Rock Happens, my review of the recent concert of Barbara Benary’s music by the Downtown Ensemble and Gamelan Son of Lion, is now up at the Village Voice. (By the way, her name rhymes with “plenary,” not “canary” – confirmed it herself.)

Kyle Gann on music after the fact

Rock Happens, my review of the recent concert of Barbara Benary’s music by the Downtown Ensemble and Gamelan Son of Lion, is now up at the Village Voice. (By the way, her name rhymes with “plenary,” not “canary” – confirmed it herself.)

Postclassic Radio has been found in violation of the 1998 Digital Millennium Copyright Act, under which Live365.com operates. Because I sometimes play more than two consecutive tracks from the same CD, the station cannot be listed in Live365’s directory – I don’t really know how big a deal that is, I imagine most of my listeners go there direct from this blog. But here’s the e-letter I sent to Live365:

Dear Live 365 Staff,

I see that my internet station, Postclassic Radio, is

listed as noncompliant due to too many tracks coming from the same CD. I

run a classical-paradigm station, on which I sometimes play multimovement

works. According to the rules you’ve set up, it would be inadmissable to

program an entire Beethoven symphony, because that would require four

consecutive tracks from one CD. Surely some exception could be made for

classical works with more than two movements? My station gives exposure to

hundreds of little-known composers who are thrilled that I do this for

them, and some have specifically thanked me for playing entire works,

something no commercial radio station will do any longer.I submit that this ruling imposes an unfair penalty on classical music. It

should be easy to distinguish multiple tracks that are all from one

classical work from several independent tracks that are truly

noncompliant: the titles will all be the same. For instance, I am now

listed as noncompliant for having a piece by Julius Eastman called “Piano

2,” which is in three movements, and the tracks are labeled “Piano 2,

i,” “Piano 2, ii,” and “Piano 2, iii.” In addition, this

is a private

recording, not even commercially released. No one is losing any income

from my playing this little-known, unrecorded work. Isn’t it possible that

when several consecutive tracks have the same title, except for the

movement number – like “Symphony No. 5” – that some allowance could be

made for it being an integral classical work in several tracks? And how is

it possible for this ruling to apply to works that aren’t even

commercially recorded, and therefore aren’t “tracks from the same CD”

in any meaningful sense?My station attracts a lot of national attention, and there will be some

public outcry if I have to start scaling back the complete works I play

because a pop paradigm is being imposed on classical music.Thanks for your attention, etc.

I won’t quote the reply I received, because I didn’t ask permission, but it sort of politely said, Screw you. Here’s a statement from their original notice:

In 1998, Congress passed the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA). This piece

of legislation established parameters around which one could build a

business in instances where copyrighted digital material is concerned (e.g. music,

software). It also built in some protections for the content

companies who produce said digital material, (e.g. the RIAA) as they wanted to

ensure that internet distribution wouldn’t cannibalize sales.

So here I am, paying 30 bucks a month for the privilege of giving my friends’ music away so they can get some exposure, and I’m prevented from doing even that in a way that represents their music correctly because of laws put in place to protect megacorporations from being ripped off by the masses. One can imagine a nearby future in which people will not be allowed to distribute their music to each other unless some corporation is skimming money off the transaction.

Speaking of harmonies that draw specific sources to mind, my friend Bob Gilmore thinks that Morton Feldman ruined the interval of the falling minor seventh – not that it is no longer beautiful, but that using it has become an instant signal of Feldman influence.

Personally, I tell all my students to steal what they want and not worry about their influences showing through. For all they know, their music may be better known a hundred years from now than that of the people they’re stealing from, so they might as well plan for that optimistic eventuality.

Like clockwork, every November of an odd-numbered year I end up teaching Messiaen’s Quartet for the End of Time. And we get to the gorgeous fifth movement “Louange à l’éternité de Jésus†(which I helpfully translate for the students as “Lounging through enernity with Jesus,†using the Spanish “Hay-zeus†pronunciation), and I wonder once again why so many commentators have taken Messiaen to task for using the so-called “added sixth†chord, E-G#-B-C#. Here’s Paul Griffiths on the subject:

There is a discontinuity of taste as well as period…. [T]here comes a little tune of banal perkiness in the “Intermède,†and in the two “Louanges†music that many of Messiaen’s stoutist adherents have found regrettable or else passed over in silence. For not only do the added-sixth and diminished-seventh chords appear at crucial moments and in profusion, but the atmophere is that of the sentimental piety exuding from such similarly scored movements in the French repertory as the “Méditation†from Thais….

