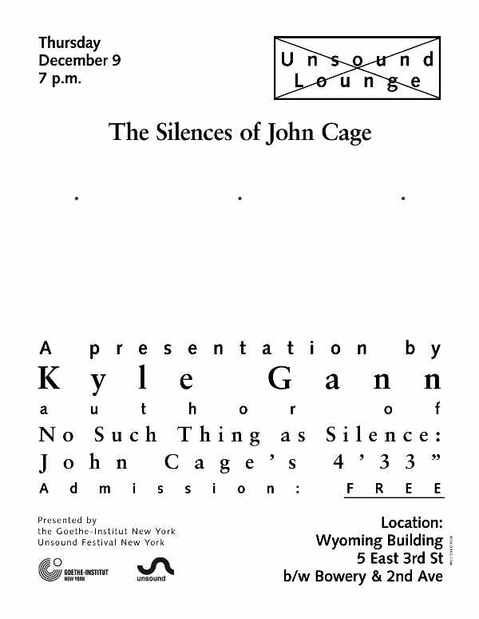

This Thursday, December 9, at 7 PM, I’ll be giving a talk, “The Silences of John Cage,” based on my 4’33” book, at the Unsound Lounge, presented by the Goethe Institute, 5 East 3rd St. between Bowery and 2nd Ave. in New York City. Hope to see some of you there.Â

Taking Away the Mystery

I had an interesting conversation with composer John Halle at a party last night. We were talking about how difficult it is to get information from books and articles about how certain serialist works were written. In European writings on the subject, and certain American academic writings as well, we agreed, it seems to be almost bad taste to state flatly how the rows are derived, what the rhythmic processes are, how the music is actually written. One is expected to know such matters but be coy in expressing them, and to talk more about the implications of the process than the process itself. Personally, I am far more pragmatic: in my book on Nancarrow I gave as much information as I could ferret out about how the pieces were written, exposing every process to public scrutiny. And I was told by a third party that György Ligeti considered my Nancarrow book “too American.” Lately I’ve been trying to get information, for my 12-tone class, about how Stockhausen mapped the row of Mantra onto various “synthetic” scales, and all I find is a quote from Stockhausen about how he dislikes explanation because it “takes away the mystery.” Well, taking away the mystery is precisely what I’m trying to do, to empower my young composers and show them that there are no secrets out there that they can’t use. Mystery exalts the composer, and raises him above mere mortals, who are left to their own creative devices. Every time I write a microtonal piece I put the scale and the MIDI score on the internet, to make sure I withhold no secrets from those who might be interested. Perhaps it’s a foolish career move. But for me the power of the music is in the sound itself, not in the mystification one creates by keeping the generative processes of inscrutable music secret.

Surprise – It’s Me!

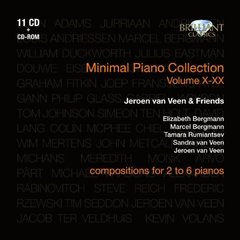

I had a notice from the post office of a package waiting for me, so I stopped to pick it up on the way to school. It was a CD set. I get a lot of those sent to me. This one was Minimal Piano Collection Volume X-XX, a bunch of minimalist pieces for multiple pianos put together by Dutch pianist Jeroen van Veen on the Brilliant Classics label. I had seen the first Volume (I-IX because it contains nine CDs) in Amsterdam, but hadn’t bought it because I already had other recordings of some of the music. So I was glad to get this, and didn’t think too much about it as I was rushing to school – until I turned it over and noticed my own name. And sure enough, Jeroen and Sandra van Veen (with overdubbing) included my Long Night (1981) for three pianos, and I had no idea they were doing it. As I look through my old e-mails, I find that Jeroen did write long ago to express general interest, but I don’t believe he ever told me it was coming out. The other composers in the collection are (take a deep breath) John Adams, Jurriaan Andriessen, Louis Andriessen, Marcel Bergmann, William Duckworth (Forty Changes and Binary Images, which I didn’t know and they’re lovely), Julius Eastman (Gay Guerilla), Douwe Eisenga, Morton Feldman (including the seminal Piece for Four Pianos, which I’d only had on scratchy vinyl), Graham Fitkin, Joep Franssens, Philip Glass, Gabriel Jackson, Tom Johnson, Simeon ten Holt, David Lang (Orpheus Over and Under), Colin McPhee, Chiel Meijering, Wim Mertens, John Metcalf, Carlos Michans, Meredith Monk, Arvo Pärt, Michael Parsons, Alexander Rabinovitch, Steve Reich, Frederic Rzewski, Tim Seddon, Jeroen van Veen, Jacob er Veldhuis, and Kevin Volans (Cicada, great piece).Â

