I complained to the singer I’m working with that some of my composer colleagues insist that virtually every note in a score should be marked with a dynamic and articulation marking – something I refuse to do. She replied: “Oh, I hate it when I feel hemmed in by the composer. I want to look at the notes and think, ‘What do I need to do to bring this line to life?'” That’s why I’m working with her. I would be irritated working with a performer who needed to be spoon-fed every phrase-shape, just as I would be bored writing a piece that sounded the same no matter who performed it.

Alternative to Despair

I had a vivid dream this morning that I was working for a music festival, which has happened to me in real life before, and in the course of my administrative work came across a conceptual piece by some early modernist artist (which I seemed to recall having known about before). It was a test tube with a scroll inside it directing one to open the much smaller test tube inside in case of suicidal thoughts. And the smaller test tube contained a tiny scroll of paper reading, “The usage is, instead of committing suicide, to write a canon.†This seemed so familiar to me upon waking that I Googled the phrase (in vain), thinking I must have read it somewhere.

I hasten to add that it has been very many years since I was plagued with what I believe is now called suicidal ideation. I am not depressed, but I am still writing canons. The odd wording instantly brought to mind the Almighty fixing his “canon ‘gainst self-slaughter” in Hamlet, and also the annotation to Satie’s Vexations, at the bass line where it says “À ce signe il sera d’usage de présenter le thème de la Basse.” I don’t possess the insight to tease out what this little constellation of meanings signifies, but now, when a student comes in depressed, I might start saying, “Why don’t you try writing a canon?”

Reflections on Glass

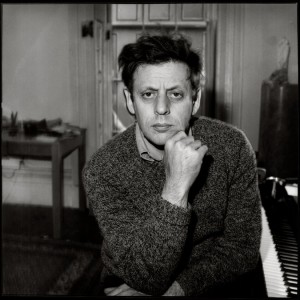

Today marks my first appearance as a writer in the New York Times since 2003. They asked me for a review of Phil Glass’s new memoir Words Without Music.

Today marks my first appearance as a writer in the New York Times since 2003. They asked me for a review of Phil Glass’s new memoir Words Without Music.

Some Early Minimalism Resurfaces

I was unaware of the Entourage Music and Theater Ensemble, which started in Baltimore and operated from 1970 to 1983 – surprisingly unaware, because though those were my college years, I was seeking out Terry Riley, John Cale, Brian Eno, and any shards of information I could find on La Monte Young and Charlemagne Palestine. I was spending hours a week in record stores, and their ambient style was right up my alley. But Wall Matthews, the group’s “last surviving member,” is launching a new web site for this group that was somewhat parallel, in the dance world, to Young’s Theatre of Eternal Music, and so there’s a chance to discover them long after the fact. I’m curious whether they were on the radar of my fellow minimalism aficionados.

I was unaware of the Entourage Music and Theater Ensemble, which started in Baltimore and operated from 1970 to 1983 – surprisingly unaware, because though those were my college years, I was seeking out Terry Riley, John Cale, Brian Eno, and any shards of information I could find on La Monte Young and Charlemagne Palestine. I was spending hours a week in record stores, and their ambient style was right up my alley. But Wall Matthews, the group’s “last surviving member,” is launching a new web site for this group that was somewhat parallel, in the dance world, to Young’s Theatre of Eternal Music, and so there’s a chance to discover them long after the fact. I’m curious whether they were on the radar of my fellow minimalism aficionados.

My Trajectory Leads Back to Provence

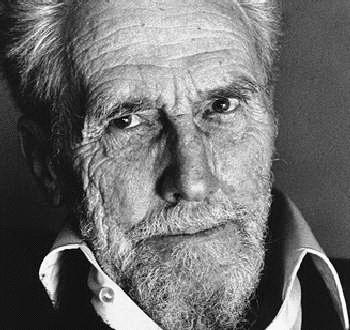

“I knew at fifteen pretty much what I wanted to do… I resolved that at thirty I would know more about poetry than any man living, that I would know the dynamic content from the shell…”

– Ezra Pound, “How I Began” (1913)