This is not to say that Messiaen consciously wrote vulgar music for his two adagios. On the contrary, he has maintained with some fierceness that they are not vulgar at all…. However, a musical sensibility that can form such an opinion is awesome indeed: it takes a sublime, even saintly naïvité to accept materials from Massenet and Glenn Miller, then use them to praise Christ as if they had never been employed for any baser purpose. But this is Messiaen’s way, and though the two “Louanges†offer the greatest stumbling block to the sophisticated, in so doing they only exemplify in extreme fashion a refusal of discrimination typical of Messiaen’s art.

I’m glad to think that Griffiths will think that my musical sensibility is awesome, for I don’t understand what’s wrong with the added-sixth chords at all (nor even the diminished chords, which in the fifth movement are only triads, not sevenths, and which only occur in one transitional measure). Messiaen uses the chord, here and also in the Turangalila Symphony of a few years later, as an ecstatic, sensuous resolution chord, and I find it sublimely perfect for that purpose. Of course there was a period in the swing era in which the added-sixth chord was a standard closing for evergreens and showtunes. So what? What about that invalidates it for use in any other context? The way I see it, the 19th century from Chopin on routinely substituted the third scale degree for the second in a dominant seventh – that is, in the key of C, using G-F-B-E (reading upward) instead of G-F-B-D. To use the sixth scale degree in the tonic triad strikes me as the logical equivalent. Why is such a substitution justified in the dominant (assuming one holds no brief against Chopin), and not in the tonic? It sounds lovely; when I hear it in swing era jazz it reminds me of swing era jazz, and when I hear it in Messiaen, it sounds quite different in context, and reminds me of Messiaen. Yet Griffiths is hardly the only writer to take fierce exception to it.

I have never been able to fathom this mentality that attaches some specific element of music to a certain time and style and thinks it should be buried with that time and style. It seems like a type of insensitivity, an inability to hear sounds in their momentary context. Isn’t it obvious that it’s not what materials you use that counts, it’s what you do with them? In high school I had a composition teacher who wouldn’t allow me to use the chromatic scale because it had 19th-century connotations. I’m happy to report that I have made profitable use of the chromatic scale many times since. I’ve defended a lot of my favorite Downtown music that uses synthesizer from people who say that music with synthesizer reminds them of ‘80s rock, as though that were the most heinous grievance with which a piece of music could be charged.

So, doesn’t the harpsichord sound like 1770’s chamber music? Doesn’t the oboe sound like French Romanticism? How can a timbre, or a harmony, or even a rhythm, so take on the imprint of one era that no one can ever be allowed to use it again? Since Harry Partch used the 11th harmonic, should I abstain? Stravinsky used the octatonic scale, should I leave it alone? And yet, Webern became intimately associated with the major seventh, and for decades afterward, hundreds of composers seemed willing enough to remind the listener of Webern. This guilt-by-association of harmonies and timbres always seems awfully selective, as though the real point is to impress the listener with what company you keep: Webern gooooood, Glenn Miller baaaaaaad. I guess I’m just happy that I’m not sophisticated in Griffiths’s definition, because that much less music is a stumbling block to me.

I’ve also never understood why some people find certain passages in Mahler’s music “vulgar.†Maybe I’m just not very refined.

Opening bars of John D. McDonald’s Kyle Gann in Worcester:

Now up on Postclassic Radio, along with new works by Amy Kohn, Belinda Reynolds, Alvin Singleton, Mason Bates, and Jo Kondo.

One of my cherished self-indulgences is to read each new Gabriel Garcia Márquez novel as it comes out, and he has never disappointed me. His new Memories of My Melancholy Whores, however, contains this startling sentence:

At noon I disconnected the phone in order to take refuge in an exquisite program of music: Wagner’s Rhapsody for Clarinet and Orchestra, Debussy’s Rhapsody for Saxophone, and Bruckner’s String Quintet, which is an endemic oasis in the cataclysm of his work. [Italics added]

Do the Colombians know something about Wagner that we don’t? Is there a South American Wagner who isn’t Richard?

