Some of you may recall the Consumers Guides, the full-page record review columns, that we used to run in the Village Voice. They may still do so, I haven’t looked in years. The format and its accompanying grading system were invented during the late medieval era by the Voice‘s dean of critics Bob Christgau; at least, so the legend was passed down to me by my forefathers, whose knowledge I would never presume to challenge. The grading system was intended to be unalterably strict. A B was the top grade for music that would be considered excellent only by fans of that genre. In order to get an A, a record was supposed to be “beyond category” (in Duke Ellington’s memorable phrase), music that would appeal even to people who didn’t usually listen to that genre. This was an impressively high bar. In other words, if something I reviewed was fantastic but would only appeal to new-music fans, the highest grade I was supposed to award it was a B-plus. A’s were reserved for new music broad enough in its appeal to cross boundaries. I was occasionally called on the carpet, gently, for grade inflation, for being too liberal with my A’s, because I couldn’t stomach giving a superb recording of a Cage chance piece, or a wonderful Niblock drone piece, a B just because its potential audience seemed limited. I fudged.

This category distinction was always something of an unwieldy fiction, because it presumed, especially in the case of new music, a specious link between excellence and accessibility. Strictly followed, it was likely to assign a B to a beautifully performed Milton Babbitt record, and a potential A to one of Steve’s Reich’s more mediocre pieces. Nor was it simply a new-music problem, since the most dynamite heavy metal album was still unlikely to find too many listeners outside fans of that genre. (I remember a small scandal when it was learned that a heavy metal fan in the production department had been quietly nudging the grades upward for metal albums after Christgau submitted them.) Even within one sub-genre, the line could be fluid. I think of Niblock as a hard sell for the average listener, but he’s got an occasional piece so transcendent, so clear in its effect, that I think almost anyone could be bowled over who really gave it a chance – as, sadly, few non-new-music fans were likely to do. That, one could argue, was the purpose of the A/B line, to mark off the truly amazing moments when the music burst beyond its premises.

I started remembering all this in connection with my recent post about literature. Were I a literary critic in this position, I presume I would have to give B-pluses to both Finnegans Wake and The Making of Americans, two books that I think are funny and wonderful and profound - neither of which, I have to admit, I’ve ever finished reading. One of my retirement plans is to read The Making of Americans out loud, which is how I fell in love with it, hearing it read publicly, and, I think, the only way to make it sink home or even make sense. I don’t have time in my life, obviously, for many books in this category. Not having to make my living via my literary expertise, I have the luxury of quitting novels that don’t fairly promptly engage my interest. I don’t mind having to think hard and figure things out, but if I’m going to do that the payoff better be ground-shiftingly transplendent and not held off until the last chapter, or I won’t still be there.

As someone who does make a living off my musical expertise, I have put the requisite brain power into a lot of esoteric works, some of which repaid the effort and some didn’t. I cherish a ton of music in the Voice‘s excellent-but-B-plus category. Maderna’s Grande Aulodia, Christian Wolff’s Snowdrop, Babbitt’s Vision and Prayer, Xenakis’s Bohor, Scelsi’s Fourth Quartet, Rochberg’s Sonata-Fantasia, Stefan Wolpe’s Enactments: these are not pieces that I’d give CDs of to my mother for Christmas, or play to impress non-musicians who come over for dinner, but I love them dearly and will listen to them when alone, even play them for students. In many cases I have inside information about how they’re written, which conditions the way I listen to them and helps me enjoy them more. Enactments, his three-piano piece that I digitized from vinyl this week, is Wolpe’s most austere and relentlessly abstract music, but I understand he used to watch fish in his fish tank to get inspiration for his playful jumps and darts, and I can hear the subtle surprises and twists he sets up, without quite being able to explain them in a way that a non-musician might grasp. On the other hand, there’s all the (equally) great new music I do play for guests and even at parties: David Garland’s songs, Paul Lansky’s Conversation Pieces, Ingram Marshall’s Evensongs, Beth Anderson’s Piano Concerto, anything by “Blue” Gene Tyranny, Elodie Lauten’s Waking in New York, Ben Neill’s Songs for Persephone, Mikel Rouse’s Living Inside Design and Love at Twenty, Duckworth’s Time Curve Preludes, Beglarian’s Five Things, Epstein’s Palindrome Variations, Lentz’s Wild Turkeys, and on and on and on – all that 1980s and ’90s “accessible” music that I suppose marks me as an old fogey at this point, but that most people have still never heard before and can very often be charmed with. Music that, when it comes on in the background, someone stops and says, “Ooh, what’s that? Can we hear it again from the beginning?” Music that I don’t particularly admire more than I do Vision and Prayer or Enactments, but that I could give an A to in a Consumers Guide with a cleaner conscience toward Christgau, because it does reach out to people who aren’t professional new-music mavens (the latter meaning composers, basically).

