A recording of my 2011 orchestra piece Serenity Meditation has arrived, courtesy of the Bowling Green State University New Music Festival, and conducted by J.J. Pearse. The piece, curated for this event by John Luther Adams, is based on three Ives songs, mostly “Serenity” and to a smaller extent “Sunrise” and “General William Booth Enters into Heaven.” It’s dedicated to Neely Bruce, who commissioned the keynote address in which I mentioned those three songs as examples of Ivesian stasis. I’ve had so little experience with orchestras that it’s still a thrilling shock to hear an orchestra play something and realize I wrote it. I wish the microphone had been a little closer to the celesta, which plays a major role, but the performance is quite nice.

Search Results for: www.kylegann.com

November While It’s Still November

When I moved my web site I didn’t re-upload the four-plus-hour recording Sarah Cahill and I made in Kansas City of Dennis Johnson’s minimalist piano classic November. Several people have asked me to reinstall it and I keep forgetting, but it’s up here now. Andy Lee is recording the piece for the Irritable Hedgehog label, so there will be an excellent commercial studio recording out soon. I’ll let you know.

The Schumann of Postclassicism

Since his memorial service I’ve been desperately longing to hear William Duckworth’s Simple Songs about Sex and War, but I couldn’t find my old tape of it. (There’s a commercial CD, but the performance is weird and too disappointing to listen to.) Finally I ran across an mp3 on a hard drive – he and Nora must have given it to me last time I visited – and for all those similarly susceptible I post it here. Based on poems written for Bill by Hayden Carruth, it is the perfect postclassical song cycle, sung by the incomparable Barbara Noska (a Relache member when it was written) in a consummate postclassical vocal style, and with lovely synth accompaniment by John Dulik. Anybody who could write this deserved far more acclaim than the Pulitzer hacks.

Scenario at Last

In 2004 I completed a setting, for soprano and soundfile (tape? CD?) of a wild text by humorist S.J. Perelman called “Scenario.” I haven’t been able to find what year the text was first published, but I suppose Perelman (one of the funniest writers ever, and with an unparalleled genius for wordplay) had been slaving away in Hollywood, where he worked on the scripts for the early Marx Brothers movies. “Scenario” is a stream-of-consciousness satire of a scenario for a movie, a hysterical profusion of not only scene descriptions and actions but bits of dialogue, stage directions, director’s complaints, Hollywood gossip, and other miscellanea. Since, after immobility, stream-of-consciousness collage is my favorite type of musical continuity to compose, I couldn’t resist, and wrote it for the virtual orchestra of my dreams, with impossible tempo overlays and crossfades, occasional microtonality, and including banjo, guitar, harmonica, and a complete set of chromatic timpani. I hired my old friend composer Michael Maguire to realize the recording for me and started looking around for a soprano.

Well, it took eight years to get one to take the bait, and not until Martha Herr came back into my life did I get to premiere the piece, which we did Friday evening to a rather ridiculously small audience (Bard being on fall break). The next day we went into the studio and recorded it, and now you can finally hear Scenario. I’ve always thought it was one of the best, and funniest, things I’ve ever done. Martha started out with the famous Creative Associates at SUNY Buffalo, and first sang my music soon after that period. She sang Babbitt’s Philomel on her college senior recital, with Babbitt in attendance, and was selected by Feldman to premiere his opera Neither, so I was honored to have her premiere Scenario as well. It’s a really difficult piece, 17 minutes with few rests, and dotted throughout with sudden shifts of tempo. She does a superb job, and I can’t tell you what a relief it is to hear, in the flesh, a piece I’ve been singing to myself for eight years. The crazy text is up here, and Perelman’s vocabulary is so arcane that, even with Martha’s excellent diction and a good recording, you probably can’t figure out all the words without reading it.

