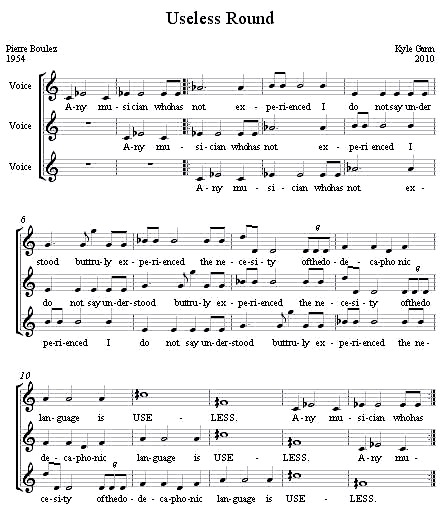

Four days into the summer, I’ve completed my first piece. Larry Polansky publishes an expanding book of rounds, and for years he’s been bugging me to write one, so I finally did. Dodecaphonically. [UPDATE: Larry’s put a better copy on the web here, and you can also see a lot of the other rounds in his collection.] [MIDI piano version here.]

Search Results for: www.kylegann.com

Music in the Prison’s Shadow

I still have a couple of full days this week, but the bulk of my school work came to an abrupt halt last night, giving me today my first chance to breathe in weeks. Except for their orchestral performances this Friday, my seniors are pretty much packed off into the world to start figuring out, come Sunday, what they’re going to do with their lives.Â

Snake Dance No. 3Â (11:29)

Composure  (13:43)

The Disappearance of All Holy Things (11:38)

I Slept and Dreamed that Life Was Beauty (1:45)

In the Busy Streets (0:43)

Dinner with a Genius

Every 29 Years, Saturn

BELGRADE – Saturn is sextiling my Sun and ascendant from my tenth house, if you know what that means. What it means is, I’m kind of difficult to escape at the moment. The always impressive Frank Oteri has a wonderful interview up with me today on New Music Box, in honor of my new book and two recent CDs. I always knew Frank was sort of ridiculously brilliant, but I didn’t realize how brilliant until he started digging into my music and making me see it from a different angle than I’d ever seen it before. In addition there’s another interview with me by John Ruscher on BOMB magazine about my Cage book. There’s also a nice review of my Cage book by Robert Birnbaum at The Morning News. I’m all over the internet today. This, too, shall pass.

Vuk Kulenovic: Virginal (he lives in Boston now; some of the best Serbian composers escaped during the ’90s)

Countries with Sexier Composers than Us

OK, kids, gather around, it’s time for Uncle Kyle to continue your education in Serbian music. I’ve already told you about Ljubica Maric (1909-2003), who was the country’s leading modernist composer of the early 20th century, and the only woman to occupy that position in her country’s culture. Nor will I repeat what I said there about Stevan Stojanovic Mokranjac (1856-1914), the country’s leading musical patriarch and composer of traditional choral music.

A Man Grown Silent in the Praise of God

The Dessoff Choir’s March 6 performance of my Transcendental Sonnets, based on poems by the Transcendentalist poet Jones Very and conducted by James Bagwell, is now up on my web site:

Floating in Free Pitch Space

Microtonal theorist Timothy Johnson, of whose theoretical skills and even more his work ethic I stand in awe, has sent me the MIDI file he made of the first 30 measures of the final movement of Ben Johnston’s Seventh String Quartet, of which I wrote in my last post. At 2:41, this represents about a sixth of the third movement, which must total 16 minutes. I can’t listen to it enough: exotic consonances floating in a totally free, gridless pitch space. This is truly the music of the distant future. He made the file with piano sounds, since MIDI string sounds are vulgarly inadequate, so you’ll have to imagine this played by a string quartet. I wish I thought I would live long enough to write music like this, but I’m too pragmatic, not visionary enough. The score is published by Smith Publications, if you’re interested in studying it yourself.

The Mount Everest of String Quartets

One of the best things the Microtonal Weekend at Wright State University did for me was initiate me into familiarity with Ben Johnston’s Seventh String Quartet. Written in 1984, the piece has never been played. It has a reputation as being the most difficult string quartet ever written. Timothy Ernest Johnson of Roosevelt U. gave a paper analyzing the third movement (his doctoral dissertation is on the entire work and also Toby Twining’s Chrysalid Requiem), and for the first time I learned exactly wherein that difficulty consists.

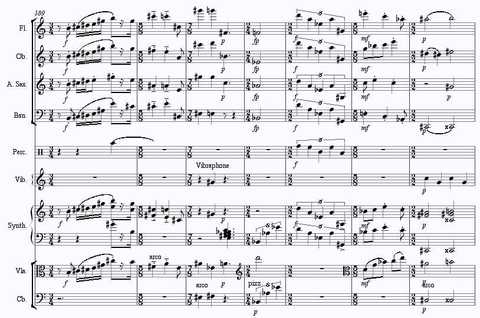

If you know much about Ben’s Third Quartet, you know it works its way measure by measure through a 53-note microtonal scale. The finale of the Seventh is built on a similar plan, but the structural tone row consists of 176 pitches – all different, 176 pitches within one octave, heard in the viola on each successive downbeat. Many other notes are heard in the other instruments whose harmonies link each note to the next, and Tim tells me that altogether there are more than 1200 discrete pitches in the movement – more than one per cent, five times as many as most people can perceive. That does sound a little tricky to play. Tim demonstrated how the players are supposed to proceed from the opening C to the subsequent D7bv-, a pitch ratio of 896/891. The violist is tasked to move upward from this C and come back down on a pitch 9.7 cents higher – just under one tenth of a half-step – than she started on. At the downbeat of the next measure, the violist lands on Dbb–, pitch ratio 2048/2025 – another ten cents higher. And so on for another 175 measures until the viola ends up traversing the octave and ends at C again. A good half of Tim’s paper was spent talking us through the performance challenges of the first two measures. Between the first and second downbeats (pictured below), the quartet is supposed to tune the F to the C and the Bb- to the F, the Ab- and Eb- in the cello to the Bb- in the first violin and the 7th harmonic G7b- above that, and find the 11th subharmonic below G7b-, and, voilà , viola, you’re on D7bv-. It’s just 4/3 x 4/3 x 2/3 x 2/3 x 7/4 x 8/11, and bob’s your uncle, there’s your 896/891. It can’t be too much more difficult than four people traversing a 177-meter tightrope together without holding hands, or manually flying four biplanes in parallel in and out of the mountains through a dense fog. I mean, it’s not like they’re calculating all this while playing an accelerating tempo canon, for god’s sake.

