One of my student composers was talking today about wanting to write a really simple unpitched percussion piece. I told him about Mary Ellen Childs’s piece Click, for three people playing merely claves in incredibly detailed choreography, which was one of the wildest and most enjoyable performances I ever reviewed for the Village Voice. We looked, and naturally it’s on Vimeo. It’s a total classic, a postminimalist paradigm, up there with Piano Phase and Music in Fifths.

One of my student composers was talking today about wanting to write a really simple unpitched percussion piece. I told him about Mary Ellen Childs’s piece Click, for three people playing merely claves in incredibly detailed choreography, which was one of the wildest and most enjoyable performances I ever reviewed for the Village Voice. We looked, and naturally it’s on Vimeo. It’s a total classic, a postminimalist paradigm, up there with Piano Phase and Music in Fifths.

Neither Gone Nor Totally Forgotten

Tomorrow afternoon Bard’s student percussion group, coached by the SÅ Percussion quartet (UPDATE: thanks to Paul Epstein for the diacritical marking), is performing my Snake Dance No. 2, along with works by Daniel Bjarnason, Martin Bresnick, Steve Reich, and John Cage. It’s in Sosnoff Theater at the Fisher Center at 3. I wanted to post more in advance, but Arts Journal seems to have had a new bot attack the last few days.

On April 11, I think, pianist Nicolas Horvath is presenting one of his Glassworlds marathons at the Palais de Tokyo Museum in Paris: many hours of piano music by Glass and inspired by Glass, my Going to Bed included. He’s got more of these scheduled than I’m able to decently keep track of.

“Angels Join in Distance”

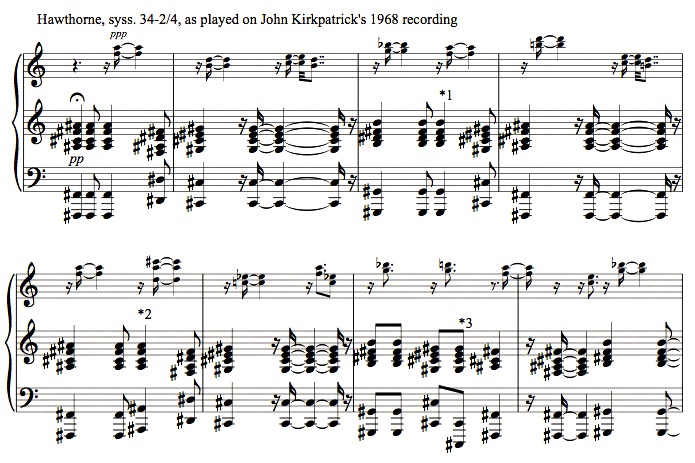

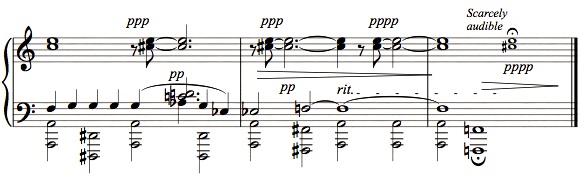

It finally occurs to me that it would be a public service to make known the quiet “harmonic” thirds (denoting “angels” joining in in the distance) that John Kirkpatrick adds to accompany the passage quoting the hymn “Martyn” in his 1968 recording of the Hawthorne movement of the Concord Sonata, about four or five minutes in. The idea from Hawthorne’s story “The Celestial Rail-Road” (a parody based on Pilgrim’s Progress)  is that the travelers on the train to the Heavenly City are hearing the hymn of the pilgrims who are going there on foot; it’s Ives’s musically-motivated idea that the angels join in. Below is the example from my book, which includes the extra notes Kirkpatrick plays, notated a little differently than in Kirkpatrick’s own personal version of the Concord, but following the rhythms that Ives himself wrote in the corresponding passage of the Fourth Symphony, second movement. The asterisks note chords in the 1920 edition that Ives would change for the 1947: all of them improvements. Pencil the top staff’s dyads into your own score and play them from now on! Let’s make this the new (optional) performance practice!

What Is the Concord Sonata?

I have been able to locate, on the internet, 33 35 38 [see update below] commercially available recordings of the Concord Sonata (well, actually only 32 37, since one of those is Jim Tenney’s recording, which one can hear on Other Minds, but which isn’t for sale). Of those 33 38, I possess 19 24, and two one more (the John Jensen and the Roberto Szidon, which latter I think I used to have on vinyl but can’t find) are on their way in the mail. I am going to disappoint readers of my book, and probably of this blog as well, by refusing to name my favorite. There are several reasons for this. One is that that’s a music critic’s job, and I’m no longer a critic; I’m interested in the sonata, as sketched and printed, not in its various instantiations. Another is that I just don’t plan to get familiar enough with all of them to be able to recognize in a blindfold test which is which. And the most important is that I’m not a good enough pianist to register a really well-informed comparison opinion in a book as scholarly as I mean this one to be. In matters of touch, tone color, inner voices, and so on, I’m just not that impressed with the authority of my own opinion. If it’s some consolation, I’m currently tremendously wowed by Marc-André Hamelin’s second recording of 2004. And John Kirkpatrick’s classic second recording of 1968 is so firmly embedded in my ears that I tend to compare all the others to it.

