Daily Reminder to Shut Up and Listen

Kyle Gann on music after the fact

What strikes me in rereading through vast swaths of Cage is how subjective his viewpoint is. He was always advocating pure objectivity, getting away from his likes and dislikes, but his underlying reasons for such advocacy seem to boil down to: he just liked it that way. This is not the impression I took away at 15. Cage was so tied into Marshall McLuhan and Buckminster Fuller and Joseph Campbell and everything hip that he seemed to be laying the groundwork for a permanent new paradigm shift – and woe to the loser who didn’t get on board. By upbringing and happy accident Cage preferred optimisim to pessimism, nature to personality, acoustics to metaphor, and therefore we must all prefer them too. But now I’m noticing how often his recipes for the new music ultimately get attributed, frankly, to his personal taste. I’ve started a running list of his comments in which he justified his mandates subjectively. Take the following passage, written in defensive reply to a negative 1956 review by Paul Henry Lang, and oft-quoted these days in explication of 4’33”:

For “art” and “music,” when anthropocentric, (involved in self-expression) seem trivial and lacking in urgency to me. We live in a world where there are things as well as people. Trees, stones, water, everything is expressive… Life goes on very well without me, and that will explain to you my silent piece, 4’33”, which you may also have found unacceptable.

Well, I’m with him when he rejects self-expression as a major artistic motivation. But then he takes a speciously logical but nevertheless flying leap onto the extremely thin ice of equating self-expression with anthropocentrism. What, to deal with human concerns in my music means I’m merely “expressing myself”? The only possible escape from narcissistic expression of one’s momentary emotions is to leapfrog over the entire human race altogether and write music from the standpoint of rocks and trees? This catapults out a considerable army of babies with relatively few liters of bath water.Â

Now, the attempt to de-anthropomorphize music was a fascinating project, and for a few decades it vastly enlivened the experimental music scene, as a fertile source of new processes and perceptions. I have nothing whatever to say against it. Nevertheless, most music is made by humans for the purpose of being listened to by other humans, and to posit that there is now something unworthy or inauthentic about embedding anthropocentric concerns in one’s music would be to impose stringent limitations indeed. But so it goes, with Cage endlessly elevating his personal preferences into universals, quoting Thoreau and Coomarasamy and Meister Eckhardt to mean things they never would have supported in a million years. Thus, after 1955, a painting can only be truly “modern” if it is not destroyed by the presence of dust and shadows, and only music can be truly of our time that is in no way interrupted by the noises of traffic or a crying baby. Yet I possess an otherwise wonderful 1982 Harold Budd recording rendered unlistenable by a crying baby, and I know very few composers, even ones tremendously grateful to Cage, who wouldn’t be upset by having one of their recordings marred by outside noises.

I don’t in any way mean to imply that Cage was dishonest, or even presumptuous. It is every artist’s prerogative to make a public case that his or her own aesthetic is currently the best or hippest one on the market, and more power to him or her for being a good salesman. It was the style of the time to draw universals from one’s personal preferences (something that the more relativistic composers of my own generation have noticeably refused to do). Boulez elevated his personal concerns into formulations of a new law, so did Stockhausen, so did Babbitt. If Cage’s case differs from theirs, it was in that the aesthetic he pompously attempted to impose on the world was so much more cheerful, humbler, less authoritarian, so much more open to amateurs, so much more accepting of everyday life, that one felt almost churlish in opposing it – though in the end it was every bit as subjective and contingent. That was the source of his incredible presuasiveness. His cheery, out-of-left-field openness made one yearn to agree with him, even when his pronouncements provoked an internal reaction of, “Yyyyyyyyeah, wellllllllll, buuuuuut….” His justifications provoked smiles, but didn’t, in themselves, allow for the fact that historical pendulums, having swung one way, swing back, and that the variety of human psychology is infinite. His objectivity came as a breath of fresh air after a subjective era, but to draw the seemingly invited implication that humans didn’t need both sides would have been ridiculous.Â

And actually I believe that Cage, as a person, recognized this. After the 1990 premiere of my I’itoi Variations – as un-Cagean a piece as one might care to write – he came up and complimented me warmly. The sometimes austere desiderata expressed in his books did not limit his personal relationships.Â

