My partner in minimalist conference-running David McIntire actually went to San Francisco and visited the elusive Dennis Johnson this week, composer of the five-hour piano piece November and gaining quite a belated reputation recently as a minimalist pioneer. Dennis is self-admittedly dealing with the early stages of Alzheimer’s, but he staves it off via physical exercise and took our musicologist friend on quite a hike. Turns out Dennis was born November 22, 1938, so we have that now for the reference works; and David saw some music, without enough context to make sense of it yet. On a clear day Dennis can see the Golden Gate Bridge from his apartment, and David sent me a few photos of him. I can’t think now why I had pictured him as tall and heavy-set:

C’est un faux pas vrai, mais non?

Nicolas Horvath, the French pianist who commissioned my homage-to-Philip-Glass piano piece Going to Bed, is finally giving the piece its long-delayed European premiere. It’s part of an all-night program, June 27-28, titled First French Night of Minimal Piano Music, way at the very end, at the Protestant Temple in Collioure in southern France. Looks heavenly. France is not a country I would have expected to pick up on my music, but I’ve had several performances there in recent years – perhaps significantly, none in Paris.

My piece is based on the chord sequence from the “Bed” scene from Einstein on the Beach. I probably should have given more thought to the title. I sent a copy of the piece to a woman pianist of my acquaintance. A couple of months later I ran into her, and she reeled off, as I waxed in silent impatience, a list of new pieces she was about to play on an upcoming concert, none of them written by myself. At last she paused, and, after a decent moment, I blurted out, “So, how about Going to Bed?” I studied the dubious look on her face for a full five seconds before it dawned on me what I’d said. We were not in a private situation.

Call it a Freudian slip, but I think most male composers over a certain age (say, 40 at most) will vouch for me that, given a choice between getting laid and a highly visible premiere, at this point we’ll take the premiere.

Saving Music from False Consciousness

Many of you were invigorated by my colleague John Halle’s provocative article “Occupy Wall Street, Composers and the Plutocracy”, which I posted in this space last year. He’s now written a kind of historical prequel, tracing the changing relationship between music and leftist politics through the 20th century: “‘Nothing is Too Good for the Working Class’: Classical Music, the High Arts and Workers’ Culture.” I find particularly intriguing a mid-century view articulated by Hanns Eisler that “simple music does and can reflect only simple political thinking,” and that “it is easier for people who appreciate complex music to move on to an appreciation of complex political problems, than for those who limit themselves to folk (pop, rock, gospel, blues, etc.)†This will certainly not go unchallenged (and John is not asserting it as his own view), but I’m fascinated that, before the 1960s fusion of rock and progressive politics, classical music was seen by some as having a potentially more crucial role. The depth of John’s historical knowledge in this area, and – even more – his ability to maintain all these cultural contradictions in their complexity, is phenomenal. We’re actually discussing writing a book together, though I’m not sure what, beyond my 600-word-an-hour writing speed, I have to contribute.

End of the World 7.0

I am perhaps a little overly susceptible to end-of-the-world scenarios, despite having lived through a few that came to nothing. But I’m a little freaked out about this, and hope that someone knows more than I do.

My laptop went dysfunctional from a rare condition two weeks ago – the screen simply went blank and would no longer transmit light, though happily the hard drive, logic board, and desktop remain operational. When I considered the possibility of buying a new laptop (the ill one is less than two years old), I was warned that I would have to get a Mac with OS 10.7 or 10.8, namely (if not respectively) Lion or Mountain Lion. Two computer repairmen, one of whom I’ve been going to for many years, told me that many people (including even accountants) buy a Lion or Mountain Lion Mac, and then find that virtually none of their software works on it. Apparently much of the professional software used by specialists in various disciplines is not updatable, or not being updated, for these operating systems, which, following the lowest common denominator, are being designed only for the most generic programs. I know this particularly affects my microtonal software such as Li’l Miss Scale Oven, which forms the basis of much of my career. My trusty computer guy told me, “I’m afraid we may be coming to the end of the personal computer as we know it, and that what we’re going to have instead is an appliance.” Boy, did he say that word with a sneer. The other guy told me that if anyone suggests 10.7 or 10.8, “Look them in the eye and respond: ‘Over. My. Dead. Body.'”

Is anyone on this? It became apparent that, no matter what my laptop repairs cost, I have to keep that machine alive for as many years as possible. Buying a new computer may no longer be an option. Both computer guys tell me they spend a lot of time reinstalling Snow Leopard for people who tried the higher OS’s and lost everything. Is this mainly a Mac problem? Is there a counter movement in place anywhere? Are we all doomed, doomed, I tell you?

