I actually dreamed this morning that Obama’s secret drone program was really a minimalist sound installation, a kind of soft Phill Niblock piece coming from concealed loudspeakers.

The Difficulty of Seeing Music

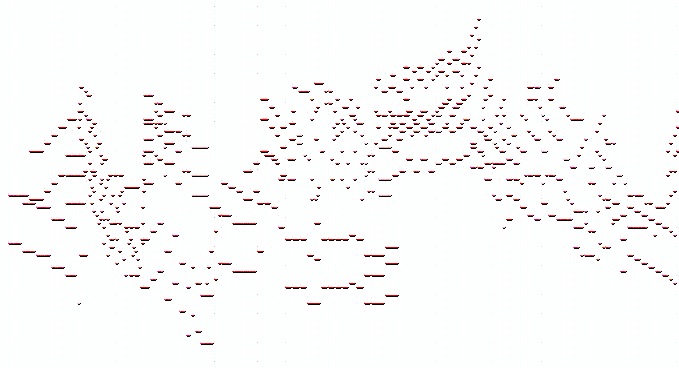

Sort of looks like an old faded-then-digitized photograph of the Alps, doesn’t it? I should make you guess the piece, but given my current obsession it’s too easy. This is the MIDI info, player-piano-roll style, for the first six systems of the Concord Sonata. After the initial wedge motive Ives descends down to the lowest A# on the piano, and then ascends again to the highest G at the bottom of page 1, while the second half of the “Human Faith” theme is isolated, almost visually foregrounded here, in the lower register. Musical notation gives such an inaccurate sense of the use of register that I like to make MIDI charts of passages to get a better sense of pitch-space design – a trick I picked up from Trimpin, who years ago showed me such charts of Nancarrow’s Study #37 (which he had generated, of course, from the piano roll). Sometimes I even look at my own scores this way to get a better sense for improving my overall design. And yet, even this kind of transcription seems misleading, because our eyes make sense of diagonal patterns that don’t exist in music’s strictly horizontal time continuum. You have to imagine a thin vertical line moving across the image from left to right. Still, I did all of “Hawthorne” this way, and learned a tremendous amount about Ives’s use of harmonic stasis in that movement, including things that weren’t nearly as clear in the notation.

Music’s Quasi-Objectivity

Just before writing the Essays Before a Sonata, Ives had read a 1902 article by an Oxford tutor named Henry Sturt, called “Art and Personality.” It’s not a great article, and it’s odd that Ives’s imagination was caught by it, but he quotes it in the Essays more often than he acknowledges. (For instance, the line about the “Byronic fallacy” is Sturt’s, but Ives doesn’t attribute it.) Sturt seems to be building up to some kind of objective criterion to judge art by, but at the end (which is by far the most interesting part) he does a kind of about-face and comes to the disappointing but hardly surprising conclusion that although we feel that our artistic judgments have an objective basis, we can’t reach a basis on which they will be true for all subjectivities. “The popular demand for an objective criterion is strong,” writes Sturt,

but it is not at all clear, and has led to the formulation of some impossible theories… And yet it is easy to see how the belief in an objective criterion has arisen. One source of it is the feeling… that good art has a superhuman backing. It is easy to step from this to the doctrine that you can determine by religion what good art is. This step is unwarrantable… Another source is the practical disciplinary need of having a recognized standard wherewith to put down offenders against artistic good sense… But this practical need must not make us forget that the recognized standard is but a systematisation of personal affirmations. We must not confuse it with the chimera of an objective criterion.

Ives doesn’t quote this part of the essay, but I think he must have had it in mind in writing the end of the Prologue, where the composer calls his inspiration the voice of God and the “man in the front row” calls it “the voice of the Devil.” Ives was clearly wrestling with the fact that he thought his music was really good, and no one else seemed to. It’s something to wrestle with.