Well, it took eight years to get one to take the bait, and not until Martha Herr came back into my life did I get to premiere the piece, which we did Friday evening to a rather ridiculously small audience (Bard being on fall break). The next day we went into the studio and recorded it, and now you can finally hear Scenario. I’ve always thought it was one of the best, and funniest, things I’ve ever done. Martha started out with the famous Creative Associates at SUNY Buffalo, and first sang my music soon after that period. She sang Babbitt’s Philomel on her college senior recital, with Babbitt in attendance, and was selected by Feldman to premiere his opera Neither, so I was honored to have her premiere Scenario as well. It’s a really difficult piece, 17 minutes with few rests, and dotted throughout with sudden shifts of tempo. She does a superb job, and I can’t tell you what a relief it is to hear, in the flesh, a piece I’ve been singing to myself for eight years. The crazy text is up here, and Perelman’s vocabulary is so arcane that, even with Martha’s excellent diction and a good recording, you probably can’t figure out all the words without reading it.

I think of it as a 17-minute pocket opera for soprano and CD. Some will object to my use of the term, some to the with-CD format, some to the synthetic creation of orchestral textures, some to the constant intercutting, and many to many other things about it, but I hope a few will be able to hear it for what I consider it, a musical amplification of a wild and comically surreal text, in the intended same vein as Walton’s Facade and Virgil Thomson’s operas.

Some Somethings Echo More than Others

[UPDATED] It strikes me lately that there are basically two types of performances in a composer’s career, or at least in a half-assed composing career like mine. One is, you’re invited to an event, they offer to play a piece of yours, it gets one rehearsal the day before, maybe, and they nominally play it. The other is, a performer (in my case, Sarah Cahill, Lois Svard, Relache, Aron Kallay) chooses to tour with a piece of your music, and he/she/they is/are highly motivated to show the world what wonderful performers they are, and so of course they work their butts off and do a magnificent job, and the piece benefits from repetition in ways that no single performance could effect.

I’m tired of the first category, but luckily I’m about to get a dose of the second, because Los Angeles pianist Aron Kallay, who specializes in microtonal MIDI keyboard, is starting a eastern-half-of-the-country tour this Friday night with some of my music under his arm, including the most recent piece I wrote for him, Echoes of Nothing. Here’s his schedule:

I’m tired of the first category, but luckily I’m about to get a dose of the second, because Los Angeles pianist Aron Kallay, who specializes in microtonal MIDI keyboard, is starting a eastern-half-of-the-country tour this Friday night with some of my music under his arm, including the most recent piece I wrote for him, Echoes of Nothing. Here’s his schedule:

September 28 – Chicago – Heaven Gallery

September 29 – Champaign, IL – SoDo Art Gallery

September 30 – Fishers, IN – Fishers Public Library

October 3 – Hartford, CT – Hartt School of Music

October 4 – Pittsburgh, PA – Carnegie Mellon University

October 5 – Annandale, NY – Bard College

October 6 – NY, NY – The Spectrum New Music Space

The Bard performance on October 5 (in Blum Hall, 8 PM) will include three works I wrote for him, plus a performance by soprano Martha Herr, an old friend of mine and an illustrious singer who premiered Feldman’s opera Neither. Martha is premiering a music theater piece for soprano and electronic background that I wrote seven years ago, called Scenario, based on a surreal S.J. Perelman text.

I’ve been looking forward to these premieres for a long time, and I finally have Aron’s lovely recording of Echoes of Nothing for you. Both movements based on the same tuning, a kind of microtonal, Clementi-ish two-movement sonata, an adagio and a rondo, so to speak:

The Line Between A and B

Some of you may recall the Consumers Guides, the full-page record review columns, that we used to run in the Village Voice. They may still do so, I haven’t looked in years. The format and its accompanying grading system were invented during the late medieval era by the Voice‘s dean of critics Bob Christgau; at least, so the legend was passed down to me by my forefathers, whose knowledge I would never presume to challenge. The grading system was intended to be unalterably strict. A B was the top grade for music that would be considered excellent only by fans of that genre. In order to get an A, a record was supposed to be “beyond category” (in Duke Ellington’s memorable phrase), music that would appeal even to people who didn’t usually listen to that genre. This was an impressively high bar. In other words, if something I reviewed was fantastic but would only appeal to new-music fans, the highest grade I was supposed to award it was a B-plus. A’s were reserved for new music broad enough in its appeal to cross boundaries. I was occasionally called on the carpet, gently, for grade inflation, for being too liberal with my A’s, because I couldn’t stomach giving a superb recording of a Cage chance piece, or a wonderful Niblock drone piece, a B just because its potential audience seemed limited. I fudged.

