Allow me to sharpen the source of some of the disillusionment I expressed in my last entry. Part of what I’m going through is the perceived failure of a project on which I’ve spent much of my life’s energy. And yet it hasn’t failed: it has been victorious – and now that it has succeeded, I can see how circumscribed that success necessarily is. As John Cage liked to say, “Success is just another form of failure.”

I have been called “the Downtown academic” – I am hardly the only one to merit the title, but for many years we were few and far between. Incensed in grad school by the way my favorite then-young composers (Glass, Budd, Meredith Monk, Riley, Ashley, Julius Eastman, even Cage, etc.) were scorned by the professors, I began a long-term campaign to prove that music’s worth to academia. I was going to build the bridge from new/experimental/Downtown music to musical academia, and in so doing win some respect for my musical heritage. I can see now that there might have been better uses of my time, but I had built up a good store of the usual Oedipal resentment.

For one thing, many of those composers didn’t give a damn whether academia respected them or not. I strongly suspect that, deep in his heart of hearts, Phil Glass doesn’t lose any sleep over whether his scores are being analyzed in some university classroom. Glenn Branca is infinitely more interested in where his next gig’s coming from, where he’s going to get to travel, and how he’s going to pay the rent than he is in whether I include a score sample of one of his symphonies in my history text. And who can blame them? They’ve got their priorities straight. This campaign of mine was for my respectability, fought with their music as a weapon. Many composers, of course, have been happy for me to champion their music in that rarefied arena, but others have been only middling cooperative. They want to keep control over their own message, or they don’t want their scores circulating, or they just think it’s silly to write scholarly articles about music that was made purely for pleasure, and that adequately reached its intended audience. And who can argue with that? I was building a bridge from Downtown music to the music school, and it was a bridge many Downtowners had no interest in crossing.

But what were my choices? I wanted this music promoted, so that my own music, when it came along, would have more chance of acceptance. As I’ve said, there were three markets: the commercial one, the orchestra world, and academia. I am an introspective, Scorpionic, charismatically-challenged (if intense) personality, and I was not going to start trotting around to Sony and RCA trying to interest their CEOs in recordings of low-commercial-potential new music. The commercial world runs on values inimical to mine, and I was not cut out to play the entrepreneur. [UPDATE: On second thought, though, I guess I played a commercial role as a critic for as long as was feasible.] The orchestra circuit: I know a lot of composers in that world, but I do not hold much sway with them, and they hold even less sway with the conductors and orchestra managers who are in charge. Had I possessed the persuasiveness of a Leonard Bernstein, and held those people in my thrall, they would hardly have had the power to do anything for the music I was championing. Nor were many of the Downtown composers, once again, seeking an entry to that world, though some of them would have certainly welcomed some orchestra commissions.

That left academia. I knew academia, and understood (to a point) how it worked. I was damn good at analyzing music (better than I am now, I’m afraid). I could fluently speak academia’s faux-objective rhetoric of persuasion. I had read all the articles, and I understood very well how the warfare of musical politics gets waged through journal articles under the guise of disinterested scholarship. I could play that game. Furthermore, that world was also the one that had stirred my resentment.

I never set out to write books. I just wanted to write and perform music, and I fell into journalistic advocacy almost by chance, if fatedly. For many years, too, I couldn’t get a teaching job; having finished my doctorate in 1983, I didn’t teach more than an adjunct course here and there until 1995. In retrospect, I can see that this freed me up to get some publishing momentum, whereas had I won myself a teaching job earlier I would probably have gotten mired down, as I see so many young professors do, in the details of teaching and administration, at great expense to their prolificity. I’ve never written a book simply because I wanted to write a book. The books were footholds in academic discourse, credentials, irrefutable proofs that the music I loved possessed qualities worth talking about. And it worked. Had I not written the Nancarrow book and the American history book, I would never have gotten a job teaching theory at Bard. Now I could fire my cannons at the fortress walls from the inside, since I had long observed that academia is impervious to attacks from outside, and indeed disdains them.

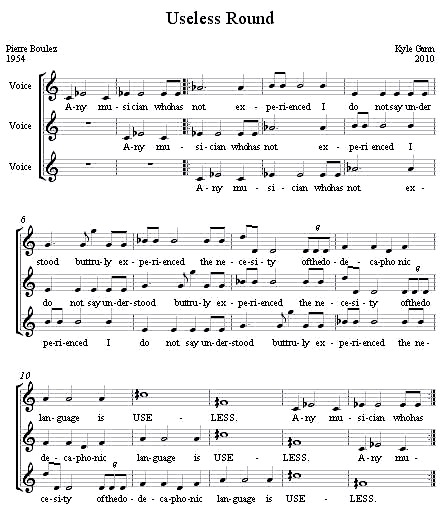

Because I was not firing away alone, my longer-range plan materialized as well. Other scholars, better musicologically trained than myself – Keith Potter, Pwyll Ap Sion, Robert Carl, Robert Fink, too many to list here – also started writing books and articles on minimalism. For the Second International Conference on Minimalist Music, we received paper proposals from 76 scholars working in the field. But I had miscalculated as well in thinking that, once there was a bridge from Downtown music to the music school, that academia would walk halfway down that bridge to meet us. I stupidly supposed that the very quantity of my scholarship would prove to musical academia, in general, that the music was valid. What happened instead was that scholars in minimalism carved out their own niche, their own ghettoized specialty. My writings on minimalism have been celebrated, praised, embraced – in that niche. Within the world of minimalist musicology, I’m one of the grand dukes, a major player. But in the academic composition world in general, with its eternal emphases on Schenkerian theory, set theory, the canon, complexity, hard-core pitch analysis, my work is still taken hardly more seriously than Budd and Monk were when I started out. (I heard my latest dismissive Phil Glass joke from a colleague two days ago, and I’m still looking for a local music professor who knows what Robert Ashley’s music is like.)