All I’m saying, in fact, is that Cage was in no way what he has so often been called: a philosopher. He created a remarkable illusion that he had reached some kind of Ground Zero of artistic experience. But the illusion that his new “philosophy” now exposed Beethoven, Mahler, and jazz as frauds was one that very few people ever fell for, and it is difficult for a music lover today to avoid noticing the eccentricity of his preferences. In his music he scoped out large new areas that composition had never before occupied, and in his writings he justified his explorations with stunning articulateness. But actually, it was the MUSIC that justified his explorations (when it did), not the other way around. He made no ongoing objective survey of the philosophy or psychology of musical experience; instead, he wrote the music he felt compelled to write, and then wrote with astounding beauty about why he wrote it. A philosopher would have had to account for the attractiveness of music for which he had no sympathy. I’m more of a music-philosopher than Cage was, as was my late colleague Jonathan Kramer. A philosopher starts with some objective survey of aesthetic experience and, from it, derives musical principles. Cage, like most composers (and there is no reason to judge him harshly for it), went the well-traveled opposite direction. And, since he never claimed to be a philosopher, it is no reflection on him that he did not succeed in becoming one.

My own evaluation of Cage as a composer is that he has been somewhat overrated by his champions, and, of course, infinitely underrated by his detractors. There are pieces I’m dearly attached to from every Cagean period: In a Landscape (the permanent theme song of Postclassic Radio), Dream, The Seasons, Experiences Nos. 1 and 2, the 1950 String Quartet, Hymnkus, 74, Europeras 1 and 2. Some pieces are a blast to hear live: Credo in US, Imaginary Landscapes No. 4 (which I once conducted as a student at Oberlin). Others I just don’t care for at all, notably Atlas Eclipticalis and some of the late “number” pieces. I’m not a huge Sonatas and Interludes fan, but I respect it and am always glad to hear it. Variations 4 is an unforgettable paradigm for audio collage, while 4’33” and Music of Changes are historic landmarks (like Le Marteau and Gruppen), arguably more exciting to think about than to listen to. Etudes Australes is remarkably fun to play. In short, Cage was a composer, one of astonishing variety (and the usual unevenness).Â

As for his writings, the technicolor mushroom-lined road they mapped out for us all was really only for himself alone, though he made it sound so inviting that many like-minded individuals signed up for part of the journey. He introduced me to the I Ching and opened me up to an entire world of irrationality and natural complexity. (A random-number generator plays a walk-on role in a piece I’m writing right now.) His personal ethical example left a deep, deep mark on me, though his road itself proved too breezy a route for my darker, more solitary temperament. “He was some kind of a man. What does it matter what you say about people?” But a philosopher? Not consistent enough. Not objective enough. Not rigorous enough.

Once back, I plunged into my summer project, a book on Cage’s 4’33” for Yale University Press. I’m hip deep in Cage, Rauschenberg, Daisetz Suzuki, Coomaraswamy, and the 1950s, and for perhaps the first time since I’ve started this blog, I’m inhaling a lot more knowledge than I’m exhaling. The bulk of my Cage obsession took place between ages 15 and 20 (I performed 4’33” in Dallas in May 1973), and there’s been a tremendous amount of startlingly good Cage scholarship in the last 15 years that I hadn’t seen at all – he seems to bring out the best in musicologists of all stripes. So I’m going back deeply into Cage and getting a tremendously cleaned-up perspective on him which I anticipate being creatively affected by. In my teens I became too overwhelmed by Cage’s influence and had to finally get away from him. Now I’ve got a much stronger artistic backbone, and can pick and choose, criticize and admire, whatever I fancy. He wasn’t a philosopher, and any musician who calls him that just doesn’t know what philosophers are or what they do. But he was an innovative composer with an original personality and an incredibly elegant and memorable flair for words, which latter did a tremendous amount to promote his career.

One note, though – in case it occurs to you to write in with a wisecrack that a book on 4’33” will be full of blank pages: you’re not the first to come up with that joke. Nor the 2nd, nor the 12th, nor the 50th. The fact is, I brace myself for it now, and am growing weary of it.

I had quite a few performances this spring, and the last two were by student ensembles: Bard’s chorus performing Transcendental Sonnets and the Williams College Symphonic Winds playing Sunken City. What struck me is that student ensembles really, really rehearse – and that there is NO substitute for rehearsal. The Williams College musicians, many of them non-music-majors (the flutist is going on to grad school in microbiology) worked hard from February to May, and the Bard chorus had begun rehearsing last fall. The wonderful effect was that those kids had the total sound of those pieces in their heads, knew and could anticipate every chord, every rhythmic quirk, every melody. They weren’t playing “new music,” but repertoire they knew virtually by heart. Several superb professional groups have played my music lately with considerable élan after only a few hours’ rehearsal, and I’m grateful to them. But the performances that truly gelled, that sounded the way they sounded in my head, were the ones rehearsed for months and months, and apparently that kind of luxury is only available in academia these days, with student ensembles. It gives new meaning to Milton Babbitt’s characterization of the university as “our last hope, our only hope.”