This category distinction was always something of an unwieldy fiction, because it presumed, especially in the case of new music, a specious link between excellence and accessibility. Strictly followed, it was likely to assign a B to a beautifully performed Milton Babbitt record, and a potential A to one of Steve’s Reich’s more mediocre pieces. Nor was it simply a new-music problem, since the most dynamite heavy metal album was still unlikely to find too many listeners outside fans of that genre. (I remember a small scandal when it was learned that a heavy metal fan in the production department had been quietly nudging the grades upward for metal albums after Christgau submitted them.) Even within one sub-genre, the line could be fluid. I think of Niblock as a hard sell for the average listener, but he’s got an occasional piece so transcendent, so clear in its effect, that I think almost anyone could be bowled over who really gave it a chance – as, sadly, few non-new-music fans were likely to do. That, one could argue, was the purpose of the A/B line, to mark off the truly amazing moments when the music burst beyond its premises.

I started remembering all this in connection with my recent post about literature. Were I a literary critic in this position, I presume I would have to give B-pluses to both Finnegans Wake and The Making of Americans, two books that I think are funny and wonderful and profound - neither of which, I have to admit, I’ve ever finished reading. One of my retirement plans is to read The Making of Americans out loud, which is how I fell in love with it, hearing it read publicly, and, I think, the only way to make it sink home or even make sense. I don’t have time in my life, obviously, for many books in this category. Not having to make my living via my literary expertise, I have the luxury of quitting novels that don’t fairly promptly engage my interest. I don’t mind having to think hard and figure things out, but if I’m going to do that the payoff better be ground-shiftingly transplendent and not held off until the last chapter, or I won’t still be there.

As someone who does make a living off my musical expertise, I have put the requisite brain power into a lot of esoteric works, some of which repaid the effort and some didn’t. I cherish a ton of music in the Voice‘s excellent-but-B-plus category. Maderna’s Grande Aulodia, Christian Wolff’s Snowdrop, Babbitt’s Vision and Prayer, Xenakis’s Bohor, Scelsi’s Fourth Quartet, Rochberg’s Sonata-Fantasia, Stefan Wolpe’s Enactments: these are not pieces that I’d give CDs of to my mother for Christmas, or play to impress non-musicians who come over for dinner, but I love them dearly and will listen to them when alone, even play them for students. In many cases I have inside information about how they’re written, which conditions the way I listen to them and helps me enjoy them more. Enactments, his three-piano piece that I digitized from vinyl this week, is Wolpe’s most austere and relentlessly abstract music, but I understand he used to watch fish in his fish tank to get inspiration for his playful jumps and darts, and I can hear the subtle surprises and twists he sets up, without quite being able to explain them in a way that a non-musician might grasp. On the other hand, there’s all the (equally) great new music I do play for guests and even at parties: David Garland’s songs, Paul Lansky’s Conversation Pieces, Ingram Marshall’s Evensongs, Beth Anderson’s Piano Concerto, anything by “Blue” Gene Tyranny, Elodie Lauten’s Waking in New York, Ben Neill’s Songs for Persephone, Mikel Rouse’s Living Inside Design and Love at Twenty, Duckworth’s Time Curve Preludes, Beglarian’s Five Things, Epstein’s Palindrome Variations, Lentz’s Wild Turkeys, and on and on and on – all that 1980s and ’90s “accessible” music that I suppose marks me as an old fogey at this point, but that most people have still never heard before and can very often be charmed with. Music that, when it comes on in the background, someone stops and says, “Ooh, what’s that? Can we hear it again from the beginning?” Music that I don’t particularly admire more than I do Vision and Prayer or Enactments, but that I could give an A to in a Consumers Guide with a cleaner conscience toward Christgau, because it does reach out to people who aren’t professional new-music mavens (the latter meaning composers, basically).