Fitting Homage

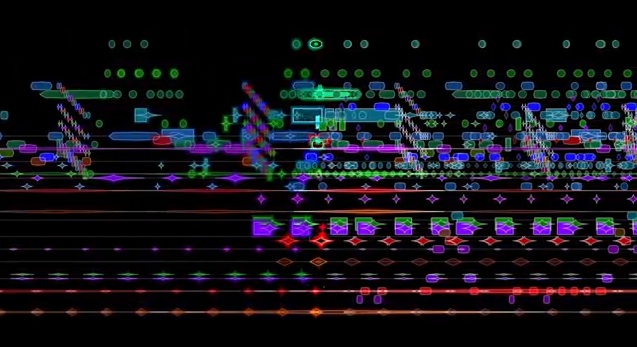

The kindly editors of Ashgate Press are scurrying to cross all the final t’s and dot the i’s of The Ashgate Research Companion to Minimalist and Postminimalist Music, with the expeditious assistance of the book’s three editors, Keith Potter, Pwyll Ap Sion, and myself. The goal is to have it published and available by October, to sell at a special price to the attendees of the Fourth International Conference on Minimalist Music in Long Beach. (The regular price, I understand, will be around $150; it’s one of Ashgate’s hefty, library-aimed tomes, with articles by twenty authors.) We had a devil of a time coming up with cover art because we didn’t want to privilege any of the Super Four – Young, Riley, Reich, Glass – over the other three, but Pwyll came up with some wonderful graphic charts of early minimalist pieces by Jon Gibson, who had worked with all four of them, and they’re attractive and set the perfect tone. And now I have just learned that, thanks to another of Pwyll’s inspirations, the volume will be dedicated to William Duckworth, in memoriam.

The kindly editors of Ashgate Press are scurrying to cross all the final t’s and dot the i’s of The Ashgate Research Companion to Minimalist and Postminimalist Music, with the expeditious assistance of the book’s three editors, Keith Potter, Pwyll Ap Sion, and myself. The goal is to have it published and available by October, to sell at a special price to the attendees of the Fourth International Conference on Minimalist Music in Long Beach. (The regular price, I understand, will be around $150; it’s one of Ashgate’s hefty, library-aimed tomes, with articles by twenty authors.) We had a devil of a time coming up with cover art because we didn’t want to privilege any of the Super Four – Young, Riley, Reich, Glass – over the other three, but Pwyll came up with some wonderful graphic charts of early minimalist pieces by Jon Gibson, who had worked with all four of them, and they’re attractive and set the perfect tone. And now I have just learned that, thanks to another of Pwyll’s inspirations, the volume will be dedicated to William Duckworth, in memoriam.

Every once in awhile the universe falls into alignment, and a bit of perfect justice is done on earth.

Time-Keeper and Track-Skipper

What an unexpected pleasure to see New Music Box absolutely dominated this weekend by my long-time comrade-in-arms Robert Carl – unexpected because, though we’ve been trading e-mails lately, he never mentioned it was coming up. Two Chicago grad students who managed to get East Coast teaching jobs within a couple of hours of each other, Robert and I have been talking regularly for more than thirty years. I used to think we were from different sides of the tracks, but actually Robert skips all over the tracks. I believe I once described him as half Uptown and half Downtown with no touch of Midtown. His rock-solid sense of composer priorities and politics has always served as a reality check for me, so if you think I’m off-the-wall, you can thank Robert that I’m not even more completely unhinged. He’s been a moderating influence, and an inspiration.

Waiting for the Next Revolution (or Did I Miss it?)

A few months ago electronic composer Nic Collins sent out a heartfelt questionnaire to several of his new-music maven friends. (I should say, I don’t know whether “electronic composer” is still a meaningful term, but I’ll qualify it by adding that Collins makes the most touching and humanistic examples of electronically-produced music I’ve ever heard.) Nic was having a kind of intellectual crisis due to his perception that there was no aesthetic revolution going on among his students comparable to the Cage/sound art/minimalism revolution of the 1960s and ’70s – or at least, that there had been no new movement with a series of groundbreaking works that his students could be as energized by as he had been. Since the 1970s, he wrote, “I have continued to hear great new pieces, but I have detected no shift in the fundamental terrain of music that rivals the magnitude of the changes that took place in the 60s and 70s. I find this admission more than a little depressing.” And he was afraid of falling into the pattern described by Douglas Adams (which I’d never read before, but I see has made its way around the internet):

“Anything that is in the world when you’re born is normal and ordinary and is just a natural part of the way the world works. Anything that’s invented between when you’re fifteen and thirty-five is new and exciting and revolutionary and you can probably get a career in it. Anything invented after you’re thirty-five is against the natural order of things.†(The Salmon of Doubt, 2002.)*

(I’ve been sharing this quotation with my students, and it makes them look thoughtful.)

