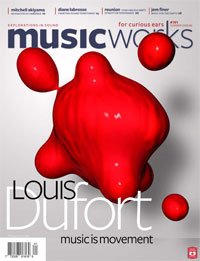

This month’s Musicworks magazine contains an interview with me, written by editors Gayle Young and David McCallum, and titled “Pitch and Rhythm Guy,” which is something I called myself during the course of the interview. The accompanying disc contains two pieces of mine, the final scene of Custer and Sitting Bull in its sparkling new rendition with the sounds redone by M.C. Maguire, and a keyboard piece called Triskaidekaphonia, which I’ve written about here before. Gayle and David generously let me ramble on about my music, including my relationship to jazz harmony, astrology, microtonality, American Indian music, and so on. I feel I internalized pretty early in life that the next thing to do in music was to find new subtlety and new kinds of organization in music’s two highest-profile parameters, pitch and rhythm – just as most of the music world was giving up on those directions as having been perhaps exhausted, though there were a number of composers of my generation who made a fetish (in the best sense) of performable rhythmic complexity.Â

This month’s Musicworks magazine contains an interview with me, written by editors Gayle Young and David McCallum, and titled “Pitch and Rhythm Guy,” which is something I called myself during the course of the interview. The accompanying disc contains two pieces of mine, the final scene of Custer and Sitting Bull in its sparkling new rendition with the sounds redone by M.C. Maguire, and a keyboard piece called Triskaidekaphonia, which I’ve written about here before. Gayle and David generously let me ramble on about my music, including my relationship to jazz harmony, astrology, microtonality, American Indian music, and so on. I feel I internalized pretty early in life that the next thing to do in music was to find new subtlety and new kinds of organization in music’s two highest-profile parameters, pitch and rhythm – just as most of the music world was giving up on those directions as having been perhaps exhausted, though there were a number of composers of my generation who made a fetish (in the best sense) of performable rhythmic complexity.Â

From Gamma to Ut

John Luther Adams writes in with a note about using gamuts in composition:

The use of gamuts is among the most practically useful aspects of our inheritance from Cage.

When we freeze the tonal space, we shift the focus of our music away from the manipulation of notes to listening to the sounds. It doesn’t matter whether the elements of a particular gamut are obviously related at the outset. When we hear the music, we hear the continuity, the continuum of the sounds. The use of interval controls (a la Harrison) does something similar. In fact, I often use interval controls to create my gamuts. So Lou’s observation to Daniel Wolf [see comments] makes good sense to me.

Cage Query

[UPDATED] In February of 1948, John Cage gave a lecture at Vassar, heralding his intention to write a silent piece:

I have, for instance, several new desires (two may seem absurd, but I am serious about them): first to compose a piece of uninterrupted silence and sell it to the Muzak Co. It will be [3 or] 4 1/2 minutes long – these being the standard lengths of “canned” music, and its title will be “Silent Prayer.”

Probably this is too simple, and admittedly I don’t know about the exact technology used by Muzak, but I don’t think it’s quite coincidental that 3 and 4 1/2 minutes are about the limitations of the 10-inch and 12-inch 78 rpm records of the day.

Wheels Turning

I’m beginning to wonder whether there is any discernible theoretical difference between Cage’s “gamut” technique of the 1940s, by which he precompositionally limited what sonorities he would have available, and what I’ve been calling postminimalism all these years. I’ve been tempted all along to refer to Cage’s pieces like The Seasons and In a Landscape and the 1950 String Quartet (and even Feldman’s 1951 string quartet Structures) as “protopostminimalist,” but now I’m beginning to question what purpose the “proto-” serves. If there is a difference, it’s that the postminimalist limitations of Bill Duckworth’s music, and Janice Giteck’s, and John Luther Adams’s, tend to fall within a system, or a scale, or a logical set of rhythms deployed over a certain range, while Cage selected the elements of his gamuts for maximum disjunction and diversity. But that’s a tenuous disctinction, and when you get to a totalist work like, say, Michael Gordon’s Thou Shalt!/Thou Shalt Not! or Mikel Rouse’s “Tennessee Gold,” even that falls apart. Could one, I’m thinking, draw a line extending from Satie through Cage and Feldman – skipping over or around both serialism and minimalism – to the postminimalists, showing the rise of a new way of thinking about music, as a nonsyntactic play among discrete sonic objects?Â