I think it was the American Mavericks website that had the inspired idea of dividing its listening streams into peanut-butter categories of “smooth” and “crunchy,” one for the accessible “new music” in the postminimalist 1970s sense, the other for more superficially off-putting fare. Of course, crunchy already divides into music that is complicated and multilayered (Carter, Ferneyhough) and music that may be far less structured but harsh and transgressive (Merzbow). Young people of a certain type in any generation will get excited about transgressive music, as separating them off from their parents and peers; I certainly went through such a phase, back when Stockhausen’s Mikrophonie I was about as far as crunchy went. The complicated-analysis style appeals to would-be know-it-alls, true elitists – though perhaps not only to those. In reality, “crunchy” does not guarantee profound anymore than “smooth” guarantees simplistic. “Venus” from my Planets is my most oft-downloaded mp3, with hundreds of hits a month lately; it’s smooth as hell, and I grin to think of all the people who listen without registering the layering of 3/4 and 25/16 meters that runs through it. Postclassic Radio, back when I had it running, was about 96% smooth, and to that extent not fully representative of the wide range of new music I admire. Seduction was the intent.

Grades are silly, and I hope no one was ever fooled (or insulted) by the Consumers Guide categories, but it is interesting to imagine grading pieces not mostly on quality, but on a multidimensional spectrum of opposites with no value judgments attached to either side:

- smooth vs. crunchy

- original vs. traditional

- simple vs. complex

- meditative vs. exciting

- carefully crafted vs. messy

And then with an evaluation thrown in at the end, where Virgil Thomson thought it should be if included at all. Not that pieces of music can be summed up by their generic attributes, as the Pandora people would encourage us to think, but correlating the evaluation to the other sliding scales might reveal more about the biases of the person doing the evaluating. Of those above, my strongest preference leans toward meditative rather than exciting. I often call myself a devotee of the “slow, boring, depressive” aesthetic, and occasionally someone of similar tastes (Feldman, Harold Budd, Eliane Radigue) responds with a twinkle and a nod because they know exactly what I mean. Boring, much as I love it, can be just as effective as transgressively crunchy at relegating music to that B-plus, specialists-only arena.

So this A/B line maps on to my divided consciousness as a composer/critic/reader. I’m glad that crunchy music is out there, but I’m not likely to write any. I want my music on the potential A list for reasons of both personal vanity and ethics. I want my music to grab the listener the way the novels I reread grab me. Maybe I grew up weird enough as a child and just want to be liked, or, as I suspect, perhaps I’m a historical relic of the “accessible” new-music boom of 1977-83, a living fossil conditioned by the ambience of his formative years. I’m happy that my analytical knowledge allows me to listen sympathetically to a lot of music that’s opaque to novices, but I would feel glum if I had to explain about the 3/4 vs. 25/16 before someone could enjoy listening to “Venus” – feel like I’d only half done my job, in fact. A tension between innovation and populism runs through my entire output, and I feel a little guilty when innovation wins. I do not disapprove, either in music or literature, of all that thorny art praised by the elites. Someone’s got to see how far out we can go and still bring something back. As a musicologist I’ll take time to study all the music, no matter how rarefied. As a reader, I’m happy to leave certain reputedly forbidding novels to the experts, unless I get a strong recommendation from someone who similarly has no axe to grind. As a composer, I never want to be relegated to the B-pluses because I didn’t take the time to appeal to more than the experts.