Anyway, many people responded to Nic’s questions, myself included (it was February when I was in Miami with nothing to do for the afternoon, so I quickly wrote him a long screed). He promised to make public his summary of our responses, some consolatory, some casting his original premise into doubt, and has now done so as the article “Quicksand” (PDF) on his web site. It’s worth reading.

*I have always loved a similar saying attributed to George Bernard Shaw: “I never dared be radical when young for fear I would become conservative when old.”

Disproportionate Reactions

Here I am, the third-string composition teacher at a small undergraduate college. I write uncontroversial, peer-reviewed books about Nancarrow, Cage, Ashley, Ives, three of whom are dead. I never sit on the Guggenheim committee, the Fromm commission committee, the Pulitzer committee, and I can count the prize committees I’ve been on with less than one hand: the Grawemeyer one year, and no one I voted for won; the Herb Alpert Award about ten years ago; and the ASCAP Young Composer Awards about 18 years ago. I used to be a music critic and have some influence over people’s careers, but that was years ago, and I closed up my dwindling shop in 2005. I’m in two small musicological organizations, the Charles Ives Society and the Society for Minimalist Music, neither of which plays any role in the composition world, and in neither of which I wield any power. I amuse myself by restoring the occasional forgotten composition to the repertoire. My music isn’t played often. The only current outlet for my opinions is this blog, which has been mostly inactive these many months. In short, if you listed all the people who have power over what happens in the world of new-music composition and performance, you would list hundreds and hundreds of people before you came to me, if indeed you ever did.

My views on composition are heterodox and far outside the mainstream of what most composers believe these days. And yet when I express those views, some people become absolutely livid and write in to damn me and tell me what a horrible person I am, expending tremendous emotional energy as if I must be stopped at all costs. People gather at composers’ web sites to bewail my pernicious opinions. And the only possible explanation I can think of, that makes any sense, is that I am hitting a nerve – that I am telling a truth that someone doesn’t want to think about. Because unless I am persuasive solely because I am right, why would anybody in the world give a damn what I think?

UPDATE: One thing that no one has mentioned about my nefarious academic/professional post, which has some people clutching their pearls, is that I gave the new-music community a free lesson in how to write more effectively. No one thanks me (well, one commenter slyly alluded to it), but I bet that some of the people who think I’m the Snidely Whiplash of composition will not be too proud to avail themselves of my suggestions. I hope so, I’d like to see more fluent writing in the new-music discourse.

You’re welcome.

A Rite of Passage

I noticed about a year ago that the centennial of Le Sacre du Printemps was coming up fast, and I wondered if a big deal would be made about it – of course, the interest has been immense. Amazing to think that a piece that still sounded so revolutionary when I was a kid is now passing into the category of history-more-than-a-century-old. I don’t know of a better convenient way to celebrate the anniversary tomorrow than by watching Stephen Malinowski’s elegant videos of the entire MIDI information here: Part I and Part II.

What Writing Has Taught Me about Composing

Daniel Felsenfeld asks, as someone does occasionally, what is wrong with being an academic composer. I’m tempted to say, if you have to ask, then you won’t understand the answer; but let me try a new tack.

My wife is a professional arts administrator; she started out at the St. Nicholas Theatre in Chicago, founded by David Mamet. She’s back in professional theater again now, but in-between she spent quite a few years presenting theater, dance, and music in academia. Her academic colleagues didn’t always appreciate why she was such a stickler for centralizing box office functions, training ushers, restricting stage access before a performance, getting the stage lights just right for a concert, and things like that. She seemed to be too much of a perfectionist in details that didn’t matter much from the presenter’s point of view. The reason was always that she wasn’t only looking from the presenter’s point of view: she knew how the theater experience looked and felt from the audience member’s seat, and what backstage rigor it took to give the subscriber a smooth, pleasant experience with no irritations to distract from the stage art. Watching her career and its occasional frustrations, I learned that academics knew how to put on a show, but they weren’t terribly concerned with what kind of overall experience the audience had. As long as everything went right onstage, the audience was just supposed to show up, find their parking spot and seat as best they could, and marvel at what was placed before them.

