Today is not only the 197th birthday of Henry David Thoreau, but the milestone 60th birthday of the composer (and my good friend) Robert Carl. His Fourth Symphony is on my web site if you’d like to celebrate. (Be warned, the beginning is very soft.)

Reunion Anxiety

I’ve been sitting on the scoop that the black metal band Liturgy is indeed reuniting for a new tour and record, but Pitchfork broke the news. That’s Bernard Gann in the back, I think, though with enough hair he and Greg Fox can look almost indistinguishable. Bernard’s other band (or rather, one of his other bands) Guardian Alien was interviewed by High Times magazine back in May, but for some reason it was only in the paper magazine, and never appeared on the internet.

Composer Casualties

I’m kind of fascinated by the First World War, which I think of as a catastrophe unparalleled for its combination of massive scale and utter pointlessness. I particularly recommend Adam Hochschild’s book To End All Wars, one of the most fascinating history books I’ve ever read; and Stanley Kubrick’s Paths of Glory is a film I can always watch again, as is Paul Gross’s Passchendaele. I’m commemorating the centennial of the war’s inception by listening to music of George Butterworth (1885-1916), who, as far as I know, was the most well-known composer who died fighting in it, leading his men in the Battle of the Somme. Although tomorrow I’ll probably also listen to the lovely Fourth Symphony of Albéric Magnard (1865-1914), who died when his house was burned by German soldiers. I have kind of a thing about works written during that war as well, such as the Concord Sonata, Socrate, and The Planets.

Pre-Redivision Period Music

Here’s an interview with Daniel Lentz, one of my favorite composers. I love that the critic quotes John Schaefer as saying, “His works look back to an earlier time when music was not so divided between serious and popular. This is music that will appeal to a broad range of listeners.†Yeah, that was back during my lifetime. Good to have it validated that that period’s officially over, I guess.

Here’s an interview with Daniel Lentz, one of my favorite composers. I love that the critic quotes John Schaefer as saying, “His works look back to an earlier time when music was not so divided between serious and popular. This is music that will appeal to a broad range of listeners.†Yeah, that was back during my lifetime. Good to have it validated that that period’s officially over, I guess.

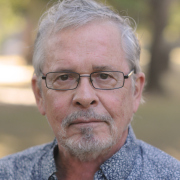

A Pseudo-Milestone, but Feels Real

I have just completed a first draft of Essays After a Sonata: Charles Ives’s Concord. It is currently something over 136,000 words, which is just about the length of my American Music book; plus, there are hundreds of musical examples. There are fourteen chapters, as follows:

The Story of the Concord Sonata, 1911-1947

The Programmatic Argument (and Henry Sturt)

The Human Faith Theme and the Whole-Tone Hypothesis

Emerson: The Essay

Emerson: The Music

The Emerson Concerto and its Offshoots

Hawthorne and The Celestial Railroad

Hawthorne: The Music

The Alcotts

Thoreau: The Essay

Thoreau: The Music

The Epilogue: Substance and Manner

The First Piano Sonata

Editions (1920 versus 1947) and Performance Questions

The book is due to Yale University Press in September. I wrote it in three years, and was turned down for four five major grants, any of which would have allowed me to take a semester off teaching to work on it. Now, after a little rest, I need to reread twenty or thirty books to make sure I didn’t miss anything; locate sources for and complete all the footnotes that I didn’t take time away to pin down while I was writing; and read the entire thing out loud to myself six times, removing infelicities as I go until every sentence rings like a crystal goblet, so that the reader’s inner ear is drawn irresistibly through the prose. This last step is deemed optional in the scholarly world, but the fact that I do it makes publishers love me. And yes, the book is backed up on multiple external hard drives.

Then I send in the book to Yale, and savor a tremendous but specious feeling of closure. Four months go by, and I get back the edited manuscript, on which I spend three weeks (while teaching) trying to fix a million little things. I send it in again. Two months go by, and I get the galleys, with a couple hundred little mistakes to rectify. Then they say it will be out in April, which will mean October for some reason. It’s my sixth time through this routine.