The tempo is slow and the rhythms relatively simple, though there are serialized aspects to the rhythm and meter, correlated to pitch differences in the row. Ben recalled that his original proportional scheme would have made the piece last 48 years. Tim Johnson was applauded by others in the audience who had tried to untie this Gordion’s knot and failed; he’s been working on it for five years, and developed a set of computer programs to help him process the cascades of pitches and ratios. Best of all, he played a MIDI version of the movement’s opening 30 measures. It was, indeed, breath-taking: consonances slid into slightly new consonances in recurring patterns, but with no sense of a background fixed pitch grid whatever. [UPDATE: Tim kindly sent me the MIDI file to post, so listen for yourself. It’s done with piano sounds, so imagine a string quartet playing it.] I think I can truly claim that never, in the history of the world’s music, has such deeply-layered complexity sounded so translucent.

I have bowed low before many an unfathomable musical achievement, but before this one

I absolutely prostrate myself. Imagine Ben writing in pencil, in 1984, a string quartet that would later require multiple computer programs to unravel again! How can a mere MIDI-piano version of 30 measures of a yet-unperformed work change your ideas of what music can achieve? Boulez and Stockhausen, you are hereby blown out of the water, your musical understanding has been revealed as merely rudimentary by this Burj Khalifa of sonic conceptualization. The Kepler Quartet, from whom violinist Eric Segnitz was present for the conference, is expected to record the piece for their series of Ben’s complete quartets on New World. Good. Luck.

Thankfully, due to another analysis paper by Daniel Huey of U. Mass., we also got to hear Ben’s Tenth Quartet (1995), which I’d also never heard before. This is a considerably simpler piece, and in fact the final movement is a theme and variations on the tune “Danny Boy,” which isn’t revealed until the very end. The harmonies are tight, fluid, elegantly voice-led, and creamy. The Kepler’s next CD (SQs 1, 5, and 10) comes out in October, and I guarantee you’ll enjoy the 10th. Its simplicity-within-complexity and complexity-within-simplicity will gratify biases all across the spectrum, and with its resonantly pure yet exotic chords it just sounds great.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

In other news drawn from the colloquium (which was astonishingly dense with relevant news, considering it flew by in a mere 29 hours), the other honoree was the late piano tuner Owen Jorgensen, who wrote the massive book on the history of keyboard tuning manuals in English, Tuning (I won’t take the time to look up its voluminous subtitle). Momilani Ramstrum of Mesa College talked about Jorgensen’s life and said that he rather embarrassed Michigan State as their staff piano tuner by becoming more of a celebrity than most of the faculty, so they made him a full professor and let him teach piano tuning. On the other hand, registered piano technician Fred Sturm of UNM gave a polite but exhaustive tirade against Jorgensen’s influence, charging that since he limited himself to British sources, and Britain was a few decades behind the Continent on tuning issues, he’s created a misleading picture of tuning history that others (myself included) are now quoting uncritically. This sounds perfectly plausible, and doesn’t interfere with the pleasure I get from Jorgensen’s passionate speculations about the relation of composing to tuning. However, it turns out there’s a new tome in English now by Patrizio Barbieri simply called Enharmonic which contains a more accurate and voluminous documentation of the history of tuning all across Europe and across the centuries. You can obtain it, as I soon will, at Barbieri’s web site, and I will expect you all to have read it before I blog on the subject again. Frank Cox passed around a copy, and it looks massively impressive.

Microtonal guitarist John Schneider, slapping an endless series of interchangeable fretboards on his axe, started us out with a 100-minute introduction to the history of tuning that hit every salient point, made every principle clear, demonstrated every nuance beautifully on the guitar, and was thoroughly delightful and entertaining. If you ever need a lecturer on this topic, he’s your man. I couldn’t have done it. In five hours or 15 weeks I can make a lot of good points about tuning, but he’s distilled it into a compact traveling road show. And John Fonville led a group of students though a continuum of perfectly tuned tone clusters in Partchian otonalities and utonalities whose beauty we could all appreciate. He’s looking to take that to various schools as well. If I can ever get these guys up to Bard, I will jump at the opportunity.

Ben Johnston offered some lovely reminiscences on his education and career, which microtonal composer Aaron Hunt quotes on his blog, so I refer you there. Aaron gave his own colorful presentation on the microtonal instruments he’s selling through his HÏ€ company, to whose web site http://www.h-pi.com/index.html I additionally direct you. Thanks to Franklin Cox and Wright State University for a colloquium that delivered more punch per presentation than just about any academic event I’ve

ever attended.

I’ll only add that, in addition to what Aaron quotes, Ben Johnston and I shared a moment I’ll never forget. After my address in his honor, he hugged me and said, “Thank you, thank you, thank you.” I replied, “Ohhhh, thank you.” And he looked me right in the eye with the old twinkle I remember from decades past, and growled cheerfully: “You’re welcome!” False modesty on his part would have been devastating at such a moment. For him to acknowledge some small honor I could pay him was pleasant, but for him to acknowledge what he’d done for me - spinning my life off in a direction I hadn’t anticipated, yet one that expressed perfectly what I needed to do – was ten thousand times more fulfilling. If decades hence any student ever thanks me for my impact on his or her life, I’ll remember how important the words “You’re welcome” can be.

Regarding Ben

You can’t make a living giving keynote addresses, but through repetition you can become proficient enough at them to take them in stride. Here’s my keynote address honoring my teacher Ben Johnston, for the Microtonal Weekend at Wright State University, organized by composer and microtonal cellist Franklin Cox:

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Charles Ives once fantasized about “some century to come, when the school children will

whistle popular tunes in quarter-tones.” It has long seemed to me that when I hear people whistling popular tunes, quarter-tones are indeed often involved, but I think what Ives had in mind was that the popular tunes would be written in intentional quarter-tones. I don’t think this is likely to happen in my lifetime, but I do think that, thanks to several other important composers, Ben Johnston chief among them, the time may soon come when musicians feel free to hit the occasional seventh or even eleventh harmonic in their music, vernacular and otherwise.