Likewise, I am a professional writer; but I am an academic lecturer. My lectures may sometimes be remarkable for their content, but rarely for their form or presentation. I am not a stirring orator, I do not hold an audience spellbound. I often have to correct myself, and add in information that I should have presented earlier. I mumble, struggle for words, and say, “ummm….†It’s acceptable because it is my students’ responsibility to show up, pay attention, ask questions when they don’t understand, and glean what information they need from my rather slipshod recitation. Oh, I’m humorous and energetic, and I’ve developed some tricks; I can tell when my students’ attention is flagging, and I drop in jokes and distractions to push the refresh button. But no one not vitally interested in my area of research would come hear me lecture just for a thrill. I wish I were an awesome lecturer, because I end up doing it occasionally, and I’m sure I could have become one had I gotten some training, had a professional lecturer give me tips and feedback and criticism. It never happened, because I’ve never had to depend on public lecturing for a living.

But writing was my sole living for many years, and my paycheck depended on my cascades of words being irresistible. The great schooling of my life was my first seven years at the Village Voice: editor Doug Simmons spent 90 minutes a week with me going over every sentence of my 950- or 1700-word column, sharpening the expression, clearing ambiguities, unblocking metaphors, changing the order of paragraphs to anticipate questions that whatever I said might raise in the reader’s mind. My medium, the process made clear to me, was not only words, but the psychology of the reader’s attention, which was fairly predictable, and which I had to learn how to navigate. It was my job to grab people’s attention with the first paragraph, and to keep them reading to the end.

For instance, look at my previous blog entry, on the Ives symphonies. Every paragraph after the first begins with a transitional phrase, usually one that picks up the topic from the previous paragraph and recasts it in a new light:

“What seems most indicative of a superficial view of Ives, though…â€

“And so on and so forth for many pages,…â€

“More importantly, the Ives First has held up very well…â€

“That this has been so little acknowledged is a symptom…â€

“The truth is that both of these stories are true.â€

“Ives himself contributed to the problem.â€

“But we, who ought to know better, are forced to choose…â€

“It is not so rare.â€

I can write for pages and pages like this, never once beginning a paragraph without a link from its predecessor to keep the reader reading. I do this consciously, or more accurately semi-consciously, because I am trained to do it. In my 4’33†book, which was intended for a more general audience than most of my writings, I even adopted the time-honored technique of using the final sentence of a chapter to pique interest in the subsequent chapter:

“Cage had summed up his life’s work to date: the percussion music, the rhythmic structures, the prepared piano… and it was time to move on to something new.â€

“Cage – and who would be surprised by this? – wrote 4’33†very quickly. And then headed to Woodstock and braced for the response.â€

Many people have told me that they read the 4’33†book in one sitting, which confirms for me that I knew what I was doing. I knew how to keep them reading. It’s a smooth read. One technique I use, when the venue is important enough, is to read my text to myself out loud, because my ear will pick up infelicities that my eye and brain miss. On a reread, I replace colorless words like “flow†and “smooth†with “cascade,†“irresistible,†and so on. I vary my sentence length. My general tendency is toward long sentences, but every now and then I throw in a short declarative sentence, or a series of them, and it’s amazing how much that energizes the text. It just works. (See?)

And I emphasize: I was not born writing this way, nor did I learn it by trial and error. I sometimes get credit for being profound, when it’s really that I’m simply well-trained to make my points clearly and colorfully.

Note that my professional tricks do not limit what I want to say. Quite the contrary. I write a lot of things that are counterintuitive or against the conventional wisdom, and I can make them seem inevitable by concealing my motivation until I’ve led the reader down a thought-path that can lead nowhere else. I am not a lesser or more superficial writer because I know how to keep the reader engaged, although academics often assume I must be. I do not have to tell the reader only what he wants or expects to hear to achieve my goal of getting them to read the entire article or book, and digest information that might never have occurred to them before. After setting down in draft the information I want to convey, I apply a lot of technique just drawing the reader through the article, and you know what? It doesn’t cheapen what I’m saying. In fact, as the prose grows more lapidary, my own thought grows clearer to me as well. The urge toward readability leads to clarity and truth.

In a moment I’m going to draw a metaphor between writing and composing, and I’ll let you start imagining it.

From these observations one could draw a definitional distinction between the academic and the professional. The academic is concerned only with content, not with presentation. The academic is not concerned with the reader’s or listener’s or viewer’s experience. The academic does not think about the audience’s psychology, and consoles himself with the specious platitude that everyone is psychologically different, and that he couldn’t predict it anyway. The academic thinks only of his own genius, or his data, and leaves the reader or auditor to puzzle out his meaning in painstaking and often repetitive reading or audition. The professional, however, puts himself in the reader’s place, and observes how the order of the information, his transitions, his emphases, the pacing and preparation of his surprises, leads the reader or listener into fairly predictable reactions. The professional shows the audience member where to focus, and does so with a backgrounded technique which seems effortless. The reader, reading a pro, is not aware of how the pro pricks and sustains his attention; he’s just curious to keep reading.