But I am interested in the statistics and performance tradition, and I think it’s worth knowing which pianists used which available variants. The most important feature is whether the optional flute is used at the end of Thoreau. I consider it not optional at all, really, but crucial. For one thing, there’s an early, pre-1914 manuscript of a passage for flute and piano using an early version of the “Human Faith” theme – when it had not yet acquired the E-E-E-C Beethoven’s Fifth motive – which I think strongly suggests that that theme was originally conceived for Thoreau (Henry David Thoreau loved to play the flute while boating on Walden Pond), and that it was, in fact, the generating idea of the entire sonata. Also, Ives equivocated on what the piano should play when the flute is absent, and in all versions left the melody at this point distressingly incomplete. Thus I have come to find the versions without flute distinctly unsatisfying.

More problematic is the questionable appearance of the brief viola solo called for at the end of Emerson. It seems to be a holdover from the Emerson Concerto from which the Emerson movement eventually evolved, and while I have seen some emphatic comments that the viola definitely wasn’t intended to be played by an extra soloist, I can make a reluctant case from the manuscripts that Ives did indeed call for it. In live performance I think it would be more distracting than it’s worth, but on recording it can have a certain charm. I certainly have no objection to omitting it.

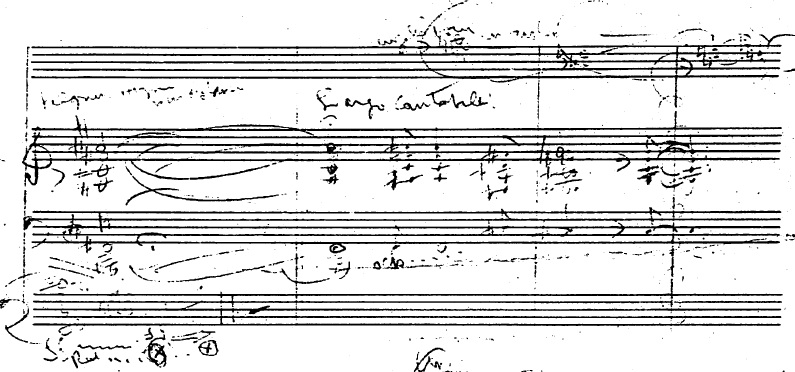

Even more controversial are the extra dissonant thirds played in high register during the quotation of the hymn “Martyn” when it appears in Hawthorne in the key of F#. Ives toyed with these thirds in an early sketch (f3956):

Next to and in explanation of these thirds you can scarcely make out at the top, in Ives’s scrawly handwriting, “angels join in distance,” which is a programmatic reference to Hawthorne’s short story “The Celestial Rail-Road” – it took me many trips to Yale’s Sterling Library to decipher what he wrote on the original sketch, and I later found it confirmed in a Kirkpatrick transcription. Ives later included some of these thirds in his piano piece based on Hawthorne The Celestial Railroad, and developed them even further in the analogous passage in the second movement of the Fourth Symphony. But he didn’t include them in the 1920 score, and, after a quarter-century’s deliberation (very sadly, in my opinion), opted not to use them in the 1947 score either. Yet Kirkpatrick, who didn’t include them in his 1945 recording, added them to his 1968 recording, whence many fans like myself became irrevocably accustomed to them, and found them perfectly evocative and, even more, entirely Ivesian. A certain performance tradition has grown up around them, and out of my 19 24 recordings, eight nine of the pianists include them.

And so, along with a few other less obvious variants, these are the three touchstones around which my choices among the recordings revolve. Of the recordings I own, the statistics come down as follows, listing what is included in each:

Pierre-Laurent Aimard: flute, viola, angels

Easley Blackwood: flute, no viola, no angels

Donna Coleman: flute, no viola, angels

Jeremy Denk: flute, no viola, no angels

Nina Deutsch: no flute, no viola, angels

Peter Geisselbrecht: no flute, no viola, no angels

Bojan Gorišek: flute, viola, no angels

Marc-André Hamelin 1988: no flute, no viola, no angels (but liner notes by myself)

