[click to focus]

Misplaced Destiny

One of the things that surfaced upon cleaning out my mother’s house was a small garment that I apparently wore as a toddler. It has, on the front, a symbol of a football and the letters SMU:

And, on the back, another football and some stitched words:

“Gonna Be a Football Hero.” I was named for Kyle Rote, who was quarterback for Southern Methodist University in the early 1950s. I am as clumsy as anyone I know, sucked at sports, and have never felt at home in the physical world. And my earliest enthusiasms, from an age hardly older than that, were for classical music and poetry. No wonder I grew up such a mess.

Of course, the question that will haunt me now is: If the stitching had read, “Gonna be a microtonal composer,” would I maybe have gone into football?

Even the Most Brilliant Musicians Are Mortal

Death is not taking a holiday. I learned on my way to California that my good friend Martha Herr died on Halloween. She had survived breast cancer twice, and this time succumbed to a brain tumor. She was a phenomenal singer, and though she started out working with the Creative Associates at SUNY Buffalo, she spent the bulk of her career teaching at The University of São Paulo, where she became the world’s leading authority on Portugese diction for singers. She and her then-husband John Boudler commissioned an early work from me, Cherokee Songs for voice and percussion. And I am even more grateful to her for having made a recording for me of one of my best works, Scenario (2004) for soprano and soundfile, based on a wild S.J. Perelman text. I had lost touch with her and hadn’t seen her in years when she started teaching as a sabbatical replacement at Bennington, and she started visiting me; and she spent a day with me in the studio getting Scenario down. I’m hoping to release the piece on a CD next year. She was a lovely person, a consummate musician, and fun.

Death is not taking a holiday. I learned on my way to California that my good friend Martha Herr died on Halloween. She had survived breast cancer twice, and this time succumbed to a brain tumor. She was a phenomenal singer, and though she started out working with the Creative Associates at SUNY Buffalo, she spent the bulk of her career teaching at The University of São Paulo, where she became the world’s leading authority on Portugese diction for singers. She and her then-husband John Boudler commissioned an early work from me, Cherokee Songs for voice and percussion. And I am even more grateful to her for having made a recording for me of one of my best works, Scenario (2004) for soprano and soundfile, based on a wild S.J. Perelman text. I had lost touch with her and hadn’t seen her in years when she started teaching as a sabbatical replacement at Bennington, and she started visiting me; and she spent a day with me in the studio getting Scenario down. I’m hoping to release the piece on a CD next year. She was a lovely person, a consummate musician, and fun.

Upon my return, Peter Gena wrote to tell me that my graduate medieval music history professor Theodore (Ted) Karp has just died. I’ve written about him here before, as my model for the old-fashioned kind of professor who didn’t feel the need to entertain, but whose dignity and generosity made being in his classroom feel like a rare privilege. It was because of him that I always push the music of Johannes Ciconia (c. 1370-1412), who despite his obscurity was, I think, the first great composer, the one who realized things that music could do (echoes, imitation, form through repetition) that no other art form could do. In the class I took with Dr. Karp we pored over every 15th-century music manuscript in detail, though there are probably new ones now that were undiscovered then. I wrote for him a paper comparing the respective Missa Ecce Ancilla Domini’s of Dufay and Ockeghem (a topic he had assigned, characteristically unsexy but therefore all the more challenging); I still refer to it occasionally.

Martha Herr told me a story about working with Morton Feldman that she didn’t want me to publish, and I had promised not to do so during her lifetime (though she was only a few years older than me). She sang the world premiere of Feldman’s opera Neither – that’s how good she was. There is a section in that piece with constant meter changes of the Feldman variety – 3/8, 6/2, 5/4, and so on – that she found impossible to memorize, so she wrote it out on a long strip of paper and attached it behind the footlights onstage so she could read it when she came to that part. One day the conductor, whoever he was, came to her and pointed out that the entire passage could have been made quite simple if one simply remetered it in 4/4. She took it to Feldman, and said, “Morty, you know this really complicated passage would work out just fine in 4/4.” She says Feldman chuckled and said, “Yeah, isn’t that cool?”

A Gentle Rain of Adjectives

My Romance Postmoderne has now been called gorgeous and calming; my suite The Planets has been dubbed weighty and cerebral. I can think of some award-winning composers who would be baffled by at least the second assessment.

Like I Said

In The Atlantic: “Academics, in general, don’t think about the public; they don’t think about the average person, and they don’t even think about their students when they write… Their intended audience is always their peers. That’s who they have to impress to get tenure.†What have I been saying?