Actually, this reminds me of the entrance exams I took to start my Master’s at Northwestern. There was a question on the exam: “Debussy wrote chamber music involving the following instruments:”, and then were listed some pairs of instruments. The only answer at all applicable was “flute and saxophone,” and I knew about Debussy’s Syrinx and Sonata for Flute, Viola, and Harp, but I was pretty certain that he had never written a piece of chamber music using saxophone. So after I was done, I went up and argued with the instructor, Theodore Karp, who later became an important mentor of mine. He claimed there was some chamber arrangement of an orchestral piece with saxophone. Grove Dictionary of Music, as I quickly ascertained, lists no saxophone music among Debussy’s chamber works, but if you rummage around through the orchestral music, there is indeed a piano reduction of his Saxophone Rhapsody mentioned as having been made by one Roger-Ducasse. Even so, that was an awfully obscure bit of repertoire to ask incoming master’s students to know about. It turned out, of course, that if you didn’t pass the test you had to take a remedial course, for which privilege the school charged you an extra $3000. I was the only incoming student that year who passed, and my doctoral exit exams, six years later, were easier than the entrance exams. Ever since I’ve been dubious about grad-school entrance exams, as potentially having more to do with making money for the school than testing worthwhile bodies of knowledge.

Ethan Iverson, himself the rather incredible young jazz pianist of Bad Plus, wrote about my CD Nude Rolling Down an Escalator for Downbeat magazine. (Geez, how hip can I get?) Not content to leave the review there, he’s blogged it here. Not only that, he mentions another mention that I got from blogger Alex Ross. This is getting blogtastic!!

During Bard’s Janacek festival a couple of years ago, I became rather impressed with that composer’s textural and tonal originality, especially upon realizing that I had always thought of him as a 20th-century composer and he was actually born in 1854. So awhile later, browsing at Patelson’s in New York, I ran across the sheet music to Janacek’s On an Overgrown Path – the piece that the well-known eponymous blog is named for, I suppose – and picked it up. It sat on my piano for months, but since I moved to a new house, my Steinway has developed a terrible case of sticking notes, rendering it unsatisfying to play, and piano tuner time is at a dear premium up here. So at an odd moment I finally decided to listen to the new ECM recording of the piece with András Schiff while following the score. It’s a lovely recording – except that Schiff can’t handle the 5/8 meters that come up in a couple of movements. He plays this passage:

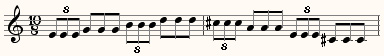

by speeding up the first three 8th-notes notes and prolonging the last two (even extending the left-hand D-flat into a quarter-note), turning the meter into a more conventional 6/8, as you can hear here, and disappointingly taking the edge off of Janacek’s rhythmic originality. (In fact, when the music reverts to 2/4 in the 5th measure, Schiff’s 8th-note suddenly slows down by 50 percent, making it clear that he was feeling the 5/8 as 2/4 with triplets all along.)

This wouldn’t merit mentioning if it weren’t so common. Classical musicians are taught early in life that a measure is a rhythmic unit, divided into two or three parts, and if divided into more, then divded according to a symmetrical heirarchy: 2 groups of 2, 2 groups of 3, 3 groups of 3, and so on – or not and so on, because that’s about it. Of course, quite early in the 20th century – On an Overgrown Path is a hundred years old – composers opened up a new conception of meter, as a quantity of equal or even unequal units. Musicians accustomed to playing composers as long-dead as Stravinsky and Copland are used to negotiating 5/8 and 7/8 meter, but it’s surprising how many professional musicians have never added the new paradigm to their repertoire. They recognize it and think they know how to do it, but when they start to play, their body-need for a regular beat, like Schiff’s, overrules their visual cognition. I have to warn my students, some of whom gravitate to 13/16 and similar meters under the influence of notation-software-induced ease, that some classical players will have to be taught how to play the rhythm, and that they might not be teachable. Recently a student wrote a passage in 10/8 meter, with the following quite elegant rhythm that required four beats per measure, quarter-notes on 1 and 3 and dotted quarters on 2 and 4:

It seemed perfectly simple to him and me, but the performance, by professional players steeped in 19th-century music, was a disaster. They ended up speeding the non-triplet 8th-notes into triplets, and making it a kind of bumpy 4/4. No amount of pleading could get them to feel successive beats as unequal.

