I’m off to Turku and Helsinki, Finland, this week where I will be the featured composer at the biennial conference of the Society for Minimalist Music. There will be a concert of mostly my music Saturday night at the Sibelius Academy Music Centre (since there’s “Mostly Mozart,” I’ve always pictured a “Generally Gann” festival), and I am to be interviewed onstage beforehand. It’ll be old friends week, and you can see the conference schedule here. Robert Fink and Jelena Novak are the keynote speakers. I didn’t need to give a paper this year, but I am: “Elodie Lauten as Postminimalist Improviser,” which I just finished today, or at least enough to stumble my way through it. And I imagine I’ll post it here, or at my web site. We have an idea where in the US the next one will be in 2015, and I’ll let you know when it’s official. I think I probably won’t give papers in the future, just go and listen and hang out. I take way too much unnecessary work onto myself.

Hyperrealism: Chamber Music from Mars

You may not have heard of Noah Creshevsky (born 1945), but he is, and has been for decades, one of the most amazing figures in current American music. His music, all electronic as far as I’ve heard, which he aptly terms “hyperrealist,” is a surreal mix of samples, chamber music from Mars. Weird as hell on first listening (and second and third), it nevertheless flows with its own inner logic, and is easily acclimated to. I’ve told him that, if I had the amazing electronic-music chops he has, I’d be trying to do something similar. Perhaps because I just returned from southern Mexico, it strikes me as bearing a kinship to mesoamerican art, very cleanly etched and clear in its intentions yet extraordinarily strange in its shapes and materials. I can’t think of anyone whose aesthetic is more original. He hasn’t received his due because there are so few distribution venues for bizarre electronic music, and because his lifestyle, as he likes to claim, is highly reclusive. Nevertheless, Dennis Bathory-Kitsz wrote a lovely tribute to him in New Music Box several years ago.

You may not have heard of Noah Creshevsky (born 1945), but he is, and has been for decades, one of the most amazing figures in current American music. His music, all electronic as far as I’ve heard, which he aptly terms “hyperrealist,” is a surreal mix of samples, chamber music from Mars. Weird as hell on first listening (and second and third), it nevertheless flows with its own inner logic, and is easily acclimated to. I’ve told him that, if I had the amazing electronic-music chops he has, I’d be trying to do something similar. Perhaps because I just returned from southern Mexico, it strikes me as bearing a kinship to mesoamerican art, very cleanly etched and clear in its intentions yet extraordinarily strange in its shapes and materials. I can’t think of anyone whose aesthetic is more original. He hasn’t received his due because there are so few distribution venues for bizarre electronic music, and because his lifestyle, as he likes to claim, is highly reclusive. Nevertheless, Dennis Bathory-Kitsz wrote a lovely tribute to him in New Music Box several years ago.

So Noah’s newest CD Hyperrealist Music, 2011-2015 is now out on EM records. The first piece on the disc is titled Pulp Fiction, and in it he used samples from my Disklavier CD Nude Rolling Down an Escalator. I think it the best piece on the disc, though not by much, and his use of my rapid piano gestures is extremely flattering, like overhearing myself complimented by strangers. And I obtained his permission to post the piece here, for awhile. You should get the disc, and all his discs, because they’re phenomenal.

Mole and Tequila

A few months ago, I was supposed to be in Italy this week for a totalism festival at Bari Conservatory. That got canceled or postponed due to massive administrative changes at the Conservatory, so maybe it will happen later, or not.

So instead I accepted an offer to lecture at Coloquio PAC in Oaxaca, Mexico, a symposium on contemporary artistic production. Paul Griffiths, José Wolffer, and I will be the speakers on music, and I am supposed to talk for 45 minutes about (clear throat) The State of Music – something I feel I currently know nothing about, except that the public state of music excludes just about any musical ideas I could imagine ever taking an interest in. I’ve got some Usual Things to Say and bits from my blog, and I have to leaven the whole with enough humor and optimism to not become an old man’s rant. I once saw Luciano Berio, whose music I respect and sometimes love, give an old man’s rant about how everything was going to hell, and it was not edifying. Luckily the target of my diatribe is not (and never is) Young People Today but rather the reigning corporate dictatorship which is guaranteed to warp or marginalize any honest musical impulse, and I am hardly the only writer around demonizing that particular bugbear. And if I succumb to gloom, Oaxaca is rumored to be the world center for mole and tequila, two things that could cheer me up even in the direst circumstances.