I had a notice from the post office of a package waiting for me, so I stopped to pick it up on the way to school. It was a CD set. I get a lot of those sent to me. This one was Minimal Piano Collection Volume X-XX, a bunch of minimalist pieces for multiple pianos put together by Dutch pianist Jeroen van Veen on the Brilliant Classics label. I had seen the first Volume (I-IX because it contains nine CDs) in Amsterdam, but hadn’t bought it because I already had other recordings of some of the music. So I was glad to get this, and didn’t think too much about it as I was rushing to school – until I turned it over and noticed my own name. And sure enough, Jeroen and Sandra van Veen (with overdubbing) included my Long Night (1981) for three pianos, and I had no idea they were doing it. As I look through my old e-mails, I find that Jeroen did write long ago to express general interest, but I don’t believe he ever told me it was coming out. The other composers in the collection are (take a deep breath) John Adams, Jurriaan Andriessen, Louis Andriessen, Marcel Bergmann, William Duckworth (Forty Changes and Binary Images, which I didn’t know and they’re lovely), Julius Eastman (Gay Guerilla), Douwe Eisenga, Morton Feldman (including the seminal Piece for Four Pianos, which I’d only had on scratchy vinyl), Graham Fitkin, Joep Franssens, Philip Glass, Gabriel Jackson, Tom Johnson, Simeon ten Holt, David Lang (Orpheus Over and Under), Colin McPhee, Chiel Meijering, Wim Mertens, John Metcalf, Carlos Michans, Meredith Monk, Arvo Pärt, Michael Parsons, Alexander Rabinovitch, Steve Reich, Frederic Rzewski, Tim Seddon, Jeroen van Veen, Jacob er Veldhuis, and Kevin Volans (Cicada, great piece).Â

November Again, in December

My article “Reconstructing November,” detailing the process of coming up with a performance score for Dennis Johnson’s epic 1959 piano piece, has just appeared in the journal American Music. I prefer not to repost it on the blog; it contains hardly any more information than I’ve already posted here, here, here, here, and here. It’s available through JSTOR, or will be soon, I guess, for those who have access to that through their schools. This issue of American Music, by the way, is chock full of experimentalism: aside from myself, Maria Cizmic has an article on Cowell’s under-explored piece The Banshee, Zachary Lyman interviews Johnny Reinhard about his controversial completion of the Ives Universe Symphony, David Nicholls’s witty article on the Ultramodernists’ influence on Cage (which I heard him deliver ten years ago) finally appears, and there’s even a review of my Cage book by Branden Joseph, author of a wonderful Tony Conrad book, and a review by Brett Boutwell of John Brackett’s John Zorn: Tradition and Transgression – which quotes me! Whew.Â

The Role of the Idea

I have an article on John Luther Adams’s orchestral music coming out soon in a book about him. In it I describe a condition of his music that is not exclusive to him, and that I think could be profitably expanded upon. And since Carson Cooman and I are currently engaged in a thought-provoking correspondence on the role of the idea in experimental music, I’m moved to try to unfold the concept further here.