Marc-André Hamelin 2004: flute, no viola, no angels

Herbert Henck: flute, viola, no angels

John Jensen: flute, viola, no angels

Gilbert Kalish: flute, viola, angels

John Kirkpatrick 1945: no flute, no viola, no angels

John Kirkpatrick 1968: no flute, no viola, angels

Aloys Kontarsky: flute, viola, no angels

Alexei Lubimov: flute, viola, angels

Steven Mayer: no flute, no viola, angels

Alan Mandel: flute, viola, no angels

Giorgio Marozzi: flute, viola, no angels

Yvar Mikhashoff: flute, no viola, angels

George Papastavrou: flute, no viola, no angels

Robert Shannon: no flute, no viola, no angels

James Tenney: flute, no viola, no angels

Nicholas Zumbro: flute, no viola, angels

(I’ll add the Jensen and Szidon when they arrive.) So 18 out of the 24 include the flute, and of those, nine also have the viola. Interestingly, the European pianists have been the most literal, insisting on the extra instruments and omitting the angels; perhaps they’ve had less trouble affording the extra performers. My own, admittedly subjective, ideal recording would contain the flute and angels but no viola, though I don’t object strongly to the viola. The only one three that matches my ideal in that sense is are the Donna Coleman, Nicholas Zumbro, and Yvar Mikhashoff. But another statistic to be taken into account is the timing of the movements, and especially Emerson, which varies widely in duration, ranging from 12 minutes to 19. At 50:19, Coleman’s is the second-slowest recording I own, next to Marozzi at 54:35, and there is a recording I don’t have just got, by Bojan Gorisek, that weighs in at a hefty 62:14, with a Thoreau of more than 21 minutes, eight minutes longer than any other recording – I’m almost afraid to hear it it’s kind of mesmerizingly hypnotic, with quarter-note = 15 during the A-C-G ostinato sections. Curiously, the shortest two recordings are both by Kirkpatrick, except for Kontarsky’s furiously rushed (at 35:58, though mostly very effective) reading. (As you would imagine, Kirkpatrick’s collector’s-item 1945 vinyl recording also uses more of the 1920 score than any of the others.) Denk’s recent and widely celebrated recording is a very literal reading of the 1947 score, as though he’d never listened to another recording, and I particularly love the way he recorded the flute, almost in the background as if it is emerging from the listener’s subconscious. The recordings I don’t have are by Werner Bärtschi, Louise Bessette, Jay Gottlieb, Ciro Longobardi, Philip Mead, Roberto Ramadori, Manfred Reinelt, Per Salo, Richard Trythall, and Daan Vanderwalle. I may buy a few more if I can, but plan to go to no extreme lengths to obtain them. A review here made me curious to hear the Longobardi, but Italian Amazon will not deliver it to my address.

Based on Ives’s oft-made comments about Emerson never having felt completed, some scholars, such as Stephen Drury (in his introduction to the Dover score) and Sondra Rae Clark (in her 1972 dissertation “The Evolving Concord”), have expressed a belief that the Concord is open-ended, and that no version is definitive. I agree to a point, with the exception that I think Ives also made it clear that he preferred the 1947 score to the 1920 in every way, and that the variants in the earlier edition are never equal, let alone better. I do think that the pianist who takes on the Concord needs to look through the manuscripts and especially the 17 scores from the 1920 edition into which Ives penciled variants and further ideas. I’m all for variations in performances of the Concord, and to each pianist his or her own personal edition. But I also often find clear musical reasons why one version is stronger than another. The authentic versions of the Concord are varied, definitely, and delightfully so, but – in terms of notes played – not infinite.

UPDATE: Oh, and if you do know of a recording I haven’t mentioned here, I would be grateful if you’d bring it to my attention.

UPDATE: Just found mention of old recordings by Rene Eckhardt, Ronald Lumsden, and Tom Plaunt.

That Familiar Stabbing Pain

It doesn’t matter how long you’ve been out of the newspaper business, you never become immune to headline envy. Arnold Whittall’s review, in The Musical Times, of the Ashgate Research Companion to Minimalist and Postminimalist Music is titled: “It’s Gonna Reign.”

Composition Teacher Bait and Switch

Funny how Robert Palmer’s name comes up three times in a week, and then Howard Hanson’s twice. That Americana school sucks me back into their vortex occasionally.

Two weeks from tonight I’m giving a talk on William Duckworth at Bucknell University, where he spent his teaching career. So for the first time I’m listening to the six hours of interviews I did with him while he was dying, which I had avoided doing for fear I would get too emotional. In going straight from East Carolina University to the University of Illinois in the mid-’60s, Bill went from the heart of neoromantic Americana to post-Cage conceptualism, and skipped over the 12-tone movement entirely. He related a story his teacher Martin Mailman had told him about studying with Hanson.