Dunno Why They Read Me, I’m Being as Esoteric as I Can

Two years ago when Scott Spiegelberg started his Technorati-based ranking of classical music blogs, PostClassic came in at number 5. Last year I was down to number 8. This year, I’m back at number 5 again. Blogs come, and blogs go, but ol’ Gann just keeps hangin’ in there.

Academy d’Underrated: Ljubica Maric

For instance, did you know that a Serbian composer, Vladan Radovanovic, claims to be the first minimalist composer, having started in 1957? (I’m really sorry that I can’t provide Serbian diacritical markings, but my word-processing software isn’t up-to-date enough to handle them, nor am I confident that Arts Journal could represent them.) Dragana runs into him occasionally, and he’s miffed that she hasn’t credited him yet. And here’s national composer Stevan Stojanovic Mokranjac, pictured on the country’s 50-dinar note (about a dollar):

(The 100-dinar note boasts national hero Nicola Tesla, who figured out a lot about electricity before Edison did.)

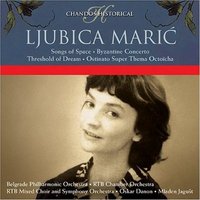

But easily the most fascinating story in Serbian music history is that of Ljubica Maric (1909-2003, pronounced Lyubitsa Marich, with a “ch” like church and accents on both first syllables). She was Serbia’s most important and innovative modernist composer before World War II. Now, how many other countries can claim that their pioneering modernist composer was a woman? Like, zero? Gotta hand it to Serbia. And, to be a chauvinist pig about it for a moment, early photos like the CD cover here show that Maric was just about the most beautiful composer in the history of music, strikingly modern-looking in the 1930s. She lived to be 94, and Dragana used to see her at concerts, but was too shy to speak to her.

But easily the most fascinating story in Serbian music history is that of Ljubica Maric (1909-2003, pronounced Lyubitsa Marich, with a “ch” like church and accents on both first syllables). She was Serbia’s most important and innovative modernist composer before World War II. Now, how many other countries can claim that their pioneering modernist composer was a woman? Like, zero? Gotta hand it to Serbia. And, to be a chauvinist pig about it for a moment, early photos like the CD cover here show that Maric was just about the most beautiful composer in the history of music, strikingly modern-looking in the 1930s. She lived to be 94, and Dragana used to see her at concerts, but was too shy to speak to her.

Maric studied with Josip Slavenski (1896-1955), who had absorbed Bartok’s ideas about incorporating folk music into symphonic music, and there is a strong Bartokian streak to Maric’s music, though the folk music influence is rarely obvious. She later studied in Prague with Alois Haba of quarter-tone fame, and wrote some quarter-tone music which is unfortunately lost. She got rave reviews for a wind quintet played in Amsterdam in 1933, and spent some time conducting the Prague Radio Symphony. But World War II interrupted her career, and afterward she was inhibited by Yugoslavian communism’s antipathy toward modernism, so that her total output is rather small. She revved up her muse again in the late 1950s, however, and the only works I’ve heard of hers, on the pictured Chandos disc, are from the period 1956-63. The most immediately engaging of them is her Ostinato Super Thema Octoicha (1963), which is based on a repertoire of Byzantine medieval religious songs called the Octoechos; I’ve uploaded an mp3 of it for you here. The Byzantine Piano Concerto and Sounds of Space contain remarkably beautiful and original passages as well; she very much had her own voice.