I love listening to quarter-tone and sixth-tone music. It instantly puts you into a world in which our habitual musical categories fall apart. You lose the moorings that every musician gets trained into, and the rational part of your brain, the part that can analyze and identify what we hear, gets

short-circuited, and has to surrender to pure sonic experience. However, in general I find that, in a long quarter-tone piece, the delicious strangeness becomes uniform, and settles into a monochrome grayness. It’s like being dropped on an unfamiliar planet: the initial thrill of exoticness gives way to relentless disorientation. The quarter-tone musical universe is too strange, and difficult to get used to. In this world the composer, faced with all those new available pitches – though of course there are sensitive exceptions in the music of Wyschnegradsky, Eaton, and others – the composer tends to exclude the familiar, and thus minimize contrast.

This is the principle according to which Ben Johnston’s microtonal music – and not only his music, but his entire approach to music – has always seemed stronger to me, more inviting, and more enduring in its appeal. Its starting point is the harmonies that have been used in music for hundreds of years. From that point it grows outward into more exotic harmonics, which we learn by hearing, as the fineness of our pitch discrimination increases, to incorporate into what we are already familiar with. Theoretically speaking, Ben, like Harry Partch before him, does not take a sudden left turn from 1920, as the quarter-tone composers did, but goes back to the tuning arguments of the 16th century and starts over. For the Renaissance musician, a sharp multiplied a musical frequency by the fraction 25/24 – and so does it in Ben’s music. In Renaissance music, major triads represented a set of tones vibrating at ratios of 4, 5, and 6 – and so they do for Ben. The C major scale represented the center of the musical universe, and a take-off point for more exotic phenomena – and so it does for Ben.

What happened in the 16th century, limiting our musical resources for the next 300 years, is that a decision was made to exclude the number 7, and all larger prime numbers, from our theoretical vocabulary. Under English influence in the 15th century during Henry V’s war of occupation, French

theorists were convinced to expand their tuning arsenal from 2 and 3, the octave and perfect fifth, to 5, which gave them a consonant major third as well. But when they came to the number 7, the seventh harmonic, despite the advocacy of certain intelligentsia like Nicola Vicentino and the famous mathematician Marin Mersenne, the theorists balked. The victorious Zarlino insisted on the infamous senario, the numbers 1 through 6, as the basis of musical consonance. He argued by analogy on the grounds that there are six directions (up, down, right, left, forward, and backward), six zodiac signs (as long as you count only the ones visible above the horizon), six visible planetary bodies (as long

as you don’t count the Sun), and so on. That there are seven days of the week, let alone 13 full moons a year and a 19-year cycle of sun and moon phases, he seems to have conveniently overlooked. The decision was cultural, political, and even racist, besides being sixist. The hindus and arabs used prime tuning numbers larger than 5, and the good Catholics of 16th-century Italy were not going to follow the path of the heathens. And so for over 300 years, Europe and then America sweated by on

12 impoverished pitches only designed for the playing of simple triads.

This was the decision that Harry Partch set out to undo in 1928 when he burned his early music in a pot-bellied stove in New Orleans and started over with the 7th and 11th harmonics. It was Ben Johnston’s contribution to create a notation in which to think musically with the 7th, 11th,

and even higher harmonics, and to pursue an expansion of acoustic-instrument performance practice with those harmonics.

The fact is probably already familiar to this audience, but I will recount it ritualistically, that in Ben’s most famous work, his Fourth String Quartet based on the common folk tune “Amazing Grace,” he gave us a vivid template in how to expand music through the harmonic series. The piece, as you all know, is a set of variations. The first statement of the theme uses only the primitive pentatonic scale of the French 14th century, based on ratios of 2 and 3 – also presumed to be the scale of rustic folk fiddling. The first variation adds in the pure thirds added by the fifth harmonic. The fourth variation adds so-called “blues” notes of the seventh harmonic, and the fifth brings in the seventh subharmonic, until at the end the music traverses a symmetrical 23-tone scale firmly anchored in the key of G- (that’s G minus, not G minor). At the very end, pitches are again subtracted precipitously, and the

music ends in a simple and familiar final cadence.

At the same time, of course, Ben opens the piece with the beat divided only into

simple 8th-notes and triplets. When he adds in the fifth harmonic, he also adds quintuplets to the rhythm, and as he folds in 7th harmonics he adds in septuplets, in systems so intricate that one variation is based on a structural polyrhythm of 35 against 36, which also happens to be the pitch ratio difference between a 7th harmonic and a regular Renaissance-era minor seventh. In this mirroring of the same numbers in both harmony and rhythm, Ben achieves in the work a beautiful manifestation of the vision Henry Cowell sketched out imperfectly in his 1930 book New Musical Resources. In that book Cowell theorized that the languages of pitch and rhythm could be developed isomorphically rather

than separately, as had been traditional. (Tomes have been written about Ben’s microtonal usage, but his role as a rhythmic pioneer, I think, has never been sufficiently acknowledged.)

Had Ben never written another work, this piece, the Fourth Quartet, would have been a sufficient blueprint for how music could expand its resources magnificently in the 21st and 22nd centuries. It is an ontogeny on which a phylogeny could be fashioned. All of my own music has taken place, rhythmically

and harmonically (even my non-microtonal music), within the expanded universe opened up by that piece – not simply because I studied composition with Ben, but because he solved, notationally, pragmatically, and creatively, the impasse posed by the premature moratorium on prime numbers higher than 5 adopted in the late Renaissance. (One could say something similar about Harry Partch, whose own rhythmic explorations have also been too little noted, but Ben solved it for those of us whose carpentry skills are less than impressive.)

I first met Ben around 1976 when I was a student at Oberlin, but I didn’t get to know him until 1983. At a wonderful concert of his music in Chicago, I went up to him and asked if I could study with him. I had already finished my doctorate, but I had never studied regularly with a very famous composer, so I asked to drive downstate to Urbana every now and then for a lesson with him. It turned out that he was also traveling to Chicago frequently to attend a Zen temple, and so sometimes I would meet him there instead, and eventually I started attending the Zen services with him before our lesson. What I didn’t tell him was what I was saying to myself: that although I loved his music, I wasn’t going to get involved in this microtonality business, because it was too much work for too little payoff.