How Ives Did it

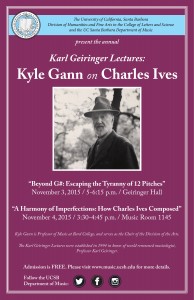

Next week I’ll be in Santa Barbara giving the Karl Geiringer Lectures, named for a famous musicologist who taught there, one (public) on microtonality, and the other (for musicologists) about what we can learn about Ives’s compositional process from his sketches. The latter is mostly about the First Piano Sonata, since we have many more preliminary sketches for that than for the Concord, and there’s really only one page I’m discussing at length: the presumptive first sketch written at Pine Mountain, CT, and dated Aug. 4, 1901. But it’s a fascinating page, an abbreviated and prescient outline for what would become a much longer movement. I’m also relating that at some length to Ives’s discussion of composing in the Essays Before a Sonata, which I think has never been taken seriously enough as a philosophy of what makes music great. When I get back I’ll publish the Ives lecture somewhere on the internet – here, if no more prestigious locale presents itself. I guess the UCSB people decided having a photo of Ives on the poster would bring in more people (or repel fewer) than a photo of me.

Next week I’ll be in Santa Barbara giving the Karl Geiringer Lectures, named for a famous musicologist who taught there, one (public) on microtonality, and the other (for musicologists) about what we can learn about Ives’s compositional process from his sketches. The latter is mostly about the First Piano Sonata, since we have many more preliminary sketches for that than for the Concord, and there’s really only one page I’m discussing at length: the presumptive first sketch written at Pine Mountain, CT, and dated Aug. 4, 1901. But it’s a fascinating page, an abbreviated and prescient outline for what would become a much longer movement. I’m also relating that at some length to Ives’s discussion of composing in the Essays Before a Sonata, which I think has never been taken seriously enough as a philosophy of what makes music great. When I get back I’ll publish the Ives lecture somewhere on the internet – here, if no more prestigious locale presents itself. I guess the UCSB people decided having a photo of Ives on the poster would bring in more people (or repel fewer) than a photo of me.

If you’re in the area, that’s November 3 at 5 in Geiringer Hall for the microtonality lecture, and November 4 at 3:30 in Music Room 1145 for the Ives lecture. I’ve already given the Kushell Lectures at Bucknell, the Poynter Fellowship Lecture at Yale, and the Longyear Musicology Lecture at the University of Kentucky. I just Googled “named musicology lectures” to see if there was a list I should be crossing off somewhere, but nothing came up. Hit ‘n’ miss, I guess.

There’s Doin’s a-Transpirin’!

Gannian events abound. This weekend I’ll be in Philadelphia participating in workshops devoted to performing the works of Julius Eastman, run by the Bowerbird Ensemble. Sadly, my teaching schedule precludes my being there for the opening performance of Crazy Nigger tomorrow night.

A week from Saturday, on Oct. 24, the NewEar ensemble is playing my 75-minute suite The Planets at St. Mary’s Episcopal Church in Kansas City, the first ensemble to do so besides Relache, who commissioned it. Lee Hartman is conducting the piece, which I think is a good idea; Relache did it sans conductor, which is difficult in some movements.

And on November 3 and 4 I’m giving two lectures at UC Santa Barbara, the second one the Geiringer Musicology Lecture. The latter is titled “A Harmony of Imperfections: How Charles Ives Composed.” The first one, for a more general audience, is “Beyond G#: Escaping the Tyranny of 12 Pitches.” These don’t seem to be listed on the schedule yet. Nor have I finished writing them, but I’ve certainly got all the material in my head. Busy times.

UPDATE: I forgot to include a performance of my Romance Postmoderne this Friday in Pasadena by micro-pianists Aron Kallay and Vicki Ray. And I’m a little disappointed no one commented on the Simpsonian provenance of my headline.

Memories of an Early Frost

My mother often told me, and I half-remember it, that when I was a toddler I would listen patiently to her reading poetry for as long as she would do it. It is to this that I attribute my love for writing vocal music. I have always been extraordinarily fascinated by the simple fact that words have their own inherent rhythms without which they can hardly be understood. For me to set words is like setting gemstones, and I always have to choose a setting that makes the sound of the word, not necessarily its meaning, shine to advantage. I know there are other philosophies and methods of text setting, and I don’t disparage them, but I don’t respect them either. Handel and Virgil Thomson are my allies on this point. And the principle was impressed on me by my mother’s voice even before I could read (which was at age four).

My wonderful cousin Ann tells me that as recently as last week my mother recited an entire poem from memory, Emily Dickinson’s “Because I would not stop for death,†on what was virtually her deathbed, following her surgery at Baylor Hospital in McKinney, Texas. The surgery went well, but its aftermath did not. Whether Mom’s funeral, Wednesday, went well was, I suppose, a matter of perspective. The churchly elders who officiated but who hardly knew my mother wreathed her in Christian boilerplate and claptrap that attempted to reduce her to just another devout little old church lady, assuring us that we shouldn’t be sad because she had been welcomed into heaven and was sitting at the right hand of the Father – as though our concern for what she was going through at the moment was uppermost among our anxieties. It was, in bulk, a funeral that would have sufficed for any interchangeable number of old ladies who never missed Sunday school.