I am very, very good with deadlines. That’s why I’m so lax with my students’ papers. When I was in college I hardly ever turned in a paper on time. In nineteen years at the Village Voice, I only missed a deadline once, and that by a couple of hours. Real deadlines, on which one’s life and income and career depend, are very different from the paper deadlines of academia. I don’t buy (and maybe I shouldn’t base it on my own deplorable psychology) the argument that students need to be trained to be on time or they’ll never be punctual once they graduate. I once cheerfully graded a paper, the week before the student graduated, for a Beethoven course he had taken as a freshman. I’m just as good with musical deadlines, too. The very offer of a paid commission makes music sing in my ear. Once when the conductor of the Indianapolis Symphonic Chorus offered me a $10,000 commission, I heard the opening of the piece (Transcendental Sonnets) in my head before he could finish the sentence. Though I must admit, my promptness derives less from courtesy or professionalism than from an abject fear of screwing up.

UPDATE: There’s an astrological principle underlying the psychology of this post. I have Sagittarius rising, and Sagittarius is perceived as flaky and unstable. But most of those with Sagittarius rising have the extremely stable sign Taurus on the sixth house of work, and in work situations we are much more reliable than people imagine we will be. It’s also, I’m sure, why people think that because my Sagittarius writing style is “breezy, casual, and journalistic,” my Scorpionic scholarship and analysis can’t be solid and thorough, which in fact they are. After 58 years of it, I get awfully tired of being perceived as less heavyweight than I am. Perhaps some of my Sagittarius-rising readers will sympathize.

The Charm of Impossibilities

I am sitting here trying to write microtonal polytempo music on Sibelius. I have found the most aggravating, patience-requiring method of composing in the history of music. I have spent the last two hours trying to fill three measures of music – largely because Sibelius will not allow a pitch bend command to be pasted onto a note in a tuplet. If Schoenberg really was trying to make it impossible for his students to compose, as Cage claimed he said, he would have made them do it this way. Future generations of composers will look at my music and say, “I’m sure glad he did it, because I certainly wouldn’t have tried.”

Friends of Bob

After Bob Ashley’s death, Ed McKeon put together a group of video tributes to him by his friends, and he’s now put them up on the web. This first video has personal statements from Pauline Oliveros, “Blue” Gene Tyranny, Roscoe Mitchell, Alvin Lucier, David Behrman, and Peter Gordon. The second one features Fast Forward, me, Jacqueline Humbert, Tom Buckner, Joan LaBarbara, Chris Mann, Alex Waterman, Sam Ashley.

Just in case you’re only interested in me (Mom), my part begins at 3:28 in the second video, and you can see what my living room looks like. But they’re all quite moving.

When Good Things Happen…

…to curmudgeonly people: I am not very sanguine about the advantages of the composing life these days, but let it be noted that one can be sitting on one’s screened-in porch savoring a Romeo y Julieta [that’s a cigar, kids] while talented young people are giving one of your works a gratifying world premiere on the opposite side of the planet. The Australian National University New Music Group, with soprano Jelena Mamic, did a lovely job on my The Stream (Admonitions), as you can hear in the linked video. And since I had forgotten writing it, it’s like I expended no effort at all, but get to enjoy the music and take the credit anyway. There must be an apropos Thoreau quotation, something about the flowers blooming without one having to harangue them….

One of the Greats: Elodie Lauten, 1950-2014

I awoke this morning to the rude shock of learning that my close friend Elodie Lauten has died, a fabulous composer whose music I’ve been championing ever since I was at the Chicago Reader in the early 1980s. Earlier this year I wrote her to congratulate her on winning the Robert Rauschenberg Award, and it took her quite a few days to respond. She said she had been in the hospital, lost a kidney to cancer, and was having trouble walking. We shared a couple more e-mails, and she sounded upbeat about the then-upcoming performance of Waking in New York, her lovely oratorio of Allen Ginsberg poems. Her last Facebook entry, praising the previous day’s performance with no hint of any trouble, was June 2. Apparently she didn’t recover, however, and died yesterday in Manhattan’s Beth Israel Hospital. At 63. (Born 1950, she shared a birthday with Ives, Oct. 20.)

