Kyle, please keep blogging regularly. Your metametrics posts literally changed my life when I was starting my undergrad. I am now waiting to hear from grad schools after sending them applications and writing samples covered in the names Branca, Chatham, and Gordon.

This comment to my last post sticks acupuncture-like into my reasons for blogging or not blogging, my attitude about teaching, and a lot of other aspects of my life. I never press minimalism, postminimalism, or totalism on my students. Some of my composition students are very ambitious, and want to go to grad school. I know that a knowledge of, let alone strong interest in, Partch, Branca, Diamanda Galas, Glass, Young, Mikel Rouse, Ashley, Art Jarvinen, and all these other nutcases I’m fascinated by – what I consider the great music of my time – will not be assets to an academic composing career. I know my students should be able to analyze Stravinsky, Stockhausen, Nancarrow, Webern, and what academia considers the canon. I feel guilty even trying to interest them in the music I most believe in, because while it might excite them artistically, I know that the best composition careers go not to the most exciting composers, but to those who follow the academic/classical script. Of course, if they come to me interested in that music, I eagerly supply them with all they want. I have two file cabinets bursting with unpublished and self-published scores of “my kind of music.” A handful of students, mostly grad students from other schools, have come to me precisely for that, but not one has ever taken advantage of more than a fourth of what I could offer in that area. Consider:

A few years ago, a few students asked me for a tutorial on minimalism, which I happily provided. One of my colleagues, finding out, became incensed with me, and shouted, “See? You’re influencing them! You’re influencing them!” – as though I weren’t supposed to do that. But in fact, the student who led the tutorial request was the son of a woman whose favorite composer was Steve Reich. I try not to influence my students toward my own aesthetic direction because I know it won’t help them career-wise.

I apply frequently for senior composition, theory, and history jobs, but I almost never get interviewed. My publication record is superb, I have excellent references from friends who chair departments at other schools, and my student satisfaction ratings are very high. I can only conclude that it is the content of my publications, my academically incorrect aesthetic position, that scares away other departments from considering me. Sure, I directed an international conference on minimalism – but minimalism remains a dirty word in academia. And why would I want to burden any of my students with the same disadvantages under which I labor?

And yet, aside from writing my music, which I secretly think is very good – one of my guilty pleasures – I think the most useful and fulfilling role I could play would be as a distribution channel for the commercially and academically unviable music I love. Nothing would give me greater pleasure than for someone to provide me with the money and wherewithal to scan those files cabinet’s worth of scores to create a Free Internet Library of Downtown Music, where students who have an interest in it, like Patrick above, could feast their eyes and ears on all this alternative music. But how could I do that in a world in which copyright difficulties won’t even allow me to write, “Creep into the vagina of a living,” etc., and in which even the word “Downtown” raises the hackles of the vast majority of musicians? As long as there was a Downtown scene in New York that provided an alternative career path for composers who don’t write the kind of music orchestras and those oh-so-precious classical musicians will program, there was a reason to continue this work. Incorrigible heretic that I am, I believe that there still is a Downtown scene: you’ll find it in organizations like Anti-Social Music and New Amsterdam Records, among others, in which young composers take the distribution and performance of their music into their own hands, which is virtually a definition of Downtown. But even the young composers involved today seem uninterested and unknowledgeable about the music I’ve spent my life immersed in. Downtown New York has always been that way: each new crowd comes in, and has little feeling of connection with the dominant crowd that preceded it. Bang on a Can shrugged off free improv, just as Zorn shrugged off minimalism. And I find myself working night and day for a musical generation that has been shrugged off Downtown, and of course doesn’t exist for academia or the classical music organizations.