If I Had a Player Piano, I’d Be on a Roll

Another three-Disklavier piece in my 33-pitch 8×8 tuning:

Futility Row (2015), 8:53

It’s in the key of E-13-flat minor. That is, since my 1/1 is E-flat, the tonic here is the 65th harmonic (major third of the 13th harmonic), 27 cents sharper than E-flat. I have a penchant for minor keys, and it’s difficult to write a minor-key piece in a scale constructed from harmonic series’. I gained a new empathy for Haydn, who, in his minor-key symphonies, always seems to modulate into the major as quickly as possible. Schoenberg remarked that Chopin was lucky because, if he wanted to do something that sounded new, all he had to do was write something in F# major. Well I’m way ahead of Chopin, because not only am I the first to write something in E-13-flat minor as far as I know, I have lots of other exotic keys left to use. This is a particularly Gannian piece in form and gestural style. But I got the idea while humming a song by Mikel Rouse, and so I dedicate it to him, whose music has so often been a means of bringing me back to earth.

I’m Weird

I can now offer the recording of my Snake Dance No. 3 as performed at the Bang on a Can marathon at Mass MOCA on this past Aug. 1. The intrepid performers are David Cossin, Kaylie Melville, Colin Malloy, Wade Selkirk, percussion; Vicky Chow, Karl Larson, keyboards; and Cody Tacaks, bass. It’s a weird piece, the only time I’ve combined the wild percussion rhythms of my Snake Dances with microtonally-tuned synthesizers, in a 19-tone completely irregular scale. I limited the number of pitches so that the fretless bass player wouldn’t have to learn too crazy a scale, given the crazy, tuplet-filled rhythms involved. It is indeed a weird piece. Right after the performance one of the presenters (who might not want to be quoted by name) came up to me and said, approvingly, “That’s a really weird piece.” And several people present mentioned that it stood out on the festival as being different, and that people either loved it or hated it. Glenn Branca and Rhys Chatham not being represented, it was neat to be, for once, the wild, loud piece on Bang on a Can, since I am perfectly capable of writing the kind of tonal, pretty pieces that were otherwise prevalent. It was a really attractive festival.

The word weird grates on me a little bit, since in the signatures in my 1973 yearbook for Skyline High School in Dallas, the word weird is remarkably prominent in almost every entry. I seem to have been the weirdest guy anyone in my high school had ever met. (I was playing atonal piano music by Wolpe and Rochberg in a Texas high school in the early ’70. Some kids concluded, upon hearing me play, that I was completely incompetent.) But even by my exalted standards, this is a weird piece, the farthest out on a ledge my music has ever ventured. The 2010 world premiere by the Sam Houston University Percussion Ensemble was impeccably well played, but technically problematic, since all the synthesizers (including the fretless bass part I myself played on keyboard) were run through a single speaker, and didn’t blend with the percussion at all. I revised the piece for this performance, and I think it’s much tighter, and there will never be a better performance. But I have to admit, it’s a weird piece – perhaps the weirdest piece from an apparently pretty weird composer.

I’ll Take Well-Crafted

Just learned that my song cycle Your Staccato Ways was favorably reviewed by Joanne Sydney Lessner in last Month’s Opera News: “Among the other premieres, Kyle Gann’s Your Staccato Ways stood out for its well-crafted songs, particularly the harmonically restless ‘Couplets’ and the rag-infused ‘Hotel Minor,’ delivered by the appealing tenor Corey Hart.”

UPDATE: And a few more odds and ends – as usual, more for my own bookkeeping than because they will edify you. Roberto Friedman at San Francisco’s Edge Media Network liked my War Is Just a Racket better than anything else on Sarah Cahill’s DC. There is a similarly belated review in Spanish of the Orkest de Volharding CD containing my piano concerto Sunken City. Apparently there is a performance of my guitar quartet Composure coming up on Sept. 3 by the Quarteto Corda Nova in Brazil, at the Sala Ouro Preto of the Hotel Verdes Mares. Never heard about it, I guess they got the score off my web site; I would have been glad to send them parts. And the same site that reviewed Sunken City gave me a big laugh with an article on Steve Reich mentioning that, besides Reich, other minimalists include Glass, Riley, Kyle Gann, Michael Nyman, and La Monte Young. Makes you wonder what’s up with Spanish-language Google.