Bendy Pitches

A brief new tuning study for the 232-key piano of my imagination: Romance Postmoderne. As I was playing it, my wife said, “Boy, the pitches in that are really bendy.” Then she looked at me suspiciously and added, “You can’t hear it, can you?” And I had to admit I couldn’t. It sounds so normal to me; I’d love to hear how weird it sounds to other people, but I’ve just grown too accustomed to thirteenth harmonics. The tuning is really elegant, all harmonics of Eb: the odd numbers from 1 to 15 multiplied by each other, an 8 x 8 grid comprising 33 different pitches once the duplicates are accounted for (7 x 11 = 11 x 7, for instance). In other words, eight harmonic series’ each up to the 15th harmonic, based on the 1st, 3rd, 5th, 7th, 9th, 11th, 13th, and 15th harmonics of Eb. Hate the piece if you want, but admit that if musicians could learn to hear these intervals, there’d be enough new material here to invigorate new music for at least the next century. UPDATE: complete tuning chart here.

AFTERTHOUGHT: The main difference between this and impressionism, or bebop harmony, is that there are fewer pivot notes between chords. Except for the 3rd harmonic (V chord), which is a special case and I don’t use it much, any two (potentially eight-note) chords tend to contain only one pitch in common. Of course, the result of that is parsimonious voice-leading heaven.

(Incidentally, I tried to turn the file into an mp3 in iTunes, as usual, and the aiff – which had sounded fine when I made it in Logic – got all distorted. I looked around the internet and found that everyone’s complaining about distortion in iTunes in the latest Mac OS. I had to find an internet audio converter to change the file. What a pain. Damn you, iTunes!)

The Progressive Conservative

At the recommendation of our viola professor Marka Gustavsson, I just finished reading Ian McEwan’s 1998 novel Amsterdam, which she urged on me because the main character is a composer. It’s a brief book and an enjoyable read, but what impressed me most was the insightful realism with which McEwan describes, at considerable length, the composer’s thought process. Here’s his description of the composer, the Englishman Clive Linley, early in the book:

For Clive Linley the matter was simple. He regarded himself as Vaughan Williams’s heir, and considered terms like “conservative” irrelevant, a mistaken borrowing from the political vocabulary. Besides, during the seventies, when he was starting to be noticed, atonal and aleatoric music, tone rows, electronics, the disintegration of pitch into sound, in fact the whole modernist project, had become an orthodoxy taught in the colleges. Surely its advocates, rather than he himself, were the reactionaries. In 1975 he published a hundred-page book which, like all good manifestos, was both attack and apologia. The old guard of modernism had imprisoned music in the academy, where it was jealously professionalized, isolated, and rendered sterile, its vital covenant with a general public arrogantly broken… In the small minds of the zealots, Clive insisted, any form of success, however limited, any public appreciation whatsoever, was a sure sign of aesthetic compromise and failure. When the definitive histories of twentieth-century music in the West came to be written, the triumphs would be seen to belong to blues, jazz, rock, and the continually evolving traditions of folk music. These forms amply demonstrated that melody, harmony, and rhythm were not incompatible with innovation. In art music, only the first half of the century would figure significantly, and then only certain composers, among whom Clive did not number the later Schoenberg and his “like.”

So much for the attack. The apologia borrowed and distorted the well-worn device from Ecclesiastes. It was time to recapture music from the commissars, and it was time to reassert music’s essential communicativeness, for it was forged, in Europe, in a humanistic tradition that had always acknowledged the enigma of human nature; it was time to accept that a public performance was “a secular communion,” and it was time to recognize the primacy of rhythm and pitch and the elemental nature of melody. For this to happen without merely repeating the music of the past, we had to evolve a contemporary definition of beauty…. [emphasis mine]