A thrill ran up my spine when I read those words in college, for I harbored an identical ambition with respect to music. I recognized a kindred spirit, someone who was not only obsessed with an art form, but for whom creating in that art form was not enough: he had to devour and digest the entire history of the art, the repertoire going back to the dawn of recorded history. The obsession was not with “my art,” but with “all art leading up to mine.” (Pound was not yet thirty when he wrote that.) I became an Ezra Pound fanatic for several years, and the Pound preoccupation intersected with a burgeoning love for medieval music to promote my self-immersion in the troubadours (or, as I prefer to spell them in Provençal rather than French, trobadors). I actually studied Provençal for a semester with a Pound scholar, named Peter Way, who was living in Oberlin, Ohio, at the time but not teaching there. I memorized passages of Pound’s early poems, especially the Provençal-inspired ones; the Cantos I found forbidding. Perhaps the disturbing reputation of Pound’s later decades played some role in Pound’s finally dropping outside my focus. Still, when our medieval literature professor at Bard teaches the troubadours, she brings me in to lecture on the music, and I have a blast doing it.

A thrill ran up my spine when I read those words in college, for I harbored an identical ambition with respect to music. I recognized a kindred spirit, someone who was not only obsessed with an art form, but for whom creating in that art form was not enough: he had to devour and digest the entire history of the art, the repertoire going back to the dawn of recorded history. The obsession was not with “my art,” but with “all art leading up to mine.” (Pound was not yet thirty when he wrote that.) I became an Ezra Pound fanatic for several years, and the Pound preoccupation intersected with a burgeoning love for medieval music to promote my self-immersion in the troubadours (or, as I prefer to spell them in Provençal rather than French, trobadors). I actually studied Provençal for a semester with a Pound scholar, named Peter Way, who was living in Oberlin, Ohio, at the time but not teaching there. I memorized passages of Pound’s early poems, especially the Provençal-inspired ones; the Cantos I found forbidding. Perhaps the disturbing reputation of Pound’s later decades played some role in Pound’s finally dropping outside my focus. Still, when our medieval literature professor at Bard teaches the troubadours, she brings me in to lecture on the music, and I have a blast doing it.

In February I went to Kansas City to lecture on Ives, partially at the invitation of my friend David McIntire. Michelle McIntire, his wife and a singer and voice teacher, expressed a desire to perform some of my music, suggesting I write something for her. Michelle has a wide range but a low tessitura, with an especially nice quality in the octave around middle C. All of my songs for female voice are written in soprano register. I came home, pulled out the usual suspects among my poetry books. Low female voice I associate with sensuality, the sotto voce side of life. The troubadours registered in the back of my mind Рin my youth early-music groups sang them in the style of sacred music, but I always thought their celebrations of illicit sex would have been more at home in smoke-filled jazz clubs. I pulled out my old friend Pound and conceived of his troubadour poem Na Audiart sung with a cool, jazzy accompaniment of flute, vibraphone, electric piano, electric bass. Poem quickly led to poem, and a huge song cycle with the title Proen̤a (the Proven̤al word for Provence) exploded in my head.

So now Proença comprises six songs lasting a projected forty-five minutes (of which I have a half-hour completed), and I’m not sure that will be the end of it. I have two Pound songs based on the warrior-troubadour Bertrans de Born (pictured), Na Audiart and Near Perigord* (excerpted); two Pound translations of troubadour poems, Arnaut Daniels’s “L’aura amara” and the anonymous alba “En un vergier sotz fuella d’albespi” (which Pound called the best alba ever written**); and two settings of 12th-century poems in Provençal, Bernart de Ventadorn’s “Pois preyatz me senhor” (with the original melody), and the Comtessa de Dia’s “Estat ai en greu cossirier,” which I picked in order to have a poem by a woman for which no pre-existing tune had survived. I could so easily go further, there are so many troubadour poems I love and Pound poems, and my poet friend Michael Ives introduced me to the tautly energetic troubadour translations of Black Mountain poet Paul Blackburn (1926-71), which I’d also consider. On the other hand it’s a lot of music to pour into Michelle’s brain, and an odd instrumentation to ask an audience to listen to for half an evening. As it is, she’s thinking about a winter premiere and recording it next summer.

