University of Illinois Press doesn’t allow musical examples in their books (scares off too many prospective buyers, I guess), and so, like so many musicological authors these days, I’m putting my musical examples for Robert Ashley on the internet. I’ve started a Robert Ashley Web Page on which you can see excerpts from Ashley’s scores, hear some brief audio examples, and see a little analysis. Five pages are up now, covering passages from the Piano Sonata of 1959, Perfect Lives, eL/Aficionado, Outcome Inevitable, and Celestial Excursions. I’ll hope to put at least seven more by the time the book appears, which ought to be early next year. Meanwhile, maybe those unfamiliar with or not too sure about Ashley can get their appetites whetted.

University of Illinois Press doesn’t allow musical examples in their books (scares off too many prospective buyers, I guess), and so, like so many musicological authors these days, I’m putting my musical examples for Robert Ashley on the internet. I’ve started a Robert Ashley Web Page on which you can see excerpts from Ashley’s scores, hear some brief audio examples, and see a little analysis. Five pages are up now, covering passages from the Piano Sonata of 1959, Perfect Lives, eL/Aficionado, Outcome Inevitable, and Celestial Excursions. I’ll hope to put at least seven more by the time the book appears, which ought to be early next year. Meanwhile, maybe those unfamiliar with or not too sure about Ashley can get their appetites whetted.

The So-Called Editing Process

I am all in favor of peer-review on principle. Like everyone else I am prone to typos, misplaced bits of information, and unnoticed logical inconsistencies. I am thrilled to have these captured and remedied pre-publication. But in my case, the external reader then invariably goes on to characterize my style as unacceptably “breezy,” “journalistic,” and “colloquial,” which means that my sentences flow well and are varied and to the point, so that the reader doesn’t have to keep slapping himself to stay awake. And if I don’t have enough clout in the matter, they will proceed to gelatinize my liquid paragraphs with the usual academic ambiguities, qualifications, and obscurantisms, until the final product is just as miserable and inedible a porridge as the average musicology screed. Peer-review ought to mean critique by someone who can do it as well as you can. It’s maddening. What is it about a graduate degree that automatically turns its recipient into a lifelong devotee of barren and congealed prose?

Concert Etiquette of the Greats

I’ve been interviewing my good friend Bill Duckworth for an eventual biography or something. He told me about meeting Virgil Thomson in the late ’70s. David Stock was giving one of his new music concerts in Pittsburgh, and Duckworth and Thomson were the featured composers. After the pre-concert dinner, Thomson put his arm around Bill and said, “Young man, don’t take it personally when you look at me during your performance tonight and see that I’ve fallen asleep. If you look at me during my piece, I will be asleep then too.” Bill says, “And I looked at him, and he was.”

During Thomson’s Herald Tribune days, a reader once wrote to him to protest a positive review he had given to an inferior soprano. Thomson wrote back, “I sleep very lightly at the opera, and if anything had gone amiss on stage, I would have awoken instantly.”

Meeting of Minds

The current issue of the journal American Music (Volume 29, No. 1) contains an article by my Serbian musicologist friend Dragana Stojanovic-Novicic titled “The Carter-Nancarrow Correspondence.” It will doubtless be available on the web via JSTOR soon, and if you’re not in academia (we professors can access it for free), a private subscription to JSTOR would be well worth the money; I’d say 85% of the footnotes in my scholarly writing lately are references to articles i’ve found there. Dragana is the person who has gone most thoroughly through Nancarrow’s correspondence, and she has another article in process for Musical Quarterly on his letters to and from Gyorgy Ligeti. I’m urging her to write the first Nancarrow biography, because she’d do a hell of a job, and she’s taught me a lot about his life.

The current issue of the journal American Music (Volume 29, No. 1) contains an article by my Serbian musicologist friend Dragana Stojanovic-Novicic titled “The Carter-Nancarrow Correspondence.” It will doubtless be available on the web via JSTOR soon, and if you’re not in academia (we professors can access it for free), a private subscription to JSTOR would be well worth the money; I’d say 85% of the footnotes in my scholarly writing lately are references to articles i’ve found there. Dragana is the person who has gone most thoroughly through Nancarrow’s correspondence, and she has another article in process for Musical Quarterly on his letters to and from Gyorgy Ligeti. I’m urging her to write the first Nancarrow biography, because she’d do a hell of a job, and she’s taught me a lot about his life.