I awoke this morning to the rude shock of learning that my close friend Elodie Lauten has died, a fabulous composer whose music I’ve been championing ever since I was at the Chicago Reader in the early 1980s. Earlier this year I wrote her to congratulate her on winning the Robert Rauschenberg Award, and it took her quite a few days to respond. She said she had been in the hospital, lost a kidney to cancer, and was having trouble walking. We shared a couple more e-mails, and she sounded upbeat about the then-upcoming performance of Waking in New York, her lovely oratorio of Allen Ginsberg poems. Her last Facebook entry, praising the previous day’s performance with no hint of any trouble, was June 2. Apparently she didn’t recover, however, and died yesterday in Manhattan’s Beth Israel Hospital. At 63. (Born 1950, she shared a birthday with Ives, Oct. 20.)

I wrote about her music recently in connection with the award, and won’t repeat that here. I will add that she was more of a martyr to her music than anyone I’ve known. Over the past couple of decades she moved to cheaper and cheaper apartments, and worked temp jobs to make ends meet. She got an occasional gig teaching electronic music or composition lessons thanks to Dinu Ghezzo, who was a guardian angel to her. Despite her near-penury, she was constantly working on getting her big operas, song cycles, and music theater pieces produced. She was as broke as any musician I’ve known, and yet she had more big projects on the front burner than most composers in far more cushy circumstances. I can’t help but think that, on some level, she worked herself to death. It’s an incomprehensible shame, because she had once had a big piece at Lincoln Center, and she always got good reviews – she was my number one example of a composer whose music delighted critics but never seemed to catch on with anyone else. Certainly her tuneful brand of postminimalism has not been in fashion lately, which affects many composers of my generation. She deserved a much bigger career. But I’m hardly the only one who thought so, and she had a crowd of supportive musicians determined to help get her music out. Her keyboard works are charming. Her vocal works deserve a big box set on Nonesuch, if not Deutsche Grammophon. She never wrote a bad piece. She was an oddly quirky, ever-upbeat personality with a touch of Zen mysticism. I kept thinking she would finally get her due someday. She just had to.

UPDATE:This reminiscence of her at Unseen Worlds rings very true.

Surprise Gift from the Younger Me

In case you happen to be in Canberra this Saturday (conflicts with my acupuncture appointment in Kingston, sadly), the ANU New Music Ensemble and their guests, Uncut Percussion, will give the world premiere of my The Stream (Admonitions), which I wrote in 1987 and forgot about until I ran across the manuscript this spring. (Here’s the Facebook page for the event, which reveals that they’re also playing a piece by my old friend Gerhard Stäbler.) I spent the year 1987 still living in Chicago but flying to New York City three times a month to review concerts and write for the Village Voice, so it’s not too surprising to me that a piece written amidst that chaos could have fallen through the cracks. It’s funny, of course I look at the score and know what the piece sounds like, but in another way I can’t really remember what it’s intended to sound like; editing it at this point blurs the line between composing and musicology. Though I shouldn’t downplay the originality of my own works, it’s somewhat in the style of Cage’s austerely simple pieces from the mid-1940s, like Experiences 1 & 2 and Dream, which I’ve always loved. The years 1986-1989 were the low point in my compositional life, and my music took a more Gannian turn again afterward. Nevertheless, the group’s director Alexander Hunter says rehearsals sound beautiful, they’re planning to tour the piece, and hopefully a recording will ensue to which you will have access.

UPDATE: It reminds me – when I was young I used to notice the awful, pretentious clichés on composers’ bios, and the worst, I thought, was “Wolfgang Trust-Fund’s music has been played on five continents.” Like that meant anything. But I performed Custer in Australia in 2003, had a piece played in Tokyo awhile back – if Japan counts as the Asian continent – and some friends played a piece of mine in Brazil 25 years ago, so I might as well dig it out: “Kyle Gann’s music has been played on five continents!” Just Africa and Antarctica to go, and then I’m done.