Ben never proselytized for microtonality. But in my very first lesson, he made a casual comment about how nice one of my harmonies would sound if you tuned it properly, and he reeled off the fractions. I had been the star math student of my high school, and merely realizing that I possessed what it would take to enter Ben’s new harmonic world presented an attraction from which I was helpless to draw back. He didn’t need to encourage or convince me. I suddenly realized at that moment that a door had just shut behind me, and there was no return. I wrote very little music in my four years with Ben, but I filled entire notebooks with pages and pages of fractions. Not until 1991 did I finally manage to write a piece that was completely microtonal in conception, that couldn’t be meaningfully approximated on the piano. I figure Ben delayed my composing career by five years. But he bestowed upon me the heady pleasure of being able to compose harmonic progressions that had never been heard

before.

I can’t guess what might have happened if I had studied microtones with John Eaton or Easley Blackwood instead, but I do know that Ben’s approach made intuitive sense to me because it started with the familiar and moved out gradually and organically into the exotic – sometimes in a calculated and

dramatic fashion. I remember when I first started driving to Urbana that he would first bring in and enthusiastically play me the music he was working on. He’d start playing – I particularly remember this happening with his piece for trumpet and piano The Demon Lover’s Doubles – and the music would seem rather normal. A couple of minutes later, I’d start thinking, “Gee, Ben’s piano is badly out of tune, you’d think he’d call a piano tuner.” And then by the end of the piece his piano would have become miraculously in tune again. I was stumped. I didn’t understand tuning enough at the time to realize what was happening; I know now that his piano sounded more and more out of tune the further he strayed from the central key it was tuned to.

I want to replicate for you an experience Ben gave me once by playing you The Demon Lover’s Doubles. I used to have a recording of this on cassette, but unfortunately it’s been misplaced over the years, and so I’ve made a MIDI version whose quality I apologize for, but that will at least give an accurate representation of the tuning.

This is a subversive piece. It draws you into a false sense of security and then suddenly [at 2:28 out of 4:10] throws you into an abyss in which you doubt your own senses – and it does so with just a simple 12-pitch scale tuned to one key. Looking back, I’m embarrassed that at 28 I was too ignorant to fully get the joke. I’m also glad that I was forced to make a MIDI version, because it wasn’t until I added the dynamics that I realized how clever the conception is. The middle variation is loud and bangy, and then the music turns mysteriously quiet just as the last four disorienting pitches get

added in. The whole scale is tuned to the key of D, but those last four pitches – 15/14, 11/9, 15/11, and 14/9, if you’re keeping track – load in two more unexpected dimensions of the harmonic series. You’ve been riding along comfortably with 2, 3, and 5, just as your family had done for generations, and suddenly you get a visit from 7 and 11. This simple-sounding world is not what you thought. It contains a portal to the demonic world – a world that studying with Ben soon made me eager to enter. And the music raises your sense threshold with its grand loudness before suddenly sinking down to a pianissimo level at which not only are you hearing something really weird and unexpected, but you’re not quite sure what you’re hearing because it’s suddenly so soft. It’s one of the great sucker punches in music. And in 1985 I was a great sucker

I later found a more subtle example of Ben’s pitch magic in his Suite for Microtonal Piano of 1977. In this piece the piano is tuned entirely to overtones of C, specifically the 1st, 3rd, 5th,

7th, 9th, 11th, 13th, 15th, 17th, 19th, 21st, and 27th harmonics. According to one of the prevailing misconceptions about just intonation, this should mean that only music in the key of C major should be

playable in this scale. However, Ben couches the second movement in the key of D, and the fourth in the key of E with an interlude in G. Each of these movements sounds perfectly at home in its tonic key, yet each offers a different set of intervals to the tonic note, and thus a different repertoire of peripheral harmonies. In effect, Ben has invented the possibility of treating an unequal 12-pitch scale as a mode, with different potentials on each tonic. The scale contains only five perfect

fifths, and it is on these fifths that Ben grounds his basic harmonies. Exotic intervals available on D that aren’t available on C include the ratios 19/18, 11/9, 13/9, and 17/9. The range of chords on these pitches, which would sound jazzy but rather tame on a conventionally tuned piano, offer a vastly expanded range of consonance and dissonance of which Ben takes full advantage. The climactic chord progression ranges from a chord whose ratios would have to be analyzed as 27:32:44:52:72 down to one that is simple 2:3:4:6. This range provides an entirely new dimension between extremes of consonance and dissonance unknown in previous keyboard music. In 12-tone equal temperament, dissonance depends mostly on seconds and sevenths; on Ben’s piano, one has not only those but strangely tuned thirds and sixths, a completely different flavor of dissonance – or as Harry Partch memorably put it: “an entirely different serving of tapioca.

I’d now like to contextualize all this with reference to Ben’s quiet, little noted, but persuasive contribution as a music theorist. Though not as noisy or controversial about it as some other composers later were (notably one of his more outspoken students), he was probably, or seems so in retrospect, the first to publicly criticize serialism on theoretical grounds, and not from a conservative position, but from a radical one – not because it went too far, but because it didn’t go far enough. Much later, Fred Lerdahl would write a paper about “cognitive constraints” in which he demonstrated that our brains are not wired to process permutations as musical phenomena; years later, George Rochberg would publicly stop writing 12-tone music and scandalize his colleagues by returning to Romanticism; soon, the first minimalists would return to writing in a diatonic scale. But before all of these, as early as 1959, Ben was writing about the limited intelligibility offered by an interval scale in a 12-tone context. In 1962 he drew on then-recent findings in experimental psychology to draw a distinction between nominal, ordinal, interval, and ratio scales:

A nominal scale is a collection of equivalent and interchangeable items. An ordinal scale is a collection which is rank-ordered in terms of some attribute. An interval scale is a rank-ordered collection in which the intervals of difference between items are equal. A ratio scale is a rank-ordered collection in which the items are related by exact ratios…. Each of these scales includes all of the measurement possibilities of its predecessors, plus one more.[1]

