Sarah Cahill’s premiere of my War Is Just a Racket last night was fabulous. The video her husband John Sanborn made to accompany my piece (which I hadn’t yet seen), was, I thought, with its footage of General Smedley Butler speaking and a dollar bill waving like a flag, the evening’s most apt and imaginative video, and I’m ready to package the music plus video as a multimedia piece. (It does require three screens, though, which will make the video impractical for general use.)Â

Another Jolt in the Paradigm Shift

Yesterday I received a check in the mail from Arts Journal, my first income from the ads over on the right side of your screen. Since 2003 I’ve now made nearly a quarter per entry for all my musings on this blog! – although, if you limit it to the last eight months that we’ve had ads (as I should), I’m really making just over $2 per entry. I’m going to call that pretty damn good for now, considering I started this without a thought of making any money at all.Â

Piano Music to Leave Iraq By

“We must see that peace represents a sweeter music, a cosmic melody that is far

superior to the discords of war,” said Martin Luther King in his Nobel Lecture. Pianist Sarah Cahill took the phrase “A Sweeter Music” for her project of 18 anti-war (or pro-peace) works that she’s premiering this year. I’m happy to say that one concert in that series will take place this Thursday evening, March 12, at 8 at Merkin Hall in New York City, and that it will include the world premiere of my War Is Just a Racket. It’s an odd piece for me, written for a pianist speaking a text while playing, and I hope it works. Sarah’s husband John Sanborn has made video to accompany all the pieces; you’ll recognize the name as the artist who does all of Bob Ashley’s video, and I’m honored to have a connection to his work. The concert is part of Jon Schaefer’s New Sounds Live series, so I guess you’ll be able to hear it on radio as well. The whole program is:

Preben Antonsen (b. 1991): Dar al-Harb: House of War

Kyle Gann (fl. 1440s): War Is Just a Racket

Frederic Rzewski: Peace Dances

Jerome Kitzke: There is a Field

Phil Kline: The Long Winter

The Residents: drum no fife: Why We Need War

Terry Riley: Be Kind to One Another (Rag)

So I’m Neo-Riemannian: Who Knew?

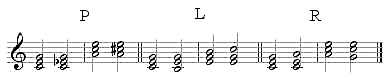

To teach undergraduate music theory is to recount over and over and over, year after year without variation, facts, terminology, and principles that haven’t changed since well before I was born. But Wednesday I managed to teach something new, and got a real kick out of it: Neo-Riemannian theory (named for the German musicologist Hugo Riemann, 1849-1919). I had never heard of the subject until the 2007 Minimalism conference in Wales, where Scott Alexander Cook applied the methodology to the music of Gavin Bryars (PDF). The idea is that relationships between triads can be characterized by variously close or distant pitch replacements, categorized by the three functions P (parallel), L (leading tone), and R (relative). The P function moves the third of a triad to change it from major to minor, or vice versa:

The L function lowers the root of a major triad a half-step, or raises the fifth of a minor triad a half-step, creating a new triad of the opposite modality in either case. The R function raises the fifth of a major triad a whole-step to produce the triad of the relative minor, or lowers the root of a minor triad a whole-step. And there are some other derived functions, such as D, which does from a triad to its dominant, or vice versa. And functions can be combined, so you get PL, RP, LPL, and so on. If I’m oversimplifying or getting it wrong, some kind reader will correct me.

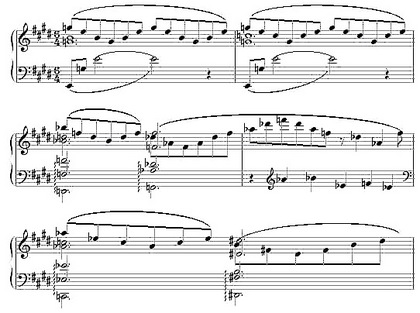

The occasion of my bringing this up was my biennial analysis of a gorgeous passage from Liszt’s Années de Pelerinage, the beginning of “Sposalizio,” which is hardly complicated, but notoriously recalcitrant to Roman numeral analysis:

Now instead of calling that i-VI in E minor and wondering where in hell the B-flat major came from, I could label the sequence L, RLRL (or DD, since C to B-flat is two dominant jumps), PR, D, PR. It doesn’t really explain the music – though the PR does make clear the equivalent jumps from B-flat to D-flat and A-flat to B, which the enharmonic pitch notation hides – it just gives me a way to label Liszt’s key jumps, more radical in their unconcern for tonality than Chopin’s or Schumann’s. And I think the students enjoyed learning a theoretical technique that wasn’t from the musty, immemorial past, but evolved during their lifetimes.