Apparently when a student would bring Hanson a 12-tone score, Hanson would place it on the piano and look over it carefully, play a chord on the piano, and ask, “Is this the chord you want right here?” The student would say, “Yes it is.” “Are you sure you want this chord?” “Yes.” “Well, then why didn’t you write that chord, because this is the one you wrote!”, and he’d play a different one. The point being that he didn’t think 12-tone composers could hear the music they were writing.

A Sunken Bell Well Immersed

Drew Massey’s John Kirkpatrick book has far more information than I’d ever seen before on Carl Ruggles’s opera The Sunken Bell, including score excerpts. Ruggles worked on it from 1912 on and off until 1927, never completed it, but was such a convincingly blustery self-promoter that he actually got the Met interested, even though he had yet to complete a major piece of music. He finally destroyed the score in 1940, though Kirkpatrick “spirited away the sketches that were housed in the shed of Ruggles’s home in Arlington, fearing that Ruggles would throw those out as well.” (p. 104) For once in the history of music, I am thankful to a composer for having destroyed one of his scores. The Sunken Bell  looks awful. It’s got a German-Romantic fairy-opera plot in turgidly archaic English with lines like, “Hey, dost thou not hear?”, surrounded by half-diminished seventh chords and nervous one-note-rhythm mottos. It looks like the most ill-conceived opera, and the most absurd composer-subject combination, outside of Theodor Adorno’s projected and also mercifully incomplete 12-tone opera on Tom Sawyer, Der Schatz des Indianer-Joe. Would have been better had they traded librettos – at least it couldn’t have been worse.

And there’s a question. Ruggles was a well-known crotchety old anti-Semite and serial liar, but we all shrug and smile over him because we love Sun-Treader. Meanwhile his friend Ives liked to revise his music and had a poor memory for dates, and people act like he’s a major fraud. Why the double standard?

Puppeteer of American Composers

Just in time, Peter Burkholder recommended to me (announced to the entire Ives Society, actually) Drew Massey’s new book John Kirkpatrick, American Music, and the Printed Page. It’s a detailed, sometimes very technical look at Kirkpatrick’s aggressive influence as editor on the composers he adopted, including most famously Ives and Ruggles, but also Roy Harris, Ross Lee Finney, Hunter Johnson, and – ! – my old friend Robert Palmer. I can hardly say how much I admire Massey’s willingness to tackle a subject that seems to have so little profile and sex appeal on the surface, but does so much to elucidate what’s gone on behind the scenes in American music. The most telling sentence comes near the beginning: “Although many praised his commitment to American music, in the course of my research I have also heard Kirkpatrick called ‘quite a piece of work,’ a man ‘swallowed by the leviathan of [his] own conceit,’ and someone who deserved ‘a punch in the mouth.'” Most helpful for me, Massey teases out the painful process by which Kirkpatrick gradually weaseled out of helping Ives prepare a second edition of the Concord Sonata – and then spent the rest of his life making his own private editions of it with bar lines and meters and many of the sevenths and ninths “normalized” into octaves. A mesmerizing final chapter relates how the evolving editorial policies of the Charles Ives Society formed and reformed in relation and reaction to Elliott Carter’s and Maynard Solomon’s charges against Ives – and while Massey was mentored by Burkholder, who served many years as the Society’s president, and thus has an inside scoop, he does not merely act as Burkholder’s mouthpiece. One might even hope that having this historical account out in the open might cathartically bring that whole sorry issue to a close. I’ve already added a thousand words to my Concord book based on what Massey’s taught me.

Just in time, Peter Burkholder recommended to me (announced to the entire Ives Society, actually) Drew Massey’s new book John Kirkpatrick, American Music, and the Printed Page. It’s a detailed, sometimes very technical look at Kirkpatrick’s aggressive influence as editor on the composers he adopted, including most famously Ives and Ruggles, but also Roy Harris, Ross Lee Finney, Hunter Johnson, and – ! – my old friend Robert Palmer. I can hardly say how much I admire Massey’s willingness to tackle a subject that seems to have so little profile and sex appeal on the surface, but does so much to elucidate what’s gone on behind the scenes in American music. The most telling sentence comes near the beginning: “Although many praised his commitment to American music, in the course of my research I have also heard Kirkpatrick called ‘quite a piece of work,’ a man ‘swallowed by the leviathan of [his] own conceit,’ and someone who deserved ‘a punch in the mouth.'” Most helpful for me, Massey teases out the painful process by which Kirkpatrick gradually weaseled out of helping Ives prepare a second edition of the Concord Sonata – and then spent the rest of his life making his own private editions of it with bar lines and meters and many of the sevenths and ninths “normalized” into octaves. A mesmerizing final chapter relates how the evolving editorial policies of the Charles Ives Society formed and reformed in relation and reaction to Elliott Carter’s and Maynard Solomon’s charges against Ives – and while Massey was mentored by Burkholder, who served many years as the Society’s president, and thus has an inside scoop, he does not merely act as Burkholder’s mouthpiece. One might even hope that having this historical account out in the open might cathartically bring that whole sorry issue to a close. I’ve already added a thousand words to my Concord book based on what Massey’s taught me.