Teaching at the Stankovic School of Music and then at Belgrade Conservatory, Maric was into Zen and Taoism, and lived a reclusive life despite interest shown in her music by Shostakovich, among others. From 1964 to ’83 her pen fell silent, then she started composing again. She made some tape music performing on not only violin but cutlery, jewelry, and dentist’s equipment, but refrained from ever releasing it. She was a fascinating figure, Serbia’s Ives, Crawford, Bartok, and Cage all rolled into one. There’s a scholarly essay by musicologist Melita Milin about her career in the 1930s here. It all makes me think that the Balkan countries need to be more regularly incorporated into the historical narrative of 20th-century music.Â

A Triumph of Musicology

Amazingly, composer Mary Jane Leach now has all of the late Julius Eastman’s available scores up as PDFs online, including the much-rumored symphony which, in predictable Eastman style, is titled Symphony No. 2. Good luck deciphering them. There is also a cleaner, annotated score of Crazy Nigger, significantly easier to read, made by Dutch composer-pianist Cees Van Zeeland, who arranged a performance of the piece this spring. I also have in my possession my own arrangement of Gay Guerilla for nine guitars, which I would be happy to send a PDF of to interested parties. It’s an amazing musicological feat for a composer whose scores were thrown out into the street in the 1980s by the sheriff who evicted Eastman from his apartment, sending him to live in Tompkins Square Park. Those of us who mourned Eastman’s death thought none of that music would ever be seen or heard again.

Tidbits

A few random notices:

When Playing the Notes Is Enough

I’ve been looking for newer recordings, on CD. But every other recording I find is too fast, too textural, too “expressive,” too classical – too Uptown. They’re ultrasimple pieces, all white keys, nothing but pentatonic scale in No. 2. As with much of my own music, I sense that classical musicians find the bare notes too uninteresting, and think they have to “interpret” them to breathe life into them. There seems to be no sense anymore that a pure, stately, slow melody (such as one finds in Renaissance polyphony or Japanese Gagaku) can be beautiful. Post-Ligeti, post-Carter, post-Debussy, everything has to be turned into texture, into an illusionistic surface that transcends the notes. No! No!, a thousand times no! Sometimes the notes, played slowly and with dignity and clarity, are all one needs, as in Socrate, as in Musica Callada, as in In a Landscape, as in Snowdrop, as in Symphony on a Hymn Tune, as in The Art of Fugue.Â

It strikes me, though this would be difficult to document, that the ’70s were a high point for performers understanding that principle, and we’re now in a deep trough, because lately I’ve had a difficult time getting performers to play my simple music slowly enough; they encounter so little technical challenge that they start to rush, trying to buoy what they fear is dull music through some hint of the virtuosity they’re so proud of. But such music turns trivial when played as quickly as it’s easy to play it, as does much of Cage’s music of the 1940s. Bernas and Wyatt and Eno, coming from the pop world, exhibit far and away a more instinctive understanding of the Zen simplicity Cage was aiming at than any of the more recent renditions. I fear I’ll never find another really beautiful recording of Experiences 1 & 2 again.

An odd thing about Experiences No. 2 is that Cage omitted the final two lines of Cummings’s Sonnet, which I think are the best lines:

turning from the tremendous lie of sleep

i watch the roses of the day grow deep.

But it’s still a gorgeous song, and most gorgeous of all when sung the clean, blank way Wyatt sings it.

How to Write Your Own John Cage Story

My mother used to teach piano, and got her Master’s Degree in music ed. One summer when I came home from Oberlin, I brought her a cassette tape of the music I had had performed during the year. She played it, and didn’t say much right away. Later that day, she suddenly sighed with relief and said, “I’m so glad you’re not writing 12-tone music.”

Now, imagine me reading that slowly, with pauses between the phrases, and with David Tudor making electronic noises in the background. Doesn’t that sound like it could fit in the recording Indeterminacy? Or try this one:

Ben Johnston’s priest advised him to try out Zen meditation, but the closest Zen temple was in Chicago. Ben began driving to Chicago every week, and so I would meet him at the temple for my composition lesson after the Zen services, rather than drive down to Urbana. During lessons, Ben’s colleague Heidi von Gunden would serve us tea in traditional Japanese manner. Finally I began showing up two hours early, to go through the Zen services with Ben. After each session of zazen, my compositional inspiration would suddenly open up, and my head would be flooded with musical ideas.Â

Later, when I moved to New York, I attempted to keep up my Zen practice. The monks at the New York temple, however, quite opposite to the ones in Chicago, looked down their nose at meditators who needed pillows to sit on, or who couldn’t make it through a 45-minute session without being struck on the shoulders. Put off by their snobbishness, I never went back.