The version of Sunken City now uploaded to my web site is the Williams College one:

1. Before (Brian Simalchik, piano)

2. After (Noah Lindquist, piano)

There are many fewer mishaps here than in the otherwise heroic premiere performance by the Orkest de Volharding, which was the only recording I had previously. I was flummoxed by the ease with which the Williams College kids negotiated the constantly changing meters of 17/16, 7/8, and so on, but conductor Steven Bodner told me his secret: “Never admit to them that what they’re doing is difficult.”

Finally, a review of my latest CD by Stephen Eddins at AllMusic, and a nice, five-star one. For the record, he’s wrong about one point: there’s no 12-step equal temperament in The Day Revisited, the whole piece uses one 29-pitch scale. It’s always interesting how people’s ears attempt to deal with my crazy tunings.

This Friday, Leon Botstein will conduct the American Symphony Orchestra in Symphony No. 1 by Bernard Gann. Now, let me contextualize that statement a little. Every year just before graduation, Leon (our president) conducts his orchestra in a program of student compositions and concerto movements with student performers. This year there are four student compositions, by Craig Judelman, Kevin Gordon, Ben Richter (my student), and my son. Secondly, Bernard’s piece is about 11 minutes long and in one movement. I remonstrated with him that it was customary to simply call a piece “Symphony” until you’ve written a second one, upon which the first becomes “No. 1” retroactively. This advice took root in the manner my advice to students usually does, and the title will be Symphony No. 1.Â

I’m proud of all of our students’ compositions, but given the topic of this blog I feel compelled to publish the list of influences from Bern’s program notes:

I thank David First, my guitar/composition teacher; Erica Lindsay, my project advisor; and Kyle Gann, my father, all for providing the inspiration for my efforts here. I’d also like to thank those who have studied with in the past, including Bill Duckworth, Joan Tower, and George Tsontakis.

Some other inspirations include Julius Eastman, whose notion of “organic music” I find very useful in my method. I also think it lends itself well to reinterpretation both methodically and aesthetically. Morton Feldman, in this case as someone who on occasion composed with an attention to the visual appearance of the score as a deciding factor in how the music would sound or pace itself. Jon Gibson for composing beautifully simple sounding music. Peter Garland, whose music inspired me on a particular path about a year ago (and if I’ve left that path, I’d like to find it again). And Terry Riley, for huge shifts between “blocks” of sound, the juxtapositions between which I have for a long time greatly enjoyed, and always have had the impetus to try to employ as my imaginary ear sees it.

Eastman, Feldman, Gibson, Garland, Riley – it’s a pretty postminimalist list. The score was evaluated by Bernard’s board: our expert saxophonist/jazz composer Erica Lindsay, George Tsontakis, and John Halle from the Bard Conservatory (an entity completely separate from the Bard Music Department, don’t ask), who was the only other local composer besides myself familiar with all the composers the program notes mention. The performance is at Bard’s Fisher Center (where Bernard’s mother is general manager) Friday night at 9.Â

Also, this thursday, May 22, at 7:30, my Disklavier piece Unquiet Night will be played “live” on a program of Disklavier music at the Yamaha Piano Salon, 689 5th Ave., 3rd Floor, Manhattan. Organized by composer Gordon Green, the program includes works by Chris Dobrian, Steve Horowitz, David Jason Snow, and Green himself. Unquiet Night is more totalist than postminimal.

This quotation from G.K. Chesterton, posted as a comment to Glenn Greenwald’s heroic column at Salon.com, is too apropos not to help circulate:

It may be said with rough accuracy that there are three stages in the life of a strong people. First, it is a small power, and fights small powers. Then it is a great power, and fights great powers. Then it is a great power, and fights small powers, but pretends that they are great powers, in order to rekindle the ashes of its ancient emotion and vanity. After that, the next step is to become a small power itself.

Meanwhile, I’m working 12-hour days at Bard trying to get all the seniors graduated. Like giving birth to dodecatuplets, only bigger. See you when the semester’s over.