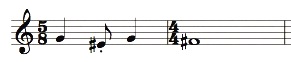

The other day I was composing a piece, and used a rhythm quite common in my music, where the quarter-note beat is interrupted by a couple of dotted-quarter beats:

(This is a microtonal piece, so the G and E# are actually 13th and 11th harmonics of B.) I left it there for a few days, but every time I listened, that third note increasingly seemed too long. I finally changed the meter to 5/8:

and it sounded perfect. I haven’t had a doubt about it since, even though the first version was more aligned to my concept of the piece. It felt as firm as though I had had a math problem with an incorrect answer, and I recalculated and got the right one. It “clicked.” Every composer knows this click, or should. It doesn’t feel as though I simply “liked it better.” Even though there is no objective criterion against which I can measure a phrase in a piece I’m writing, right and wrong answers come up. Because such judgments are made in the right brain, I suspect, there are no words to justify them. When I’m about done with a piece, I put the MIDI version on a CD and play it over and over in my car as I’m driving and – this is the crucial part – try not to listen to it. What happens, as I have my mind on other things, is that every wrong note in the piece jumps out at me and attracts my attention. This works, I think, because when I’m focusing on the piece (with my left brain), I can justify to myself anything I put in it, but with my peripheral (right-brain) listening, things that are wrong become impossible to ignore. My peripheral listening catches the mistakes. My conscious, analytical brain puts these oh-so-clever ideas in, and my intuitive, holistic brain tells me the ones that don’t work.

For me, this is the hardest part about teaching composition. I hear things in my students’ pieces that don’t work, and often I can’t tell the student why they don’t work. The student is looking for reasons and guides and criteria, and all I have is my intuition, which I can’t (as Sturt affirms) transfer into the student’s brain. Often I just have to fix the things that are clearly ambiguous or impractical, and let the student make his mistakes of intuition, hoping that when he hears the piece they will similarly jump out at him some day. We feel that there’s some objective ground here, but we can never prove it. To me it is simply a fact that Mahler’s Ninth is a significantly better piece than Strauss’s Alpine Symphony. If I could be forced to doubt that, then I would have to doubt practically everything. It’s as firm as the periodic table. But we can never establish that as the irrefutable case – which, I guess, is what makes a life in music so frustratingly interesting.

Videos Worth Watching

I’ve always loved David Garland’s songs, and have written about them many times. He’s still making them, and he’s got a new album coming out, Conversations with the Cinnamon Skeleton, that he’s made – believe it or not – with Sean Lennon, supermodel Charlotte Kemp Muhl, and English songwriter Vashti Bunyan. Whew. One song from it, The Long View, is up on Vimeo with a charming animation, pictured here. Even better, David’s moved into my neighborhood, so he’s about the only former denizen of the old Downtown scene that I get to rail against the new world order with.

I’ve always loved David Garland’s songs, and have written about them many times. He’s still making them, and he’s got a new album coming out, Conversations with the Cinnamon Skeleton, that he’s made – believe it or not – with Sean Lennon, supermodel Charlotte Kemp Muhl, and English songwriter Vashti Bunyan. Whew. One song from it, The Long View, is up on Vimeo with a charming animation, pictured here. Even better, David’s moved into my neighborhood, so he’s about the only former denizen of the old Downtown scene that I get to rail against the new world order with.

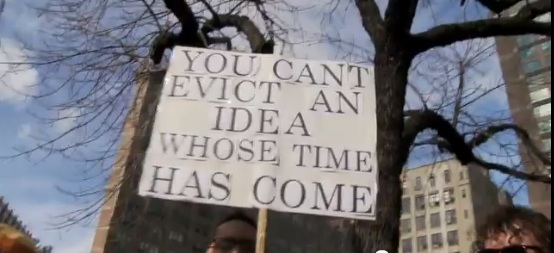

Meanwhile, my son Bernard is hanging out with Downtown drone-bender David First, who was also his guitar and electronics teacher. Together with drummer Greg Fox (late of Liturgy and now in Guardian Alien with Bernard) and vocalist Kyp Malone, they’ve formed a group called New Party Systems, and have been concertizing in support of Occupy Wall Street, an extremely worthy cause. Here’s a video they made about the 99% and featuring some of them, including some of the protesting UC Davis students who agreed to be sprayed with whipped cream. Bernard was helping in the kitchen at Zuccotti Park almost from the beginning. I won’t hear any criticism of the movement, it’s a fantastic thing.