I’ve never thought of my life as being the kind susceptible to story-telling, but plunging back into the stories that Cage sprinkled liberally throughout his early books has made me rethink. All you have to do is isolate some comment you remember, or event or change of mind, state it flatly with no affect in as few words as possible (or with an optional colorful phrase or two), and – most important of all – without context. By doing so, Cage spread such a Zen flavor around these stories, like they were koans, making his life seem like a series of nonsequiturs in which all the people around him were slightly crazy. Memorized by musicians of my generation and repeated by every biographical commentator for lack of better documented information, these stories stand almost as a smoke-screen against those trying to get insight into Cage’s life. So many of them end in absolutely opaque punchlines that cry out for explication:

“We don’t know anything about her coat. We didn’t take it.”

“You know, I love this washing machine much more than I do your Uncle Walter.”

“You’re too good for us. We’re saving you for Robinson Crusoe.”

Recognize them all, don’t you? And though he didn’t start publishing them until the age of 49, all those enigmatic little stories seemed so perfectly hip for the upcoming ’60s decade whose humor would be defined by nonsense and nonsequiturs like the ones spearheaded by the TV show Laugh-In. It was an amazing anticipation of the ethos of a new era, and reminds you that in his brief career at Pomona College, Cage was known, not as a musician, but as a short-story writer. It strikes me that the stories in Silence had every bit as much to do with Cage’s exploding popularity as the actual lectures and essays did. His sense of style was elegant and irresistible, but, as it turns out, entirely imitable. I’ll try one more:

In college I had a tremendous crush on a student actress I’ll call Leona. To say the crush was unrequited would be an understatement. One day in the library I ran across her kissing another woman, and decided that was the reason. Almost twenty years later, however, I was talking to my college friend Bill Hogeland, and Leona came up. Bill admitted that he had had an affair with Leona after graduation, but added that she made him uncomfortable because she worked in a strip club.

UPDATE: All right, maybe that last one is a Morton Feldman story. I’ll try another, though one you’ve heard here before:

It was the dress rehearsal for the opening night of New Music America. At Orchestra Hall, Dennis Russell Davies was rehearsing members of the Chicago Symphony, who were having a difficult time negotiating the constant meter changes of Steve Reich’s Tehillim. The rehearsal was to end at 5, and as the hour approached, Reich stood up and announced that the piece wasn’t ready, that another hour’s rehearsal would be required. Maestro Davies looked out into the hall for a representative of the festival, and found only myself, administrative assistant, aged 26. He asked for permission to keep the orchestra onstage another hour. I ran out into the lobby and tried, without success, to locate the festival directors by phone. Not knowing what else to do, I walked back in and, as though someone with authority had told me to do so, shouted, “Go right ahead!” The performance went fine, and no one ever mentioned, on that day or any other, the extra $15,000 that my “go-ahead” cost the festival.

Everything’s Up to Date

We’re inviting all scholars working in the area of minimalist music to submit proposals of papers for presentations of 20 minutes each. Possible subjects include, but are not limited to, the following:

– both American and European (and other) minimalist music;Â

– early minimalism of the 1950s and ’60s;Â

– outgrowths of minimalism into postminimalism, totalism, and oher movements;

– minimalist music’s relation to pop music or visual art;Â

– performance problems in minimalist music;Â

– analyses or investigation of music by La Monte Young, Terry Riley, Steve Reich,

Philip Glass, Arvo Pärt, Louis Andriessen, Gavin Bryars;Â

– especially encouraged are papers on crucial but less public figures such as

Tony Conrad, Phill Niblock, Jon Gibson, Eliane Radigue, Rhys Chatham, Barbara Benary, Julius Eastman, and so on.