New today on Postclassic Radio: a rare Charlemagne Palestine Voice Study from the mid-’60s, pianist Ana Cervantes playing music by Alex Shapiro, Arturo Marquez, and Laurie Altman, other pieces by Shapiro from her Notes from the Kelp CD, music by David McIntire, Matt Le Groulx, Redhooker (Stephen Griesgraber, composer), and Brian Nozny, plus Andrew Violette’s Rave in its scintillating 75-minute entirety. Fantastic stuff. Wish I had time to listen.

Very big week for my music coming up next week.

At long last composer Julio Estrada tells me that my book on Conlon Nancarrow is now available in Spanish, from the University of Mexico Press. I’m awaiting a copy in the mail. Here (in the right column) is the only advertisement I can find for it. Espero que seas ayudado por esta publicación.

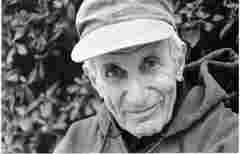

Neely Bruce informs me that the great Henry Brant has died within the last few hours. He was a phenomenally creative figure, though one hard to wrap one’s ears around, because his specialty was spatial music; his works, often involving multiple ensembles separated by distance, were too enormous to stage often, and recordings hardly do them justice. I was privileged to have heard his 500: Hidden Hemisphere live, a mammoth piece in celebration of Columbus for three wind ensembles and steel drum band, placed around the fountain at Lincoln Center in 1992. He was born in Montreal, and thus Canada gets to claim him, but his primary inspiration was Charles Ives, and he began composing for instruments widely separated from each other in an attempt to clarify dense, Ivesian polyphony. Even when not writing spatially he composed for unconventional ensembles, like the ten variously sized flutes of his delightful Angels and Devils (1931), or his Orbits (1979) for 80 trombones, organ, and sopranino voice. A work called Fire on the Amstel employs four boatloads of 25 flutes each, four jazz drummers, four church carillons, three brass bands, three choruses, and four street organs. Live performances of it remain rare, for some reason. His reputation as an incredible orchestrator (he made part of his living doing filmscores from the 1930s through ’60s, but didn’t like to talk about them) was confirmed with his 1994 orchestration of Ives’s Concord Sonata, titled A Concord Symphony, a splendid reimagining of a great work.Â

Neely Bruce informs me that the great Henry Brant has died within the last few hours. He was a phenomenally creative figure, though one hard to wrap one’s ears around, because his specialty was spatial music; his works, often involving multiple ensembles separated by distance, were too enormous to stage often, and recordings hardly do them justice. I was privileged to have heard his 500: Hidden Hemisphere live, a mammoth piece in celebration of Columbus for three wind ensembles and steel drum band, placed around the fountain at Lincoln Center in 1992. He was born in Montreal, and thus Canada gets to claim him, but his primary inspiration was Charles Ives, and he began composing for instruments widely separated from each other in an attempt to clarify dense, Ivesian polyphony. Even when not writing spatially he composed for unconventional ensembles, like the ten variously sized flutes of his delightful Angels and Devils (1931), or his Orbits (1979) for 80 trombones, organ, and sopranino voice. A work called Fire on the Amstel employs four boatloads of 25 flutes each, four jazz drummers, four church carillons, three brass bands, three choruses, and four street organs. Live performances of it remain rare, for some reason. His reputation as an incredible orchestrator (he made part of his living doing filmscores from the 1930s through ’60s, but didn’t like to talk about them) was confirmed with his 1994 orchestration of Ives’s Concord Sonata, titled A Concord Symphony, a splendid reimagining of a great work.Â

This afternoon we were analyzing movement VII of the Quartet for the End of Time, and came upon a passage using, for the only time in the piece, the following mode of limited transposition, which I asked the class to identify:

OK. I’ve finished The Planets, and so I’m listening, once again for the 30th time, to John Coltrane’s closely related Interstellar Space album, with just himself and Rashied Ali on drums. I love Coltrane, of course, as who doesn’t? Black Pearls, A Love Supreme, Ascension, Giant Steps, My Favorite Things, Ballads, they’re all among my favorite jazz albums. But Interstellar Space I admit I have trouble figuring out. Mars and Venus should be polar opposites, but I have trouble finding much variety of mood or method on this CD. What am I missing? Postclassic is possibly not the right venue, but can anyone tell me how to listen to this last Coltrane disc (1967) and find it as wonderful as his earlier work?Â