Brian McLaren sent me this:

I love how the piano keys run out to the very edge of the piano. And end on E.

Kyle Gann on music after the fact

Brian McLaren sent me this:

I love how the piano keys run out to the very edge of the piano. And end on E.

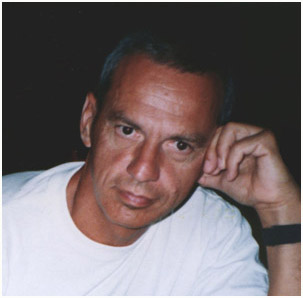

I’ve been posting way too many photos – probably more of you have already seen Yurp than I imagine – but I couldn’t resist this image of John Luther Adams (front) listening to his Veils and Vesper installation at the Muziekgebouw:

It was a fantastic space for it, high-ceilinged and well insulated from other spaces despite its openness, and surrounded on various sides by wood, concrete, metal, and glass – tieing in conceptually, in that respect, to John’s percussion music, which groups instruments via those categories. Walking among the different loudspeakers, you got a strong sense of each veil giving way to the next, like wandering through a series of waterfalls. I wish I could post a soundfile for you, but the music occupies ten full octaves, and contains lots of subtle acoustical stuff – like Phill Niblock’s and Eliane Radigue’s music, it would never survive MP3-ization.

In response to my last post, John offers:

Last year I revisited Emerson’s expansive essay “Nature”. As always, I was amazed at the breadth and depth of Emerson’s mind. And I realized how much I’d missed in my earlier readings. Soon after, I rediscovered Thoreau’s final essay “Walking”. Reading it took my breath away, like listening to the music of the hermit thrush. It felt to me like coming home.

As you say, Emerson and Thoreau couldn’t be closer in spirit. Yet their sensibilities couldn’t be more different….

In my own music, the human presence isn’t represented in the music itself. It’s there in the presence of the solitary listener immersed within the music.

After years composing music inspired by landscape, my recent works – particularly the installations – have literally become places. Now, I’m beginning to invite the human presence of performing musicians to traverse those lonely landscapes. Still, creating place in sound, time and space remains the heart of my work. I feel this is the best gift I can offer to my fellow human animals.

As our species begins to stare our own possible self-induced extinction squarely in the face, I believe that music can serve as a sounding model for human consciousness. Music can help us remember how to listen, and how to know our place within the larger world we inhabit.

All very true. As for me… well, at least I drive a Prius.

AMSTERDAM – The painter Philip Guston was Morton Feldman’s best friend. In 1970, Guston abandoned the abstract expressionist style he had been closely associated with, and began painting cartoonish figures that often included shoes, disembodied eyeballs, and hooded figures. To say Feldman was shocked would be an understatement. As someone recently told me the story (heard from someone else who was there), Feldman came to the initial exhibition and Guston came up to ask him what he thought. For several minutes, Feldman simply couldn’t speak, and Guston slowly and sadly got the point. Finally Feldman just turned away and left, and the two parted ways for years. And Feldman wasn’t the only one. “It was as though I had left the church,” Guston later recalled; “I was excommunicated for awhile.” The dependably venomous Hilton Kramer titled his review of the show, “A Mandarin Pretending to be a Stumblebum.”

Guston: The Street

I have a couple of upcoming performances in Amsterdam, and I got here early to see John Luther Adams and to hear his beautiful sound installations Vespers and Veils. John and I have fantastic conversations. Something about the interaction of his profundity and vagueness and my superficiality and sharpness gives off sparks that seem to intermittently illuminate all of existence. Perhaps the most mind-blowing musical conversation I’ve had in my life was one John and I had about a year and a half ago, walking through the snow and cold outside Fairbanks. I keep meaning to blog about it someday, but I’m still trying to process it. I’ll tell you about it when I can do it justice.

John, as everyone knows, is a composer whose paradigm is nature. Vespers and Veils, based on prime-numbered harmonics of the overtone series, are softly roaring continua. All of John’s works, by his own frequent admission, have to do with the incredible Alaskan landscape he lives within. His pieces are walls of sound: not impenetrable, but gorgeous, relentless, ebbing and flowing, swelling and dispersing, piling up in waves that stretch beyond one’s concert-hall attention span. Veils engulfs you and makes you just want to sit down and be quiet. His orchestra piece For Lou Harrison, just released this month on New World, is a series of avalanches, each one quite like the last but different in detail, before whose massive beauty one can only submit. His music is big, beyond human in its scope, and as impersonal as it is translucent.

Back in the ’80s, I tried to be the kind of composer John is. It was in the air. Cage had unleashed the force of nature into music, and everyone was obsessed with sonority and process, trying to get their own personality out of the music and let nature speak for itself. The objectivity of 12-tone music had given way to a perhaps even greater objectivity of process-oriented logic. But over years of experimentation, I found that nature didn’t speak through me. The natural processes I came up with were more tedious than compelling. I loved Cage’s music, and La Monte Young’s, and Steve Reich’s, and John’s, but it was not mine to write. Whatever joy I took in composing had to do with the personal and subjective: the quirky melodic decoration, the unexpected key change, the rhythmic figure that seems bizarre at first, but finally becomes familiar through repetition. I greatly admired the composers of nature, and wrote about them enthusiastically, but I was not one of them. My muse led in a different direction.