According to the article, Carter studied Spanish briefly with Nancarrow, who had just returned from fighting in the Spanish Civil War. One of Carter’s first letters to Nancarrow, from as early as 1939, asked about the possibility of his writing a ballet for Lincoln Kirstein’s Ballet Caravan, for which Carter was then music director; obviously this never came to pass. Can you imagine an early Nancarrow ballet? What a wrinkle in music history that would have caused. The letters document aesthetic agreements and disagreements between the two composers. Nancarrow loved Carter’s First String Quartet (which rhythmically quotes Nancarrow, though opinions differ as to where), Cello Sonata, and Double Concerto, but liked the second movement of the Piano Sonata better than the first: “For me the complex rhythms simply don’t sound” (1952). Composer of perhaps the most complex rhythms ever penned, Nancarrow was dismissive of complexity for its own sake, and brought this charge against Messiaen, no less, in 1957: “Messiaen’s music looks complex and sounds even more so, a muddy mess.” (I wonder what he was looking at. Though reclusive, Nancarrow subscribed to all the major new-music journals.) For his part, Carter left Nancarrow “disillusioned” by admitting that he couldn’t understand “by ear” the mathematics of the acceleration canons of Nancarrow’s Study #23, of which the latter had sent an enthusiastic analysis. Nevertheless, for decades Carter expressed warm solicitude for getting Nancarrow’s music out (the longest hiatus in their surviving correspondence was from 1974-87), and in 1968 even invited Nancarrow to come stay with him and his wife in Rome. One is struck by how much earlier Nancarrow could have ventured into the professional world had he only taken advantage of his opportunities. Dragana’s footnotes are among the longest and most detailed in the musicological literature, and she’s an incredible stickler for exactitude of expression. I won’t give away any details yet from the Ligeti article (I help her make her translations from Serbian idiomatic), but it’s, if anything, even more enlightening.

According to the article, Carter studied Spanish briefly with Nancarrow, who had just returned from fighting in the Spanish Civil War. One of Carter’s first letters to Nancarrow, from as early as 1939, asked about the possibility of his writing a ballet for Lincoln Kirstein’s Ballet Caravan, for which Carter was then music director; obviously this never came to pass. Can you imagine an early Nancarrow ballet? What a wrinkle in music history that would have caused. The letters document aesthetic agreements and disagreements between the two composers. Nancarrow loved Carter’s First String Quartet (which rhythmically quotes Nancarrow, though opinions differ as to where), Cello Sonata, and Double Concerto, but liked the second movement of the Piano Sonata better than the first: “For me the complex rhythms simply don’t sound” (1952). Composer of perhaps the most complex rhythms ever penned, Nancarrow was dismissive of complexity for its own sake, and brought this charge against Messiaen, no less, in 1957: “Messiaen’s music looks complex and sounds even more so, a muddy mess.” (I wonder what he was looking at. Though reclusive, Nancarrow subscribed to all the major new-music journals.) For his part, Carter left Nancarrow “disillusioned” by admitting that he couldn’t understand “by ear” the mathematics of the acceleration canons of Nancarrow’s Study #23, of which the latter had sent an enthusiastic analysis. Nevertheless, for decades Carter expressed warm solicitude for getting Nancarrow’s music out (the longest hiatus in their surviving correspondence was from 1974-87), and in 1968 even invited Nancarrow to come stay with him and his wife in Rome. One is struck by how much earlier Nancarrow could have ventured into the professional world had he only taken advantage of his opportunities. Dragana’s footnotes are among the longest and most detailed in the musicological literature, and she’s an incredible stickler for exactitude of expression. I won’t give away any details yet from the Ligeti article (I help her make her translations from Serbian idiomatic), but it’s, if anything, even more enlightening.