And, Americanist aficionado that I am, I gain a lot from Massey’s accounts of composers who seemed up-and-coming in the 1940s but have left little trace now. Kirkpatrick and Palmer bonded partly over their bisexuality (some of Kirkpatrick’s ideas about music were conditioned by mid-century theories linking homosexuality and immaturity), and Palmer had a rough time at Eastman because the composer-director Howard Hanson went on a crusade to cleanse the faculty there of suspected homosexuals. Well, you probably weren’t going to listen to much more of Hanson’s music anyway. And there’s enough attention paid to Palmer’s music for me to firm up my sense of why I have such a soft spot for it, like this excerpt from his Second Piano Prelude in the charming meter of 17/16:

This looks like an early piece of mine that I forgot to write. Notice the G-Ab clash in the first (actually third) measure. We need a lot more books like this, books that don’t content themselves with the public record but go backstage and unravel what ropes were being pulled by whom to make the stage machinery work. I hope Massey will expand on his research and continue shining spotlights into the dim back rooms of American music. (I shouldn’t say that, I never continue with anything. After my Cage book I was done with Cage, and after my Ives book I’ll be done with Ives. Books are how I get the music I’m wowed by out of my system.)

Ives as Reviser

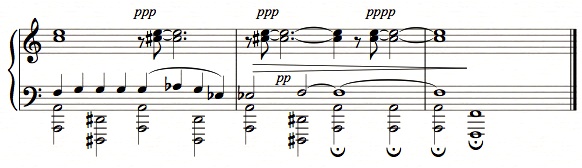

Here are the last three measures of the Concord Sonata‘s Emerson movement, as published in the score he sent out in 1921, which is now in public domain, and which – ill advisedly, in my view – has just been reprinted by Dover:

And here are those last three measures in the second edition of 1947:

There are several changes here – the addition of the C-D cluster, the reiteration of the final treble dyad, the replacement of fermatas with what seems a more judicious ritard – but the one that interests me most is the replacement of the final D# with F# in the bass line. By setting up an F#-A dyad in the listener’s ear, it renders the final F (which, of course, is the close of an intentional Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony motive) a touch more surprising. The A, D#, and F could be heard as belonging to the same harmony, but the A, F#, and F cannot – in addition to which, in conjunction with the tenor melody, the final D# came precariously close to rooting the tonality in Eb (D#), lessening the delicious ambiguity, and making the final F sound like a second scale degree rather than a new, unexpected tonic. It’s a small change, but a poetic one and perfectly right. In addition, the F-E-C# at the end (with the added harmonics) expresses a 1-3 pitch motive (minor second-minor third) that is important earlier in the movement, being first heard starting from the left hand’s second note. This pitch set is now found in the closing bass pitches F#-A-F as well.

If it matters to anyone, the change from D# to F# is not included in the Four Transcriptions from Emerson, which, based on Emerson, was completed and copied in 1926, which suggests that Ives must have made the change after that date.

Aside from the better-known big dissonant parts added to Emerson, there are dozens of such improvements that Ives made to the 1920 score in the 1947, things that hadn’t been quite right yet, that were surprising and original but not yet magical. I’m detailing many of them in my book. Thus I think it’s rather a shame that Dover has issued a cheap reprint of the 1920 score, which is deficient in many, many respects. Its reappearance in the popular Dover series will convince many buyers that they are getting the real Concord Sonata – and though not everyone agrees with me, I believe it does this great work a disservice.

(Of course, I am sufficiently inured to the internet to know that since I expressed a preference, I’ll now get plenty of comments saying they like the 1920 version better, just as when I produced a clean recording of a Harold Budd piece, there was no end of people saying they preferred the one with the baby crying in the background. If I blogged that I preferred my wife’s cooking to roadkill, the defenders of roadkill would form a line. Such comments will be taken seriously if the writer can explain his reasoning in as much logical detail as I have above.)

Gann Plays Gorecki

I ain’t kiddin’. My son Bernard is reviewed in the Times today for playing guitar in a re-orchestrated version of Gorecki’s Third Symphony. At the bottom of the article (to save you reading it), Steve Smith says that the soloist “Megan Stetson… sang with luminosity and poise, the trenchant ache of her lines no less tear-inducing for being backed by Bernard Gann’s fuzzy black-metal guitar tremors and Greg Fox’s double-pedaled kick-drum thunder.” Greg, a Bard grad, plays with Bernard in Guardian Alien and used to play with him in Liturgy.