I am surprised to see how much the opinions of this fictional disciple of Vaughan Williams overlap with my own. I have written myself about the primacy of rhythm and pitch, along with my own apologia for being something of a melodist. Of course I grew up making a sharp distinction between conservative and avant-garde, a distinction that has become harder and harder to define with the passing decades, perhaps to the point of total irrelevance. Even today, though, I would bristle at being called “conservative,” though I fully recognize that some of my ensemble works, those in which, for the sake of performer limitations, I have to restrain my microtonality and ferocious polyrhythms – since I am a pitch-and-rhythm composer – probably seem conservative within the definitions of most working composers. In this respect I feel myself an heir to Henry Cowell and Lou Harrison, two composers who endlessly championed progressive musical ideas, but who also sometimes wrote tuneful, texturally commonplace works under commission. In fact, I once submitted my Transcendental Sonnets for a choral competition, and while I didn’t win, the director sent me a complimentary letter calling the piece reminiscent of choral works by Herbert Howells, Hubert Parry, and other great British conservatives, and said he would look into programming it. I was happy to get a compliment from any direction. And I certainly agree with Clive Linley that academia has trapped music in a barren modernist purgatory, though I don’t think I quite agree with him on the most profitable escape route. (And needless to say, I strongly demur concerning the bankruptcy of late 20th-century postclassical, if not classical, music.) It’s funny, as I sit here working with 37 pitches to the octave and seven tempos running simultaneously, to see my opinions reflected back to me from a 1990s British musical arch-conservative.

A Scriabinesque Geometry

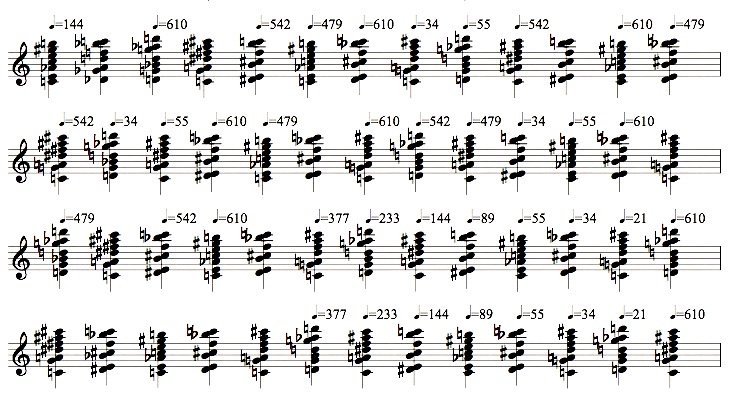

A new, brief piece, a rhythm study: Mystic Chords, 6:20. It’s the most austere thing I’ve written in decades. The main idea of the piece is an attempt to determine rhythms not by duration, but via tempo, thus creating rhythms incapable of metric notation. Here’s an excerpt from the score:

These aren’t the actual pitches. The piece uses a rather wonderful symmetrical pitch set I discovered, 27 harmonics above an extremely low F#, specifically harmonics nos. 1, 3, 5, 7, 9, 11, 13, 15, 21, 25, 27, 33, 35, 39, 45, 49, 55, 63, 65, 77, 81, 91, 99, 117, 121, 143, 169 – or rather, octave transpositions of those harmonics. I’m not much into symmetry; I usually prefer quirky pitch constructions with a scattering of elements that only appear once or twice. But this set creates seven identical chords based on the 1st, 3rd, 5th, 7th, 9th, 11th, and 13th harmonics, containing those same harmonics in each chord.

I called the piece Mystic Chords because I spaced all the chords in fourths after the manner of Scriabin’s famous “mystic chord” – C F# Bb E A D, and I added a G on top. The actual harmonics, then, are stacked as follows, with each chord running vertically:

768Â Â Â Â Â 768Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 800Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 728Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 792Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 792Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 728

576Â Â Â Â Â 576Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 560Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 560Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 576Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 572Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 572

416Â Â Â Â Â 432Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 440Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 392Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 432Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 440Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 416

320Â Â Â Â Â 312Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 320Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 308Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 324Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 308Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 312

224Â Â Â Â Â 240Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 240Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 224Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 234Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 242Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 234

176Â Â Â Â Â 168Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 180Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 168Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 180Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 176Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 169

128Â Â Â Â Â 132Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 130Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 126Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 126Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 132Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 130

