Pursuant to requests from our European affiliates, the deadline for submissions to the Second International Conference on Minimalist Music is being moved back to January 31, 2009. Thanks to all those who’ve already submitted – you’ve given us an early idea of what we can expect, and the results are already exciting. Some members of the Society, though, just found the preparation time too… too… too minimal.Â

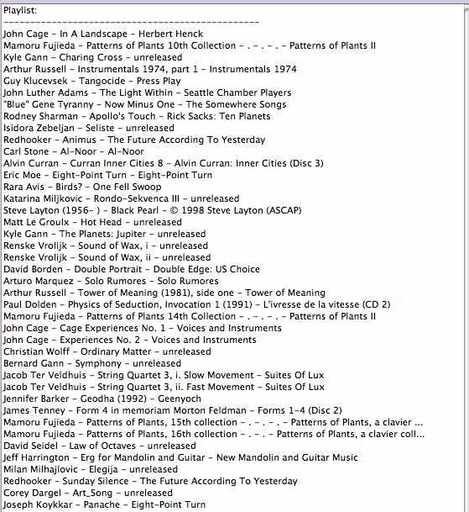

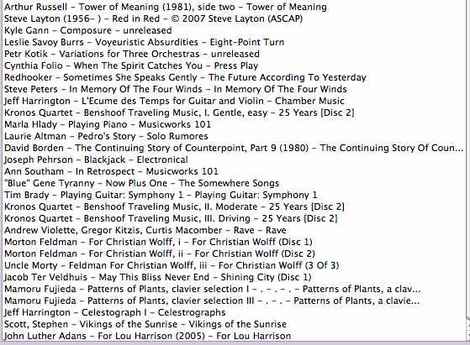

As the Economy Contracts, PostClassic Radio Expands

There’s a lot of new interest in the songwriter/cellist/composer Arthur Russell, who died of AIDS in 1992, because of his work in dance electronica. I don’t know how far the interest extends to his early minimalist music, but I ran across my old Arthur Russell vinyl discs yesterday, and it occurred to me that I’ve never played his music on PostClassic Radio. So I’ve put two records up, Instrumentals 1974 Vol. 2, and Tower of Meaning (1981). Some of the Instrumentals have a nice beat to them, but Tower of Meaning (conducted by Julius Eastman, no less) is pretty austere, just chords in rhythm. But attractive, if you’re into the same kind of no-frills listening I am. The production values are pretty sketchy, some tracks simply cut off in mid-phrase. Imagine a big “[sic]” every time that happens, because that’s what was on the record. Part of being an expert is just having lived long enough to own the records everyone’s forgotten about. I’m sure I had these because Yale Evelev at good old New Music Distribution Service thought I should have them and sent them.

Mirror Image Around the World

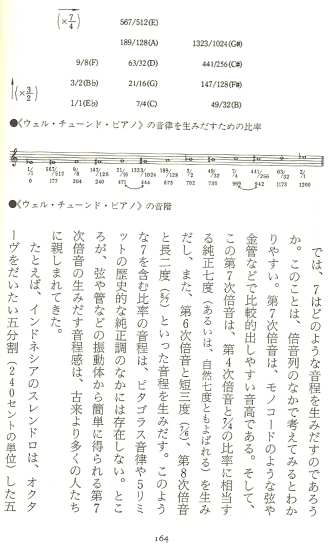

Pianist Sarah Cahill has been trying to get me together with Japanese composer Mamoru Fujieda, and Saturday he and I managed to have lunch in New York. Among other points of commonality, he’s written a book on microtonality (I should say, I am currently writing a book on microtonality; I will always be writing a book on microtonality; I am so wary of the thousands of picayune errors of fact and number that my fellow microtonalists will hit me with, that I am planning to time its publication to occur mere moments before my death, so that their objections will come too late; but anyway, Mamoru has already completed one). It’s titled The Archeology of Sound, only in Japanese, and here’s his discussion of La Monte Young’s Well-Tuned Piano:

Patterns of Plants is a series of compositions based on the melodic patterns that are extracted from the data of slight changes of electric potential found in living plants. Such a procedure was made possible by “Plantron,” an apparatus conceived by bio-media artist Yuji Dogane… The compositional process… starts from finding out “musical values” in the changes of electric potential. By finding out “musical value,” I mean an attitude to regard the changes as “voices of plants” and to gather melodic patterns while listening to their voices.