The major and minor scales of European tonality are ratio scales, because it is possible to judge the ratio of each frequency to the tonic. Twelve-tone method gives us only an interval scale, because all we can hang on to are a group of intervals whose size differences are uniform. It is because the methodology of 12-tone music allowed only for interval scales and not ratio scales that Ben was able to announce that, “in an important and basic way serialism is… a less sophisticated technique than tonal organization.”[2]

As long as the basis of music was triadic, he wrote, the out-of-tuneness of

12-tone equal temperament was of negligible importance, but in the long run the

system offered an inadequate conceptual model for expansion. “When many of

these usages become outmoded,” he wrote,

and a search for new principles of musical organization

begins, as has happened in the 20th century, the one-sided model

provided by equal temperament becomes a serious but largely unrecognized

limitation. When musical organization based upon a linear (interval) scale

replaces that based upon a ratio scale, there is a net loss in audible

intelligibility.[3]

Note, however, that unlike other

composers who identified a fatal flaw in the 12-tone language, Ben didn’t stop

writing in it. I once asked him why, since he was a just intonationist, he

continued to write 12-tone music, and he answered, “Well, I had learned all

that technique, and I didn’t want it to go to waste.” In his 12-tone music,

though, he applied his own critique as a reform. In his remarkable String

Quartet No. 6, the first hexachord of the row is a harmonic series on D, and

the second is an undertone series on D#. This means that all 12 notes of the

row are not equal in weight, because one note in each half of the row is the

fundamental from which the other five pitches are derived. The pitch matrix for

this row contains 63 different pitches within the octave. The piece rocks back

and forth between overtone series’ and undertone series’, in a thoroughly

tonalized 12-tone technique.

Ben’s point of view, reaching back

into the Renaissance and breaking with some of his immediate contemporaries,

brought him to take stands that were both radical and conservative. As he wrote

in 1976:

Feeling that the harmonic mode of pitch perception is far too important a resource of human capability for it to be allowed to fall into disuse, I have set about to reestablish ratio scale usage in pitch organization. This has entailed a number of radical means (large numbers of microtones, for instance, entailing new performance techniques, especially for wind players), some strongly conservative practices such as the resumption of a sharp awareness of degrees of consonance and dissonance as a major musical parameter (which amounts to revoking Schoenberg’s much-touted “emancipation of the dissonance”), and even some radical reactionary attitudes, for example, the

rejection of the idea that noise, “randomness,” and ultracomplex pitch are the primary frontiers for avant-garde exploration.[4]

I’d like to add to Ben’s critique the complementary formulation expressed by George Rochberg, another excellent 12-tone composer who decided there was something wrong with the idiom. According to Rochberg, every new era in music history took the previous era’s practice as a basis and added to it. Not until the atonal period ushered in in the 1930s, he wrote, did musicians begin to prohibit use of the resources that had served previous composers. The 12-tone style mandated an avoidance of octaves, an avoidance of triadic points of tonality, an avoidance of evident regularity. And as Rochberg wrote, an aesthetic based on negation and prohibitions cannot serve the human race for long. As Ben put it,

It is clearly necessary to generalize the concept of tonality if it is not to be abandoned altogether. The solution should have the characteristic of including traditional methods within it, as special, limited cases.[5]

I don’t know how, or to what extent, this attitude seeped into my mind through Ben, or how much it simply made irrefutable common sense. But I do know that in 1983, around the time I started studying with Ben, I overcame a deeply ingrained, college-implanted artificial squeamishness, and started composing in triads. It has seemed increasingly obvious to me that we can’t achieve our greatest potentials in music without using all the effective musical devices that served composers in the past, as well as adding those innovations which are unique to us. Serendipitously, Ben turned out to be the

perfect mentor, not only to allow that large thought to settle, but to stretch it out in both directions, past and future, to make it seem infinitely commodious and inexhaustible.

There are many, many different approaches to microtonality. All of them are valid.

Each one suits a different set of creative needs. In the long run, some will turn out to have been more fertile than others. For me, it is this capacity of Ben’s approach to reach deeply into the past, and yet remain open-ended with regard to the future that makes it the most rewarding. It satisfies my need for history, flatters my limited mathematical talents, gives me adequate means for organizing only five pitches to the octave or 500 as I need at the moment, and offers me an infinity of potential organizations, absorbing even 12-tone music itself into the ongoing evolution of tonality. I’ve always loved the words that Ben wrote in his original liner notes to the “Amazing Grace” quartet. Because

that piece is so well known we forget that it is part of a pair with the Third Quartet, which is serial in technique, and that in performance there is a mandatory 60-to-120-minute silence between them, symbolizing the abyss between one kind of musical practice and another, more fertile one. Ben writes,

It is an amazing grace to have come through an abyss. It is

an amazing grace to see once again that the simplest and purest of

relationships are the means to cope with the multitudinous and complex.[6]

It

seems to me that in this era of economic scarcity and questioning of the great

tradition of classical music, we have reached a temporary endpoint in the

extent of music’s outward development. The achievements of Stockhausen and

Brant with multiple orchestras are going to be difficult to surpass any time

soon, or even equal, and for most of us, even a conventional orchestra seems

out of reach – and when it is within reach, we can’t get enough rehearsal time

to try anything innovative. Exceeding the length of Feldman’s chamber pieces,

Glass’s operas, and John Luther Adams’s sound installations is a daunting and

possibly barren prospect. My prediction for the future, partly based on the

curiosity I’ve been sensing among young composers about microtonality, is that

for the next few decades the impulse for musical innovation will go inward to

its own materials rather than outward. Ben’s notation, his theoretical

framework, and the example of his music have already provided us with a map of

the vast inward musical universe whose exploration will take us decades if not

centuries. I read interviews with pop musicians and classical musicians who say

that everything’s already been done in music, all we can do is repeat. And I

remember the door onto a new universe that Ben opened for me, and I think,

“What in the world are they talking about?”

[1] “Scalar

Order as a Compositional Resource” (1962-3), in Gilmore, Bob, ed., Â Maximum Clarity, p. 10.

[2] “Musical

Intelligibility” (1963) in Maximum Clarity, p. 99.

[3] “Scalar

Order as a Compositional Resource” (1962-3) in Maximum Clarity, p. 14.