Poisoned Musicology

I’m on spring break, and finishing up the obligatory chapter for my Concord Sonata book in which I compare the 1920 and 1947 editions. The research is drawing me into an argument that I had hoped to avoid altogether (and I hate to even call it an argument, because only one side makes sense): namely, whether Ives later added dissonances to his music in order to make it look as though he had written highly dissonant music earlier than the other famous modernist composers, as charged by Elliott Carter and later Maynard Solomon. To me, this is a totally bogus charge and I consider it time to move past it. I still intend to make this the first Ives book in 25 years in which the name Maynard Solomon does not appear. What’s muddied the waters, and made it impossible for me to abstain, is that pianist John Kirkpatrick made a parallel statement in justification of his refusing to help Ives prepare the 1947 edition, and of his preference for the 1920 version. Since I’m eager to let this dumb argument die down, I actually feel like airing more of my thoughts on the matter here, and fewer of them in the book.

What Kirkpatrick said is milder than Carter’s charge. He thought that Ives added dissonances not in order to claim priority, but to thumb his nose, to keep “pride of place” with other composers of the 1920s who were writing dissonant music. His specific complaint is that Ives went through the Concord adding accidentals to turn octaves into “denatured octaves” (major 7ths, minor 9ths), ruining the work’s lyricism. But I’ve gone through both Concords with a fine-tooth comb, and I can’t find more than a dozen instances where he did this. I literally can’t see what Kirkpatrick was talking about, and I suspect he was reacting to Ives’s occasionally truculent personality, and possibly even taking Carter’s charge for more than it was worth, rather than looking at the notes.

You will tell me, if you’re in the know, that Geoffrey Block’s article “Remembrance of Dissonances Past,” in Lambert’s Ives Studies, disposes of this matter with regard to the Concord, and to a certain extent it does. Block compares the sketches for the Emerson Concerto (which are such a jumble I quickly get tired just trying to pore over them) with the Four Transcriptions from Emerson, which we know were completed and well-copied by 1926. Some of the added dissonance (or, one should say, texture) came from the concerto, which no one doubts was sketched out between 1907 and 1913, as Gayle Sherwood Magee’s studies of the ms. paper have convinced everyone. Therefore, we can prove that Ives’s most radical changes in Emerson were made by 1926, and that many of them (not quite all, apparently, and who cares?) stemmed from music he had written more than a decade earlier. But Ives made changes on every page of the sonata, and Block hardly mentions Alcotts and Thoreau, and doesn’t deal with Hawthorne in any detail.

And if you go through the entire sonata without an axe to grind, it’s very apparent that Ives’s number-one concern, in all movements, was to thicken the texture, make the sonata more dramatic and virtuosic, and to make more powerful passages whose counterpoint was a little too thin to be effective. There are a handful of “denatured octaves” and quite a few added 7ths and 9ths, but vastly more octaves added to lines in the bass and treble, and also internal 5ths added to octaves in the bass and 3rds added to octaves in the treble. The pianistic virtuosity is  noticeably upgraded, but the dissonance level could hardly be raised from what it already was in many places. The point, to me, is that the 1920 version, for whatever reason, was left a little timid and at times non-pianistic. It was Ives’s first mature and experimental work to be published, it was a quixotic venture in self-publishing, and it came out with a lot of flaws, which Ives very reasonably worked to correct in his second edition. More power to him.

The main points as I see them are these:

1. Every composer who ever lived has possessed the legal, moral, and de facto right to revise his or her own music, for whatever reason, Ives included. Ives himself said that every time he looked at the Concord, he wanted to change something. I’m like Ives insofar as I rarely prepare an old score for a new performance without tinkering with it. I just added several measures to a piece I wrote in 1987; am I therefore mendacious? If, in that revision, I chanced to do something no one had done before, will the history books take me to task for not having done it earlier? Can I have revised my music without an ulterior motive beyond making it better?

2. Carter’s insistence that Ives had some self-serving ulterior motive for the kinds of changes he made was ungenerous, arbitrary, and without evidence. (Carter had a definite bug up his ass about Ives. A close friend of mine who met with Carter only a few years ago tells me he went into an unprovoked tirade about how lousy Ives’s songs were.) If one could find a single place in Ives’s writings or recorded utterances in which he had claimed to be the first to do anything, then one might have to partly concede Carter’s point. But all Ives ever said was that he had not been influenced by Schoenberg, Stravinsky, or Hindemith. Critics had confidently accused him of such influence, and since Ives hadn’t heard the music they referred to, he, very naturally, indignantly denied the possibility.