Daily Challenge

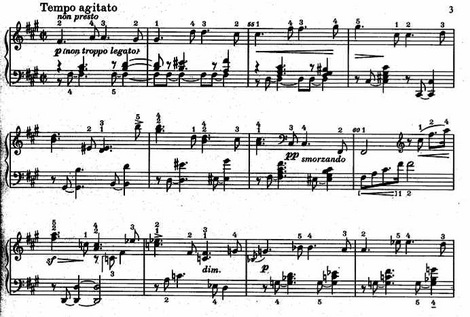

[UPDATE: Anwer below] Don’t you wish your doctoral music exams could have gone on forever? I know I do. And here, just to relive a little of the thrill, is a small test reminiscent of same. If you can guess the composer’s name, you and I have a lot to talk about, but failing that, guess 1. the date of composition, and 2. the date of the composer’s birth. Here’s an mp3 of the passage so you don’t have to drag your computer to the piano.

I Do Love a Good Piece of Writing

Here’s the thing about Americans. You can send their kids off by the thousands to get their balls blown off in foreign lands for no reason at all, saddle them with billions in debt year after congressional year while they spend their winters cheerfully watching game shows and football, pull the rug out from under their mortgages, and leave them living off their credit cards and their Wal-Mart salaries while you move their jobs to China and Bangalore.

And none of it matters, so long as you remember a few months before Election Day to offer them a two-bit caricature culled from some cutting-room-floor episode of Roseanne as part of your presidential ticket. And if she’s a good enough likeness of a loudmouthed Middle American archetype, as Sarah Palin is, John Q. Public will drop his giant-size bag of Doritos in gratitude, wipe the Sizzlin’ Picante dust from his lips and rush to the booth to vote for her. Not because it makes sense, or because it has a chance of improving his life or anyone else’s, but simply because it appeals to the low-humming narcissism that substitutes for his personality, because the image on TV reminds him of the mean, brainless slob he sees in the mirror every morning.

And again:

We’re used to seeing such blatant cultural caricaturing in our politicians. But Sarah Palin is something new. She’s all caricature. As the candidate of a party whose positions on individual issues are poll losers almost across the board, her shtick is not even designed to sell a line of policies. It’s just designed to sell her.

And as a public service announcement, some much-needed publicity for the Alaska Secessionist Movement.Â

Bleak Inheritance

I wrote an article on William Schuman for Symphony magazine, which I’ll give you the details on presently. I couldn’t really spare the time, but chances to write about Schuman are rare, and I love his music too much to have resisted. I gather that being a huge Schuman fan puts me in somewhat of a minority (what else is new?). There is a prejudice abroad that Schuman’s composing career was only propped up by his powerful position as President of first Juilliard and then Lincoln Center. Don’t you believe it.

I met Schuman once. He had some piece played in Chicago in 1986, and I reviewed him by phone for the Chicago Reader, then introduced myself at the performance. I wish I had had the chutzpah to insist on getting to know him. I told him that at home, beneath my bed, was a box of compositions I wrote in high school, most of them attempts to plagiarize the bleak opening atmosphere of his Eighth Symphony. In perfect crusty-old-sea-captain character he growled, “Surely you can do better than that!” Here’s the passage in question, a reiterating series of succulently grim major-minor triads leading to a long, angularly wandering horn solo:

I know it’s fuzzy, but try to look at those two harps and the piano, with tubular bells playing both thirds of the triad and a grace-note in the glockenspiel. Delicious. There are few passages in the orchestral literature I love so dearly. It’s desolate, haunted, almost motionless, yet palpably not despairing; there’s a latent energy to the rhythm and even the subtly shifting voice-leading that somehow forecasts the sardonic fireworks that will come in the third movement. It’s as Americanly tragic (sorry, “tragically American” just won’t do) as The Grapes of Wrath – a novel that coming events may compel us all to reread. I love Schuman’s Third, Fifth, Sixth, and Seventh Symphonies too, and his New England Triptych, and I played his less impressive piano piece Voyage which had a little impact on my piano writing, but the Eighth is the one I kept trying to duplicate.

My guilty secret is that before I discovered Cage at 15, I had already lost my creative vriginity to the Harris Third, the Schuman Eighth, and the Bernstein Second (gang-banged, as it were). My high school composing style slithered around among Schuman, Harris, Ruggles, Copland, Bernstein, and – more consciously but a little more distantly as well – Ives. Had I not then fallen in with the Cage crowd, I suppose I’d be writing symphonies today. And I still suspect that my personal take on minimalism, heard through glacially moving microtones, minor-triad obsessions, and even my fetish for the 11/9 interval (347 cents) that’s halfway between major and minor, was conditioned by the spellbinding effect Schuman’s gloomy chords had on me at a tender age.