So now Proença comprises six songs lasting a projected forty-five minutes (of which I have a half-hour completed), and I’m not sure that will be the end of it. I have two Pound songs based on the warrior-troubadour Bertrans de Born (pictured), Na Audiart and Near Perigord* (excerpted); two Pound translations of troubadour poems, Arnaut Daniels’s “L’aura amara” and the anonymous alba “En un vergier sotz fuella d’albespi” (which Pound called the best alba ever written**); and two settings of 12th-century poems in Provençal, Bernart de Ventadorn’s “Pois preyatz me senhor” (with the original melody), and the Comtessa de Dia’s “Estat ai en greu cossirier,” which I picked in order to have a poem by a woman for which no pre-existing tune had survived. I could so easily go further, there are so many troubadour poems I love and Pound poems, and my poet friend Michael Ives introduced me to the tautly energetic troubadour translations of Black Mountain poet Paul Blackburn (1926-71), which I’d also consider. On the other hand it’s a lot of music to pour into Michelle’s brain, and an odd instrumentation to ask an audience to listen to for half an evening. As it is, she’s thinking about a winter premiere and recording it next summer.

So I’m not sure how much further to go. I mentioned to a distinguished poet on the faculty that I was writing a song cycle on Pound and she spit out, “That bastard!” I know, but I do not believe in holding the artist’s faults against the art. Who knows but that I may be in the doghouse myself someday? And should my music therefore suffer? Pound’s later fascist sympathies aside (and I’m using only pre-1920 texts), those poems have been lovingly settled into the back of my brain for so many decades. Pound planted the seeds of a troubadour fascination forty years ago, and they only needed a drop of attention to blossom into a tropical forest of inspiration.

*It’s difficult to refer to Near Perigord when you’re very used to talking about the Danish composer Per Norgard.

**An alba is a formulaic medieval poem warning two lovers who shouldn’t be found sleeping together that the dawn is visible – presaging Romeo and Juliet and Tristan und Isolde.

Consumed with Architecture Envy

I heard Mahler’s Ninth live today, for the first time since 1977 in Cleveland. I got a ticket (for an instantly sold-out concert) from the conductor, my employer, based on the fact that I wrote my senior paper at Oberlin on the piece. I analyzed the entire thing, but my paper was on the third-movement scherzo, a contrapuntal miracle. I know every note, and I registered every performance mistake. The performance was 85 minutes of me being consumed with envy. How did Mahler develop that continental sense of architecture? How did he know he could always keep going? How could he make fifteen quick key changes in a row and have every one sound fresh when there are only twelve keys? It’s a gigantic piece, yet when I’m not listening to it it telescopes back into a compact 45-minute form. How could he keep those same themes coming back over and over without ever sounding repetitive? When I listen to Ives I am filled with admiration, worship, and humility, because I’m convinced that Ives just had a brain unlike ordinary musical mortals. But what I try to do in my pieces is pretty similar to Mahler harmonically, and I can’t come close to filling out that kind of harmonic span. I feel like, intellectually, I could do what Mahler did, but I just don’t possess the imaginative energy. The sonuvabitch, how did he do it? I feel like Salieri contemplating Mozart in the film Amadeus.

The Truth About Youth

From Robin Black’s mouth to God’s ears. And even more true, if possible, about composers.

UPDATE: Allow me to amplify a little. The idea of helping young artists is an attractive one (I’ve done a lot of it myself via publicity and enjoyed doing so), and I eagerly concede Dave Seidel’s point below about the young being at a disadvantage in this economy. It’s not that I desperately need or desire the occasional $3000 cash prize. The issue is that prizes given to young composers often confer upon them a visibility that then tends to follow their careers whether they live up to their early promise or not – let alone the fact that the young composers who win them more often tend to be deft imitators than originals. And so if a composer reaches 35 or 40 without such validations, there are few possibilities to make up that advantage any other way, until finally in your 60s – if you’ve persevered – you get “discovered” by rebellious youngsters. There is no sane reason that the institutional mechanisms by which a composer can become noticed disappear before one is forty. The sentence of Robin Black’s that I identified most with (in fact I’ve written one almost identical) is her response to the MacArthur Foundation:

“I am honored to be asked and will be honored to serve — though I’ll say, as a writer who was too old while emerging for the many ‘under 40’ and ‘under 35’ awards for emerging writers, it’s practically against my religion to shift my gaze from the over-40 set.â€

I tell such organizations that there are far too many brilliant composers of my generation who’ve never received their due, and too many thirty-somethings with stellar careers, for me to look around for young composers to recommend. Any young composer offended by this will someday be a middle-aged composer, and may come to appreciate the sentiment.

Canon to the Left of Me, and Now the Right

I had a great time working on my piece Hudson Spiral (2010) last week with the Sirius Quartet, whose career I’d followed from their beginnings – although three of the four players are new since I left the Voice in 2005. It was a rare experience to walk into rehearsal and find performers completely understanding the piece, no explanation necessary, including my totalist dotted-eighth/triplet-quarter rhythms. The performance at Symphony Space last week went great. Here’s the recording. The piece is a canon at the major sixth, one of my spiral canon series. Thanks to Victoria Bond for including me on a great program.