3. If Carter, as he said, was miffed because Ives was being accorded priority, then his anger was rightly directed at those who were doing the according, and not at Ives. As it has happened, musicologists have done a pretty damn good job of figuring out who did what when, and I don’t see any early 20th-century composer getting any credit he didn’t deserve.

4. Those many scholars who have looked at the issue have found that, while Ives’s dating was erratic, every piece was written within five years, and more often two years, of when he said it was, sometimes after and occasionally before. This level of imprecision is hardly unusual. I’ve gone through John Cage’s writings and works, and his dates are notoriously unreliable. For instance, when was the prepared piano invented, 1938 or 1940? The evidence suggests the latter date, but there is a hand-written score of Bacchanale, the first prepared-piano piece, with the date 1938 inscribed neatly at the top. Well, then, let’s charge Cage with mendacity! Cage says he studied with Suzuki in “the late ’40s,” but Suzuki’s first return to the U.S. since 1911 was in 1951, when he started teaching at Columbia. Well, what a liar that John Cage was! But the Cage people just shrug and correct the record, knowing that writing music is a composer’s job and writing history a musicologist’s. Cage often admitted he was terrible with dates. Personally, I’ve always scrupulously dated my scores upon completing them, and since they’re all laid out on the worklist at my web site, I see the dates often and rarely make such errors, but ask me about some event in my life not related to an official calendar, and I’m as likely as anyone to misplace it by a few years. Unlike Ives’s, my pieces usually got played soon after I wrote them, and my manuscripts have not spent decades getting stacked in a barn.

5. Amadeo Roldan wrote the first pieces for percussion ensemble. That bought him a footnote in a few history books. Any worthwhile composer cares far more about the quality of his music than about whether he was the first to try some technical device. That Carter could concoct such a charge, I’ve always thought, says infinitely more about him than it does about Ives. That Solomon fell for it tells me everything I need to know about his grasp of composer psychology. That two such men working in tandem and alone could besmirch the reputation of a composer widely known for his generosity, self-effacement, humility, and spirituality is a tragedy of music history.

6. What does it matter? Was an Ives piece fabulous if he finished it in 1915, but only so-so if he really worked on it until 1919? What happened in the world in those four years that would have made the Concord easier to write? We possess a datable Ives note from 1913 mentioning having played the Concord for a friend the year before. Can anything in the manuscripts contradict that? There are piano pieces that Leo Ornstein performed in the 19-teens, confirmed by printed programs, that he didn’t write down until the 1930s. Occasionally a student will play me a piece of his, and I’ll ask to see the score, only to be told, “Oh, I haven’t written it down yet.” According to Lou Harrison, Ives had virtual total recall for every note in his music. He was certainly capable, as many people have been,  of composing a piece without writing it down. Not all of history shows up on manuscript paper fifty years later.

It’s easy to see why I don’t want to put all of this in the book. That I have had the chance to spend years studying the manuscripts of the Ives piano sonatas has been one of the great joys of my life, and it’s a crying shame that the world of Ives scholarship has been poisoned by these imputations of motivation for which there could never be definitive proof on either side – since, lacking a textual confession, the private motivations of a man dead for six decades can never be absolutely known. The original charge remains far better circulated than the myriad scholarly refutations of it now buried in JSTOR, and so we all continue to tiptoe around it. I had intended, in my book, to treat the matter as settled, but I find that I cannot do so and engage adequately with the current literature.

Here is the conclusion of what I say in the book about the Concord‘s two editions:

“It is worth restating, I think, that the sum of all of these changes does not at all add up to a picture of an ambitious modernist trying to ‘jack up’ dissonance in order to keep current in the avant-garde, but something else entirely different: an amateur, so to speak, someone who had spent decades alone with his scores and was not used to scrutiny by objective eyes, trying to professionalize the appearance of his score and make it more pianistic, more dramatic, more effective and defensible. It may well have been that in 1921 when he sent those scores out, Ives expected to receive little attention, and let himself be satisfied with notational and textural solutions that didn’t bother him when he was playing the piece alone in his study. The 1920 score is something of a homemade job, and looks like it in places (for instance, I direct your attention to the sketchy-looking top staves of page 33). But in the 1920s and especially after 1939, with the ears of the world suddenly turned toward him in amazement, the Concord score had to be held to a new standard. There may be Ives lovers uncomfortable with the idea that such a genius could produce, in 1920, a score brilliant but still so riddled with imperfections as the 1920 Concord seems to me now. But I far prefer it to Kirkpatrick’s picture of an arrogant careerist who, having produced a wonderful sonata, let himself get carried away and introduced flaws into it in order to show off his modernisms. And I think the reception history of the two scores, with every pianist’s perennial reliance on the 1947 edition, abundantly proves that Ives, by and large, made exactly the right move. The Concord, had it been limited to its 1920 incarnation, would not be what it is today.”