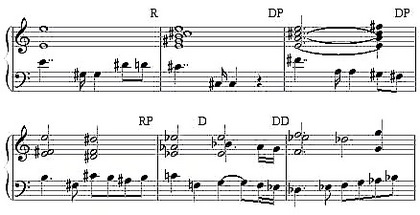

The even greater interest for me is the potential application to my own music. In 1983, I switched over, with some trepidation, to writing in a triadic style, though not at all functionally tonal. I had been studying Bruckner and taking tips from passages like this wonderful one from his Eighth Symphony:

(Interestingly, in the immediate repeat of this passage Bruckner replaces the RP with a PR, and ends up in D major instead of A-flat.) I soon found myself rather obsessed with what I now learn are called LPL and RPR transformations (the latter yielding a tritone transposition). Here’s Baptism, from 1983:

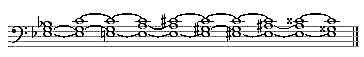

The chord changes, if I have parsed them correctly with my amateur notions of Neo-Riemannian terminology, are PLP, RPR, LPL, RPR, LPL, LPL, RPRP, LPL. Note that no chord change requires fewer than three transformations – that was my conscious discipline for the piece, but of course I wasn’t thinking of it in Neo-Riemannian terms, which hadn’t been invented yet. This was pretty much my default harmonic language from Baptism of 1983 to my “Last Chance” Sonata of 1999. In 2000 I studied jazz harmony with John Esposito, and switched over to bebop chords. My microtonal music uses a process of micro-interval voice-leading that Harry Partch called “Tonality Flux,” related to Neo-Riemannian transformations, but of course not reducible to them. However, the large-scale tonal structure of my 2002 microtonal chamber opera Cinderella’s Bad Magic consists of a chain of simple Riemannian pitch shifts, all tuned to pure triads and evolving from E-flat major to C double-sharp minor, through single note-shifts R P R P L P R P L:Â

These Neo-Riemannian labels neither explain nor justify my music, but they do give me simple ways to refer to my voice-leading methods as classes of harmonic transforms. And, as papers at the last minimalism conference proved, Gavin Bryars and John Adams were using a similar kind of non-functional harmonic consistency from the early 1980s on as well. This terminology can make it easier to point out how the harmonic practices of Liszt, Bruckner, and Reger returned, following the period of widespread atonality, to form a new common practice in minimalist and especially postminimalist music – starting, I think we’d have to say, with Einstein on the Beach, whose “Spaceship” scene may succumb to only this kind of analysis. Neo-Riemannian theory may fill in some cracks in our analysis of Romantic music, when dealing with composers who couldn’t abide within the Germanic idea of a centralized tonality. For postminimalism, it may prove to be the analytical technique that fits the music like a glove.

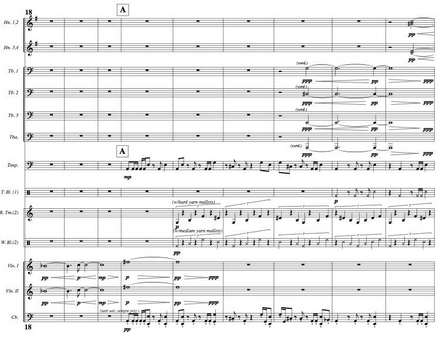

What 2009 Sounds Like, Symphonically

Here is the recording of Robert Carl’s Symphony No. 4 (2009) that I promised you, with Christopher Zimmerman conducting the Hartt School Orchestra. The opening is very quiet. I’ll play it for my “20th-century” Orchestral Repertoire class this week – I just love giving them as much of the 21st century as possible.