I’d been thinking about this difference between me and John lately, and in discussing it, we wandered into Feldman and Guston. Both of us largely base our music in a Feldmanesque paradigm, an ongoing continuum of only subtle dynamic change. For me, Feldman was not a composer of nature, though he is ambiguous in this respect, and the question is one about which reasonable people could disagree. “Those 88 notes are my Walden,” he said, referring to the piano keyboard, and I interpret that to mean he saw himself not as a channel for nature, but as the Thoreau-like individual reacting to nature. I hear the anxious melodic figures in Rothko Chapel as psychological, not natural, conscious of their alienation and attempting to find release or resolution or integration. Take the incredible passage near the end of Feldman’s For Philip Guston where the music strips down to just four chromatic pitches for a full 25 minutes, and then suddenly opens up into a pure C-major scale across the entire piano: that’s no natural process, the result of no inevitable logic, but an incredible psychic release after almost unendurable repression. Of course, I’m cherry-picking my examples to make the point.

What was revealing was the differing reactions John and I had to Guston’s heretical pictorial style. When he first encountered it years ago, John, he said, had the same reaction as Feldman: he couldn’t believe that a great abstract expressionist had turned away from the wonders of pure color and shape to paint naive-looking figures with strangely personal, idiosyncratic associations. It took him awhile to decide that Guston’s late works were no less masterful than the early ones. I first knew Guston from his earlier work as well, but the shoes and giant eyeballs and hooded figures flooded me with an instantaneous sense of relief. It was liberating. I had been a Jackson Pollock fanatic, or thought I was, but Guston made me realize that I was hungry for art to reintegrate the human element, the personal element, the whimsical and idiosyncratic. Nature is a paradigm that an artist can hardly help worshipping, but ultimately I felt that we also need an art that is about being human, with all the attendant neuroses, embarrassments, longings, and humor. I love(d) abstract expressionism, but I wanted to know how, once we had made our way through it, we were going to come back to dealing with the uncomfortableness and absurdity of human consciousness.

It helped that Guston’s paintings were cartoon-like. I love cartoons myself, and in the ’90s found myself drawn to what I think of as my cartoon music, the stylized appropriations of musical clichés. I especially let myself go in my Disklavier pieces: the rhythmically dislocated ragtime of Texarkana, the deadpan tango rhythm of Tango da Chiesa. I flatter myself that, like Haydn, Ives, and Satie, I am one of the rare composers capable of purely musical humor, independent of extramusical references. My entirely representational Custer and Sitting Bull, with its trumpet calls, Indian flutes and drums, and “Garry Owen” quotations, taps into obvious prototypes. There are deliberate caricatures in my music, skewed pictures and appropriations of familiar musical phenomena.

I fear that, to the sophisticated new-music fans who’ve learned to love the sublime blankness of John’s self-evident canvases, those caricatures must seem like a naive back-pedaling. I often use secondary dominants, and even in these days of returned diatonic tonality, such familiar chords are not “signifiers” of originality. Composers (though never John) sometimes react to my music with the same disappointment that Feldman showed Guston’s late work, denigrating it as merely pastiche or satire, and I’ve learned very well how it feels to seem like a mandarin pretending to be a stumblebum. On the other hand, I think my music may be more comfortable for fans of 19th-century classical music than John’s, in whose wide canvases they might miss a certain expected level of surface detail. In 1989 John Rockwell, kinder than Kramer, called my music “naively pictorial,” and it was a phrase from heaven. I’ve carried the banner of “naive pictorialism” ever since.

I wrote a piano concerto about hurricane Katrina – only it skips over the hurricane. The first movement, “Before,” is an expression of happy thoughtlessness; the second movement, “After,” is about anger, mourning, betrayal, recovery, and includes a stylized image of a New Orleans funeral. If John had written a Katrina piece, it would be about the hurricane. It would be a hurricane.

The “natural” path was not easy to abandon. “New music,” as we called it back then, was almost definable as music that “let nature take its course.” Back in the day I even gave a New Music America lecture titled “The De-Spiritualization of Sound,” about how new music was now about sound waves and not personality, but I gave it with an uneasy conscience. Distinctions like natural versus psychological, literal versus metaphorical, are not trivial: they are the axes in reference to which we position ourselves to stake out aesthetic territory and explore what music means and what it can accomplish, because, thankfully, we’ll never know everything music can achieve. But just as it was fundamentally stupid to think, as so many did in the ’50s, “OK, the age of tonal music is over, from now on music can only be atonal and anyone who lapses back into tonality is not with the times,” it would be equally stupid to think that “history now demands” that music now be always literal in its depiction, or that psychological metaphor must be abandoned as old-fashioned. George Rochberg was right: the problem with 12-tone music was not what it added to our vocabulary but what it tried to subtract, that it attempted to outlaw anything associated with the past. The history of creative music never goes backward, but neither does it ever decide that one side of a creative duality is now useless, and only the opposite side can be gainfully explored.

What’s most fascinating for me, though, is that, if you made an aesthetic map of the new-music world, John would be nearly my closest neighbor. It is immodest of me to link myself with him, I know, because he is far better known as a composer than I am. But as he and I discuss it, we both share a backyard boundary with Peter Garland, with Jim Fox and Mikel Rouse next door, Michael Gordon down the road one way, Larry Polansky the other way, and like that. You couldn’t find two composers more in the same “camp” than me and John. We have the same influences, similar histories, the same heros, the same dreams. But our brains are wired differently, and all those new-music impulses that hit his brain and turn into vast celebrations of nature hit mine and turn into quirky celebrations of personality. He once called me a “force of nature,” but that was a generous projection: he’s the force of nature, I’m a force of culture. (Quite parallel, John still models himself after Thoreau, while I long ago realized I actually prefer Emerson.) It’s astonishing how diametrically opposite people with so much affinity for each other can be when you look at them close enough.