The preceding won’t mean anything to non-math geniuses, but dividing each number by the largest possible power of two gives the octave equivalents:

3Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 3Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 25Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 91Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 99Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 99Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 91

9Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 9Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 35Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 35Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 9Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 143Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 143

13Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 27Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 55 Â Â Â Â Â 49Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 27Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 55Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 13

5Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 39Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 5Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 77Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 81 Â Â Â Â Â Â 77Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 39

7Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 15Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 15Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 7Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 117 Â Â Â Â Â 121 Â Â Â Â 117

11Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 21Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 45Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 21Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 45Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 11 Â Â Â Â Â 169

1Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 33Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 65Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 63Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 63Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 33Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 65

Now it’s easier to see that the first column is all divisible by 1 (of course), the second by 3, the third by 5, the fourth by 7, the fifth by 9, the sixth by 11, and the last by 13. Each column contains that number multiplied by 1, 3, 5, 7, 9, 11, and 13, and thus the entire pitch set is all seven numbers multiplied by each other. It’s such an elegant construction, so simple in principle, that I fully expect to be told that someone else has already come up with it. Its benefit for me is that each horizontal line is made of of pitches close together, ranging no further than a whole step and in some cases a half-step. The following chart, showing the same pitches given as cents above the tonic F#, makes this clearer:

702Â Â Â Â Â 702Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 773Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 609Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 755Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 755Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 609

204Â Â Â Â Â 204Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 155 Â Â Â Â Â 155 Â Â Â Â Â Â 204Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 192Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 192

804Â Â Â Â Â 906Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 938 Â Â Â Â Â 738 Â Â Â Â Â Â 906Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 938Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 840

386Â Â Â Â Â 342Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 386 Â Â Â Â Â 320Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 408Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 320Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 342

969Â Â Â Â Â 1088 Â Â Â Â 1088 Â Â Â Â Â 969 Â Â Â Â Â 1044 Â Â Â Â Â 1103 Â Â Â Â Â 1044

551Â Â Â Â Â 471Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 590Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 471Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 590Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 551Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 481

0 Â Â Â Â Â 53 Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 27 Â Â Â Â Â 1173 Â Â Â Â Â 1173 Â Â Â Â Â Â 53 Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 27

And so I have seven tonalities, all related to the central tonality, each chord equivalent in content, with the horizontal lines moving in very small increments and pivot notes among any two chords. It’s a closed, fully transposable just-intonation system. And since harmonics 1, 9, 5, 11, 3, 13, 7 make up an overtone scale (easier to see renumbered 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14), there’s the possibility of deriving a thick web of melodic connections from these 27 pitches. (I could add in the 15th harmonic with only six more pitches, and might, since Harold Budd’s music made me so fond of major seventh chords.) In fact, this is almost the pitch set I used in my recent piece The Unnameable (of which I played the world premiere at the University of Northern Colorado last thursday, at a lovely festival of my music organized by composer Paul Elwood), except that there I used 15/14 instead of the 9th harmonic. Here I use those chords in an extremely minimalist way, but I think I’m going to have to explore them further.

I guess this will be mumbo-jumbo to most readers, but I’m excited about it as extending tonal harmony into new vistas in a surprisingly efficient manner. It took Partch 43 pitches to do what he wanted in 11-limit tuning, and I’ve got 13-limit with only 27. Of course, he used subharmonics and I don’t.

Fallen Among Thieves

I had to change my e-mail address and web site location. I’ve been using Earthlink for 17 years, paying $62 a month (which I understand is rather high), and last month my rate jumped to $562 – that’s not a typo. So I challenged the charges and the bank got my money back, and, looking around the internet, I see that Earthlink has devolved into a gang of thieves: charging people for things not wanted, refusing cancellation, all kinds of stuff, and if you try to complain you’re talking to someone in India whose English you can hardly understand. So anyway, the web site will still be at kylegann.com, but I’m doing a redirect to Hostmonster, per my brother’s recommendation, so there may be some disruption of service. All mp3s hopefully running again soon. My new e-mail address is reachable via the “contact” link on the web site. UPDATE: If there’s any problem with the redirect, find my web page here. And please let me know of links not working.