I face the same mentality when I show people my Desert Sonata for piano, which has a long moto perpetuo passage in 41/16 meter. Certain people look at it and exclaim, incredulously, “How do you COUNT that?!” Well, of course, you don’t count it, but if you will play the 16th-notes evenly and in the order indicated, I promise it will come out all right. What they want, of course, is some heirarchical division of 41 that they can funnel all those 16th-notes into, and there just isn’t one. (Please don’t be tiresome and advise me to renotate it in 4/4 – the 41/16 clarifies the underlying isorhythm, and mangling it into 4/4 would turn it into an unmemorizable mishmash.) By now this new metric paradigm is very common among young composers – Sibelius notation software will handle meters up to 99/32 just as easily as 4/4 – and so it’s astonishing to still find it so missing in classical music pedagogy. In 1947 Nancarrow turned to the player piano because the musicians he met couldn’t play the comparatively simple cross-rhythms he was writing. Were he to come back today, there are circles in which he would find that things haven’t improved much.

In his [1938] essay, “Paleface and Redskin,” the literary critic Philip Rahv claims that American writers have always tended to choose sides in a contest between two camps the result of “a dichotomy,” as he put it, “between experience and consciousness…between energy and sensibility, between conduct and theories of conduct.” Our best-selling novelists and our leaders of popular literary movements, from Walt Whitman to Hemingway to Jack Kerouac, number among the group Rahv called the redskins. They represent the restless frontier mentality, with its reverence for the sensual and intuitive over the intellect, its self-reliant individualism and enthusiasm for quick triumph over obstacles….

While the redskins took to the open road, jotting down their adventures along the way, the palefaces tended to congregate in the cities, where they drew heavily on European literary and intellectual traditions. They put at least as much stock in the value of artistic transformation and intellectual reflection as they did in capturing the raw data of the emotions and senses for their portrayals of human experience. James and Eliot would be leading figures among the palefaces. Both of them eventually left America, a society that they came to regard as crude, to spend the balance of their lives in England.

Of course, it would be entirely illegitimate to make any such distinction in the history of American music. No no no no no no no. Music is just music, and we shouldn’t try to draw distinctions within it. American music is just anything American composers do. Because I said so, now shut up and practice your scales.

(In other words, the above is basically what Peter Garland and I and a few others have been saying about American composers forever, to an answering, contradictory chorus of anti-intellectuals who don’t believe any distinctions should ever be drawn.)

A week from tomorrow, Saturday, December 3, the Other Minds festival is holding a “musical séance” at San Francisco’s Swedenborgian Church, 2107 Lyon Street, at 2pm, 5:30pm and 8pm. The idea is to raise up the spirits of composers from the experimental (or rather, Postclassical) tradition such as Cage, Nancarrow, Cowell, Crawford, Satie, and Rudhyar. I’m not projected to be dead yet myself by that time (unless they know something I don’t), but nevertheless  their star pianist Sarah Cahill (pictured) will play a piece of mine, “Saintly” from my Private Dances, along with works by others from the still-kicking set like John Adams, Terry Riley, and Mamoru Fujieda. There will also be some works for Disklavier presented, including a new work by Daniel David Feinsmith, my own Nude Rolling Down an Escalator, and a couple of Nancarrow’s Player Piano Studies. Sounds like one of those great San Francisco new-music marathons, with Cahill featured throughout (both my pieces are on the 5:30 concert). Wish I could say I’ll see you there, but I’ll be in upstate New York, kicking myself for not having moved to California right out of college like I was tempted to.

their star pianist Sarah Cahill (pictured) will play a piece of mine, “Saintly” from my Private Dances, along with works by others from the still-kicking set like John Adams, Terry Riley, and Mamoru Fujieda. There will also be some works for Disklavier presented, including a new work by Daniel David Feinsmith, my own Nude Rolling Down an Escalator, and a couple of Nancarrow’s Player Piano Studies. Sounds like one of those great San Francisco new-music marathons, with Cahill featured throughout (both my pieces are on the 5:30 concert). Wish I could say I’ll see you there, but I’ll be in upstate New York, kicking myself for not having moved to California right out of college like I was tempted to.