I don’t think I’ve yet said anything that should be controversial, but when we extend this analogy into the writing of music, hackles will rise. By our argument, the professional composer would be one who knows how to keep the listener engaged in the piece. Haydn or Mozart, both pros whose livelihood hinged on their musical entertainingness, will conceal a motive from the main theme in a slow introduction or subsidiary line, and when it emerges in the main theme, that theme will seem exactly right without our knowing why. Motive leads to motive, phrase to phrase, in a deceptively effortless way (Mozart’s “artless artâ€) that draws our attention along. In highly logical music we want to hear what happens next; in sensuously gratifying music, we are content if the nuances sustain the pleasure without interrupting it. Professional music grabs the listener’s attention and knows how to hold on to it.

What happens in academic music I need hardly spell out, we all know the trope so well: the composer bases a second idea on the same pitch set as the first, and though we can’t make the connection by ear, we’re just supposed to assume that the composer is a genius and knew what he was doing. The composer crafts a structure (Elliott Carter’s 175-against-216 structural polyrhythm in the Night Fantasies comes to mind, though any concrete example will rouse academic defenders) that looks elegant on paper, though the effect on the listening experience is nil. Or, more often these days, the composer builds a long and plausible tension-and-release form, but doesn’t put in the music any catchy images for the listener to care about, or foreground for the listener the musical ideas underlying the seemingly unmotivated angst.

This may seem like a straw-man argument, but there is plenty of evidence that this straw man walks and procreates. One need only read the indignant posts on composer web pages whenever such an idea is broached: “Well, you have to listen to the piece more than once.†“I can’t water down my music for people who aren’t versed in modern music!†“Of course if you can’t follow Schoenberg’s music, you’ll never follow what I’m doing.†“It’s self-indulgent to write attractive music just because audiences like it.†“I can only write for myself.” And so on and so on. I remember the late James Tenney, whom I admired in so many ways, saying, “I can’t think about the listener, because there is no such thing as the listener. Everyone listens differently.†(It reminds me of Margaret Thatcher’s “There is no such thing as society, there are only individuals,†equally intended to let the speaker’s conscience off the hook.) That a composer can’t think about the listener, or even shouldn’t because it leads him away from his lofty purity, is one of the field’s most widely aped platitudes.

One advantage of the definition I’ve spelled out here, I think, is that it makes very clear what the relation is between writing academic music and working in academia. Strictly speaking, there need be no link at all. It should be as possible for a professional composer to teach in a university as it is for me to continue being a professional writer while in a music department, which I do. But, as my wife’s experience has demonstrated, academics are unlikely to thank you for being professional. There is little incentive in the structure of academia to make work with the audience in mind, since the audience is mostly captive, the economics non-profit. The professors are the insiders, the privileged, the credentialed, and the audience is on its own. In fact, when my professional writing is “peer-reviewed†by academics, they slap me on the wrist for being too “breezy,†“journalistic,†and “colloquial†– they try to bring my professional standards down to their academic ones. This year I was secretary for the faculty senate, and my colleagues always had to tone down my minutes from each meeting to make them less distinctive. Academia fears communication that is too vivid and direct; clarity invites argument. And I guess that’s fine in the social sciences and other “real†academic disciplines: they’re writing for each other, and have a professional incentive to painstakingly navigate each others’ coagulated prose. (Still, look at Paul Krugman, whose trenchant writing style has clarified modern economics to an entire generation of lay readers.) But the artist, however academically trained, is not writing for fellow professionals, but for the wider world – there’s the difference.

In other words, working in academia will not make you academic, but to remain professional within academia you have to go against the flow and brace yourself to not be appreciated. The rewards given in academia do not require professionalism, and in some cases even discourage it.