Rumor had it that Pierre Boulez performed in Amsterdam at the same time as the Output Festival, and I think I ran across his group:

Isn’t this the Ensemble InterContemporain, with Pierre on the far right playing drum? In any case, they were the hottest music I’ve heard here so far. There was a lot of I, flat VII, flat VI, V over and over in the bass, but for variety they’d go into I, V, I, ii, V, and there were so many repetitions that I can’t imagine how they kept everything straight at the riotous tempo they took. I was most impressed with the clarinetist in the blue jacket: he’d keep a lit cigarette between his fingers while playing, and puff on it between solos. Fast, fast, fast music, loud and relentless, yet melodically elegant. I had never before thought about writing something for two clarinets, two accordions, sax, and drum, but I’m sure as hell thinking about it now.

…is fantastic, isn’t it? I don’t think there’s been any part of this trip I’ve looked forward to more than just hiding away in some cubbyhole where no one knows how to reach me, and composing my pointy little head off. The phone doesn’t ring, no one stops by, people start to assume you’re unreachable, there’s no refrigerator full of tempting food, there’s not even anything on the walls worth looking at, and if you’re in a country where you don’t speak the language, even the idea of trying to run out and do errands is pretty disinviting. It’s like sensory deprivation, only comfortable. Even back home, I’ve often threatened to go check into a hotel so I can get some work done. And I’m not in a hotel but a short-term apartment, which is even better. There’s no front desk, no maid trying to come in. I have a little kitchen, and a considerable economic incentive to avoid expensive restaurants and eat at home. My only connection to the outside world is this internet cable, and if you need a favor from me, uh, oh yeah, sorry, the blasted internet doesn’t work well here, I didn’t get your message. You’ll never find my phone number here, never. And if I may bring up Kierkegaard again, the Dane had a motto I have always admired: Bene vixit qui bene latuit – “He has lived well who has remained well hidden.”

AMSTERDAM – The new Muziekgebouw hall on the Amsterdam waterfront, which only opened about a year ago, is a spectacular space – or rather, spectacular collection of spaces. In addition to the comfortable and precision-engineered main hall, there is the upstairs black box called Bimhuis (billed as a space for jazz and improv, but actually perfectly well-suited for new music in general), as well as several vast foyers superb for concerts, sound installations, and the like. I’m halfway attending the Output festival of new music employing electric guitars, but mainly hanging out with John Luther Adams, two of whose installations are involved in the festival. Guitarist extraordinaire Fred Frith improvised along with John’s Veils last night, and I’ve also been hanging out with Renske Vrolijk, Anthony Fiumara, Tim Brady, Derek Bermel, and the ubiquitous Samuel Vriezen:

The Muziekgebouw is also where the Orkest de Volharding will perform my piano concerto October 31. It appears to be where almost all Amsterdam new-music activity takes place these days.

Today I’m giving a lecture on Nancarrow’s late player piano studies at the Royal Conservatory in Aarhus, courtesy of expatriate American composer Wayne Siegel, whose music I’ve been following for more than a couple of decades now. I suppose it’s not an event open to the public, but I’m not sure.

One that is open, though, will be a performance at the Weis Center at Bucknell University in Lewisburg, PA, this Friday night at 8. Lois Svard, assisted by pianists Megan Rowland and Anja Wade, will play my Long Night for three pianos. Although Sarah Cahill’s recording came out a couple of years ago, the piece hasn’t been performed publicly since New Music America 1982 – which, coincidentally, was the festival Wayne Siegel and I were both on. Lois is also playing solo works by two of my best friends, William Duckworth and George Tsontakis. I call the concert “Kyle Gann and His World.” They don’t.

I, however, will be in Amsterdam by that point. And my next performance is October 9 at the Karnatic Lab there. I’ll give you details later.

And one more, Nytorv Square, where Kierkegaard grew up:

It’s not only about Kierkegaard, but about the regret of being a historian from a young country, and wanting to make the 1840s come alive.

The house in which Kierkegaard grew up, and which he later owned (buying out his brother’s share), was on a site where the Danish Bank now sits, though there’s a plaque making the spot:

I had lunch at a diner, across the square, that was built around 1830. Prostitutes used to frequent it, and you can’t tell me Søren never went in there. His final address was 38 Skindergade:

Vor Frue Kirke, Our Lady’s Church, is so large, and the neighborhood around it so crowded, that it’s difficult to get far enough back for a decent photo. But I went to a service there Sunday night, where the soprano and organ both performed in the most meltingly pristine timbres:

Finally, Monday afternoon, I caught up with the guy I’d been looking for. Turned out I was 151 years too late, but we still enjoyed a cigar together (only vicariously on his part):

All around him are burgomeisters and local dignitaries with big monuments graced by busts in relief – but Kierkegaard, appropriately parallel to Thoreau, is just one unaccented figure in a family grave. The tombstone, according to a site I found on the internet, is a verse from an 18th-century hymn by Hans Adolph Brorson, translating as follows:

There is a little time,

Then have I won,

Then will the entire strife

Be suddenly gone,

Then can I rest

In halls of roses

And ceaselessly [with]

My Jesus speak.