Here It Is, Your Moment of Zen

New piece: The Unnameable. 12:10

UPDATE: For many years I have been trying to compose using the harmonic series, and in a series of studies for my three-Disklavier piece, including this one, I’ve finally figured out how to do it. The harmonic series in its natural pitch order (high harmonics on top) is a rather thin thing to work with, creating wan parallels. But if in one chord you use the 13th harmonic near the bottom and the 5th on top, and in the next chord you have the 11th on the bottom and the 9th on top, and so on, one can create a wonderful range of variously clear and obscure chords that all make sense, but give subtle tension-and-release patterns analogous to regular tonal harmony, with extremely parsimonious voice-leading. The chords can be almost motionless as the implied tonic zips all over the place. And to do that, I’ve become increasingly reliant on the 13th harmonic; without it, the gap between the 3rd and 7th harmonics made it difficult to keep the melodic intervals consistently small. I suppose it’s the just-intonation version of what beboppers do with the flat and sharp 9, sharp 11, and flat 13. So after years of 11-limit pieces, I’m finding myself ensconced in a 13-limit world, and I can finally really hear that 13th harmonic and anticipate its effects. Don’t know why I’m so obsessed with this paradigm of emotionally fulfilling music that barely moves, it’s just my thing.

The Elusive Incriminating Evidence

I keep hearing that people are seeing Facebook photos of me interviewing Phil Glass. I won’t join Facebook again, and I can’t find them. I would be grateful (perhaps eternally) to anyone who might send me a couple. E-mail address at my website.

What a Guy

I interviewed Philip Glass live in front of an enthusiastic student/faculty audience at Bard tonight. It’s the second time I’ve done such a thing; the first was about 15 years ago in NYC, and Phil and I couldn’t remember what school it was. But Phil insisted on writing my introduction for him, saying, “These students may not know who I am.” And here is the entirety of the autobiographical part he wrote: “He began, as a composer, at the age of 20, and has thus far spent 55 years in this general line of work.” I said to the audience, “If you didn’t know who Philip Glass was, you do now.” He absolutely refused to let me detail his “so-called,” as he put it, accomplishments. He was charming and insightful, as always, and the student enthusiasm was beyond my wildest expectations.

I interviewed Philip Glass live in front of an enthusiastic student/faculty audience at Bard tonight. It’s the second time I’ve done such a thing; the first was about 15 years ago in NYC, and Phil and I couldn’t remember what school it was. But Phil insisted on writing my introduction for him, saying, “These students may not know who I am.” And here is the entirety of the autobiographical part he wrote: “He began, as a composer, at the age of 20, and has thus far spent 55 years in this general line of work.” I said to the audience, “If you didn’t know who Philip Glass was, you do now.” He absolutely refused to let me detail his “so-called,” as he put it, accomplishments. He was charming and insightful, as always, and the student enthusiasm was beyond my wildest expectations.

Let me add that I don’t write much about Glass, partly because I take him so much for granted. In the ’70s I was blown away by Music in Fifths, Music with Changing Parts, Music in Twelve Parts, and Einstein on the Beach, in that order, and afterward I almost quit paying attention, because his music had already had all the effect it could have. His rhythmic cycles and voice-leading became part of my compositional DNA, and into that I stirred Feldman, Nancarrow, Johnston, Young, Ashley, several other composers. At that earlier interview, I told him that I was still trying to rewrite the “Bed” scene from Einstein, and he replied, “So am I.” And a few months ago I was offered an opportunity to have a Glass-related piece performed at a Glass 75th-birthday festival which has now been postponed; but I wrote the piece anyway, titled Going to Bed, based on the chords from that “Bed” scene. The PDF is here. I find his output very uneven, as with all extremely prolific composers, but lately I’ve been enjoying Orion, the Eighth Symphony, and the Tirol Piano Concerto.