cheery, sometimes almost humorous variations. Grand Hotel is far darker and more introspective, a kind of existential, manic-depressive drama featuring Op. 111’s elements in dozens of flashbacks, playing with sudden recognitions and buried shards of memory.Â

As documented here, though 95% of my musical influences are American, I’ve got my own long history of associations with Op. 111, a piece which haunts me almost as much as the Hammerklavier haunted Brahms. (Other European pieces deep in my compositional bloodstream include Mahler’s Sixth – which turned up in Custer and Sitting Bull – the adagio of Bruckner’s Eighth, Busoni’s Fantasia Contrappuntistica, Boulez’s Rituel, and everything Erik Satie wrote.) I’ve never directly quoted Op. 111 except in my Disklavier piece Petty Larceny, which consists entirely of quotations from the Beethoven sonatas, but my I’itoi Variations of 1985 was a kind of spiritual homage to it, and my two-movement piano concerto Sunken City mimicked Op. 111’s proportions and movement contrasts. In grad school, for Peter Gena’s class on the late Beethoven sonatas, I wrote a paper titled “Zen and Op. 111,” in which I analyzed the piece as a contrast between samsara and satori, between the earthly veil of illusions and the tranquility of Zen consciousness. My idea was that the first movement’s angry diminished sevenths chords represented a relentless drive to the final, sad resolution, while the arioso variations gradually defuse the polarity between tonic and dominant, creating an image of timelessness in which resolution becomes unnecessary:

(Years later, in a review of Pauline Oliveros, I described this same C-D-F-G sonority as a musical equivalent of the Yin-Yang symbol, a union of tonic and dominant with no thirds to specify major or minor.)

Obsessively quoting every historical thinker from Basho to Nietzsche and beyond, “Zen and Op. 111” was too embarrassingly immature to make public now, but at the time I was moved to write it by a book that I recently had the tremendous pleasure of rereading: R.H. Blyth’s Zen in English Literature. This is one of the books Cage read in the ’40s, and one I had discovered through his writings. Blyth was a British Japanese scholar who sat out World War II in Japan, and whose books on haiku elevated that genre to heightened visibility in the West. Zen in English Literature is an absolutely charming tome, a virtuoso display of astonishing erudition (which I tried ineffectively to imitate) in which he traces examples of Zen consciousness through Wordsworth, Dickens, Shakespeare, Keats, Blake, Pope, Donne, Milton, Chaucer, Cervantes (not English, but included anyway), and many others. Hamlet’s “There is nothing either good or bad but thinking makes it so” is the book’s continually recurring mantra, and he finds Zen in every perfectly self-forgetful artwork: “Art is frozen Zen.” No isolated example will do the book’s flavor justice, but for instance Blyth compares George Herbert’s

I made a posie, while the day ran by:

Here I will smell my remnant out, and tie

My life within this band,

But time did beckon to the flowers, and they

By noon most cunningly did steal away

And wither’d in my hand.

with Basho:

Leaves of the willow tree fall:

The master and I stand listening

To the sound of the bell.

as a type of self-identification with nature. Zen is Blyth’s poetic criterion, in fact, and for want of it he damns Coleridge as merely a sentimental pantheist.

Zen in English Literature is the liveliest and most enlightening introduction to Zen for a Westerner I’ve ever found; it’s long out of print, but I located a used copy from Amazon, and enjoyed it all over again. By Blyth’s way of thinking, Zen could be found in much (or any) great music, but there’s something special about the second movement of Op. 111 and its gradual dissolution of 19th-century goal-directed syntax. In fact, one could impose the two movements of Op. 111 as a metaphor on modernism versus minimalism, or perhaps postclassical music, in general: anxiety, portentousness, climax-orientation, and ambition versus calm, intuition, flatness, and paradoxical nonsequitur. The karma-riddled first movement is entirely classical, but the Arioso lays out a postclassical harmonic agenda many decades before the fact. Perhaps that’s why the piece has never relaxed its hold on me, and every musical work that makes reference to it demands my attention.

Daily Challenge

[UPDATE: Anwer below] Don’t you wish your doctoral music exams could have gone on forever? I know I do. And here, just to relive a little of the thrill, is a small test reminiscent of same. If you can guess the composer’s name, you and I have a lot to talk about, but failing that, guess 1. the date of composition, and 2. the date of the composer’s birth. Here’s an mp3 of the passage so you don’t have to drag your computer to the piano.

Bleak Inheritance

I wrote an article on William Schuman for Symphony magazine, which I’ll give you the details on presently. I couldn’t really spare the time, but chances to write about Schuman are rare, and I love his music too much to have resisted. I gather that being a huge Schuman fan puts me in somewhat of a minority (what else is new?). There is a prejudice abroad that Schuman’s composing career was only propped up by his powerful position as President of first Juilliard and then Lincoln Center. Don’t you believe it.

I met Schuman once. He had some piece played in Chicago in 1986, and I reviewed him by phone for the Chicago Reader, then introduced myself at the performance. I wish I had had the chutzpah to insist on getting to know him. I told him that at home, beneath my bed, was a box of compositions I wrote in high school, most of them attempts to plagiarize the bleak opening atmosphere of his Eighth Symphony. In perfect crusty-old-sea-captain character he growled, “Surely you can do better than that!” Here’s the passage in question, a reiterating series of succulently grim major-minor triads leading to a long, angularly wandering horn solo:

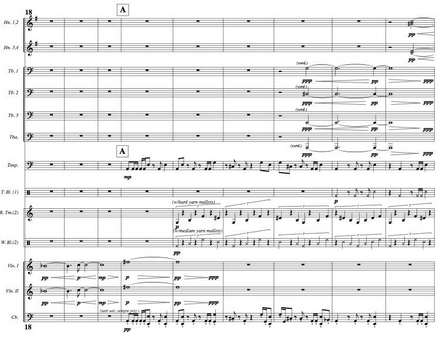

I know it’s fuzzy, but try to look at those two harps and the piano, with tubular bells playing both thirds of the triad and a grace-note in the glockenspiel. Delicious. There are few passages in the orchestral literature I love so dearly. It’s desolate, haunted, almost motionless, yet palpably not despairing; there’s a latent energy to the rhythm and even the subtly shifting voice-leading that somehow forecasts the sardonic fireworks that will come in the third movement. It’s as Americanly tragic (sorry, “tragically American” just won’t do) as The Grapes of Wrath – a novel that coming events may compel us all to reread. I love Schuman’s Third, Fifth, Sixth, and Seventh Symphonies too, and his New England Triptych, and I played his less impressive piano piece Voyage which had a little impact on my piano writing, but the Eighth is the one I kept trying to duplicate.

My guilty secret is that before I discovered Cage at 15, I had already lost my creative vriginity to the Harris Third, the Schuman Eighth, and the Bernstein Second (gang-banged, as it were). My high school composing style slithered around among Schuman, Harris, Ruggles, Copland, Bernstein, and – more consciously but a little more distantly as well – Ives. Had I not then fallen in with the Cage crowd, I suppose I’d be writing symphonies today. And I still suspect that my personal take on minimalism, heard through glacially moving microtones, minor-triad obsessions, and even my fetish for the 11/9 interval (347 cents) that’s halfway between major and minor, was conditioned by the spellbinding effect Schuman’s gloomy chords had on me at a tender age.

I’ll put up a first-movement mp3 here temporarily, but hopefully everyone already knows this piece.