Now, I am obviously not a professional composer in the sense that I make a living off my music and it has to be really good for me to get paid. Almost no one is. What we usually mean these days by a “professional composer,†and the meaning I have elsewhere used in this blog, is someone who can play the prize circuit, network well, and get commissions. The process has almost nothing to do with audience reaction; with occasional exceptions like Glass and Reich, most “big-name composers†are associated with an idiom that attracts a tiny audience at best. But in this professional-versus-academic sense I still try to keep – with my well-trained writer’s ear as a model – a professional attitude when I write music. I repeat catchy and identifiable riffs. I sometimes, even microtonally, play off of a harmonic background with predictable resolutions. I embed common melodic archetypes to guide the ear through my wild polyrhythmic schemes. I listen to each new passage dozens of times to make sure everything seems internally motivated, and I revise heavily. I constantly tell my composition students that their medium is not merely notes or sounds, but the listener’s psychology. I’m continually pointing out what their music leads the listener to expect, and tell them that they either have to gratify that expectation, or clearly deny it in favor of something even better that works on a larger level – but they can’t simply ignore expectations that they’ve created. They resist, and the academic music that surrounds them is full of enticing poor models.

And note that my professional tricks do not limit what I want to say in my music. I write a lot of things that are counterintuitive or against any conventional idiom, and I think I make them make sense. I hold that I am not a lesser or more superficial composer because I know how to keep the listener engaged, although academics often assume I must be. I do not have to give the listener only what he wants or expects to hear to achieve my goal of getting them to listen to an entire, often rather bizarre piece. I apply a lot of technique just drawing the listener through the piece, and it doesn’t cheapen the music, though my academic colleagues sometimes claim it does. My anecdotal confirmation is that complete strangers have come up to me at intermission to say how much they enjoyed the music, and I’ve seen audience members cry during my more intense choral pieces. Our 84-year-old department secretary, long inured to contemporary music that just seemed weird to her, was thrilled that my piano concerto was so much fun to listen to; and that delighted me more than an official prize would have. The academic composing community does not reward me, but I’ve sometimes gotten my reward from watching the audience. (And often from reviews: as someone wrote of Nude Rolling Down an Escalator, “Though all the pieces are fiendishly and impossibly complex, they are also easy to listen to….”)

Remember what Feldman said about the academic composers of his generation: “They have brought the musical culture of an entire nation down to an undergraduate level.†In the arts, the professional is a higher and more difficult standard to meet than the academic. An academic education is preliminary to professional experience – but it is not the final step.

Ives, Caught Between Two Caricatures

Conductor Leonard Slatkin is conducting all four of Charles Ives’s numbered symphonies in New York tonight. Good for him. Wish I could be there. It’s kind of too bad, then, that he marred the occasion by writing a rather condescending article about the works for New Music Box, with undue but apparently characteristic emphasis on how much he hated Ives’s music when he first heard it. I myself found Mahler’s symphonies overblown and too grandiosely emotional when I first heard them at 17, but I’ve been musically mature for quite awhile now and I don’t preface all my comments about Mahler by trumpeting my embarrassing adolescent imperceptiveness. But Slatkin’s strategy seems to be to assume that, of course, we in the classical music world [whaddaya mean we, paleface?] look down our nose at Ives, him being an amateur and all, but actually, when you give him a chance, he’s much better than he seems, right?

What seems most indicative of a superficial view of Ives, though, is Slatkin’s casual and highly clichéd dismissal of the First Symphony:

The First Symphony is a naïve exercise, a work from Ives’s student days under Horatio Parker. The music is mostly derivative, sounding sometimes like Dvořák, Tchaikovsky, and Brahms, with a bit of Wagner thrown in for good measure. There is little to identify that we would call “Ivesian.†The opening of the slow movement, with a plaintive English horn solo over the strings, is clearly a crib of the “New World†Symphony… The piece emerges as that of a talented fledgling who has not yet found his voice.

Ives wrote much of the First Symphony during his last year at Yale, and it strikes me as the least naive piece ever written by a college senior. With no strong American models to work from (I keep trying to like the Chadwick, Paine, and Bristow symphonies, but it’s always kind of a mercy listening), young Ives quite brilliantly studied Tchaikovsky’s Pathetique, Beethoven’s Ninth, and especially Dvorak’s New World symphonies as models. Peter Burkholder has laid out in detail what Ives gleaned from those works, and as he says in All Made of Tunes: Charles Ives and the Uses of Musical Borrowing, “Seldom does a passage truly sound like another composer.” Ives did indeed model his second movement in particular after Dvorak, but here’s how Burkholder describes it:

Yet Ives carefully differentiates his melody from its source. He avoids the dotted rhythm that pervades the Dvorak while creating a new motive in m. 2 and repeating it in inversion in m. 4. This motive propels the melody through the high and low points of the line, where Dvorak allows a break between melodic units… The pitch material that Ives omits… is both highly recognizable as part of Dvorak’s melody and melodically somewhat repetitive, stressing the same pitches as the surrounding music. Leaving out these elements tightens the melody and makes it more Ives’s own…