[4] “Rational

Structure in Music” (1976), in Maximum Clarity, p. 62.

[5] “Musical

Intelligibility” (1963) in Maximum Clarity, p. 99.

[6] Ben

Johnston, liner notes to Fine Arts Quartet, Gasparo CS 203.

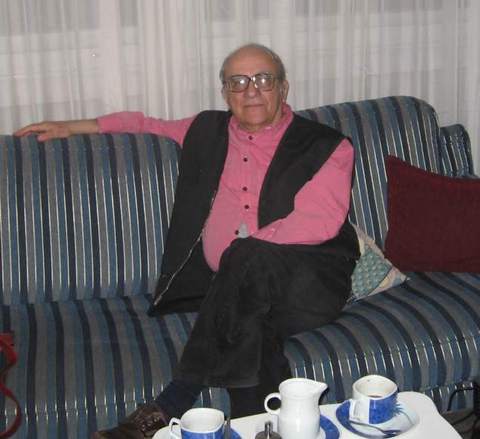

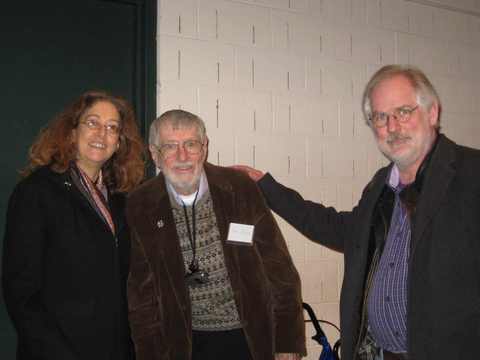

Me and Ben with Momilani Ramstrum at Wright State University, March 14, 2010.

Keeping the Score

The other day I heard a music publisher inveigh against composers who post their scores for free as PDFs on their web pages. I am one of that tribe. His argument, which was new to me and interested me, was that those composers pose unfair competition to the composers whose scores are published, and thus cost money. I have trouble crediting this argument. As much as I’d love to think that my music has an inside track because people can get the scores for free, it’s difficult for me to believe that any performer or ensemble ever makes a repertoire choice based on the cost of the score. The only such cases I’ve ever heard of are orchestras that have decided against performing certain pieces because the orchestral parts cost too much to rent, and those cases didn’t even involve living composers. I suppose it’s possible that if, say, John Adams were giving his scores away for free and David Del Tredici wasn’t, perhaps there are a few ensembles who would choose Adams over Del Tredici for that reason, but I doubt even that. It seems to me that people choose repertoire based on what music fits their ensemble, or their performance technique, or their stylistic programming, and score prices are hardly so exorbitant as to become a determinant.

1. The notation needs considerable work to be readable; these are pieces that are either microtonal (often in indecipherable MIDI notation), or partly improvisatory, or electronically produced without a full score, or incidental music for a dramatic production that would hardly make sense out of context, or otherwise insufficiently notated.

2. Scores that were commissioned by performers who requested temporary exclusivity over performance, and I consider such exclusivity rather expensive, though certainly negotiable.

3. Scores on which I imagine that I could eventually make a considerable amount of money. The only score that falls into this category so far is Transcendental Sonnets, of which I post the orchestral score but not the vocal score or the two-piano performance version. Choral pieces have the potential of selling a tremendous number of vocal scores because so many singers are involved, and so I have thought it unwise to send vocal scores out into the world for free – although I have done that with My father moved through dooms of love, which has no score other than the full score. Since I will gladly send a PDF of the vocal score to any chorus interested in a performance, even this small scruple on my part seems superfluous, though I might change that policy if the piece became wildly popular.

Boulez on Music 22 Years Ago

Today I ran across a box of audio cassettes that has been misplaced for years. Among many treasures are my interviews with Boulez, Yoko Ono, Trimpin, Ashley, Branca, Mikel Rouse, and a few others, plus about ten cassettes’ worth of Nancarrow. I thought the Boulez interview might be of particular interest. It took place in a hotel room in Chicago on October 27, 1987, when Boulez had come to perform Repons and conduct the Chicago Symphony in his Notations and other works. This was back when I’d only been at the Voice a few months, and I was interviewing him for the Chicago Reader, where I’d been free-lancing for five years. The whole interview is 67 minutes, and some of it is a little dated, talking about the impending possibility of classical music’s dying, which of course 22 years later we know is apparently not going to happen. But I’ll put up the most interesting snippets, totaling almost half, from the interview here:

Internalizing Absurdity

My CD of The Planets has arrived. One friend has already received the copy he ordered directly from Meyer Media. You can hear some excerpts there, and I’ve left two movements up on my web site as teasers: Venus and Uranus. And I thought I’d brag a little about what I did in Uranus, one of my favorite movements.

Getting Off the Assembly Line

Your generous responses to my little outburst about being tired of blogging certainly made it clear what most useful direction this blog can continue to go in. I may be out of ideas I haven’t expounded, but my file cabinets and hard drives are still chockablock with music that’s not in general circulation, and listeners are eager to have their experience widened. If I do no more than satisfy that longing, I will have felt that my trip to this planet was not in vain. If I become in the process sort of the Dick Cavett of avant-garde music, so be it.

One of the themes of my life has become something I never expected. I’ve based some large part of my career around documenting recent music not adequately represented by its score notation. It started with Nancarrow. His scores contain all of his notes, of course, but many of them, especially the late player piano studies, don’t provide as much explicit rhythmic notation as is actually inherent. After some brief acquaintance with Nancarrow’s music I formed a theory that, even when it looked like he was rather intuitively splashing notes onto the page, there was always some underlying tempo and even isorhythm to which everything referred. Some painstaking analysis with a little plastic millimeter ruler quickly bore me out, and I found further confirmation when I was able to consult his punching scores – from which he made his final scores, but omitted the messy tempo-grid information.

Since then I have stumbled upon a wealth of music whose score notation, if it exists at all, doesn’t adequately represent it. I reconstructed Dennis Johnson’s November from the recording and score fragments, and have spent time transcribing improvisations by Harold Budd, Elodie Lauten, and others. I’ve reconstructed some of Mikel Rouse’s ensemble music from parts and mathematical models. Harry Partch’s music is indecipherable as to pitch unless you know the various tablatures of his instruments, and, in the case of his Kitharas, I’m told that you can’t figure out the music without knowing how to play the instrument.