And to bring them together at last, here’s its companion piece Concord Spiral, a canon at the minor seventh, written at the same time and played by the West End Quartet.

Minimalism Conference Deadline Extended

There was a clever joke to be made there, but I’m too foggy to come up with it. The minimalism conference being held in Finland in September has extended its deadline for paper proposals to April 15. Just follow this link, scroll down, and there’s a very convenient online submission form. I submitted a précis for my upcoming paper “Elodie Lauten as Minimalist Improviser.” Wish she were still around to enjoy it.

What Am I, Chopped Liver?

David Garland interviews my son’s black metal band Liturgy on Spinning on Air. At the end, all the band members say hello to their moms, over the radio. That’s Bernard, second from left.

David Garland interviews my son’s black metal band Liturgy on Spinning on Air. At the end, all the band members say hello to their moms, over the radio. That’s Bernard, second from left.

The Crisis in Education Today

Only one student in my theory class today recognized the song “Lydia the Tattooed Lady,” and I had to sing it to jog his memory. There is no hope.

UPDATE, 3.28.15: Sometimes I feel impelled to resolve to no longer attempt to make jokes in this space, but if I ever come to that point, there will truly be no hope indeed. I can provide more context for the above remark for people who might want it. My students often surprise me with what they know. I would be neither disappointed nor dismayed if they were unfamiliar with Oklahoma or The Music Man, but in fact their knowledge of old musicals is often broader than mine – I suppose, because people my age keep directing such musicals at their high schools. They know West Side Story as well as I do. Gilbert and Sullivan, a cultural reference far older than the Marx Brothers, is on their radar. Their familiarity with barbershop quartet exceeds what I had at their age. And they certainly know who the Marx Brothers are, which makes it the more surprising that they haven’t seen the movies. When I was in high school all my friends quoted, and sang songs from, the Marx Brothers, and I didn’t get to see the movies until I was in college – but then, the VHS and DVD had not yet been invented, so they were not available on demand. Now putting “Marx Brothers” into YouTube gives me 57,300 results, and since my students seem to spend hours a day on YouTube, I find it inexplicable that they haven’t looked up such a still-relevant cultural touchstone. Nevertheless, I do not really think that their unfamiliarity with “Lydia the Tattooed Lady” is actually the crisis in education today. The crisis in education is its underfunding by a corrupt government. I hope this resolves any ambiguity.

Feeling Played Out, but Also Played

In the next month I have five performances of my music coming up, three of them in New York City. On this coming Sunday, March 22, James Bagwell will conduct the Dessoff Choirs in three movements of my Transcendental Sonnets, 7 PM at Peter Norton at Symphony Space in New York.

On Wednesday, April 8, students of Dawn Upshaw’s will premiere my song cycle Your Staccato Ways (on poems of Karen Schoemer) at Bard College’s Bito Auditorium, at 8 PM. That’s a preview performance for the real premiere the following Sunday, April 12 at the Morgan Library and Museum, 225 Madison Ave. in New York, 4 in the afternoon.

On April 13, the Sirius String Quartet will premiere my Hudson Spiral on the Cutting Edge Concerts curated by Victoria Bond, 7:30 PM at Symphony Space.

And finally (or hopefully not finally), Relache is playing some of my Planets (Venus, Moon, Pluto) at Dickinson College at 7 PM on April 18.

There Are No Coincidences

My subject heading is from Jung. Today we went to our usual Saturday breakfast diner. Our favorite table by the window was being vacated, a young guy still sitting there. Nancy brought to my attention that the book in front of him was Music Downtown. This had never happened to me, and I couldn’t resist: “Is that a good book?,” I asked, ready to slink away quietly if he replied “Not really.” “Yeah, it’s really good!” “I wrote it,” I replied. “Really?” He looked like I had to be joking. His breakfast partner, who turned out to be his uncle and a record producer, returned, and said he had just given the book to his nephew. His nephew was a student percussionist in Pittsburgh, where I had been last weekend, and we commiserated about the awful weather. The nephew grew up in Dallas, as I did. We quickly ascertained that his parents live in the same small North Texas city as my mother, and that they go every week to the same breakfast place where my mother and brother go. After that I was afraid to press for further details.