My mother was devout and certainly prayerful, and seemed to have become more so in recent years, under the influence, I suspect, of church friends who assailed her from all sides. But she also complained to me that she had to hide from her Baptist friends some of the novels she read, of which they would not have approved. She had an acerbic side and a sarcastic sense of humor, and could manage a sharp tongue. I arranged for some time for the funeral attendees to speak in turn, and at my turn, I rather truculently insisted on reading in its entirety Mom’s favorite poem – “Wild Grapes†by Robert Frost, which she had read to me so many times when I was a boy – even though it was three-and-a-half pages long, even though there were octogenarians standing in the warm Texas sun to wait for me to finish, even though it interrupted the revival-meetin’ atmosphere with a secular intrusion, and with little regard for what her church friends must have thought.

The poem is too well-anthologized and –known to repeat here, but I thought its closing lines were admirably calibrated for ending a funeral:

I had not taken the first step in knowledge;

I had not learned to let go with the hands,

As still I have not learned to with the heart,

And have no wish to with the heart – nor need,

That I can see. The mind – is not the heart.

I may yet live, as I know others live,

To wish in vain to let go with the mind –

Of cares, at night, to sleep; but nothing tells me

That I need learn to let go with the heart.

I read it, as much as I could, with the inflections I remember my mother reading it with. (I can clearly recall, from fifty-five years ago, how she intoned, “I said I had the tree. It wasn’t true. / The opposite was true. The tree had me.â€) My voice broke a few times near the end. I don’t know what kind of spectacle I made of myself; several people did thank me afterward. I wish I could tell her that I did it, that I personalized her funeral by revealing what I most learned from her. I had made, to those who could understand it, the point that my mother was not simply a Sunday-school conformist: she had a brain, and wide literary and historical interests, and she thought for herself, and she did not let the bromides of organized religion occupy so large a space in her life as to divide her from the wider world.

Diffident Leviathan

Accordionist Veli Kujala did a lovely job on my piece Reticent Behemoth for his quarter-tone accordion. Here’s the recording from the world premiere last Thursday in Turku, Finland (duration five and a half minutes). I do love the accordion, and Veli made the piece sound more delicate and nuanced than I could have expected. I’m hoping to write him another piece or two.

Strange Bedfellows

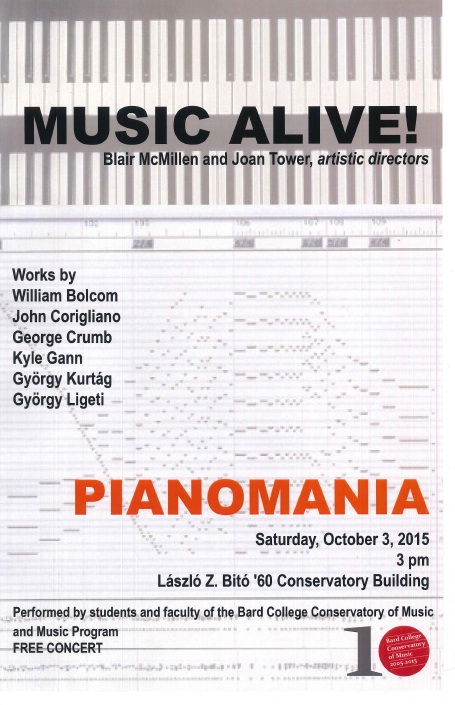

I’ve got a performance coming up at Bard College [where I teach] this Saturday. My office Disklavier will play my Bud Powell homage Bud Ran Back Out, and famous composer Joan Tower, no less, is slated to play the second dance, “Sad,” from my Private Dances. As you can see from the accompanying poster, Kurtág, Corigliano, Ligeti, and I are making a once-in-a-lifetime appearance on the same program. If it weren’t for Crumb and Bolcom I’d feel a little out of place. The MIDI graphic on the poster is a section from my Nude Rolling Down an Escalator, taken from my eponymous CD cover.

I’ve got a performance coming up at Bard College [where I teach] this Saturday. My office Disklavier will play my Bud Powell homage Bud Ran Back Out, and famous composer Joan Tower, no less, is slated to play the second dance, “Sad,” from my Private Dances. As you can see from the accompanying poster, Kurtág, Corigliano, Ligeti, and I are making a once-in-a-lifetime appearance on the same program. If it weren’t for Crumb and Bolcom I’d feel a little out of place. The MIDI graphic on the poster is a section from my Nude Rolling Down an Escalator, taken from my eponymous CD cover.