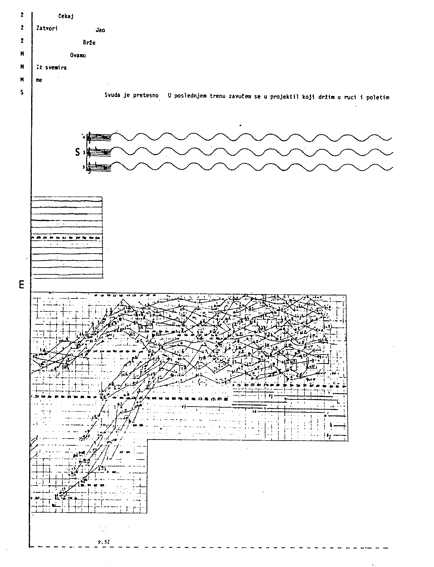

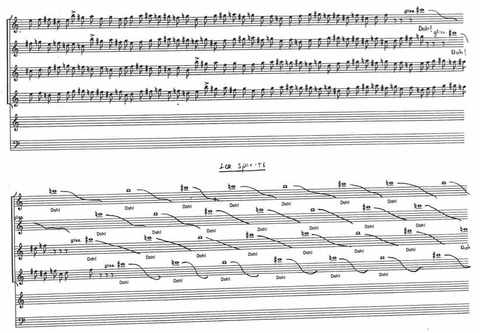

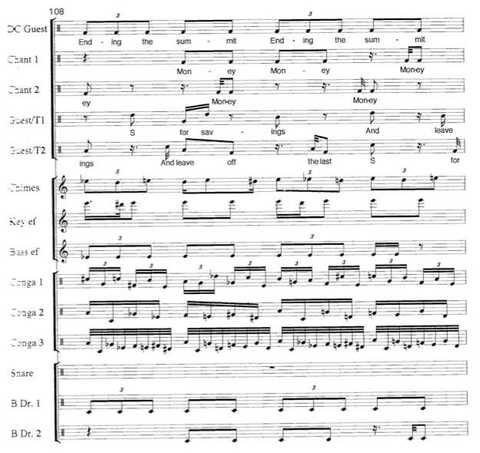

Lately I’ve finally been studying a rather sketchy 392-page score to Meredith Monk’s 1991 opera Atlas that she was kind enough to give me years ago. Meredith refuses to have her singers learn music from notation because it detracts from a lively performance; she prefers to sing their lines and have them sing them back, as in Indian music. The Atlas score pretty much contains the instrumental parts verbatim, but some of the vocal parts are left blank on the page, indicating that they were to be developed in rehearsal. Scores to two of the most beautiful sections, “Choosing Companions” and “Agricultural Community,” contain no vocal parts at all. The “Ice Demons” music, when compared with the recording, shows how precise some of her notation is, how free it is in other places, and how free the singers were to ignore it in either case:

The whole score is a fascinating document of Meredith’s working method. Occasional passages are blanked out, omitted in rehearsal, and where the vocal rhythms (heard here) are exactly notated, the actual performance is often much freer:

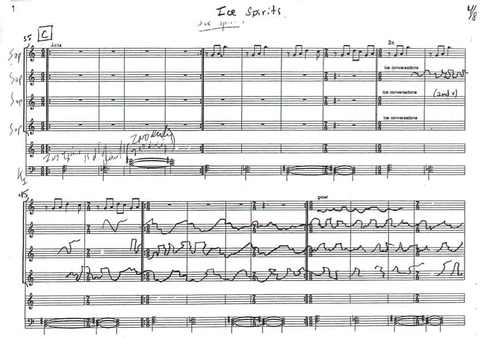

It’s difficult to imagine improving on the unconventional notation of the “Shing Way” section, in which the singers sit in a circle and pass each pitch or figure linearly from one to another (recording here):

I don’t know whether, since 1991, Meredith has made a nicer, more complete score of Atlas, but why should she? This was adequate for a series of stunning performances, and it represents a starting point for the piece, not an end product in itself. Some musicologist could certainly prepare a nice final score using this and the recording as guides, but this one tells more about Meredith’s working method than an engraved Universal Urtext ever could.

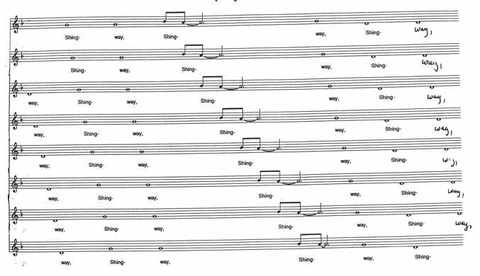

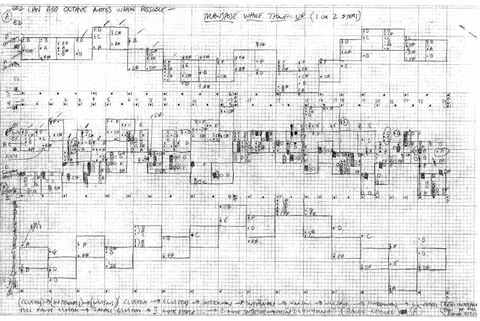

The lack of scores is a big issue for studying Robert Ashley’s music as well; or rather, the discrepancy between his spare working scores, his “production notebooks” as he calls them, and the information overload on the recordings. Years ago when I analyzed Improvement: Don Leaves Linda with a class, Bob kindly gave me the complete MIDI files for the piece, but correctly warned me that they wouldn’t be much help. They were used to trigger events in primitve 1980s software that no current computer still supports, and it’s only here and there that one finds telling correspondences between the MIDI and the recording. Translated to notation, the MIDI files look something like this:

It’s possible that some tracks triggered only markers heard by the performers through headphones, and not by the audience.