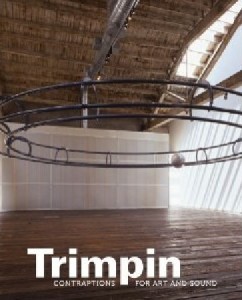

By coincidence, as I was writing this, a copy arrived of the book Trimpin: Contraptions for Art and Sound, compiled and edited by Anne Focke (U. of Washington Press). It contains my article “Trimpin, Nancarrow, and the Transfer of Memory,” along with articles on Trimpin by Charles Amirkhanian, Steve Peters, David Mahler, David Harrington, and others. Along with my Ashley book (which I’m finishing up the final re-edits on), I’ve got three more articles coming out in books this fall: forewords to Ashley’s Perfect Lives and the 50th-anniversary edition of Cage’s Silence, and an article on John Luther Adams’s orchestral music in Bernd Herzogenrath’s book on him, The Farthest Place. I’ve spent the last two years writing like a scholarly madman, and the results are now appearing in quick succession. But this summer: only composing, smoking cigars, and drinking 18-year-old Bowmore. I’ve earned the respite, I’d like to think.

By coincidence, as I was writing this, a copy arrived of the book Trimpin: Contraptions for Art and Sound, compiled and edited by Anne Focke (U. of Washington Press). It contains my article “Trimpin, Nancarrow, and the Transfer of Memory,” along with articles on Trimpin by Charles Amirkhanian, Steve Peters, David Mahler, David Harrington, and others. Along with my Ashley book (which I’m finishing up the final re-edits on), I’ve got three more articles coming out in books this fall: forewords to Ashley’s Perfect Lives and the 50th-anniversary edition of Cage’s Silence, and an article on John Luther Adams’s orchestral music in Bernd Herzogenrath’s book on him, The Farthest Place. I’ve spent the last two years writing like a scholarly madman, and the results are now appearing in quick succession. But this summer: only composing, smoking cigars, and drinking 18-year-old Bowmore. I’ve earned the respite, I’d like to think.

Kiss Off, Purists

Liturgy, the band my son plays in, received an interesting review in the Times today.

Vertiginously Relative

After giving my lecture on Feldman at yesterday’s Feldman festival being presented in Philly by Bowerbird, I spent a half-hour talking to – Feldman’s niece! Feldman’s personality was so universally described as “avuncular” that I told her she must be one of the most effectively uncle-d people in history. She remembered, as a humiliating experience for a 13-year-old, Feldman (and Cage) being booed in 1964 when Leonard Bernstein performed their music with the Philharmonic. And when I told her that I considered her uncle the greatest composer of his era, it seemed to blow her mind. It’s one thing for an artist to face early disapproval and eventually be vindicated, we kind of expect that. But what must that steep trajectory look like to a closely-involved younger family member not in the arts herself? The mind boggles.

Upcoming Appearances

This Sunday at 4:30 I’m giving a lecture on Morton Feldman as part of American Sublime, Bowerbird’s two-weekend tribute to Feldman with performances of several of his most important late works. I come at the end of an all-afternoon series of talks by Feldman experts, of whom I am probably the least knowledgeable – and I know a few things. That event is at Nexus at CraneArts, 1400 N American Street in Philadelphia.

Later in the month, the West End String Quartet will be giving four performances of my Concord Spiral in four cities over two weekends, presented by Rhymes with Opera. The dates and venues are as follows:

Friday, June 17 at 7: Café Orwell, 247 Varet St, Brooklyn, NY

Saturday, June 18 at 6: Windup Space, 12 W North Ave, Baltimore, MD

Friday, June 24 at 7:30: Real Art Ways, 56 Arbor St, Hartford, CT

Saturday, June 25 at 2: Yes!Oui!Si! Space, 19 Vancouver St, Boston, MA

I’m not listed on all the PR materials yet, because Concord Spiral was a late addition to the program (thanks to my old friend Robert Carl). I’ll be at least at the New York performance. Hope many of you can come to some of these.

Call Me a Crazy Uncle

Speaking of criticisms of Ives, I was a little startled to read this in Martin Bresnick’s op-ed in The New York Times yesterday, speaking about the composer Eric Stokes:

Eric was the first “Ivesian†composer I ever met. There were very few of them in those days and there are not many now. I always felt vaguely embarrassed by Charles Ives. I found his music too candid, too forthright. It stuck out like a crazy, opinionated uncle at a polite social event — too unsophisticated for a sophisticated new music audience.