I won’t show you Hans Christian Andersen’s grave, or the statue of The Little Mermaid, because you’ve seen it and I wasn’t very impressed. But lastly, for Alex Ross, here’s the site of another inextinguishable Dane:

You can’t believe everything you read in music reference works, but I verified this one personally: he’s dead.

I had an idea of blogging an ongoing photo essay under the rubric “Unattractive Danish Women,” but I couldn’t get any material. I think I could have replaced it, though, with one on “Tormented-Looking Young Danish Men.” Ever since Kierkegaard, walking through town with visible signs of being haunted by existential angst seems to have become a national patrimony. Or maybe they’re just all trying to become the next existentialist hero.

As I write this, I am finally on the plane to Copenhagen. By “finally,” I mean after 30-something years. I’ve always known Copenhagen would draw me to it someday. It was unthinkable that, in my lifetime, I would fail to walk the streets that Søren Kierkegaard spent his life walking up and down. It is difficult to think of a writer more specifically tied to his location than Kierkegaard – the neighborhood surrounding the Vor Frue Kirke (Church of Our Lady) in which he inveighed against the local clergy by name often appears in his writings as an explicit background, and, as the most prominent writer in a language little spoken around the world, he was acutely conscious of not only being a Danish author but a Copenhagen author, speaking to a Copenhagen public with reference to Copenhagen geography. Every year I make a pilgrimage to Concord, Massachusetts, to retrace the steps of Thoreau, Emerson, and even lesser-known Transcendentalists – Jones Very and Orestes Brownson, anyone? – and doing the same for Kierkegaard is a pleasure, a mandate, too long delayed. I suppose I have a rather peculiar need to soak up the native ambience of writers who have been central to my life.

How the theologically provocative author of Fear and Trembling became one of those writers is difficult to say. I was reading Sartre in college, without understanding him much, because existentialism seemed like the cool philosophical trend of the time. Camus had a more concrete impact. I remember thinking that The Myth of Sisyphus did more than even ale could to “justify God’s ways to man.” But working backward through existentialist chronology, I ran into Heidegger, Husserl, Nietzsche, and finally Kierkegaard, and while I would later explore the others, it was only this last who grabbed deeply into my imagination. Perhaps I was attracted by the glancing resemblance of his last name to my full name, or the coincidence that he died almost exactly a century before I was born. More likely his position as the first phenomenologist of anxiety, fear, and depression offered a promise of kinship to my adolescent introversion. Whatever the underlying psychology, I spent, at Oberlin, a depressive, reclusive year reading almost half of the 43 books Kierkegaard wrote in his feverish 17 years of authorial activity, ignoring all else. The next year, once that fetish had played out, I sank even further into the abyss and read nothing but Samuel Beckett, who at least had the advantage of being considerably more concise. The less said about that spiritual crisis, the better. Suffice it to say that Godot did not arrive.

How the theologically provocative author of Fear and Trembling became one of those writers is difficult to say. I was reading Sartre in college, without understanding him much, because existentialism seemed like the cool philosophical trend of the time. Camus had a more concrete impact. I remember thinking that The Myth of Sisyphus did more than even ale could to “justify God’s ways to man.” But working backward through existentialist chronology, I ran into Heidegger, Husserl, Nietzsche, and finally Kierkegaard, and while I would later explore the others, it was only this last who grabbed deeply into my imagination. Perhaps I was attracted by the glancing resemblance of his last name to my full name, or the coincidence that he died almost exactly a century before I was born. More likely his position as the first phenomenologist of anxiety, fear, and depression offered a promise of kinship to my adolescent introversion. Whatever the underlying psychology, I spent, at Oberlin, a depressive, reclusive year reading almost half of the 43 books Kierkegaard wrote in his feverish 17 years of authorial activity, ignoring all else. The next year, once that fetish had played out, I sank even further into the abyss and read nothing but Samuel Beckett, who at least had the advantage of being considerably more concise. The less said about that spiritual crisis, the better. Suffice it to say that Godot did not arrive.

I had been raised in the Southern Baptist Church, steeped in a representation of religion that, of course, no intellectually responsible person could permanently stomach. Its most ludicrous excess was something I once attended, at 15, called the Bill Gothard Seminar, in which the eponymous charismatic worthy tried to impress on a stadium-sized congregation that the exhortations of the New Testament were good business principles; that if we followed the Christian life we would become successful in society; and that, ergo, you could tell who the best Christians were because God rewarded them with the most money. Against this repellent positivistic caricature, still quite common among the Religious Right to this day, Kierkegaard’s antipodal insistance on spirituality as a completely individual matter, and one whose rigorous fulfillment was bound to rather set a person off from society than endear him to it, seemed, to say the least, infinitely more authentic.

Of course, I was a musician too, and while the “Or” of Either/Or held a certain academic interest, it was the “Either” that I devoured with page-flipping relish. Kierkegaard’s pseudonymous division of his authorship into “aesthetic” versus “ethical” or religious personas may have been ironic in intent, with a finger on the religious side of the scale, but his detailed psychology of the total aesthete was, as he knew, the more seductive. His argument about Don Giovanni – that since the seducer is the personality most trapped in time, and music is the art that deals with time, seduction is the perfect musical subject, therefore Don Giovanni is the most perfect possible piece of music – wasn’t very convincing then or now, despite the persuasive fanaticism with which it is developed. But he captured and conveyed, in startlingly vivid terms, the manic subjectivism of a mental life turned away from the quotidian world and devoted to the absolute in art. To read that was a heady loss of innocence, a recognition that someone else had heard the same siren song I did – and followed it.