I Am Ralph Fiennes

Not really, but I am a total bardolator. I worked as a security guard in 1978-79, a year I took off between my master’s and doctorate, and while “working” could basically do whatever I wanted as long as I kept my butt in the seat. The two self-improvement projects I completed that year were reading all the Shakespeare plays and analyzing all the Beethoven quartets (by “analyzing,” I don’t mean any more than formal and Roman numeral analysis, but I did get to know them). In the 1980s I watched the BBC productions of Shakespeare on TV, and have since collected all the DVDs, many of which aren’t published for Region 1, so I had to get an all-region DVD player. I collect all filmed versions of the plays except the most Hollywoodish and inept-looking, and I never pass up a chance to see Shakespeare onstage nearby. (My wife works for The Acting Company, which specializes in Shakespeare, so the free tickets are a nice perk.) I have some soliloquies memorized.

And now the media is in a total boil over why Ralph Fiennes picked Shakespeare’s worst tragedy (translate: one they haven’t read) to film, and I seem to be the only person on the planet since T.S. Eliot to hold Coriolanus as his favorite Shakespeare play. My Riverside Shakespeare calls him “the one Shakespeare hero no one can identify with,” or some such, and he’s the character I’ve always identified with most. I have the same overdeveloped superego, the same arrogant feeling that having accomplished something I shouldn’t have to go sell my accomplishments, the same churlish impulse that if not appreciated I’ll pick up my marbles and go elsewhere. I particularly thrill to the lines:

Better it is to die, better to starve,

Than crave the hire which first we do deserve.

Why in this woolvish toge should I stand here,

To beg of Hob and Dick, that do appear,

Their needless vouches? Custom calls me to’t:

What custom wills, in all things should we do’t,

The dust on antique time would lie unswept,

And mountainous error be too highly heapt

For truth to o’er-peer. Rather than fool it so,

Let the high office and the honour go

To one that would do thus.

And I guess it explains why I am, to so many, a similarly unsympathetic character (even though – paradox of my life – a total populist in my own music). (Yet perhaps it’s not a paradox at all, perhaps populism is my version of fighting to defend Rome, the good deed for hoi polloi that I misguidedly expect to be thanked for.) But Coriolanus is a great, taut, spring-wound play about the inability of a brilliant introvert to negotiate society’s petty demands, and I find it comical and revealing that the world seems so antipathetic toward it. Will sent me and my kind a love letter by writing that one.

While I’m at it, my favorite Shakespeare comedies are also unpopular choices: the darkly nihilistic Troilus and Cressida and Timon of Athens, which will add to my curmudgeonly bonafides. [UPDATE: Oops – just realized Timon is a tragedy. I just think of Apemantus’s sardonic jesting, like Thersites in Troilus.] I’m not a big Lear fan, I have to confess: too gruesome and painful. But while I used to think that all copies of Titus Andronicus should be burned, I learned upon seeing film versions of it that it’s less horrifying to watch than it is to read, and one’s sympathies actually get caught up in it. The one play I can hardly stand now is A Winter’s Tale: Leontes just seems too mentally ill to take seriously. Hamlet I love, of course, and am fond of Pericles and Cymbeline, but the ones I watch over and over in sequence are all the consecutive histories from Richard II to Richard III, even the watery three parts of Henry VI included (“tiger’s heart wrapped in a woman’s hide!” – and that’s not even Joan of Arc). Haven’t seen the Ralph Fiennes Coriolanus yet – only because it hasn’t yet hit a theater in my neighborhood.