My premise is that there are left-brain aspects of music, and right-brain aspects, that can occur independently. My beginning here owes much to the late Jonathan Kramer’s awesome book The Time of Music. The left brain, generally speaking, is verbal, and works by means of logic and analysis and categorization, and also keeps track of time. The right brain, timeless and intuitive, perceives expressive nuance and qualities that are more difficult to put into words. In conventional classical music, or perhaps conventional any music, the LB and RB aspects tend to support each other, though divergenges can be used to create tension. For instance, a tapered decrescendo (RB) at the end of a movement will support a coda’s role of being the end of the piece (LB, since time sequencing is processed by the left brain); or a crescendo can serve the same function, but one or the other tends to happen. (A mezzoforte ending without ritardando is perceived as an interruption.) The transitional theme in a sonata has the logical role, which we perceive (LB) in the harmonic syntax, of creating the tonal ambiguity needed to move to a new key; this is normally accompanied by RB qualities of greater rhythmic restlessness and increased momentum, so that the music’s expressive quality mirrors its logical function. Frequently the composer’s ability to match the expressive feel to the syntactic role is what makes a sonata form more or less compelling. For instance, what seems a little Biedermeier-ish and self-indulgent about Hummel at times is that his transitional themes can be languid and unhurried, and without the razor-sharp harmonic directedness that makes Beethoven’s transitional areas so taut and gripping. There is a slight mismatch between mood and logical function.Â

Of course, classical composers very often intentionally mismatch expression and meaning, as Haydn likes to do by beginning a string quartet with what the right brain clearly recognizes as a closing gesture:

This (from the Op. 50/6 String Quartet, and it’s one of Kramer’s examples) sets up a cognitive dissonance because the left brain knows that the piece is only beginning and that this theme has to fulfill an opening role, while the right brain feels it as a finalizing gesture. I think Beethoven does something similar in the harmonic rhythm of his late piano sonatas: the left brain expects the phrase structure to be defined by the harmonic syntax, but the unpredictability in the timing of his chord changes creates an expressive dissonance, harmony refusing to support the phrase rhythm. In any case, we can posit a kind of musical normalcy in which expressive (RB) and logical (LB) qualities are closely associated in time, with here and there a momentary disjunction to tease the brain and create tension.

There is a branch of (let’s call it for now) experimental music, however, in which LB and RB qualities are radically separated out. The classic paradigm for it is Reich’s Come Out, or perhaps equally Piano Phase. Most people who listen to Come Out, probably even for the first time, know that the phrase “Come out to show them” is going to go out of phase with itself. Since the left brain can grasp this at once and anticipate it, from a logical point of view there ought to be no point in listening to the piece. But what happens is that the texture of that process is completely surprising, and that rhythmic and timbral illusions happen as microbits of the phrase start to perceptually associate with each other. It’s fascinating because you know (LB) that the process is a simple linear one, yet you hear (RB) unexpected patterns that you couldn’t have anticipated. The dissonance between cognition and perception is not just momentary, but globalized across the duration of the piece.

Examples are easily multiplied. JLA’s Clouds of Forgetting, Clouds of Unknowing follows a linear progression from minor seconds in the first section to major seconds, then minor thirds, mixed minor and major thirds, and so on up to major sevenths at the end. (I kid John that when I start hearing tritones I know his pieces are half over, though it’s only true of a handful of them.) If you know what’s going on (and you can figure it out by ear if you listen a certain way), you can keep mental track of the form of the piece. But the sections are so long, and so vaguely textural, that more commonly the mind gives up trying to keep track and can only lose itself in the sensuous surface. And there are other complications: the textures and orchestrations move back and forth among different phases in a huge palindrome that your left brain could track if you were intent enough on it. But again, what’s more interesting is knowing that the music has some kind of order, but losing yourself in the vast color fields of tremolo and arpeggio. There is a left-brain aspect to the piece and a right-brain one, each intriguing, but they operate separately, and not in tandem.

This is not merely a Downtown or post-Cage phenomenon, either; I think (and Carson and I were noting the resemblance) the same principle underlies Babbitt’s and much serial music. For instance, All Set runs through every permutation of the groupings of the six solo instruments. If you have the kind of brain trained to count cards in blackjack, you could conceivably keep track of the groupings as they go by and predict the timing of the piece’s ending. Of course, probably nobody listens to All Set this way. The piece is a riot of wildly changing lines and textures, but one thing that adds to the enjoyment of it is that we know it’s not just a crazy random improvisation, that there’s really a fanatically rigorous symmetry to it of which we’re hearing the results that are too complex to track mentally. Right-brain aspects of the piece are virtually random, but our left brain tries to get us to squeeze the phenomena somehow into the order we know (if only by reputation) is in there somewhere.