Ultimately, I think perhaps I found in Kierkegaard a model for the pose that takes inwardness as an absolute, defying all collective social claims. He knew that getting a degree in theology does not make one a Christian; that preaching does not make one a Christian; that going about ostentatiously helping those in need does not make one a Christian; that honors bestowed upon one by the church do not make one a Christian; that ultimately, one only becomes spiritual, becomes a Christian, by a radical adherence to one’s inner voice, more likely to manifest by becoming an eccentric or even martyr than by becoming a famous preacher. To transpose the effect of this absolute to the artistic sphere is hardly difficult. One does not become an artist by getting graduate degrees in composition, by attaching oneself to famous teachers, by learning how to orchestrate proficiently, by winning prizes and commissions, by being championed by one’s conductor friends, by getting hired to teach in prestigious music departments. One might very well become a “famous composer” by doing all those things, and many have. But one becomes an artist by discovering a universe inside, by having something to say and saying it, no matter how bizarrely that “it” contrasts with the musical context of one’s contemporaries. Kierkegaard defended spirituality from the established church of his day, and taught me how to defend musical creativity from the established musical world of mine.

For instance: “Take away the paradox from a thinker,” Kierkegaard wrote in his journals, “and you have – a professor.” This thought brings to my mind the story about the visit Morton Feldman made to Northwestern when I was a grad student there, which I’ve related many times. Feldman spoke about how impossible it was to teach composition in a university, and one angry student asked, “How can you spend your life doing something you don’t believe in?” Feldman’s quizzical reply was: “That’s the definition of matyoority.” Mystic that he was, he could have couched his answer in more Kierkegaardian terms, that to keep alive the paradox in music is to teach composition knowing that composition can’t be taught. Feldman, living the paradox and never yielding to the temptation of pedagogical certainty, was no mere professor. The gradually crescendoing influence of his music from the ground up, students first, in the 1980s and ’90s was a triumph of radical subjectivity, and likewise a dramatic refutation of what one could call the Bill Gothardism of new music: the facile, bullshit assumption that you can tell who the great composers are, because they’re the ones getting the orchestra commissions and Pulitzer Prizes.

Immersion in Kierkegaard was a great preparation for one who feels called upon to live a life telling the social institutions of his day: “You are wrong, you are beyond wrong, you are premeditatedly mendacious for self-serving reasons.” Note that this is not identical with the potentially delusional claim, “I am right and the rest of the world is wrong.” After all, Kierkegaard became famous in his 20s because his criticism of official religion found quite a bit of resonance among his and the younger generation. But he does bring us close to that wonderful quote from Thoreau: “Any man more right than his neighbors constitutes a majority of one.” Kierkegaard created the template, as it were, for the irrefutable defense of subjectivity against the awesome, socially reified power of institutions with their rafts of university-certified experts. Just as the spiritual man is the spat-upon martyr, not the famous preacher, the artist is not an orchestra jockey with a long list of prizes and residencies on his web site, but someone completely uncertifiable and vulnerable – because his only possible claim on our attention is the innate persuasiveness of his musical vision. In the absolute world of art, as in the absolute world of religion, subjective inwardness reigns supreme. College degrees, prizes, institutional positions, worldly honors, laudatory reviews, objective certifications of any kind mean nothing and less than nothing. Kierkegaard made it easier to say that.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Today, I admit, I can’t really read Kierkegaard anymore. His energy, once so tempestuously absorbing to a kindred soul, now often seems overly neurotic. His religious concerns are not mine: indeed many think that by proving Christianity virtually absent from the Christian church, he instead proved Christianity impossible. His dialectical anti-Hegelian critique, so subtle in its circuitous machinations, is of interest only to historians of philosophy. (Though in his championing of subjectivity against all philosophical systems, he does provide yet another parallel to the implied Feldmanesque critique of mid-20th century musical ideologies.) To prepare for Copenhagen, I read instead the massive, fairly new biography by Joakim Garff, which is as absolutely complete as one can imagine, not only sifting through the entire documentary evidence of Kierkegaard’s life, but providing helpful summations of most of his works, giving extensive background on Copenhagen and the otherwise long-forgotten characters in Kierkegaard’s circle, and also treating its eccentric subject with a healthy blend of admiration and absurdist humor. (At the end of one book, Kierkegaard admits sheepishly that he is not the martyr Christianity is waiting for, merely a genius – and Garff comments, “Kierkegaard had an interesting way of showing modesty.”) The biography brought S.K. alive again for me, not from the inside this time, but felicitously from the outside. What a fantastic tome.