For Those Who Haven’t Met Me in Person

After every lecture I’ve ever given in the northeast part of the country, at least one person has come up to me afterward and immediately asked, “Where are you from?” I grew up in Dallas, Texas. I left there in 1973. In my youth I had a broad accent, and traces of it remain. If I could time-travel back to visit the twenty-year-old me, I would say, “Kyle, hie thee to a diction teacher post-haste and get rid of that Texas accent once and for all.” It has worked against me throughout my career. For one thing, it kept me out of classical radio, which I suppose was responsible for making me a writer. I almost didn’t get the Bard job because of it. I wouldn’t generally mind having my geographical background automatically commented upon rather than the content of my lecture if it hadn’t become so predictable and repetitious. You may hear me speak someday, and so please file the information away: I grew up in Dallas. Then you’ll be able to skip that part of the conversation, and we can begin at once on some more interesting topic. And bear in mind that people with a regional accent may grow tired of strangers commenting on it.

So Sue Me

I have gone against my most deeply-held principles. I have, for the first time, written a quarter-tone piece. As a just-intonationist, I don’t believe in quarter-tones on theoretical grounds. Quarter-tones provide good approximations for certain eleven-limit intervals: 11/9 (347¢), 11/8 (551¢), 11/6 (1049¢), but the quarter-tone scale emphasizes eleven-based intervals and skips over the seven-based ones. It’s one of my core beliefs that, if we are to accustom the collective ear to assimilate intervals smaller than the half-step, we need to proceed gradually and inclusively up the harmonic series, through seven to eleven to thirteen, and so on. At the same time, I am very fond of Ives’s occasional quarter-tones and pieces by Alois Haba, Ivan Wyschnegradsky, and others in that scale, and so I listen to quarter-tone music as kind of a guilty pleasure: OK for people like me who know by ear what they’re missing, but not the best path for the general evolution of music. It’s always prickly stuff, and my ear enjoys being confused.

So I am to be the featured composer at the minimalism conference in Helsinki next month, and I was invited to write something for the Finnish accordionist Veli Kujala, who has invented a quarter-tone accordion. Well, I love the accordion, and have always wanted to write for it (even though I rather think inventing a quarter-tone one should have been prohibited by law even in Finland), and I couldn’t resist. I took Ives’s article “Some Quarter-Tone Impressions” as my theoretical basis. Ives speculated that the way to build up intelligible quarter-tone harmonies was to build up triads and seventh chords rooted on the perfect fifth, so he gives examples such as C and G with an Eb and Bb a quarter-tone flat (which makes a nice 1/1-11/9-3/2-11/6 just-intonation, neutral seventh chord, though it’s not clear that Ives understood that), and also C and G with D and A a quarter-tone sharp, and C and G with E and B a quarter-tone sharp. And so the piece, which I titled Reticent Behemoth because it growls for awhile and finally breaks into a tune at the end, moves through the quarter-tone scale in fourths and fifths, experimenting with every possible combination of fifths from each of the 12-tone scales a quarter-tone apart. It was a fun exercise, and I really had to teach myself all the quarter-tone combinations. And I guess it will be played in Helsinki at the end of September. Like the recovering drunk who buys a drink at a bar and announces, “I conquered my goddamn will-power!,” I’ve overcome my own theoretical convictions.

Index to My Concord Sonata Writings

My writings on Charles Ives’s Concord Sonata on this blog are now so scattered around that I’ve decided I should index them for those who may be trying to do research, or who simply came late to the party. I’ll expand this as I add more.

The Concord itself:

– MIDI version of the Concord‘s opening

– Some early analytical insights upon looking into Ives

– A more rational ten-part division of the Hawthorne movement

– “Angel” notes in Hawthorne notated

– Analysis of the Alcotts movement

– Ives as reviser

More general aspects:

– Ives’s polytonal chord complexes in the manuscripts

– Transcriptions of Ives’s improvisations on the Emerson material

On the Essays Before a Sonata:

– In search of Lizzy Alcott’s spinet piano

– Ruskin’s influence on the Essays Before a Sonata

– Tolstoy and Hegel in the Essays Before a Sonata

– George Meredith’s relation to Ives

– Corrections to the Howard Boatwright edition of Essays Before a Sonata

What’s wrong with Ivesian musicology, an ongoing series:

– What’s wrong with Ivesian musicology part 1

– What’s wrong with Ivesian musicology part 2

– What’s wrong with Ivesian musicology part 3

– What’s wrong with Ivesian musicology part 4

More miscellaneous thoughts:

– Why we need a new performing edition of the Concord

– Divergences among recordings of the Concord

– Geographical birthplace of the Concord

– A John Kirkpatrick comment about Ives

The First Sonata:

– Geographic origins of the First Sonata

– Compositional technique in the First Sonata

– Ives’s fallible rhythmic notation in the First Sonata

More general Ivesiana:

– Ives, caught between two caricatures

– My keynote address to the Ives song festival

– Refuting charges of Ives’s homophobia

– Refuting once and for all charges of Ives’s homophobia

An Oxymoronically Postminimalist Improviser

Thanks for indulging my mystery pianist contest. I was less interested in stumping the listeners than in collecting a set of comparison pianists to relate the style to. I am grateful to all who obliged.