In the meantime, I’ve come to understand academia better. I mistakenly thought, from my 1970s student’s perspective, that the problem was that a group of academic composers had gotten ensconced in music departments, and their stodginess and lack of creativity were preventing students from being exposed to the most exciting new music around. I have since learned that a college or university is a particular type of money-siphoning machine, and specifically a type that adheres to values foreign to the commercial world. The lack of creativity goes not from the faculty upward, but from the boards of trustees downward. Wealthy people keep the college system alive, and they do not do so disinterestedly. They want, in return on their investment, a kind of cultural prestige, and a kind that cannot be supported by any rabble-rousing populism among the faculty. Arcane, difficult-to-follow academic work feeds that prestige. Sure, you can write about Laurie Anderson in that milieu – but only if you do so in jargon that talks about “postmodern modes of discourse” and “transgendering,” that makes it abstract and difficult to understand and therefore respectable – which means nonthreatening. Exciting young professors get hired (almost by mistake, it seems) and energize the students, but they eternally seem to have more trouble avoiding getting smashed by the edicts handed down from above than the punctilious ones who cloak their research in measured and arcane terminology. The sciences and social sciences in particular thrive in this environment, and they’re the backbone of the institution. Those professors are in their element, and live honest lives. Knowing them is a constant revelation. The artists, on the other hand, are at a permanent disadvantage. The most creative of them cannot present their work with the kind of empirical verifiability that translates as prestige going up the ladder – except by winning awards administrated by other universities. And those who aim for and achieve any kind of popular or commercial success virtually negate the explicit aims of the institution.

Some of you will smile that I was so naive as to have to learn all this. It was doubtless more obvious from the beginning to many than it was to me. In any case, minimalist music, at least, has succeeded, thanks to me and a few dozen others, in the very dubious aim of carving out its own discourse in the peripheries of music departments. Any good-sized department can now afford one token experimental-music whacko, kind of a court jester. At age 27 I stormed the citadel of musical academia on horseback, with spear and helmet, to incite a revolution. 27 years later, in return for my promise not to break any more of the furniture, I’ve been granted a small but nicely-appointed bedroom on the fourth floor, in the back. Success is just another form of failure.

So now what do I do? I won’t say I don’t want to write any more books, but my motivation for writing them will certainly have changed. I wrote books to cement my credibility in academia (thus freeing my music from any such style-deforming responsibility), but the guilty truth is that, except for the Nancarrow analyses, those books were never aimed at academia: those of you who read them, and who read this blog, are probably either 1. composers and music fans outside academia, or 2. academics with similarly eccentric interests who have your own troubles keeping a foothold in that treacherous world. As a populist by nature, I have pursued a populist agenda in exactly that sphere of life which proudly shelters itself away from the mandates of populism. It was kind of idiotic, now that I think about it. Some of you have pointed that out with more accuracy than I credited you for. A temptation has always lingered in the back of my mind that with my accumulated writing skills I should write books for money; once, in a period of chronic financial panic, I asked Yoko Ono to let me write her authorized biography, but she nicely declined. Today I can’t think of any commercially viable subject that I wouldn’t be disgusted to associate with. And I don’t need any more résumé lines. I have to learn what I would write not to score points, not to advance causes, not to do favors, not to support myself, but simply for my own pleasure. Perhaps this blog, absolutely divorced as it is from the possibility of any conceivable career advantage, is the perfect sketchpad.

It would be narcissistic of me to write what I have just written did I not consider it not only my personal odyssey, but the odyssey of my generation. Thousands of us were appalled by the close-mindedness of the high-modernist generation of professors, and wanted to smash the stranglehold of pitch-set analysis as an ultimate criterion of musical value. Many of us have now proved how far we can go in that direction: impressively far, actually, and yet never far enough. The beast must be fed. Outside of academia, however, we have trouble knowing where to turn. As the corporate dictatorship we live in grows ever more restrictive, popular, let alone commercial, success becomes vanishingly elusive. Academia is the sector of society set aside as a safe haven from corporate control. And yet to pursue a career of quasi-populist yearning for fans within the confines of the ivory tower seems like a weird self-delusion. There’s a story about Thomas Edison making 8000 failed attempts to invent a storage battery, who, on being consoled, replied brightly, “Now we know 8000 things that don’t work.” Perhaps all this is merely to pass on to the younger generation of composers that we now know how far the attempt to cure the problems of authentic art production in a corporate dictatorship can be addressed within the halls of acadème – and it’s not very far. What other ideas you got?