One of my oldest friends, reading me in the Village Voice, once accused my style of being a cross between Mark Twain and Theodor Adorno. There was some truth to it, but there is a wide underlying swath of Kierkegaard as well. When I fall into some of my more repetitively manic moments, I think I channel him a little bit. In addition, I fancy that I’ve managed to live my life with a certain Kierkegaardian irony. I got a doctorate not because I though I would gain anything from so doing, but because I wanted to be able to attest to the worthlessness of the credential. I had observed that academia is impervious to shots fired from outside the walls, so I made it my plan to shoot them from inside. It’s true that I obtained an academic position, but under slightly false pretenses: as a music historian, not as a composer. And now I live, Kierkegaardianly enough, as the paradoxical “composer who is not a composer,” taking aim at the artistic stupidity and certification-worship of musical academia, leaving myself neither acceptable in the circles I inhabit nor quite completely dismissible. Without meaning to aggrandize my importance, I think I can say I’m a little parallel, on a smaller scale, to this “preacher who was not a preacher,” this Danish theologian who was fully qualified to preach in church, who took high honors in university and was in fact famous for his published sermons – but who was neither ever granted a pastorship nor entirely willing to take one.

And today, with cigar similarly clenched in teeth, I’m going to follow his footsteps from the Vor Frue Kirke, where his controversial funeral nearly caused a riot, across the bridge to Christianshavn, from whence he liked to look back at his native city – while thanking him for steeling me for the rough road of the paradoxical, radically subjective life.

My mom got her master’s in music ed when I was a kid. Afterward I inherited (in the same sense that my son “inherits” books and CDs from me now – Mom’s still around) her heavily underlined copies of Joseph Machlis’s Introduction to Contemporary Music and Baker’s Biographical Dictionary of Music and Musicians, the books from which I first learned about new music. When I was 12, already heavily into classical music, I asked Mom one day why there were no American composers. She said she thought there were, and gave me two names: Charles Ives and Roy Harris. I sprinted out and bought John Kirkpatrick’s recording of Ives’s Concord Sonata, which somehow looked to be his most celebrated work – perhaps Machlis had said as much. Once home, I had no idea what to think of it. It seemed a towering mess. I had already partly digested The Rite of Spring, which was bizarre enough, but at least its comparative repetitiveness made its oddities stick in my head. The Concord Sonata was just a mass of notes with, here and there, a tune, even a quotation I recognized. But I listened over and over and over, struggling to make sense of it. And gradually, inevitably, I fell absolutely in love. It became my favorite piece of music, and remains so to this day.

In retrospect, it’s odd that that piece should have become so central to my life. As devoted as I am to every note Ives wrote, he and I are not similar creative types. He was an early bloomer; my style, despite my precocious interests, didn’t really coalesce until I was 38. His pieces are omnivorous; mine rather finely focused. He was the most wildly intuitive and improvisatory of composers; I delight in the minute logic of voice-leading within well-defined postminimalist limits. (Satie, my other great love, is a more congenial model.) Still, Ives and I do have in common, or perhaps I picked up from him, that we both like to start with tonality and then muck it up. Certain Ivesian effects in my music have been pointed out to me; the ostinato-based, diminuendoing final section of my Desert Sonata is an homage to the endings of both of Ives’s sonatas, and in the first movement of Custer and Sitting Bull I build up Custer’s tune “Garry Owen” in much the same gradual way Ives, in his second symphony, builds up “Columbia the Gem of the Ocean.” Much of my creative life has suggested a child trying alternately to imitate, and to separate from, a father he very little resembles.

All along the Concord has remained the piece I’m most obsessed with. I own three copies of the score; one (delapidated and heavily marked) for home, one for the office, and a small Kalmus copy for travel. In college I learned to play the last two movements quite well; I’ve never worked up even the first page of “Emerson,” while the pianism that “Hawthorne” requires is beyond my kinetic imagination. Still, a like-minded composer friend and I once agreed that if someone got a note wrong in the middle of one of those big tone clusters, we’d hear it, because everything in that piece is so calculatedly transparent. I could write a panegyric to the Concord as effusive as Kierkegaard’s over-the-top essay on Don Giovanni in Either/Or, similarly demanding that everyone in the world acknowledge it as the one perfect composition.

All this prologue is to set up how excited I was to receive in the mail this weekend the Innova recording of the Concord Sonata – orchestrated by Henry Brant. In addition to being the leading composer for spatially separated ensembles, Brant has always had a reputation (furthered by Virgil Thomson’s writings from way back) as one of the greatest orchestrators ever. I heard his orchestration of the Concord, quite aptly retitled A Concord Symphony, at its New York premiere back in 1996, and was blown away then. This live recording by Dennis Russell Davies and Holland’s Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra makes it even more exquisite.

All this prologue is to set up how excited I was to receive in the mail this weekend the Innova recording of the Concord Sonata – orchestrated by Henry Brant. In addition to being the leading composer for spatially separated ensembles, Brant has always had a reputation (furthered by Virgil Thomson’s writings from way back) as one of the greatest orchestrators ever. I heard his orchestration of the Concord, quite aptly retitled A Concord Symphony, at its New York premiere back in 1996, and was blown away then. This live recording by Dennis Russell Davies and Holland’s Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra makes it even more exquisite.

To imagine, in one’s head, the Concord orchestrated evokes chaos: how could that mammoth opening page be transferred to 80 musicians and still remain coherent at all? But Brant does it, lovingly bringing out every line with a clarity achievable only by someone who worships the piece. One doesn’t exactly think of the Concord as a polyphonic work, but Brant finds its polyphony and accentuates it. Despite the complexity, grandeur, and mass dissonances, the lightness of his scoring, its almost chamber character, is the dominant impression. Many, many passages are handed to instruments I would never have thought of. The tranquil melody in the middle of “Alcotts” is played by a trumpet – perfectly so, thus tieing into a 19th-century parlor use of the instrument that died out in the 20th. The harmonic series arpeggios in the long prose section of the middle of “Emerson” first appear in the harp, logically enough, and then in the cellos, somehow managing to retain the feeling of piano pedalling. The ultrapianistic opening of “Hawthorne” flits mercurially between winds and percussion, changing some of the arpeggios into impressionistic chords.