Wonkish

A repeated criticism that I get for my writing is that I am inconsistent in the level of expertise I assume in the reader. For instance, many people who don’t know much about music assume that musicians always get paid for their work (hah!), and so their first response to 4’33” is that Cage got paid for not doing anything. In my book on 4’33”, it was well worth taking one paragraph at the beginning to dispose of that objection, rather than let it stew unresolved in the minds of the uninformed. On the other hand, I indulge a bit of technical analysis on the Cage String Quartet at the end of the book. And so a few academic critics took umbrage that I was writing for the general public at the beginning, and for experts at the end – I couldn’t decide who my audience was! My editor at the Village Voice taught me that if I wanted to present technical information, to save it for the last fourth of the article – anyone who’s read that far, he said, is not going to stop reading just because one paragraph goes over his head. I found that excellent advice, and it worked for the 4’33” book as well. The couple of pages of technical analysis are in the fifth of six chapters, and I never heard of anyone who stopped reading at that point. As a professional writer, I’m trying to reach as many people as possible. Academic writers, of course, gain more prestige the fewer people are capable of reading them, and so they criticize me, the professional writer, for not aiming my discourse at as narrow a sliver as possible.

And now, in my book on the Concord Sonata, I’m deliberately and intentionally doing it again. Some chapters will be wonkish and readable only by trained musicians, and some will be general interest – since I know how to make even general interest material interesting to the experts, and sometimes how to make wonkish material entertaining for the novices. And once again, in the “peer”-review process, and in reviews afterward, the academics will criticize the professional writer for casting too wide a net (as well as for my “breezy, casual, journalistic” style). I can feel it coming, and there’s no side-stepping it. Fuck ’em.

Excerpts from Outer Space

Here’s a You Tube trailer for John Sanborn’s video to my piece The Planets. The images are from all different movements, but the music is all “Mercury.” The film will be featured at the Videoformes festival in France March 14-18. Relache will begin touring with it in the fall.

Here’s a You Tube trailer for John Sanborn’s video to my piece The Planets. The images are from all different movements, but the music is all “Mercury.” The film will be featured at the Videoformes festival in France March 14-18. Relache will begin touring with it in the fall.

Warning: Self-Obsessed Post

I have nothing to say, and I’m not saying it. Or rather, I do have things to say, but not in this format for the moment. I am beginning my sabbatical, and withdrawing from the world somewhat to work on two of the most ambitious projects of my life. The more immediate is a long (hour-plus) work for three retuned Disklaviers. This will give me the opportunity, for the first time since Custer and Sitting Bull (1995-99) to combine my two great obsessions, the completely free-sounding rhythms of multitempos, and the free-sounding pitch space of microtones. (And even in Custer the rhythmic aspect was somewhat limited by performance requirements.) I tried to start the three-Disklavier piece last year, but I had initially come up with a terribly complicated scale, based on some idea of encompassing seven tonalities. I spent much of the month of August devising a better scale, and I’m finding the one I came up with (which I shall detail at a later date) extremely elegant. And according to my conception of microtonal music, if you get an interesting enough scale, you can just explore all the inherent possibilities of that scale, both the ones you built into it and the ones that appear unexpectedly, and the piece practically writes itself. In fact, all music, I insist, is the exploration of a tuning, which is why the 12tet repertoire has become so tired.

I haven’t mentioned this project partly because, based on my experiences last year, I was afraid it might prove beyond my conceptualizing ability. I’ve used as many as 37 pitches to the octave before, and here, by the fact of three pianos, I have 36. But generally, due to MIDI limitations, I only have three or maybe four octaves of pitch space, and here I have a full seven, 264 different pitches in all (88 x 3) if you disregard octave doublings! And I was having a terrible time, with the old scale, remembering which pitches were on which piano! A triad might be made up of one pitch on Piano 1, another on Piano 2, and a third on Piano 3, and there was no way to simply play a chord progression and judge its effect, I’d have to laboriously assign each pitch to the right piano and listen to them, like composing with some awkward prosthesis. But the new scale is so logical, though with a few quirks (which of course become the most playful aspect of the piece), that, after having written 15 minutes of the music, I now have the scale firmly in my head, and it’s just like composing any other microtonal piece; almost easier than most of mine, in fact, since each octave on the pianos is the same pitches as every other octave, which isn’t usually the case in my MIDI pieces.