Anachronisms Happen

Via Susan Scheid, I learned that the Ghost Ensemble’s performance of my piece Sang Plato’s Ghost and other works actually got a review, by George Grella. I didn’t think that kind of thing happened anymore.

Messages from the Beyond

NEW HAVEN – [UDPATE BELOW] I’m spending three days at Yale’s Sterling Library poring over Ives’s manuscripts, for hopefully the last time I’ll need to do so before the book is done. I think today one manuscript page, f3680, taught me more about how Ives composed than I’ve ever known before. I can’t do the page justice by trying to reproduce it here, but it will be in my book, believe me. It’s the beginning of a 1st Piano Sonata, with an inscription “Pine Mt., Aug 1901.” Pine Mountain was a hill in Connecticut within walking distance of Danbury where Ives and his friend Dave Twichell (later his brother-in-law) built a shack to hang out in. Whether he wrote the date on the page at the time or later and got it wrong, who knows and who cares. The page is the beginning of a mildly polytonal sonata movement in a gently rocking 6/8 meter. Had it been written in the 1940s, you would call it mainstream conservative. But if you look at it with Ives’s First Sonata freshly in your head, you notice that the first measure is similar to that of the First Sonata’s third movement, mm. 3-4 from the middle of the first movement, mm. 12-17 similar to the end of the first movement, other measures seeming quotations of the third or first movement, and so on. It’s like a collage of high-profile bits of those two movements, all their major ideas crammed onto one page. So what Ives did, apparently, is start writing a kind of stream-of-consciousness piece, and then go back and focus on the best ideas, and expand and expand and expand from within, sorting out some ideas to one movement and some to another. He used his first-pressing composition as a kind of generator of themes and motives, and then went back and singled out the best ones for extended development.

The First Sonata has more undeveloped sketches to analyze in this respect – I went through more than two hundred pages today – than the Concord does, though the sketches for Thoreau brought me to a similar conclusion. If anyone ever wants to trace Ives’s compositional process from first inspiration to completed score (which is a little outside the scope of my project), the First Sonata’s third movement is a great test case. Ives was able to trust his subconscious to uncritically write a piece of music that had little value or coherence on its own, and then go back and mine it for the best ideas it offered, refining and expanding it again and again. It takes a lot of creative fortitude and not being satisfied with what’s on the page, not even knowing what there is on the page that’s going to turn out to be valuable. Some pretty odd-looking, non-prepossessing musical ideas turn out to be major thematic ones as a result. It’s a creative leap of faith.

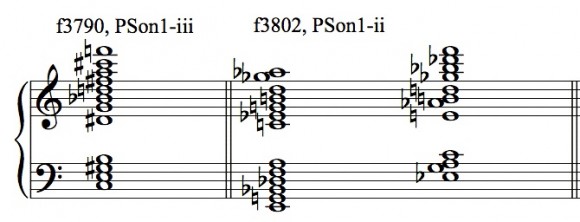

One the other hand, I find things in the mss. that merely taunt me. Ives’s sketches are dotted with large chords in whole notes, many of them comprising all twelve pitches arranged via various-sized thirds or fifths. He often places these chords immediately following a double-bar-line where he’s ended a movement. For instance, here are some chords I found at the end of sketches for the First Sonata’s third and second movements, respectively:

I’ve tried correlating the chords with sonorities from the preceding movement, and gotten nowhere. And had that worked, why would he write the chord after the movement is finished rather than at the beginning? I stare at these chords and send out vibes to the hereafter: “Charlie, you’re trying to send me some kind of message here, but I’m not getting it yet. Can you be a little clearer?”

I call him Charlie now, we’re pretty close.