End of an Experiment

Like millions of others, I’m feeling the effects of the financial downturn, and, looking around for expenses I can cut down on, my eyes light on PostClassic Radio. The cost of running it has doubled since I started it (to over $600 a year), and I haven’t had time to replenish the playlist lately anyway. I know there are some devoted listeners, to whom I’m grateful, but the listening statistics aren’t very impressive – anywhere from 2 to 20 listening hours a day lately, with the average around 9. I can still put up mp3 music examples on my web site when I need to. I’m proud of my playlist, which I will leave up as a repertoire of hundreds and hundreds of postclassical pieces since 1970, and thankful to all the musicians who allowed me to play their work. Subsidizing the music of others was an important thing to do when I started it, but I don’t think it’s a cost-effective strategy anymore, and I’d appreciate not having that hole in my budget next month. Don’t worry, I won’t quit the blog, which costs me nothing. Thanks to all those who listened (it’ll be up for a few more days if you’re trying to record things), and let’s look forward to the next phase.

The Symphonic Temperament

Friday I drove to Hartford to hear the Fourth Symphony of one of my oldest friends. It sounds strange to say that: Fourth Symphonies are written by dead composers in the history books, or at least by gray eminences who are living out their fame in European seclusion. But it’s true, my old chum Robert Carl has written four of them now, the latest played by the Hartt Symphony Orchestra under conductor Christopher Zimmerman. Robert is chair of composition at the Hartt School of Music.

Robert and I keep trying to remember how we met, which was almost thirty years ago, but we can’t pin it down; he was finishing his doctorate at the University of Chicago, I across town at Northwestern. Aesthetically, we come from rather opposite sides of the tracks, but our lives keep intersecting and paralleling. We’re both transplanted southerners. He studied with Ralph Shapey, and as a critic at the Chicago Reader I championed Shapey (somewhat to the chagrin of my NU music professors) and published a long interview with him, which I still think is good enough to reprint someday. Robert also studied with George Rochberg, whom I’ve found myself championing lately, enough to receive thanks from his widow. We both had brief student experiences with Morton Feldman. I used to write for Fanfare magazine, as Robert does now, which I believe I got him into (or was that Scott Wheeler?). I just completed a book on Cage’s 4’33”, and Robert is about to publish one on Terry Riley’s In C, on the basis of which we’ve invited him to give a keynote address at the Minimalism Conference at UMKC next September (of which, more news soon). And luckily, Robert and I both moved east to schools only a couple of hours apart and both deeply appreciate fine bourbons and single-malt scotches, so you can imagine the rest.

Generally speaking, Robert’s music is far more angular and dissonant than mine, and oriented toward Romanticism rather than Minimalism, but that superficial characterization is misleading. A few years ago I gave a paper for an Ives festival on younger composers influenced by Ives, and Robert was, if not Exhibit A, at least B or C – and we certainly have that much in common. Robert’s music covers a wide stylistic range, with occasional forays into jazz harmony, minimalism, and even Downtown-type sound installation, but he does have a central, most quintessential style which I can only describe in terms of yearning and transcendence. He has little relation to the music that most people would call New Romanticism, even less to neo-, but there is in his music a kind of aspiration to transcend mundane things, such as one might find parallels for in late Beethoven, Messiaen, Ives’s quieter moments like the finale of his Fourth Symphony – and perhaps in Shapey. Robert’s and my educations and preferences overlap considerably, but we’re opposite personality types: I write a cool, steady music in an attempt to calm myself down, and he writes a music of feeling so urgent that it seems to want to burst the boundaries of its sonic container – perhaps to heat himself up? Between the two of us, he is certainly the more easy-going personality.