Indeed, the character of the piece is somewhat changed; the climax of “Alcotts,” for instance, set in the brass, is rather toned down from the original, because trying to play the entire piano at once and playing the entire orchestra at once do not have the same effect; what sounds like incredible yearning on the piano would turn to facile bombast in the orchestra, which Brant tastefully avoids. This is not merely a Concord transferred to orchestra, and Brant was wise to give it a separate name. There are passages I might not necessarily have recognized, so changed is the music’s texture – but the spirit is devoutly maintained. It’s a new work, a new Ives symphony, with far more chamber-like orchestration than his other symphonies, as was necessary to bring the pianistic content across. It is unheard before, and yet strangely familiar. It is faithful to the original with a devotion and intelligence that go beyond mere transcription. I look forward to falling in love with it all over again.

I write for nonexistent orchestras, peopled by superhumans. I need pitches and harmonies beyond the scope of current acoustic instruments, fingered in rhythms no musician can count. And so, despite a dearth of training in the field, despite a lack of talent for the technology, I am driven to make electronic music that will not be considered electronic music by electronic composers. My music argues its way into a no-man’s land in which even the simple category of medium is denied it: it exists entirely as a digital soundfile, but it is, by universal consensus, not electronic music. There is no side-stepping this dilemma – but I have finally found a solution for it. I can’t produce my music alone, but I can collaborate with people who have finer control over the technology than I do. I can supply the pitches and rhythms – the meaning, the content – and leave the coloring, the timbre, to someone else.

And so Mike Maguire and I have completely remade my one-man music theater piece Custer and Sitting Bull. Mike (whose composing name is M.C. Maguire) is not only one of the most surprising and innovative composers around, but an expert commercial sound engineer with broad experience in commercials and film. So I gave him the MIDI files and some general pointers, and he’s completely refitted the piece with new sounds, from the ground up – we got together in Toronto to go over the results with a fine-tooth comb. Mike’s sounds are indeed grittier, livelier, more energetic than the ones Dale Hourlland and I had once coaxed out of 1999 technology, but – what’s most important to me – they feel as supple and definite to perform with. I hope this stills some of the complaints I get about my electronic timbres, and if not, that’s the end of the line – my music is not for everyone. It’s my observation that some people are so attuned by pop music that they can listen only to production, to the extent that distinctions of syntax escape them if unorthodox production values get in the way. And then, to people reluctant to bend their ears to it, microtonal music will always sound simply out-of-tune, and the strangeness gets projected onto other elements as well.

And so Mike Maguire and I have completely remade my one-man music theater piece Custer and Sitting Bull. Mike (whose composing name is M.C. Maguire) is not only one of the most surprising and innovative composers around, but an expert commercial sound engineer with broad experience in commercials and film. So I gave him the MIDI files and some general pointers, and he’s completely refitted the piece with new sounds, from the ground up – we got together in Toronto to go over the results with a fine-tooth comb. Mike’s sounds are indeed grittier, livelier, more energetic than the ones Dale Hourlland and I had once coaxed out of 1999 technology, but – what’s most important to me – they feel as supple and definite to perform with. I hope this stills some of the complaints I get about my electronic timbres, and if not, that’s the end of the line – my music is not for everyone. It’s my observation that some people are so attuned by pop music that they can listen only to production, to the extent that distinctions of syntax escape them if unorthodox production values get in the way. And then, to people reluctant to bend their ears to it, microtonal music will always sound simply out-of-tune, and the strangeness gets projected onto other elements as well.

This is no apology, for none is needed. Mike did a fantastic and creative job, amplifying effects beyond my ability to conceive of electronically, and even making suggestions that tightened up the syntax. I wish I could hire him for many more such projects, but he’s got his own unutterably complex music to write. Here are the new versions for you to give a listen to:

Custer: “If I Were an Indian…” (8:42)

Sitting Bull: “Do You Know Who I Am?” (8:17)

Sun Dance / Battle of the Greasy-Grass River (7:59)

Custer’s Ghost to Sitting Bull (10:04)

And if you want, you can compare them to the old ones (originally issued on Monroe Street), below. I’d be curious how much change people think there is:

Custer: “If I Were an Indian…” (8:42)

Sitting Bull: “Do You Know Who I Am?” (8:17)

Sun Dance / Battle of the Greasy-Grass River (7:59)

Custer’s Ghost to Sitting Bull (10:04)

Also, the Monroe Street version was recorded before I had performed the piece live. After some three dozen or so performances, I think I intone the text much better in the new version. Program notes and texts are here, and recently, without mentioning it, I uploaded as a PDF the entire 322-page MIDI score, which you can find here – though it’s 146 MB in size, and a hell of a long download. (You can still get a bound hard-copy score from Frog Peak for only $20, and it’ll be a lot more convenient.) Though I wrote it between 1995 and ’99, I still consider it my most ambitious and successful piece, at least in terms of integrating the harmonic and rhythmic sides of my musical language. I’ll be giving the world premiere of this new version October 9 in Amsterdam, at the Karnatic Lab.