Not surprisingly, my Downtown comrade Tom Hamilton confidently nailed the answer: it’s our late friend Elodie Lauten, playing her Variations on the Orange Cycle. Elodie was not only an early punk singer, Allen Ginsburg groupie, and composer of beautiful postminimalist operas, but a phenomenal improvising pianist. I wanted to introduce a little of the end of this version, which gets wilder and more dissonant than the style she’s usually associated with; the first long stretch of the recording is rather static (if meditatively beautiful), and I was afraid some people would listen to it, decide it’s simplistic, and turn it off before it got more athletic. Here’s the entire 40-minute recording. Made in a studio on November 21, 1991, it was “released” on a cassette (I have a slew of cassettes Elodie gave me over the years) on her private label, Cat Collectors. (I couldn’t resist including her voice at the beginning.) It has since been rereleased on two of Elodie’s CDs, Piano Works and Piano Soundtracks, and somehow on the former it is transposed up just over a half-step and correspondingly shorter; the cassette was more correct, because the piece is supposed to be in G, and the CD has it between Ab and A.

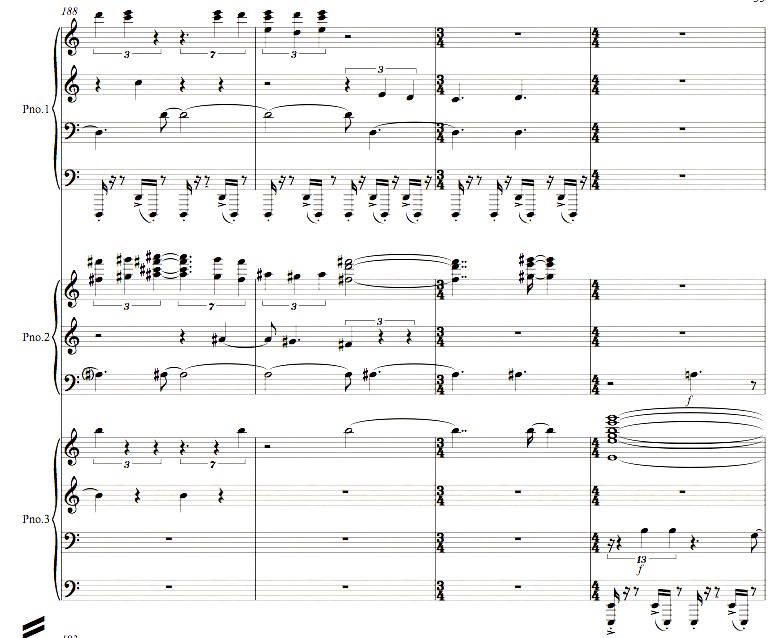

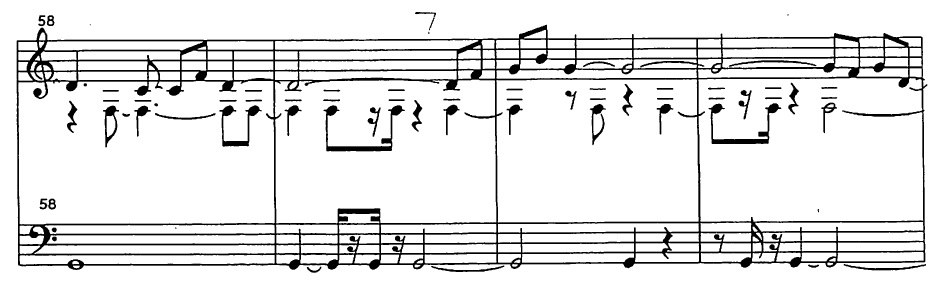

Pianist Lois Svard made another recording of the same piece on the Lovely Music label (with my Desert Sonata on the “flip side,” in fact). What Elodie did for that, in 1995, was to play the piece on an electric keyboard into a computer, recording the MIDI output, and then convert the MIDI input to notation and give it to Lois. Anyone who has experience recording live into MIDI can imagine what a morass of irrational complexity that resulted in, so when Lois despaired of reading it, Elodie took it back and revised a lot of it by hand, though the notation is still a little cumbersome; as you can see here, the left hand alternates between G and F for a long time, but the score has the F in the treble clef, and the rhythms are a little arbitrary:

Lois’s recording, only 25 minutes long, is parsed into four concise, well-shaped movements, which division greatly clarifies what Elodie’s overall plan was. It makes the piece seem stronger and more compact, but I love Elodie’s 1991 recording as well for being a little more all-over-the-place and stream-of-consciousness.