I think it’s taken Robert a long time to clarify what is truly Carlesque in his music amid the Ruggles-like angularity (his dissertation was on Sun Treader), the Ivesian layering, the Rochbergian style schisms, the Shapeyesque pitch usage, and it’s been exciting to hear it emerge ever more clearly in each new work. His Fourth Symphony was his clearest, most incisive work yet. It was 23 minutes long, in five movements played continuously, though easy to hear as a varied one-movement work. The opening alternated between soft chords in the strings and winds and a jaunty rhythmic texture in the percussion, and you could eventually tell that the string chords were trying to grow, to turn into a theme, against the percussion’s complacent interruptions. This drew the audience into the work by giving us something to identify with and root for. Impressively, the piece built up its argument without the usual continuity devices of themes or (as in so much minimalist-based work) ongoing propulsive patterns, but through textural blocks juxtaposed against one another in a kind of architectural choreography. It’s a technique unrelated to the usual American styles, and I think ends up in what one might call East-European territory. Unlike comparison pieces by Erkki-Sven Tüür, Aulis Sallinen, and others, however, every gesture was musical rather than sonic, if you know what I mean; Robert never goes for abstract effects, but couches each texture with lyrical specificity, and his sense of rhythm is entirely American. It’s a very original work, so engaging that it seemed to go by too quickly, and I’m looking forward to hearing the recording, which I’ll post here for you to hear it too. [UPDATE: Here it is.]

Robert thinks this is the best he’s done at creating a multimovement “symphonic argument” that emerges over the course of the piece. I certainly hear what he means, as I intuit what it means in symphonies by Beethoven, Bruckner, Mahler, Nielsen, and that crowd. I think it’s probably not something I could come up with myself. I haven’t written a symphony, but I secretly consider my Transcendental Sonnets a choral symphony, and my Implausible Sketches for two pianists the symphony I didn’t bother to orchestrate. From those and my clarinet sonata I gather that I feel multimovement form as a group of fairly self-contained movements all related to a center – more than a suite, the order not arbitrary, but not really symphonic, either. The only other friend of mine who writes symphonies, I think, is Gloria Coates (15 so far), and she doesn’t really aim for that sense of cumulative development either. (My friend Peter Garland got so tired of waiting for an orchestra commission that he wrote a long, wonderful symphony for flute, clarinet, and trombone.) My pieces each gradually explore a soundworld that’s felt to be all present from the beginning, which I guess means my music is more about being, and Robert’s is about becoming. Perhaps that sense of becoming, separable into stages, is what’s needed to be a real symphonist. In any case, I’m proud to have such a long-time friend adding original examples to a true symphonic repertoire.

The melancholic, the sanguine: me and Robert Carl (photo by his partner, the sculptor Karen McCoy).

The Poet as Comet

And every molecule of every object here will swell with life,

And someone will be at the door.

Top Six Reasons to Wander in the Wilderness

1. the strangeness of some of the intervals, which give me the thrill of hearing phenomena that I can’t (as a music theory teacher all too used to analyzing music by ear) automatically process and label;Â

2. the stretching of one’s pitch perception toward harmonics higher than the fifth (since the decision to stop with the fifth harmonic was an arbitrary academic mandate of the Italian 17th century);Â

3. the ability to have lots of pitch variety within a very small space (since I’m a minimalist at heart – I rarely listen to Reich and Glass without wishing I could hear it really in tune);Â

4. the extreme chromaticism available (as a lover of late Romantic music like Max Reger, for whom there never seem to be half-steps small enough);Â

5. the pleasure of writing chord progressions never heard before (countering the deadening feeling in my equal-tempered music that there’s really nothing new I can do in the area of harmony); andÂ

6. the tendency toward hearing the actual sound in its totality, as opposed to the filtering out of acoustic beats we have to subconsciously perform to make equal tempered music make sense.Â