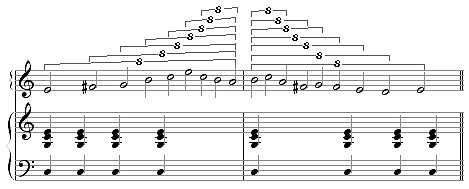

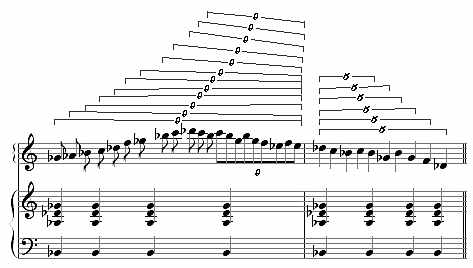

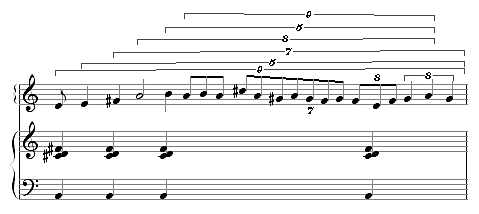

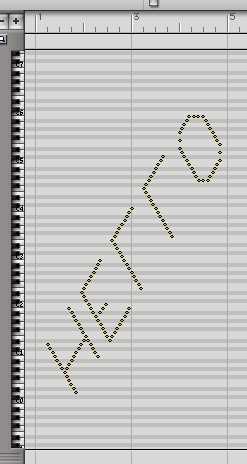

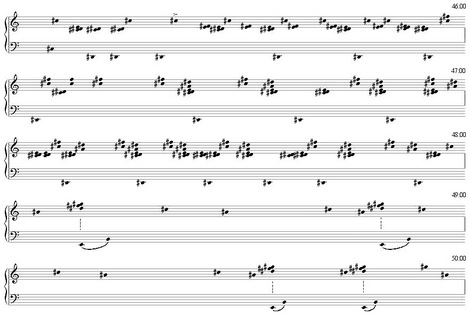

Frankly, I’m 54, and I’m dog-tired of working as hard as I’ve worked all my life. But more accurately, I think I would be happy to continue doing the work if considerably more reward and acceptance came as a result. I’ve been on a big scanning spree during this winter break – mostly of scores I plan to teach in upcoming semesters, and largely because I save a ton of trees by projecting the music on a screen in class rather than Xeroxing it. But I also keep scanning scores of the postminimalist music I like to lecture on, and one score I scanned this week was Carolyn Yarnell’s The Same Sky, which I think is one of the most fantastic keyboard works anyone’s written in the last 20 years. I’ve made it available here before on mp3, and I do so again here, also with part of the score, which I think Carolyn will be rather complimented than annoyed by:

Kathleen Supové is the pianist. [UPDATE: By the way, notice that the sole dynamic marking is the mf at the beginning. The second dynamic marking is a pp on page 8. Welcome to postminimalism.] I hope to get time to analyze the piece sometime, so I’ll have more to say about it. What would be even more gratifying would be if I inspired some student to analyze it and send me the paper. I wish I could direct this activity specifically toward the younger musicians who would find it interesting, and not toward those who reflexively find it Not Serious. I rarely get to feel that such efforts are worth the amount of work I put into them. I seem more often penalized for my expertise than rewarded for it. But to the extent that this blog has a purpose, this is where I see it. It is not a very efficient medium, but it is almost the only medium I have, aside from the laborious producing of books.

As always, the number one and inviolable rule of this blog is, if you don’t like the music, I don’t want to hear from you, and will not publish your response. It would be unfair to Carolyn to get criticized on the internet as a result of my momentary appropriation of her work. If you don’t like the music, ask yourself why you think it’s important for the world to know you don’t. What good does an expression of your disapproval serve? None of the composers I champion is getting rich off their efforts; most of them are eking out extremely slim careers. They and I wield no power over others that needs be combatted. By criticizing, you merely add your voice to an enormously well-supported status quo that will thrive nicely without your reinforcement.

In other words, if I can figure out how to get this blog to more efficiently serve the grandest purpose I can imagine for it, without wasting energy on all the other stuff that serves no purpose at all (like defending the music and my terminology), I will gladly keep doing that. And if I figure out some other medium that would be more productive and rewarding, I will switch to that – even if it turns out to be something less public.