Now, I think it’s safe to say that there are listeners for whom this mode of listening is just never going to be enjoyable. They’re used to tons of music in which the expressive and the logical go hand in hand, and if you grab those elements and hold them apart at maximum distance, their brains just won’t derive any pleasure from it. As a non-musician friend once said to me about such a piece, “I’d call it art, but I wouldn’t call it music.” The bit of fun that Haydn had opening a string quartet with a closing gesture has been expanded into a joke whereby the entire piece is not what it seems. Clouds of Forgetting sounds like undifferentiated sheets of arpeggios: it is actually a linear interval progression superimposed over a textural palindrome. All Set sounds like rowdy chaos: it is actually a fanatical symmetry carried out on every possible level. Come Out sounds like a series of complexly related rhythmic patterns: it is actually a mechanically linear phase relationship. One could take examples from Niblock, Glass, Ashley, Xenakis, Tenney, Polansky, Michael Byron, and much other serial or process-oriented (post)minimalist music. Lief Inge’s 9 Beet Stretch is a prime example: it’s just ambient noise until someone tells you it’s Beethoven’s 9th slowed waaaaay down.

One way pieces in this category differ greatly is the extent to which we are tuned into the left-brain idea; it’s much more obvious in Come Out than in All Set. But the idea can influence the way we listen even if we’re only vaguely aware of it. I listen to Music of Changes differently than I do to the Boulez Third Sonata; I know Cage’s notes are the results of a gobal chance process, and that on some level Boulez chose, or somehow placed, each note individually. The distance between sound and idea can also vary infinitely. At some point, perhaps, the sound and idea grow too unrelated so that creative tension is dispelled, and that point may differ for various appreciative listeners. An argument can be made that Clouds of Forgetting can be enjoyed merely sensuously without one even intuiting the underlying organization, but while some are willing to simply “experience” without understanding, I think in general there’s something in us that makes us want our music to make sense, no matter how “meta-” and oblique that sense might be. In any case, I’m not drawing any distinct lines between genres, but using sonata form and process pieces as two extremes that can be clearly differentiated. I can’t even guess where my own music lies along this continuum.Â

“It’s only as good as it sounds” is a favorite motto of mine, but I am too much a new-music insider to be immune to the pleasure of feeling the cognitive dissonance between how a piece sounds and how I know it was written, trying to hear through the notes the structure that I’ve been led to believe is there. If we don’t recognize the final-cadence gesture of Haydn’s opening, we miss his endearing witticism, but if we don’t know that All Set is an elaborately precise structure, we miss the joke of the entire piece. And, to venture back into an old and allegedly discredited terminology for a moment, it seems to me (as I wrote in Music Downtown) that the willingness to separate the sound and the idea of a piece and let them complete each other in the listener’s mind is something that Uptown and Downtown composers shared in common, opposed by the neo-Romantic Midtowners in-between who clung to a more “intuitive” (that Midtown word par excellence) union of expression and meaning.Â

I don’t think I’m saying anything particularly new, nor introducting concepts not in vernacular use. But I do think that a lot of music lovers and a lot of composers think this “boring” brand of music in which the underlying idea is so far from the surface is kind of insane, and that we need a vocabulary for clarifying what those of us who enjoy it hear in it. I also think we need to understand how it works in order to compose it better. Both sides of our brains clamor for fulfillment from music, and Haydn and Adams (and Niblock and Young and Glass) both grant it, even if the difference in scale is so vast as to constitute a difference in kind. Perhaps some people’s brains are simply not wired to enjoy such music: we have no reason to be convinced physiology doesn’t play a role. When we fail to make the distinction explicit, though, I think we set up an undifferentiated new-music world in which Clouds of Forgetting seems obviously more boring next to, say, the Christopher Rouse Trombone Concerto – whereas, in fact, I think its pleasures are greater, though they lie across a different, and perhaps non-obvious, mental plane. [UPDATE: And why does it seem boring? Because the left brain, which keeps track of time, can’t find anything to latch onto – though not necessarily because there’s nothing there.]