Plus, the virtue of the scale is that it is organized such that the three pianos can be played as three separate tonalities – or, they can all be integrated into an overtone series on the central tonic of B-flat (which is not to say that, as in The Well-Tuned Piano, all the pitches are harmonics of the tonic). And I am having the time of my life exploring something that I’ve always wanted to try: just-intonation polytonality. There is a little bit of it in the “Sun Dance” movement of Custer, and I’ve got passages of 12tet bitonality in Long Night, War Is Just a Racket, and Kierkegaard, Walking, but nothing compared to what I’m able to do here. As a teenager, I was absolutely enchanted with the bitonal music of Darius Milhaud, and for decades I’ve been meaning to get back to exploring that effect. I find it difficult to pull off charmingly; Milhaud was ingenious at it, and also had an influence in that respect on Philip Glass, whose music, as he’s shown me, contains more bitonality than people suspect.

Polytonality would seem to be theoretically precluded by just intonation, in which every pitch is defined in relation to a single 1/1 tonic – thus the facile, inaccurate joke so many uninformed composers make about all of Partch’s music being in the key of G. (Might as well say all orchestra music is in A because they tune to the oboe’s A.) But in this case I have enough pitches for three separate tonalities, which, with the right relationships emphasized, can be reinterpreted as more distant reaches of a central tonality. As light can be measured either as a wave or as a particle, so the harmonies in this piece can seem incommensurably unrelated, like random pianos not tuned to each other, or as more complex harmonies in a single spectrum – and I have a continuum to move along between those extremes. It’s a fascinating way of working. And in addition to that I can set the different tonalities at different tempos, slicing up the audio surface in two dimensions at once. What I’m hearing is stretching my ears in a way they’ve never been stretched before. Maybe I’ll write a great piece, maybe a dull one, but I don’t think anyone has ever before done what I’m doing – and how many people would know better than I?

The other project will be a book on Ives’s Concord Sonata. Here again I’ve got plenty of ideas and new information, including things in the sketches that have changed my conception of how Ives wrote the piece. Musicologists have written a ton on the Concord, mostly picking out musical borrowings, both real and (in my view) imagined. But no composer has written about it at length, and no one has really attempted a harmonic or formal analysis; I’m convinced I can do it. I think I’ve figured out what harmonic plan Ives had in the back of his head. But again, it might be years before the book comes out, and I don’t want to publish details here that others might be able to get into print before I can. So it’s the depth and breadth of my projects, rather than any lack of activity, that makes blogging about them inadvisable. I don’t know why it is that my psyche seems to need to veer back and forth between creative work and scholarly work, but it is the case. They feed each other. It may seem bizarre, and it is certainly sometimes self-defeating, but it’s who I am. Perhaps that’s what I have in common with Ives, who insisted that his insurance work informed his music and vice versa.

In other news (and there seems to be less news in my life at the moment than at any time I can remember), composer George Tsontakis has made me one of his “affiliate composers” at his publishing company Poco Forte Music. At the moment the position is merely honorary, but it may result in my (self-)publishing some nicely bound editions of my scores. Nothing could be a clearer indictment of the contemporary music publishing business than that a composer as successful in the orchestral world as George is would withdraw from it and begin self-publishing. I asked for some orchestral scores for Christmas, and the only ones that were “backordered” and didn’t arrive were by a living composer – two symphonies by William Bolcom. Now why is it, that I can order symphonies by someone as widely honored and performed as Bolcom, and his publisher can’t simply mail them to me? Was there a rush on them? Bolcom symphonies a hot Christmas item? Featured on Oprah? It’s a rotten business. To sign up with a classical music publisher these days is a fool’s vanity.