Taken as a whole, Ives’s theme is an elegant condensation of Dvorak’s, which is three times as long. Dvorak’s melody is a tiny ternary form (ABA’) with repetitions in each phrase; in the Ives, nothing essential is missing, but most repetitions within and between phrases are trimmed…

Comparing Ives’s theme with Dvorak’s shows both how similar and how different they are. This movement represents an act of homage to one of the great modern symphonists, but it is also a challenge, declaring that Ives is not afraid to compete with Dvorak on his own turf. Recognizing that Dvorak’s theme is an elegant and famous tune, Ives cites it and tries to improve on it… (pp. 91-93)

And so on and so forth for many pages, showing how Ives taught himself to write a symphony by studying successful models, but not accepting them uncritically, and coming up with his own improvements where possible. This is not naive composing, the hopeful appropriation of the general sound of a more-famous composer. I wish some of my students had the mental fortitude and determination to so closely study works by other composers they admire, steal what they can and try to make their own music even better, more effective, and tighter than their models.

More importantly, the Ives First has held up very well for me over the last forty-five years, and regularly surprises me with how much I enjoy listening to it. Beyond that, I find it distinctly Ivesian. In his conventionally romantic music Ives often (as at the beginning of the first movement) had a characteristic way of modulating almost constantly, yet never leaving the ear in doubt at any particular moment what key is implied. Unlike so many of the late romantics like Reger, Scriabin, early Schoenberg, there is hardly ever the kind of tonal ambiguity that comes from slipping into and out of diminished and half-diminished seventh chords. Instead the music frankly moves from key to key almost measure by measure via a smooth use of pivot tones. This kind of tonal technique can also be found in the Busoni Piano Concerto (a 1905 work Ives surely never heard), but in none of the composers Ives was using as models. He owned it. His teacher Horatio Parker specifically complained about Ives “hogging all the keys at one meal,” a patent sign that student Ives was doing something in his conventionally tonal music that the German-educated Parker hadn’t seen before. This relentless yet smooth modulating technique runs from the First String Quartet up through Ives’s Second and Third Symphonies as well, and was clearly a permanent fixture of his own, personal version of Romantic musical rhetoric.

That this has been so little acknowledged is a symptom of how difficult it has been for the pig-headed classical music world to bring Ives into focus. The first version of Ives’s reputation came from Henry Cowell: he was a thoroughgoing experimentalist, seemingly self-taught (or taught only by his father), one who invented tone clusters, polyrhythms, and many other techniques that Europeans would later discover. The musicologists seemed to hate the idea of this outsider coming from nowhere, and in the late 1980s they launched their revisionist attack. Ives learned more from Parker than he admitted, they wrote; he knew Debussy’s music, quoted it, he studied lots of great classical pieces and applied what they learned from them. The revisionist Ivesians seem to rebel against the notion that Ives ever had an original idea in his life. One exemplary article compares a page from Liszt’s Sonata with one from the Concord with the aim of showing how identical they are – and I’ve never in my life seen any two pages of piano music look more different.

The truth is that both of these stories are true. Charles Ives had not two careers, but three: successful insurance executive, ground-breaking experimental composer, and brilliant composer of symphonies and songs in the European Romantic tradition. We know that Ives’s experimental interests and tendencies emerged already in high school, but when he went to college he applied himself with vigor to a traditional education and learned to write the conventional way, very, very well. I love Ives’s conventional works just as much as I love his most outrageous collages, satires, and atonal structuralist experiments – and I see little support for this position in the discourse on Ives, academic or otherwise. My favorite Ives work, swear to the gods, is his Third Symphony, which is thoroughly Romantic as to form and tonality, yet straddles the experimental here and there with its shadow lines and hidden quotations. (I’ve written a playable piano transcription of the Third which I hope someone will perform someday – PDF available to anyone interested.)

Ives himself contributed to the problem. In the 1920s, after he found men like Cowell, Ruggles, Milhaud, Varese, and others who were championing modernism, he began to disparage his more conventional music, calling the first three symphonies and one of the violin sonatas “weak sisters.” That’s really too bad, but entirely understandable in the new milieu in which he was trying to break out of his long-standing and undoubtedly frustrating isolation. Even so – and I find it one of the most revealingly poignant footnotes in Ives’s long life – when he entered a recording studio on May 11, 1938, to record some of his piano music to let the world know how it was supposed to go, he played two of the Emerson Transcriptions, several abstract piano studies including the thorny Anti-Abolitionist Riots – and the original version of the slow movement of his First Symphony that Parker had rejected. Imagine this 63-year-old, cranky, diabetic man, finally riding the crest of modernism and getting some recognition, and he sits down and plays the Largo he wrote in college that was better, he was convinced, than the version his composition teacher made him write as a more conventional substitute, because the original modulated too much. Forty years later he still had that Dvorak-inspired movement in his hands, his head, and his heart. He was not going to let Parker get the last word. That music meant more to Ives than he could let on later in life.