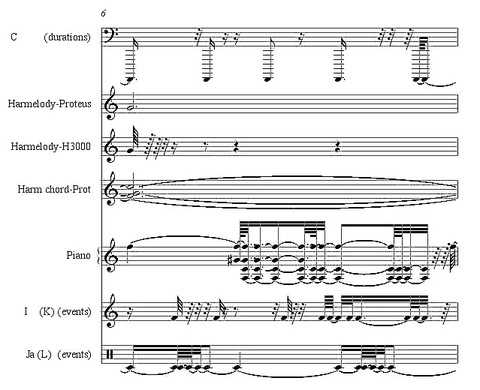

More typically, Ashley’s actual scores contain the libretto marked out in numbered lines, surrounded by harmonic or melodic notations where needed, like this page from Dust:

Ashley takes on the problem of how someone else could perform his operas in an article called “Style and Technique: Performance Practice,” which is collected with his other writings in a dazzlingly huge and mind-challenging new collection of his writings from MusikTexte titled Outside of Time: Ideas about Music, which I will surely be writing more about later. “The solution,” he writes,

is to get all of the operas recorded in a finished form in the most recent format (now, compact discs). Anybody who wanted to produce one of the operas could work from the compact disc, which represents the way the opera is to be performed and how it is supposed to sound. Except for the rhythmic treatment of the words, which remains a notated constant, there is no score from which to make the orchestra. As I have said, the studio production notes for any opera will make little sense in the future, even if I could decipher them now, because they refer to instruments that will be long gone.Â

He talks about a student writing a dissertation on Perfect Lives, to whom he had to explain that a score did not exist.

…about two months later I got in the mail a very accurately transcribed orchestration of the first episode of Perfect Lives, “The Park.”

This is how it should be. The person listened. This is how jazz musicians learn jazz. This is how most of the people in the world learn the music they play. [p. 190]

Like Ashley, Mikel Rouse has a ton of MIDI information in his scores that can’t be deciphered without access to his hardware setup, and can only be documented by reference to the recording. The “chromaticism” in his unpitched percussion parts in this measure from Dennis Cleveland is a dead giveaway:

I also have a pile of one- or two-page scores by David First that I hope to get to someday, marked with little more than noteheads and plus-or-minus-cent numbers. The following page seems to comprise the 15-minute entirety of his piece Distance Receives Permission to Enter from the album Resolver:

You can listen along and follow the whole piece here. I doubt there’s much danger of someone taking the score and arranging a performance independently.

Finally, here’s an intriguing passage, with Totalist rhythms, from Glenn Branca’s Symphony No. 6 for electric guitars, back from his pre-musical-notation days:

In a way there’s a mirror image here, within academic discourse, to 12-tone music. Twelve-tone music and its related forms inspired an immense music-theoretical literature devoted to explaining how the music, opaque as it often is to the ear, is made, and by extension how it is to be heard. Minimalism and its related forms are likewise inspiring a new literature in musicology, for scholars simply trying to document what the music consists of. Famous pieces can be reconstructed from recordings. Partch’s scores get published in just-intonation-notation transcriptions. Even Steve Reich’s celebrated Music for 18 Musicians was apparently notated so idiosyncratically that younger composer Marc Mellits had to do considerable work on the score to make it publishable by Boosey and Hawkes.

The music is worth analyzing. But it is not the composer’s responsibility to make it available for analysis – it is his or her responsibility to successfully bring it to performance. If more is needed for teaching purposes, there are musicologists. As Cage would have added: use them.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Of course, scores like these pose a pedagogical problem. They depart from the universal paradigm for what a score is: a linear continuity on bound paper which contains all the information needed to replicate the piece in performance. The central core of the composition teacher’s job is to teach a student how to write self-contained music for strangers to play. Students have often told me the goal as other teachers have stated it to them: your score should be so detailed and self-explanatory that you can mail it to an ensemble in Japan who are unfamiliar with your music, and they’ll be able to send you back an accurate recording. Of course, I find this ideal illusory at best. I’ve sent pretty clear scores to friends who know my work well, and shown up for rehearsal to find energy levels and tempos all wrong, even with dynamics and metronome markings quite explicit. The truth is, traditional musical notation is at best never an entirely efficient transmitter of an imagined musical sound object. The participation of the composer is omitted at everyone’s peril.

The other truth is, music is not necessarily an imagined sound object (though in academia it is often assumed to be only that). Often it is the result of a process, and emerges only in rehearsal. And the intense conformity to expectation involved in learning to make a detailed conventional classical score is a great reiner-in of imagination and individuality. I see my students wrestle, touchingly, with this problem every year. Some of them are eager to write for orchestra and other conventional classical ensembles, and they want to be taught to notate by the book. Others are used to working in rock bands and alone and with friends, and they have effects they want to try out, experiments they want to conduct in rehearsal, parts that they want to leave to improvisation, rhythmic effects that just won’t conform to a notated meter. Some of them come up with pretty idiosyncratic notations, but they play the pieces and get what they want. Then they decide that they can’t resist that opportunity to write for orchestra for their senior project, and I have to explain at great length what they can expect to achieve with a conventional orchestra in 20 minutes’ rehearsal. They want to put radios in the orchestra, have the players shake boxes of metal debris, improvise with the orchestras at different tempos under two conductors, and so on. (We did manage an amplified toy piano in the orchestra one year.) But the classical performance paradigm is an assembly line, and much of composition pedagogy is involved with teaching them, and limiting them to, what can be achieved by players basically sight-reading what’s been plopped on their music stands. I never push – but some of them decide not to curtail their individuality for the assembly line, and I applaud them after they make the decision. It takes courage.

As one disaffected young composer recently wrote to me about his crucifixion in the academic milieu, “There is no career success outside this horseshit, and no artistic success within it.” That’s pretty close to the truth. But in the long run Ashley and Monk and Rouse have managed pretty enviable artistic lives by working outside the system. It takes a kind of relentless heroism.

So you don’t like the words Uptown and Downtown: fine. But if you deny the existence of this division in order to erase from your consciousness the fact that some of the most creative and original of recent composers have gone outside the classical paradigm to escape its stultifying limitations, then you delude yourself. Our new music suffers more than anything, I think, from a relentless conformism pushed on young composers in the name of “professionalism,” and conformity does not excite audiences. Perhaps we can begin by de-fetishizing the printed score and admitting that it is only a tool, and not always a complete or even necessary tool, that it can sometimes be thrown away once the music exists. Making scores like the above examples available as models for how to go outside the norm, and analyzing the music that goes with them as best we can, may be a start.