Ann Southam, 1937-2010

Warren Burt writes to tell me that Canadian composer Ann Southam died on Thanksgiving day. She only came to my attention two years ago when we both had pieces featured on the same Musicworks disc. So I don’t yet know much about her except that her piano works In Retrospect and Simple Lines of Enquiry are attractively meditative, and seemingly process-oriented in a thoughtful, non-obvious way. Hopefully, as so often happens in such cases, we’ll now be treated to a steady stream from her back catalogue.

Cage in the Mind’s Repertoire

I find it a little odd that, to accompany John Coolidge Adams’s review of Kenneth Silverman’s new John Cage biography, the Times added a little side feature by asking Adams whether he actually listens to Cage’s music. Adams’s answer, in part: “It sounds absurd to say that Cage was ‘hugely influential’ and then admit you rarely listen to his music, but that’s the truth for me, and I suspect it’s the same for most composers I know.”Â

Prophets Outside their Own Country

I have in my possession a handsome book titled Musica per Pianoforte negli Stati Uniti – Piano Music of the United States – by pianist Emanuele Arciuli (EDT). It’s in Italian, but I can read that there are sections on postminimalism and totalism in which I am quoted heavily. I see Daniel Lentz mentioned, and John Luther Adams, Eve Beglarian, Janice Giteck, William Duckworth, Harold Budd, Jerry Hunt, Jonathan Kramer, Ingram Marshall, Mary Jane Leach, Elodie Lauten, Peter Garland, David First, Jerome Kitzke, and other names that formed the daily currency of my Village Voice years. I’m glad at least the Italians get to read about this music.

I have in my possession a handsome book titled Musica per Pianoforte negli Stati Uniti – Piano Music of the United States – by pianist Emanuele Arciuli (EDT). It’s in Italian, but I can read that there are sections on postminimalism and totalism in which I am quoted heavily. I see Daniel Lentz mentioned, and John Luther Adams, Eve Beglarian, Janice Giteck, William Duckworth, Harold Budd, Jerry Hunt, Jonathan Kramer, Ingram Marshall, Mary Jane Leach, Elodie Lauten, Peter Garland, David First, Jerome Kitzke, and other names that formed the daily currency of my Village Voice years. I’m glad at least the Italians get to read about this music.

Symphonic Slide

Listen to this eleven-minute excerpt, and don’t bother clicking unless you’ll commit to the whole thing. It’s the ending of David First’s Pipeline Witness Apologies to Dennis, and I hope the mp3 format doesn’t dumb it down too much. First’s new three-disc set Privacy Issues, on Phill Niblock’s XI label, is the greatest new recording I’ve heard in awhile, and I’ve been relistening to it every few days. It’s all drone-based works from the last 14 years. David’s work is sometimes (amazingly) solo and sometimes ensemble; I picked an ensemble piece here thinking it might have a little more profile over computer speakers, but he can make just as much noise by himself. It’s all music gradually going in and out of tune. You could say that Niblock’s music is the same, and it is, but while Niblock’s music is slow and marvelous and creeps up on you unawares if you have the patience, David’s is considerably more dramatic and high energy. You don’t have to wait for it, it’ll come get you. He’s always been really interested in the liminal area between consonance and dissonance, and the amazing places in his music are those in which you suddenly realize where the music’s going, and you can’t believe it’s about to get there – buzzy and jangling for a long time, but then it starts to slide into tune and this gloriously consonant sonority emerges that you couldn’t imagine was in there. It really feel symphonic to me, like a symphony stripped down to just its harmony, and blurred; Carl Nielsen comes to mind, because Nielsen has these great harmonic clashes in which some major key wins out in the end, and it does in First’s music too, just far more gradually. I wore out three laptops trying to make First famous via the Village Voice, and I’m thrilled that after a long silence he’s got this incredible CD set out, every piece a knockout. I wish I could write music like this, but I can’t. I tried. I just can’t make anything work without a melody to it, but some of First’s passages almost sound like you could analyze them with Roman numerals, except for the buzzy parts in-between. If I were a young composer today this would be my Stockhausen, except that First is already older than Stockhausen was when I was a teenager. In a sane world, grad schools would be hosting conferences on this music, but everything’s so conservative these days that it’s more fringe now than it was 20 years ago.Â