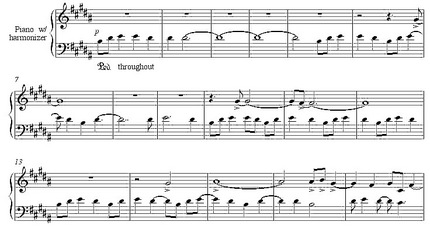

Don’t Shoot the Electronic Piano Player

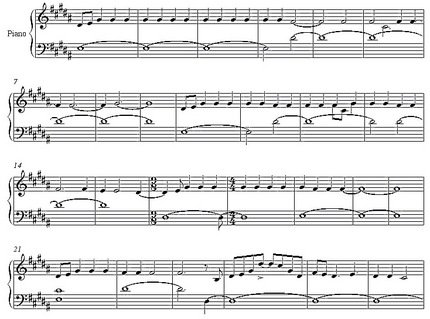

A Problem of Identity

Differences between the two versions are rather spectacular. The Cantil version is five minutes long, the NMA version 23 minutes. The Cantil version begins like this:

The live version begins like this:

Notice that the germinal motive of the recorded version is B-D#-E; that of the NMA version is D#-E-G#. The second motive is, of course, the inversion of the first. The Cantil version stays entirely within the B major scale, without a single accidental. The live version keeps shifting among major scales on B, D, and C#. In addition, the live version has a 12-minute middle section completely lacking in the recorded version, wildly rhapsodic with lots of arpeggios, and moving among major ninth chords on B, Db, D, Eb, E, F, and Gb, never jumping more than a minor third in root movement. This fast section is the hard part to transcribe, but I’m determined I can do it. The recorded version ends in G# natural minor, the live version in C#. On Cantil the lowest note is G# at the bottom of the bass clef, and the highest goes into the piano’s top octave. The live version descends to the lowest A# on the piano, but doesn’t venture as high.

In two diverse recordings of a jazz composition, we know what the identity of the piece consists of: the chord changes, perhaps a head melody. But in what does the identity of an improvised piece like Children on the Hill consist? The two versions have the following things in common: 1. Each begins and ends using a scale bounded by a B-major key signature. 2. Each revolves around a repeating motive of a major third adjacent to a half-step. 3. Each emphasizes repetitions on the F# and G# above middle C, with tonality directed to G# by an A#-B-G# motive. 4. Each climaxes melodically by leaping up to high D#s and G#s. 5. Each employs a consistent quarter-note and 8th-note momentum, except for the middle section of the live version, which is much freer. 6. Each employs different modes within the major scale by emphasizing certain drone notes: sometimes Aeolian, sometimes Lydian, sometimes Phrygian. And certain melodic motives recur in both renditions. Other than that, the identity of the piece can only be more felt than specified: a mood, a texture, an approach.

The recorded version has approximately the same weight, charm, and texture as Cage’s Dream or In a Landscape, and is worthy of them. The live version has all the gravity and formal ingenuity of a Beethoven sonata. I remember it was the first piece played at Navy Pier at the Chicago festival, and I (working as administrative assistant for the festival) arrived at the concert a couple of minutes late. I walked in, heard Budd playing, and stood in the doorway transfixed, as I’m still transfixed by the piece today. The texture looks a little thin on paper, but the harmonizer sustained all the piano tones and blurred them into a resonant wash. And in the fast arpeggio section, the music increasingly introduces melodies bitonally in the wrong key and resolves them by changing chord, a haunting effect. Budd was a tremendous influence on young West-Coast composers like Peter Garland and Michael Byron, and, through his recordings and from a greater distance, also on me. I hope this paper will demonstrate that the complexity and subtlety of not only his music, but his very conception of music, make him one of those minimalist composers who cannot possibly be shrugged off as simplistic.Â

The First Downtown Inauguration After All

Bob Gilmore alerts me to a video that reveals what Yo-Yo Ma and his gang really played at the inauguration. If memory serves, I think it’s an Elliott Sharp tune. Certainly beats John Williams half-heartedly trying to avoid directly plagiarizing Aaron Copland.

It’s the Only Way to Go

Today I was teaching my 19th-century harmony course, starting with John Field’s Nocturnes, and as I was placing my Schirmer edition on the piano, it fell open to the little capsule biography of the composer. By chance my eye lit on the following words:

…He died in Moscow January 11, 1837.

Field’s execution was distinguished for taste and extreme delicacy, and characterized by an extreme ease and placidity of manner which sometimes amounted to a morbid languor and indifference.