I think it was the American Mavericks website that had the inspired idea of dividing its listening streams into peanut-butter categories of “smooth” and “crunchy,” one for the accessible “new music” in the postminimalist 1970s sense, the other for more superficially off-putting fare. Of course, crunchy already divides into music that is complicated and multilayered (Carter, Ferneyhough) and music that may be far less structured but harsh and transgressive (Merzbow). Young people of a certain type in any generation will get excited about transgressive music, as separating them off from their parents and peers; I certainly went through such a phase, back when Stockhausen’s Mikrophonie I was about as far as crunchy went. The complicated-analysis style appeals to would-be know-it-alls, true elitists – though perhaps not only to those. In reality, “crunchy” does not guarantee profound anymore than “smooth” guarantees simplistic. “Venus” from my Planets is my most oft-downloaded mp3, with hundreds of hits a month lately; it’s smooth as hell, and I grin to think of all the people who listen without registering the layering of 3/4 and 25/16 meters that runs through it. Postclassic Radio, back when I had it running, was about 96% smooth, and to that extent not fully representative of the wide range of new music I admire. Seduction was the intent.

Grades are silly, and I hope no one was ever fooled (or insulted) by the Consumers Guide categories, but it is interesting to imagine grading pieces not mostly on quality, but on a multidimensional spectrum of opposites with no value judgments attached to either side:

- smooth vs. crunchy

- original vs. traditional

- simple vs. complex

- meditative vs. exciting

- carefully crafted vs. messy

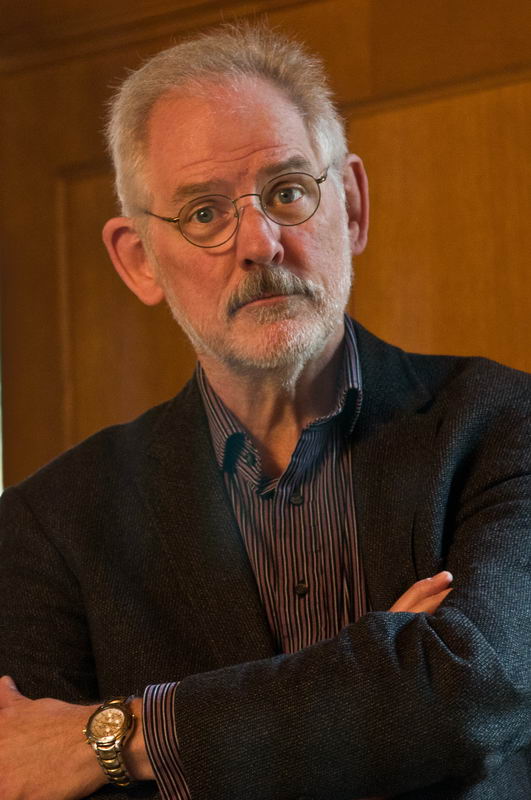

And then with an evaluation thrown in at the end, where Virgil Thomson thought it should be if included at all. Not that pieces of music can be summed up by their generic attributes, as the Pandora people would encourage us to think, but correlating the evaluation to the other sliding scales might reveal more about the biases of the person doing the evaluating. Of those above, my strongest preference leans toward meditative rather than exciting. I often call myself a devotee of the “slow, boring, depressive” aesthetic, and occasionally someone of similar tastes (Feldman, Harold Budd, Eliane Radigue) responds with a twinkle and a nod because they know exactly what I mean. Boring, much as I love it, can be just as effective as transgressively crunchy at relegating music to that B-plus, specialists-only arena.

So this A/B line maps on to my divided consciousness as a composer/critic/reader. I’m glad that crunchy music is out there, but I’m not likely to write any. I want my music on the potential A list for reasons of both personal vanity and ethics. I want my music to grab the listener the way the novels I reread grab me. Maybe I grew up weird enough as a child and just want to be liked, or, as I suspect, perhaps I’m a historical relic of the “accessible” new-music boom of 1977-83, a living fossil conditioned by the ambience of his formative years. I’m happy that my analytical knowledge allows me to listen sympathetically to a lot of music that’s opaque to novices, but I would feel glum if I had to explain about the 3/4 vs. 25/16 before someone could enjoy listening to “Venus” – feel like I’d only half done my job, in fact. A tension between innovation and populism runs through my entire output, and I feel a little guilty when innovation wins. I do not disapprove, either in music or literature, of all that thorny art praised by the elites. Someone’s got to see how far out we can go and still bring something back. As a musicologist I’ll take time to study all the music, no matter how rarefied. As a reader, I’m happy to leave certain reputedly forbidding novels to the experts, unless I get a strong recommendation from someone who similarly has no axe to grind. As a composer, I never want to be relegated to the B-pluses because I didn’t take the time to appeal to more than the experts.