Listen to this eleven-minute excerpt, and don’t bother clicking unless you’ll commit to the whole thing. It’s the ending of David First’s Pipeline Witness Apologies to Dennis, and I hope the mp3 format doesn’t dumb it down too much. First’s new three-disc set Privacy Issues, on Phill Niblock’s XI label, is the greatest new recording I’ve heard in awhile, and I’ve been relistening to it every few days. It’s all drone-based works from the last 14 years. David’s work is sometimes (amazingly) solo and sometimes ensemble; I picked an ensemble piece here thinking it might have a little more profile over computer speakers, but he can make just as much noise by himself. It’s all music gradually going in and out of tune. You could say that Niblock’s music is the same, and it is, but while Niblock’s music is slow and marvelous and creeps up on you unawares if you have the patience, David’s is considerably more dramatic and high energy. You don’t have to wait for it, it’ll come get you. He’s always been really interested in the liminal area between consonance and dissonance, and the amazing places in his music are those in which you suddenly realize where the music’s going, and you can’t believe it’s about to get there – buzzy and jangling for a long time, but then it starts to slide into tune and this gloriously consonant sonority emerges that you couldn’t imagine was in there. It really feel symphonic to me, like a symphony stripped down to just its harmony, and blurred; Carl Nielsen comes to mind, because Nielsen has these great harmonic clashes in which some major key wins out in the end, and it does in First’s music too, just far more gradually. I wore out three laptops trying to make First famous via the Village Voice, and I’m thrilled that after a long silence he’s got this incredible CD set out, every piece a knockout. I wish I could write music like this, but I can’t. I tried. I just can’t make anything work without a melody to it, but some of First’s passages almost sound like you could analyze them with Roman numerals, except for the buzzy parts in-between. If I were a young composer today this would be my Stockhausen, except that First is already older than Stockhausen was when I was a teenager. In a sane world, grad schools would be hosting conferences on this music, but everything’s so conservative these days that it’s more fringe now than it was 20 years ago.Â

Reeling from a Masterpiece

In anticipation of a seminar I’m teaching on the Concord Sonata next spring, I’m finally reading through the selected Ives correspondence published a few years ago by Tom C. Owens (U. of California Press). I feel a little guilty reading the sweetie-pie letters between Ives and Harmony during their engagement, never meant for my prying eyes, but I’m fascinated by the responses he received to the Concord itself when he mailed out privately published copies to total strangers in 1921. This one was from John Spencer Camp, a Hartford music critic:

…You have evidently aimed at impressionistic word pictures, striving to avoid the commonplace and trivial. Whether your musical inspiration has been able to meet the demands you have placed upon it is an open question, and one I should like to defer until I hear your sonata adequately performed. My present impression is that, in spite of the great amount of work you have put into this composition, the fundamental inspiration and glow are lacking. It is, however, a very interesting work. I question whether in the interest of musical beauty such an effect as you call for in page 25 [clusters played with a stick of wood] is good. A “strip of board” does not appeal to my sense of artistic piano music….

…As for the “music,” I confess with thousands of others who have seen it, that it is incomprehensible to me. I do not ridicule you, I do not criticize you, philistine-like, because it would do no good anyway, so all I venture to say at this time is that I hope you will find pleasure in the satisfaction of understanding what you yourself have set down in the seventy pages of your work! No doubt it took a great deal of time to prepare all that notation… Were you not, perhaps, trying to put into “form,” expressions that were entirely (to use a term of our Theosophical friends) ASTRAL – with a modus operandi that granted only PHYSICAL possibilities? This is not sarcasm because I do not mean it as that….