More personally, I had cataract surgery a few weeks ago, and can finally see the world in focus again. Happy new year.

Unnoticed Milestone

Twenty-five years ago this week my first Village Voice column appeared.

The Blind Alleys of Criticism

A particularly invidious form of comparison arises when critics appoint themselves to the rank of H[er]. M[ajesty’s]. Customs and Excise officers whose function it is to spot composers smuggling contraband ideas from one work to another. To ask a composer if he has anything to declare while he is busily unrolling his music to public view is not a very intelligent question. Each act of composition is a declaration. If it did not owe something to somebody it would be intelligible to nobody. Elgar may be said to have “smuggled” the closing pages of Tristan into the final bars of his own Second Symphony. But the comparison is so obvious only a bad critic would make it; and only a fool would “devalue” the Elgar as a consequence. The likeness sheds no light whatsoever on the respective “value” of either work. The way pieces resemble each other is the least interesting thing about them. It is one of musical criticism’s blind alleys.

-Alan Walker, An Anatomy of Musical Criticism, p. 8

I found this thoughtful little 1966 book at a used bookstore in Hudson over the weekend. I often buy books about music criticism and its history. It’s an important topic, and not enough is written about the activity itself. We ought to teach music criticism intelligently and discuss its principles, but instead we let people stumble into it and make up their own rules, which usually turn out to be stupid ones, with the result that what ought to be a prestigious discipline is generally a rightly despised one. As a former critic, I sometimes toy with the idea of writing something lengthy about the topic myself, although interest in it seems more in decline than ever.

Walker – better known today for his superb three-volume biography of Liszt – argues compellingly that music criticism should be placed on an objective basis, not via the old-fashioned route of coming up with rules for how music supposedly works, but by beginning with our collective ability to identify with some pieces more than others, and explicating our perceptions of why the music elicits our sympathies so strongly. At the same time he sets this principle against the observed fact that tastes do change historically, and that audiences do “catch up” with composers who seem outrageous at first – and sometimes move past them. He is a little too impressed with Rudolph Reti’s The Thematic Process in Music, which was popular in the 1960s but which has come in for its own share of debunking, despite some undeniable insights. But he also develops a principle that is central to the way I teach composition. Giving many successful and unsuccessful examples, he writes about how a music idea can be given an utterance that does or doesn’t completely express it in its clearest form. He goes on,

The very act of teaching composition is a tacit acknowledgement that you can not only diagnose a distinction between “idea” and “utterance” but that you can also remedy the situation. A good composition teacher does not merely re-compose his students’ work. He helps them to search for its truer expression. It is his chief function to help his students to keep re-formulating the “utterance” until they have captured the “idea.” (pp. 72-73)

This is exactly how I think about my students. I don’t mind my students writing in any style they want to (right now I have one student writing rock songs, one neoromanticist, one mystical pandiatonicist. and one postminimalist). Nor do I push them, as so many colleagues I know do, to write “20th-century music,” whatever that is, since the 20th century is over and we’re in a pluralist situation. Instead I push them to isolate the idea or ideas most important to them and make the expression of those ideas so clear that the listener can’t help but grasp what they are. And I help them steal solutions from other music, reminding them, in effect, that if their music “did not owe something to somebody it would be intelligible to nobody.” Most bad music today, I think, is bad not because its ideas are weak, but because the composer doesn’t work hard enough to find the perfect, clearest expression of those ideas; in fact, there seems to be a general reluctance to say outright what one means, preferring to hedge one’s bets and clutter the musical surface with obfuscating bells and whistles. If I ever teach criticism again, I could do worse than Xerox and assign Walker’s little out-of-print book as an attempt to find an objective starting point, with a route that leaves the blind alleys behind.