But we, who ought to know better, are forced to choose between two stereotypes of Ives. Slatkin, typifying the admirers of Ives the experimentalist, says there was nothing Ivesian in the First Symphony, that he hadn’t found his voice. For those people, the Fourth Symphony is the greatest by far, really the only important one. For the revisionist musicologists, Ives simply grafted himself onto the European tradition, and his wildest ideas all seemed to have had European precedents, merely Liszt and Scriabin (several of whose sonatas Ives owned scores of) taken to their logical conclusion. As a teenager I discovered all the symphonies at the same time as the Concord and First Sonatas. I would never have dreamed of claiming that Ives wasn’t steeped in the European music literature; he knew the Romantic syntax exquisitely, and developed his own smart, individual way of handling it. And I equally would never have denied that many, many of Ives’s ideas came out of his own head, and had never before been found in any music he had heard.

It is not so rare. Henry Cowell likewise wrote strange, unearthly works for the inside of the piano and relatively conventional symphonies. Lou Harrison could swerve among a Brahmsian style for his piano concerto, a Balinese style for his gamelan works, and a spiky modernism for his Third Piano Sonata. I myself have written strange microtonal works, some jazz tunes, and, in my Transcendental Sonnets, a movement based on William Billings’s style and another modeled on Brahms’s Requiem. These are polystylistic times, and many of us are multilingual; Ives simply seemed to be the first. We need to get over the two simplistic pictures that Ives’s “real” works were his complex atonal ones, and the early ones are of merely anecdotal interest; or that he was “really” just an extension of European late Romanticism, and his innovations are of minor importance. The times and situation, and his own inner urgings, demanded that he be bilingual, and he spoke both languages – the one he learned, and the one he invented – fluently.

You Weren’t Doing Anything This Evening Anyway

Sorabji enthusiast David Carter has given me a link to Jonathan Powell’s world premiere performance of Sorabji’s Sequentia Cyclica Super Dies Irae Ex Missa Pro Defunctis (1948-9) – at seven hours, apparently Sorabji’s longest, and some say greatest, work. [UPDATE: Oops – Sorabji’s Symphonic Variations for piano (1935-7) is nine hours long, so not true.] (After you click the play icon, don’t be put off by the brief orchestral passage that announces the show.) It is indeed magnificent and exhausting.

UPDATE: David warned me that the piece was incomplete, and indeed variations 7 and 11 are missing. But the remainder is still seven hours long. The playlist given seems to suggest that several variations are missing, but it’s only those two. Variation 22 is a 78-minute passacaglia, and the final variation, #27, is an hour-long quintuple fugue. You really going to miss variations 7 and 11?

Dull Life, Interesting Omission

This time of year I am always preoccupied with getting the students whose senior projects I supervise graduated, and though I am teaching less, I have more seniors (six) than usual (one to three is what most Bard faculty have). In addition to that, this year for the first time, as chair of the arts division I am trying to corral our arts faculty into all the necessary committee slots for next year. The number of committee positions that require tenured faculty is just barely smaller than the number of tenured faculty, and so what with the normal run of sabbaticals and leaves of absence, it takes weeks of strategizing and negotiating to satisfy the demands of the faculty handbook; the dreaded faculty evaluation committee I still have yet to work out (and why it’s so dreaded is beyond me; as a former critic I guess I’ve never blinked at evaluating my peers). As at most schools these days, Bard’s untenured-to-tenured professor ratio seems to creep upward annually, especially in the arts, and the administrative squeeze gets ever tighter.

All this is to explain how I missed commenting on the world premiere of one of my compositions last night. The Eclipse Quartet played Love Scene, my just-intonation string quartet, at Microfest 2013 in Pasadena. The title comes from the fact that the piece is a string quartet version of a brief romantic scene from my as-yet-unperformed microtonal opera The Watermelon Cargo. The piece is ten years old now, and I am grateful to John Schneider for finally getting it a hearing, and to the Eclipse ladies for playing it. I had been looking forward to it, but I was heavily responsible for a complicated senior concert this week, and May 4 came and went before I noticed the calendar. I forget these days that I am, or was, a composer.