I’ll put up a first-movement mp3 here temporarily, but hopefully everyone already knows this piece.

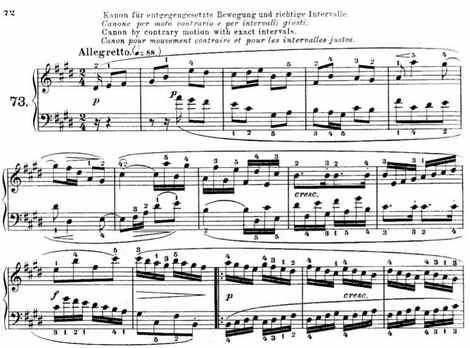

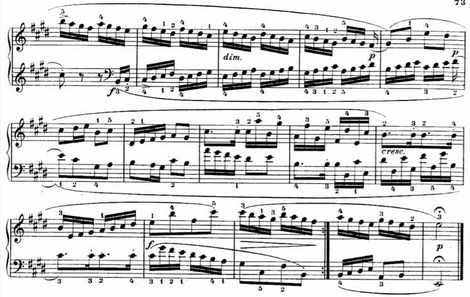

A Clementi Afterthought

You can hear the canon here in a recording by Danièle Laval. Of course in E major he has to reflect the lower voice around F#, because the major scale (as a glance at the keyboard will show, noting D’s position among the white keys) is symmetrical around the second scale degree. Debussy tweaked fun at Gradus ad Parnassum in his Children’s Corner, and Charles Rosen blasts the collection as a marathon of mechanical soullessness. He’s almost 100 percent wrong. They’re all teaching pieces on some level, but included are dozens of lovely, memorable vignettes, variously diverging toward early Romantic harmony and warm neo-Baroque counterpoint.Â

I’ve always gotten a kick out of keeping a secondary musicological specialty besides contemporary American music, sort of as a hobby and to keep new music in perspective. My period used to be medieval, which I studied in grad school with Theodore Karp, one of the leading figures in the field. But the last time I taught medieval, the textbook (by Jeremy Yudkin, the only enjoyably readable medieval music text) contradicted half of what I said, and I realized that that field changes too fast for me to keep track of – pieces are now attributed to different composers than was true when I was in grad school, and even the technical terminology has changed. So several years ago I switched to Classical Era as a secondary specialty, though I only do the instrumental music; most 18th-century opera bores me to tears. I enjoy taking students through the Haydn symphonies because they’re so incredibly varied and numerous, though it’s a rare student who shares my enthusiasm for Haydn. And I try to show them that the period was a lot funkier than it gets credit for, by playing Albrechtsberger’s concertos for jew’s harp, Michele Corrette’s Combat Naval with its forearm clusters on the harpsichord, and music in odd meters like this fugue in 5/8 by Beethoven’s childhood friend Antonin Reicha:

But I bring up Clementi’s inversion canon even in composition lessons as an example of grace achieved under intense compositional restrictions.

Linked Out the Wazoo

Somebody urged me to join Classical Lounge, so I did, and lots of people there wanted to add me to their friends list, and I always pushed the “accept” button. And I started getting notices that people wanted to befriend me on Plaxo Pulse, so I’d go over there and thread my way through the web site, and then the similar LinkedIn requests started pouring in. And I got invited to join NetNewMusic, as did apparently my entire circle of acquaintances, because most of my e-mail time over the next couple of weeks was spent acceding to requests to link to people there. Many of the requests come from slight acquaintances I admire and certainly don’t want to insult by refusing, others come from complete strangers. But in either case, I haven’t figured out what the point is.Â

Classical Reflections

is varied to become the second theme (and later inverted to become the closing theme):

It imparts to Clementi’s sonatas a lovely brand of introversion you don’t find in Mozart or Beethoven, a sense of the theme-hero being inflected according to its changing role in the sonata structure, and the whole movement being narrowly focused. I point this out to demonstrate how this particular sonata exhibits one of the cleverest strategies in leading to the recapitulation I’ve ever found. The development ends up on the dominant of A minor, and a modified form of the main theme emerges, moving ambiguously between e minor and G major, and finally reaching a dominant on G just in time for the second theme:

That means that, thematically, the piece arrives at the recapitulation thirteen measures before it reaches it tonally (i.e., a return to the tonic key), and uses the recapitulation of the main theme as its transitional element modulating back into the tonic. It’s an elegant structural pun, the theme serving to embody, hint at, and retransition to the recap all at once. Very smooth, very clever. Clementi clearly spent a lot of time thinking about the potential subtleties in sonata form and how to play around with them. There are many similar examples in his music (and Op. 37 No. 2 pales next to the six magnificent sonatas of his Op. 40 and Op. 50). And when you compare this level of structural thought and compositional rhetoric to the kind of awkward, slapdash transition that Mozart could jerry-rig in a now-famous sonata even as late as K. 545:

it’s clear that some of the excess idolatry we lavish on Mozart could aptly be retooled as honest admiration for Clementi, and for Jan Ladislav Dussek as well. Not that Clementi ever wrote anything that could match Mozart’s late piano concerti and operas (though he did provide Mozart with a theme for the Magic Flute overture), but it’s kind of silly and sad, given our far more complete view of the 19th century (except for the remarkable Franz Berwald) that we impart such a cartoonish, one-dimensional view of the classical era, just Haydn-Mozart-Beethoven with Gluck occasionally thrown in. Beethoven grew up with Clementi’s sonatas and borrowed from them, and I sometimes wonder what Ludwig thought of poor Clementi, a well-respected composer 19 years his senior, reduced to becoming Beethoven’s publisher and representative of his piano retailer. In my Evolution of the Sonata class, I try to correct the balance.

In Westminster Abbey a few years ago, I ran across Clementi’s grave by accident. (The English adopted him as they did Handel.) It was a thrill to run into someone whose music has given me so much pleasure.

Acousmatics Versus Soundscapers

I truly wish that it had been my lifelong dream to publish books about music, because it comes all too easily to me and I could have fulfilled my dream in short order. Unfortunately, in the late 1960s it became my passion to write music and get it performed, which 40 years later I still find a more challenging proposition (the getting-performed part, I mean). Writing a book is a solitary occupation that sometimes actually pays for itself; putting out a CD requires tremendous enthusiasm from performers and cooperation from sound engineers, plus a vast financial structure to make sure everyone gets paid, with virtually no money guaranteed to come back in return. Each book I publish feels like a cakewalk compared to the CDs I struggle like hell to put together. Yet had I put out 30 CDs in my life and no books, I would have been tickled pink with my career. Instead, I find myself writing a book now and then just to take up the slack.

Cleaning Out My Office

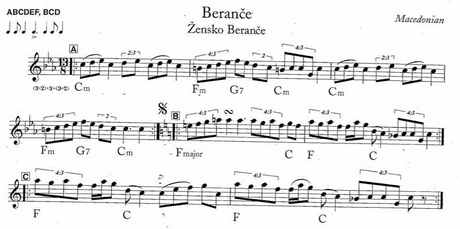

Macho Meters

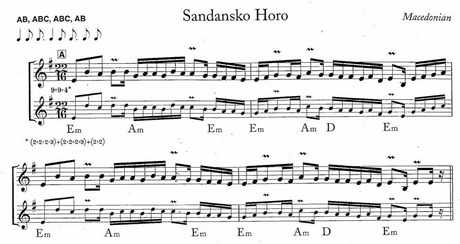

Anyone ready for another year of music theory talk? I did my annual shtick this week on odd meters. You can anticipate me: Holst’s “Mars,” the ancient Greek “Hymn to Apollo,” and Brubeck’s Take Five for quintuple meter; Pink Floyd’s “Money” for seven; a long passage from Roy Harris’s Seventh Symphony, plus a Bulgarian “Krivo Horo” for eleven; the “Blues” movement of Ben Johnston’s Suite for microtonal piano for thirteen; Waylon Jennings’s “Amanda” for fifteen; and the end of the first movement of my Desert Sonata for a long passage in 41/16 meter. Only this year, I have a student, Benjamin Bath, who grew up in a Greek family and going to Greek weddings and all that, and every meter I’d start to mention, he’d reel off all the traditional Greek and Macedonian and Bulgarian songs, and already knew the couple I played. So Monday he brought in a book, The Pinewoods International Collection selected by Tom Pixton and published by NightShade, and let me copy some examples. Try humming through this little number:

[T]he Bulgarians DO NOT count out every “8th” or “16th” note while performing their music. They express them as long and short beats. They actively discourage trying to count it out, and expressed that the only way to hope to begin to play it accurately would be to feel the long and short beats.

Cleaning Up a Life

John Cage’s life is getting sorted out, but you need to pick and choose your sources. David Tudor and Morton Feldman were both Stefan Wolpe students, and nearly everyone says Cage met Tudor through Feldman, but actually (according to Tudor scholar John Holzaepfel), Tudor was also sometime accompanist for dancer Jean Erdman, in whose apartment Cage and Xenia ended up living when they first came to New York in 1942. (Cage and Feldman met January 26, 1950.) Cage knew Tudor first through Erdman.