Now, having that off my chest, perhaps I can finish my chapter.

A Long-Lost Name Resurfaces

I guess I’ve long been the biggest Roy Harris fan left. In my youth I would occasionally run across a vinyl record of music by one of Roy Harris’s students, who wrote in a similar style, named Robert Palmer; I remember his cantata Abraham Lincoln Walks at Midnight, but no longer have a recording. Recently, in my research into Ives, Blitzstein, and other composers, I’m starting to run into Palmer’s name again, partly because John Kirkpatrick championed his piano music and would occasionally mention him to Ives. So I went to see what remains of his music out in the world; I already had his Third Piano Sonata and some choral music, and I found a delicious Clarinet Quintet and Piano Quartet, as well as a Second Piano Sonata with a Harrisian first movement in 5/8. Palmer’s piano music tends to be rather jumpy in the asymmetric, repeated-note way so characteristic of mid-century Americana, but his chamber music drapes long lines over nostalgic harmonies bittersweetly tinged with bitonality – qualities I adore and aim for in my own music, though I’m coming from minimalism and he came from neoclassic sonata form.

I guess I’ve long been the biggest Roy Harris fan left. In my youth I would occasionally run across a vinyl record of music by one of Roy Harris’s students, who wrote in a similar style, named Robert Palmer; I remember his cantata Abraham Lincoln Walks at Midnight, but no longer have a recording. Recently, in my research into Ives, Blitzstein, and other composers, I’m starting to run into Palmer’s name again, partly because John Kirkpatrick championed his piano music and would occasionally mention him to Ives. So I went to see what remains of his music out in the world; I already had his Third Piano Sonata and some choral music, and I found a delicious Clarinet Quintet and Piano Quartet, as well as a Second Piano Sonata with a Harrisian first movement in 5/8. Palmer’s piano music tends to be rather jumpy in the asymmetric, repeated-note way so characteristic of mid-century Americana, but his chamber music drapes long lines over nostalgic harmonies bittersweetly tinged with bitonality – qualities I adore and aim for in my own music, though I’m coming from minimalism and he came from neoclassic sonata form.

I am astonished to learn that Palmer died only in 2010 – Grove doesn’t even list his end date yet – and next year will be his centenary. He lived to be 95. I wish now I had run across his name again a decade ago, for he would have been a wonderful person to interview, not only because he seemed near the center of American musical life during the WWII era but because I am hungry for more of his own music. Grove lists his most important teacher, more than Copland or Harris, as Quincy Porter, another figure whose chamber music I carry a brief for. Palmer got a teaching job in Kansas in the 1940s and soon after went to Cornell. One supposes he faded from the composition world, as “conservatives” did, due to the uprising of serialism in the ’60s, but he lived long enough to see the Americana school to which he belonged partly restored to favor, yet without seeming to have re-emerged with it. (And, insult to injury, the ubiquity of an eponymous pop star makes his music difficult to look for.) You know how saddened I am to see wonderful music go missing, and to see the producers of it go unappreciated. Presumably there are Palmer students and friends out there, and it would be nice to see his music reappear and get its due.

Happy Day, Ben

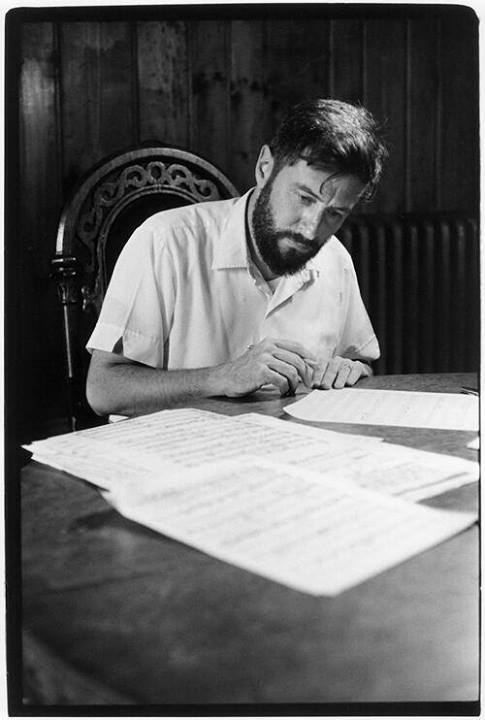

Via Facebook, microtonal composer-guitarist David Beardsley posts this wonderful photograph by William Gedney, circa 1966, of composer (and, much later, my teacher) Ben Johnston for his 88th birthday today:

Still near the beginning of his microtonal period, around the time of his Quintet for Groups, Sonata for Microtonal Piano, and Third Quartet, he’s probably juggling 80 different pitches in his head.