He afterward says “I am ashamed now to recall unspoken, unexamined feelings of condescension I felt toward Ives….” But I imagine that this sums up the way a lot of composers feel about my music as well. Candid and forthright I can only think of as virtues, whereas sophistication, if it is one at all, is one of the minor, almost negligible virtues, way down the list after imagination, vigor, honesty, sincerity, inventiveness, emotiveness, simplicity, integrity, and fifty other qualities.

Oh, I love the Bruckner Eighth Symphony, it’s so sophisticated! – No.

I was just overwhelmed by The Rite of Spring, it’s so sophisticated! – No.

I can’t stop listening to Rothko Chapel, it’s so sophisticated! – No.

The idea that what audiences want from your music is sophistication is a composer’s disease, a neurosis, a lie your grad-school teachers infected you with. To “sophisticate,” says the dictionary, is to cause to become less simple and straightforward through education or experience. And I’m continually trying to shed my education and experience to become more simple and straightforward. Call me a crazy uncle – and don’t invite me to any polite social events!

Repeating Myself

I have often written about the 1989 review in which John Rockwell called my music “naively pictorial,” and the fact that I liked it so much that I’ve ever since adopted “naive pictorialism” as my stylistic moniker. Recently I ran across the 1944 review in Modern Music in which Elliott Carter disparaged Charles Ives’s music as – guess what? – “naively pictorial.” This is company I will gladly keep. I wish Charlie and I could share a good laugh over that one.

I wondered, when I was writing the 4’33” book, whether a renewed involvement with Cage’s music would have any effect on my own. I don’t think it did. But I do think my recent semester spent with the Concord Sonata has had some impact. Most noticeably, I’ve become more open to the idea of re-using material from piece to piece. I could never do it before. I hate repeating myself. I don’t like giving the same lecture twice, I don’t like repeating a class without a long time-lapse in between, and I’ve never been able to re-use material. Even quoting someone else’s music is difficult for me, though I’ve managed it several times. I get into a musical context and I’m feeling my way through it, and the idea of lifting a passage from a previous work or sketch and dropping it in (as Ives did with that Country Band March in “Hawthorne” and so many other pieces) just upsets everything. I don’t seem able to re-say sincerely something I’ve said before. The music leading up to it never quite fits, and I can’t hear the lifted passage as flowing naturally from the preceding new material. I’m amazed Ives could do it. It may come from a habitual tendency toward organicism, which I’ve tried to overcome, since I really don’t think organicism is an essential musical virtue. But if I write a lecture, the first time I read it publicly I feel impassioned; the second time, I feel like I’m lip-synching, like I’m slightly guilty for not having come up with something new to say. Isn’t that odd? As though I change so much with the passage of time that I couldn’t possibly mean the same thing twice (yet all my friends know what a creature of immutable habit I am).

Nevertheless, I have just finished making an orchestral version of the first movement of my Implausible Sketches for piano four-hands. Listening to the piece, I started hearing various lines played by strings, horn, harp, and so on. The piano wasn’t big enough for how I imagined the piece. So I started to orchestrate it. John Luther Adams had just done something similar with a chamber piece of his own, and he told me, “It’ll be a bigger project than you think.” Of course he was right. Starting a new piece from scratch might have been easier, because I wouldn’t have had to spend so much time whittling away at material I had already perfected, and relinquishing assumptions I’d already grown committed to.

First of all, since the Implausible Sketch (first movement: “The Desert’s Too-Zen Song”) was for piano four-hands, it used all seven octaves of the keyboard almost continuously. Some quarter of the music, if not more, would have had to be entrusted to contrabasses and piccolos, which would be ridiculous. The bottom had to be brought up, the top brought down, middle lines subsequently disentangled. Much of the piece has a drone on a low C, and keeping the basses so continuously on that pitch seemed ineffective, if not cruel. I had to reconfigure the piece’s long, long ostinato to let them move around. Then, at eight minutes, the piece seemed too brief for its orchestral incarnation, so I had to perform heart surgery, and move major events further apart. I had to produce three minutes of filler material that didn’t sound like mere afterthought. Repeated-note lines that sounded resonant on the piano sagged in the bassoon. Probably 90% of the piece had to be rethought. I’m still tweaking the details, but I do think I find the result – more simply titled Desert Song – grander than the original.