I tend to buy more scores in the UK than CDs. The kinds of British composers who get their recordings into the stores are, as here only more so, not really the postclassical variety. I don’t listen to the recordings I already have by Harrison Birtwhistle, Thomas Adès, James Dillon, Peter Maxwell Davies, and so on, avidly enough to justify busting my frail bank account of puny little Americo-dollars trying to get every recording I’d never seen before by them all. I do, however – and it is always my first act in London – run through the entire piano music collection at Foyles, followed in short order by the orchestral and chamber scores. Then I head for Travis & Emery at Circle Court and see what they’ve got in. This trip, in addition to purchases already mentioned, I landed Feldman’s Coptic Light, Messiaen’s Vingt Regards, Pärt’s Fratres, and quite a bit of piano music by Howard Skempton, Michael Parsons, and Christopher Hobbs. (Did I ever tell you about the critic down south who decided to translate the title of Vingt Regards sur l’Enfant Jésus and came up with, “Give My Regards to the Infant Jesus”? True story. “And remember me to the Holy Ghost,” I guess.)

But you knew I’d come back from a minimalism conference with some new obscuuuuuuuure recordings for Postclassic Radio, and I haven’t disappointed you. You’ll hear plenty of CDs that give me that “Titles not found in CDDB database” message when I load them into iTunes. Christopher Hobbs, as I mentioned, was at Wales. I called him one of the original British minimalists, but I note now that he was born only in 1950. From the fact that Michael Nyman was writing about his music in 1974, I had him pegged for much older – that would have been like someone writing about my music in 1979, which no one was. But Hobbs’s Sudoku pieces, based on the newspaper puzzle (never worked one myself), are exotically listenable and remarkably varied, and after hearing them here you can get them at Experimental Music Catalogue.

But you knew I’d come back from a minimalism conference with some new obscuuuuuuuure recordings for Postclassic Radio, and I haven’t disappointed you. You’ll hear plenty of CDs that give me that “Titles not found in CDDB database” message when I load them into iTunes. Christopher Hobbs, as I mentioned, was at Wales. I called him one of the original British minimalists, but I note now that he was born only in 1950. From the fact that Michael Nyman was writing about his music in 1974, I had him pegged for much older – that would have been like someone writing about my music in 1979, which no one was. But Hobbs’s Sudoku pieces, based on the newspaper puzzle (never worked one myself), are exotically listenable and remarkably varied, and after hearing them here you can get them at Experimental Music Catalogue.

Also going up (and locatable at the same web address) are piano pieces by Hobbs’s colleague Michael Parsons, whose Satie-ish piano works are surprising, quirky, and charming. Hobbs, Parsons, Skempton, and John White are among that generation of truly postclassical British composers of the 1970s whom Nyman’s Experimental Music book teased us with, and then we almost forgot they existed. Turns out they’ve continued to make increasingly beautiful and subtle music without every losing their experimental spirit. Whether there is a younger British generation following in their footsteps, aside from Chris Newman whose work I already knew, I didn’t find out.

And on the subject of Serbian postminimalism, which I’m sure you’ve brought up at a cocktail party by now, I’m happy to present several pieces by my new friend Vladimir Tosic (b. 1949 – his last name needs a couple of diacritical marks that I can’t achieve with this keyboard). Tosic adheres to what he calls “reductionist techniques,” which I guess is how they talk about minimalism in Belgrade, but his music does sound somwhere in-between the studied flatness of American minimalism and the affectless irony of Russian postminimalism. It is often, withal, hauntingly beautiful, and to prove that I’m putting one piece, Voxal for piano and string orchestra, on my web site where you won’t have to search for it. In Serbia, someone whose music melts on the ears as languidly as Harold Budd’s can get access to orchestras, and if you’ve wondered what that would sound like, – click!

And on the subject of Serbian postminimalism, which I’m sure you’ve brought up at a cocktail party by now, I’m happy to present several pieces by my new friend Vladimir Tosic (b. 1949 – his last name needs a couple of diacritical marks that I can’t achieve with this keyboard). Tosic adheres to what he calls “reductionist techniques,” which I guess is how they talk about minimalism in Belgrade, but his music does sound somwhere in-between the studied flatness of American minimalism and the affectless irony of Russian postminimalism. It is often, withal, hauntingly beautiful, and to prove that I’m putting one piece, Voxal for piano and string orchestra, on my web site where you won’t have to search for it. In Serbia, someone whose music melts on the ears as languidly as Harold Budd’s can get access to orchestras, and if you’ve wondered what that would sound like, – click!

Keith Potter informed me that, since my last visit to London, John Buller had died (in 2004, aged 77). Buller had to be one of the most wildly original figures in British music. His Proença of 1977 set a number of troubadour songs with an electric guitar in the orchestra. The Theatre of Memory (1981), based on Renaissance memory techniques, began with the orchestra members all playing chaotically at their own rate, after which the conductor finally walks onstage and brings them together with a resounding downbeat. Startling stuff, with a notational looseness sort of in the Crumb/Kagel/Schwantner realm, but more substantial and engaging, in my opinion, than any of those names. You’ve never heard of him. Like the US, the UK puts its staid, “respectable” composers in the limelight, and hides its crazy endearing geniuses under a bushel. That must be where we inherited it from.