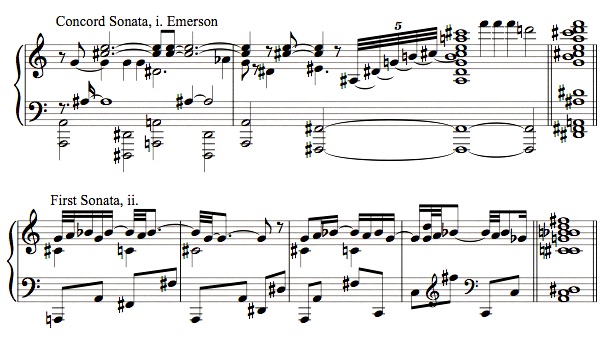

UPDATE: I woke up this morning and the answer was swimming in front of my eyes. I had found it odd that so many of the chords had diminished seventh chords on the bottom, and then I remembered that Ives’s bass ostinatos often jump up and down by minor thirds. Take a look at these two passages:

All the major notes from each passage add up to the chords at the end. That the second example wavers between Bb and B and C# and C in the lower treble fits the paradigm, because some of Ives’s such charts show alternate accidentals for certain notes in the chord. Ives clearly liked to experiment with large vertical sonorities as a way of organizing moments of static texture, often making sure that he didn’t reuse the same pitch in different registers, and as a way of organizing his polytonality with different triads in different registers.

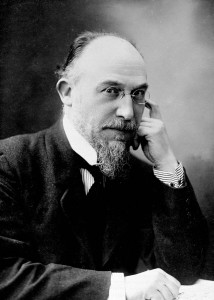

“The Idea Can Do Without Art”

In 1917 as Erik Satie was working on his masterpiece Socrate, he penned a little treatise to which he appended the title “Subject matter (idea) and craftsmanship (construction).†The whole is quoted in books on Satie by Robert Orledge and others, but I don’t find it on the internet outside of scholarly writings, and I think it deserves to be better known:

In 1917 as Erik Satie was working on his masterpiece Socrate, he penned a little treatise to which he appended the title “Subject matter (idea) and craftsmanship (construction).†The whole is quoted in books on Satie by Robert Orledge and others, but I don’t find it on the internet outside of scholarly writings, and I think it deserves to be better known:

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Craftsmanship is often superior to subject matter.

To have a feeling for harmony is to have a feeling for tonality.

The serious examination of a melody will always, for the pupil, be the essence of an excellent harmonic exercise.

A melody does not imply its harmony, any more than a landscape implies its color. The harmonic character of a melody is infinite for a melody is an expression within the overall Expression.

Do not forget that the melody is the Idea, the outline; at the same time as being the form and the subject matter of a work. The harmony is an illumination, an explanation of the subject, its reflection.

In composition, the various parts, between themselves, no longer have connections with any ‘school’. The ‘school’ of composition has a gymnastic aim, nothing more; composition has an aesthetic aim, in which taste alone plays a part.

Make no mistake: the understanding of grammar does not imply the understanding of literature; grammar can help or be held in reserve as the writer pleases and on his responsibility. Musical grammar is nothing but grammar.

One cannot criticize the craft of an artist as if it constituted a system. If there is form and a new style of writing, there is a new craft.

To speak of ‘craft’ requires great care and – at all events – great learning.

Who possesses such learning?

The error arises in that a great many artists lack ideas in general and even specific ideas.

The Masters of the past were brilliant through their ideas, their craft was a simple means to an end, nothing more. It is their ideas which endure. . . .

Become artists unconsciously.

The Idea can do without Art.

Let us mistrust Art: it is often nothing but virtuosity.

Impressionism is the art of Imprecision; today we tend towards Precision.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

According to Orledge (“Satie’s Approach to Composition in His Later Years (1913-24), Proceedings of the Royal Musical Association, Vol. 111. (1984-1985), p. 157), the original French is published as item 37 in Erik Satie: Écrits (réunis, établis et annotés par Ornella Volta), (Paris, 1977), pp. 48-9, and there is some question as to whether the final, more politically immediate sentence belongs with the rest of the text. I was drawn back to it by finding in Satie’s Art vs. Idea an echo of Ives’s Manner vs. Substance.