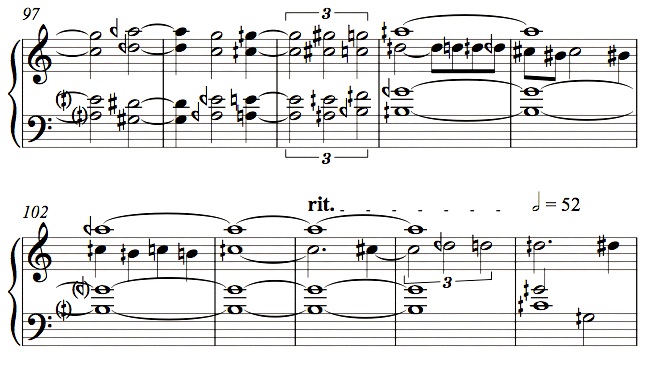

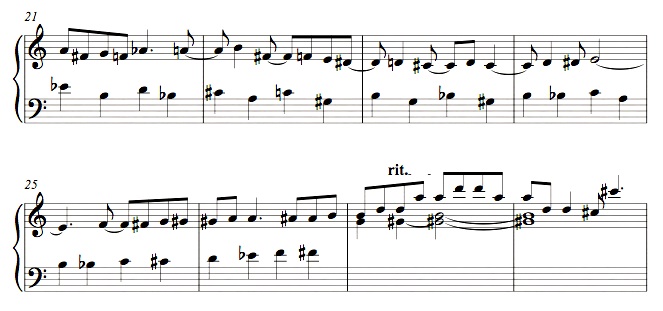

I was afraid the pianist’s identity might be guessed by those who read my blog closely enough to remember that I will be giving a paper, “Elodie Lauten as Postminimalist Improviser,” at the upcoming minimalism conference in Torku and Helsinki, Finland. The bulk of my paper will be on two pieces of which I have two quite disparate recordings, the Variations on the Orange Cycle above, and her Sonate Ordinaire of 1986 – which I reviewed in one of my first Village Voice columns. I have two of Elodie’s recordings of the latter, one an undated cassette copy and the other from Piano Soundtracks, in a performance dated 1986. The former is 17 minutes long, the latter 23, and they’re quite different in form, though distinctly similar in material. The piece’s main material is based on a kind of chromatic sequencing that also appears in the 1991 version of Variations, but not the 1995:

At one point I had hoped that I could prepare an entire performance score for either version of the Sonate Ordinaire, as I did for Harold Budd’s Children of the Hill and Dennis Johnson’s November, but this is looking doubtful; overlapping chromatic lines in the piano’s deep bass are hard to disentangle, and some passages have such rapid flurries that, even electronically slowed down, I don’t know whether I can decipher all the notes with any certainty. As you can see, the rhythmic aspect of most of the piece is straightforward, and I will transcribe what I can. I might also include Elodie’s Adamantine Sonata of 1983, which I don’t have alternate versions of, but I’ve already transcribed the one I have.

I am fascinated by how Elodie could have such a distinct sonic identity for each piece and still introduce so many major deviations from one performance to another – and keep such large structures in her head. Also, there are strong postminimalist traits to these pieces – the first Orange Cycle variation is entirely in G mixolydian, the second mostly in Phrygian, and the Sonate Ordinaire keeps up a steady pulse momentum for most of its length. Postminimalism is a style that has not been conducive to improvisation, and I’m hoping to get inside Elodie’s head and figure out how she conceived the music. I keep thinking I can just call her up to ask questions, and it’s too late.

As always, I will print no comments disparaging another person’s music showcased on my blog, especially for someone so recently deceased and sorely missed. If you feel a need to put it down, ask yourself why.

Name that Pianist

Here’s a three-minute excerpt from a piano improvisation:

The style varies considerably over the course of the excerpt. See if you can guess the pianist or at least tell me who it sounds like – I know many of my readers are far more steeped in the improvisation world than I am. I’ll provide the answer, and the complete 40-minute recording, in a separate post. Thanks for the help.