(To answer your next question, no performance is impending, I just followed an inspiration. But last summer I wrote three string quartets with little hope of performance, and now a friend’s quartet has offered to play them all. One big change in my life is that I’ve quit following Cage’s advice to never write a piece without a performance lined up.)

The only time I’d done something similar before was to base my string quartet Love Scene on the brief third act of my opera The Watermelon Cargo – though I did that because I noticed that I hardly ever had more than four lines going at once. The number of measures and basic content didn’t change, though I did have to make some lines more string-idiomatic. And I’m slowly orchestrating my octet The Planets, though since that has strings, wind, and percussion to begin with, it’s an easier conversion so far. As one gets older, I can imagine that it might be profitable to be able to rely on earlier, more vigorous inspirations. There was certainly a period after 1990 when Nancarrow’s inspiration failed him (he was 78 and had had a stroke after all), and he started pulling out earlier, unused sketches to rework. It does seem a useful part of a composer’s economy to have a cache of previously used or unused material to draw on, and with Ives as a model, I’d like to get over my reluctance.

Part of the problem with orchestration for those of us of a certain age – and it applies not only to writing orchestra music but to working with classical musicians in general – is that some of our music originates in an electronic paradigm. For instance, my “Neptune” from The Planets has a gradually changing synthesizer chord that plays solidly throughout, a kind of cloud from which the other lines emerge. In the orchestra, that cloud will get transfered to the strings. So I find myself wanting to use long, long chords with staggered bowing in the strings, though I had a rather disastrous experience trying this with a subprofessional orchestra in my piece The Disappearance of All Holy Things. I handled it better in Desert Song by having lines move around almost unnoticeably within the cloud. I notice, though, that in Alvin Singleton’s Shadows – one of my very favorite recent orchestral pieces, and there are damn few works I’d apply that phrase to – he keeps the strings holding notes for dozens of measures at a time, and the Atlanta Symphony does a great job with it. It is not very fair, though, to the string players that I want them to be a massive synthesizer. I’d be interested in hearing from others who’ve wrestled with this postminimalist technical dilemma.

Curious Genealogies

My son’s black metal band Liturgy has put out a four-minute video of their song “Returner.” Apparently there’s some big controversy (like father, like son) connected to the fact that they’re “hipsters” playing black metal; Bernard says the fans would prefer that they be wearing bullets on their belts and rusty nails sticking out of their shoulders. I don’t get it. After playing the South by Southwest festival they stopped in McKinney, Texas, and visited my 83-year-old mother. If you knew my mother, you would find the idea of her entertaining a black metal band in her kitchen tremendously enjoyable. Anyway, Liturgy’s new album Aesthetica (on Thrill Jockey – a label I’d actually heard of) got a very nice placement in one of New York Magazine’s “Approval Matrices,” halfway between highbrow and lowbrow and almost all the way towards brilliant.

My son’s black metal band Liturgy has put out a four-minute video of their song “Returner.” Apparently there’s some big controversy (like father, like son) connected to the fact that they’re “hipsters” playing black metal; Bernard says the fans would prefer that they be wearing bullets on their belts and rusty nails sticking out of their shoulders. I don’t get it. After playing the South by Southwest festival they stopped in McKinney, Texas, and visited my 83-year-old mother. If you knew my mother, you would find the idea of her entertaining a black metal band in her kitchen tremendously enjoyable. Anyway, Liturgy’s new album Aesthetica (on Thrill Jockey – a label I’d actually heard of) got a very nice placement in one of New York Magazine’s “Approval Matrices,” halfway between highbrow and lowbrow and almost all the way towards brilliant.

The pivot repertoire that links Bernard’s musical tastes with mine is Brian Eno and the Residents. He came home and we had an Eno-fest last night, both of us singing virtually all the lyrics to all the songs. I doubt that anyone has noticed, but a thesis could be written about Eno’s influence on my music (hint: think Another Green World).

UPDATE: When the band mentioned to my mother the possibility of her coming to one of their concerts, she said, “That would redefine the word ‘anachronism.'”