I wish you to know that I do not take your work lightly. I say, frankly, that I do not like this manner of sound-association, for I am too fully grounded in the habits (I admit that they are, to some extent “habits”) of the classic methods. To my mind, these classic methods are correct ones for I find them, in every detail, confirming the eternal physical laws which govern tone as well as stone. But I am not, in conviction, a heartless and brainless conservative, who recognizes the “Last Word” in anything that Bach, Beethoven, or Brahms have said in tone – no, nor Ives. And therefore these newer methods, or experiments, interest me keenly. And, since I am absolutely convinced of your sincerity, and see many admirable evidences of that logic, which is a part of my pet physical law, in your work – note that I hesitate to call it “music,” for I believe in accurate definition – I declare that these experiments of yours interest me particularly….

As for the accompanying book Essays Before a Sonata, composer Henry F. Gilbert commented:

I was very surprised to receive such a book from a musical composer. I showed it to a friend of mine (one of the Boston critics) and called his attention to certain striking passages. He was most interested and enthusiastic but said: “Depend upon it, this fellow is a bad composer – good composers are usually non compos mentis on every other subject.”

The Aging Professor

I am surprised to realize how much difference age makes in my teaching routine. Generally speaking, the older I get, the less students pay attention to me – and, admittedly, the less patience I often have for them. This doesn’t apply to the students who have a particular interest in my areas of specialization, nor to the ones whose ambitions I applaud and encourage. Those students are as devoted as ever. But it does seem to apply to the casual students, the ones who take my general theory courses to fulfill requirements. I can guarantee that I’ve been using many of the same first-year theory pedagogical routines for sixteen years now, and far from them feeling stale, I think I’ve refined them and perform them with more energy than ever. But it doesn’t matter – when I was in my early 40s, a little younger than their parents, the casual students saw me as a role model, potential ally, and someone to identify with. They laughed at my jokes, hung on my every word, and appealed to me for help when the older professors were unsympathetic. Now, just noticeably older than their parents, I’m already an old man to be politely smiled at occasionally and then turned away from. They take their personal problems to my younger colleagues, which is admittedly a blessing. I have to confess to a reciprocal decline in sympathy; excuses I’ve heard 75 times have a blunted impact, and I’ve grown better at predicting which ones will not fulfill their promises. Worst of all, this semester, for the first time in my life, I’ve had to turn disciplinarian. I’ve always encouraged creativity in theory class, emphasizing the freeing effectiveness of the rules once they’re understood rather than imposing them as a restriction. But – and as students do go through generational changes, I can’t be sure of the cause and effect – I’m finding lately that rather than joining me in creativity, they take it as license for rowdiness and distraction, and I have to clamp down. Teaching becomes a chore. I am unusual among my friends in that I’ve never come to mind teaching the fundamentals of theory every year, but lately I’m beginning to fantasize about turning it over to someone else.

Reputations Never Die

I occasionally get invited lately to visit music departments and lecture about my own music “and/or the current scene.” I appreciate that one of my functions in academia is that I will expose the students to crazy music that the resident faculty won’t touch with a ten-foot pole. But I’m always surprised that anyone ever supposes that, given the choice of talking about my own music or someone else’s, I would ever waste a sentence on someone else’s. For one thing, I know very little about the current scene: I can describe the Downtown scene of the 1980s and ’90s in great historical detail, but like most composers of a certain age, I’ve quit paying attention. I don’t mind being paid to lecture on one of my topics of musicological research, whether Nancarrow, Cage, totalism, whatever, but if you’re looking for enthusiasm rather than dutiful professionalism, ask me about my own music. If I thought Glenn Branca, David Lang, and Diamanda Galas were out there lecturing about my music, I might reciprocate by lecturing about theirs, but something tells me this isn’t going to happen. I agree that composers in college ought to be exposed to less mainstream forms of musical creativity, but it’s time for composition teachers who think so to start doing that on their own. Please, if you’re interested in bringing me to your department, don’t expect me to dilute the interest in my own music by talking about other people’s – unless you’re specifically bringing me in as a musicologist, and then I may require a higher fee because I have less incentive.Â

Start Your Day

…with a nice microtonal piano piece by Chris Vaisvil using the Pianoteq system tuned to a segment of the harmonic series. Pianoteq is supposedly the state of the art digital piano simulator; I had never bought it because at first it wasn’t fully retunable, but apparently that’s changed. Good news.