Every 26 Years Like Clockwork

Believe it or not, my music is featured on this Sunday’s Bang on a Can marathon at Mass MOCA. The last time I had a piece on Bang on a Can was either 1989 or 1990, I can’t remember. They requested, this time, to perform my Snake Dance No. 3, a 2010 piece I’m a little dubious about. It’s the piece in which I added synthesizers and fretless bass playing a 19-tone (non-equal) scale to the core percussion ensemble of my previous snake dances. The piece had some problems at its premiere, which was well played, but there was no attempt to sonically integrate the percussion and synthesizers, and the current recording sounds oddly artificial. There were also some things I didn’t like about it, which this performance has given me the impetus to correct, tightening up the form and melodic lines. I hope it pleases me more this time.

I Can Compose Catholic

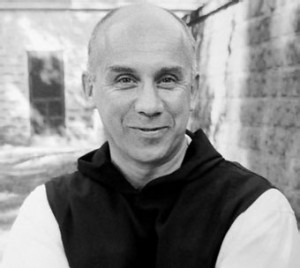

Eleven days ago my friend, colleague, and department chair James Bagwell wrote me to ask me to write a piece for the May Festival Youth Chorus in Cincinnati, which he conducts. The premiere is to take place in a Catholic basilica, and so the text needed to be suitable. Ezra Pound was not going to do the trick. But among Catholic writers I have always found Thomas Merton enormously appealing, and among his voluminous poetry output I quickly settled on In Silence, which begins thus:

Eleven days ago my friend, colleague, and department chair James Bagwell wrote me to ask me to write a piece for the May Festival Youth Chorus in Cincinnati, which he conducts. The premiere is to take place in a Catholic basilica, and so the text needed to be suitable. Ezra Pound was not going to do the trick. But among Catholic writers I have always found Thomas Merton enormously appealing, and among his voluminous poetry output I quickly settled on In Silence, which begins thus:

Be still.

Listen to the stones of the wall.

Be silent, they try

to speak yourname.

Listen

to the living walls.Who are you?

Who

are you? Whose

silence are you?Who (be quiet)

are you (as these stones

are quiet). Do not

think of what you are

still less of

what you may one day be….

It’s a wonderfully mystical poem about silence and listening, and so I used more silence within the piece itself than you’d find in any dozen recent pieces of mine. (I’m kind of a nut about continuous flow – I resisted my instincts this time). It must also be one of Merton’s best-known poems, because my wife remembered the nuns teaching it at Marywood Academy in Grand Rapids fifty years ago.

It is the centuries-old strain of Catholic mysticism that Merton represents that prevents me from becoming quite as cynical about the Christian church – horrifying as I agree it is in most contemporary manifestations – as most liberals are these days, and makes the writing of music with spiritual overtones still a possibility for me. (I had a grad student turn away from my Transcendental Sonnets with a shudder a few years ago because they mentioned God.) I encountered Merton first of all through my readings in Zen, and it was the commonality he could see underlying the original Christianity and Asian religions that gave his writing a not only palatable but attractive depth. One of my favorites of his more-than-seventy books is The Wisdom of the Desert, which is mystic sayings of the church fathers from before Christianity ever became a state (or even tolerated) religion, sort of a collection of Christian koans. In his “Letter to Pablo Antonio Cuadra” Merton wrote,

One of the tragedies of the Christian West is the fact that for all the good will of the missionaries and colonizers… they could not recognize that the races they conquered were essentially equal to themselves and in some ways superior….

If I insist on giving you my truth, and never stop to receive your truth in return, then there can be no truth between us…

Whatever India had to say to the West she was forced to remain silent. Whatever China had to say, though some of the first missionaries heard it and understood it, the message was generally ignored and irrelevant. Did anyone pay attention to the voices of the Maya and the Inca, who had deep things to say? By and large their witness was merely suppressed. [Emphasis in the original]

Merton has an almost Mark Twain-esque streak of sarcasm in his contemplation of the infinitely fallible and self-important human race, and there are other Merton poems I could imagine setting, including Sincerity, a very appropriate poem for our politically divisive times:

As for the liar, fear him less

Than one who thinks himself sincere,

Who, having deceived himself,

Can deceive you with a good conscience.One who doubts his own truth

May mistrust another less:Knowing in his own heart,

That all men are liars

He will be less outraged

When he is deceived by another…So, when the Lord speaks, we go to sleep

Or turn quickly to some more congenial business

Since, as every liar knows,

No man can bear such sincerity.