Deadline for proposals, from 300 to 500 words, is October 31, which should be e-mailed toÂ

kgann@earthlink.net (Kyle Gann)

andÂ

compositeurkc@sbcglobal.net (David McIntire)

The committee to select papers will consist (as of now) of myself, Keith Potter, Pwyll ap Sion (codirector of the first conference, and author of a new book on Michael Nyman), and Andrew Granade.Â

The first such conference was a tremendous success. We all enjoyed being able to talk freely to academic colleagues about repertoire not always granted much respect in academia. This time we’ve got some dynamite performances lined up, including some seminal minimalist works that haven’t been heard publicly in decades. We’ll be sending this invitation out via various mailing lists shortly, but this is the first public announcement. Please spread the word to anyone you think would be interested. Mikel Rouse has promised to treat us to the world’s best barbecue, which apparently can be found in Kansas City! We’ve gone about as fer as we can go.

I Have Nothing New to Say and I Am Saying It

…and that is commercialism as I need it. I have ongoing doubts about the propriety of taking off three months of my life to write a Cage book. I never aspired to be a Cage scholar. By the late ’80s so many people were doing excellent work on him that I just bowed out. I have a phobia about competition, and I despise duplicating the work of others. I got a blast from analyzing all of Nancarrow precisely because I was learning so many things no one else yet knew. Years ago Oxford asked me to write a Charles Ives biography. Few things would have given me greater pleasure than spending two years immersed in Ivesiana, but Jan Swafford’s superb biography had just appeared, and the idea of taking all that time away from composition to awkwardly paraphrase what Jan had already said so eloquently just wasn’t conscionable. Yet here I am, and I have nothing to say about 4’33” that hasn’t been said before, and better. If I come up with a single original insight by the time I finish this book, I’ll be as surprised as anyone.Â

Luckily, the book is intended for a general audience. It’s part of a Yale University Press series called “American Icons.” The other volumes in process so far concern the Empire State Building, the Superman comic book series, and the Marlboro Man. This last sounds like the one to bet on: the Marlboro Man was invented because Marlboro started out as a women’s cigarette, and they started trying to market it to men. But then the Marlboro Man (before he got lung cancer) became a gay icon, so in a sense he came full circle. How much more fun does that sound like than a book on five minutes of silence?

The sad fact is, though, that this book will advance my reputation in musicological circles far more than the postminimalism book I should be working on. As I’ve noted often before, a musicologist’s reputation is proportionate to the square of the fame of the composer he’s an expert on. Explaining Mikel Rouse and David First and Eve Beglarian to the world will make me more an oddity than an expert. Writing a Cage book won’t put me up with the Beethoven and Bach savants by a long shot, but it will zoom me up near the top of the relatively small 20th-century heap. Quality and content play little part in this dispensation.

And yet that’s not at all why I’m doing it: I’m more doing it in spite of that. I would rather spit in the eye of every musicologist in Christendom than lift a finger to achieve status in such an artificial, unthinking heirarchy. A couple of friends have been kind enough to tell me that I’m a better composer than writer, and I would like to think so. Personally, I believe that my most important contribution to the world is the extent to which I have developed just intonation into a broader musical language, with deep roots in tonal practice and tremendous ramifications for future usage, and if I had my druthers, which I don’t, I’d infinitely prefer to be remembered for that. I have no ambitions at all as a musicologist, beyond righting the wrongs that good composers of my generation have suffered.

So why am I doing this? Because the opportunity arose, offered by an editor who’s an old friend, with a generous advance attached, and, in a Cagean spirit, I grabbed it. Because Cage played a tremendous role in my youth and only a peripheral role in my adulthood to date. Because Zen was a wonderully energizing influence on my life in the ’70s and early ’80s, and I’ve been too long divorced from it. Because he was a wonderful man, and his personal example laid an indelible imprint on my life. (Among other things, I think I absorbed from Cage the lesson that being a prolific and controversial writer can help augment one’s reputation as a composer.) So ultimately my motivations are self-serving, in the deepest possible sense: to get back to my roots, to backtrack over where I came from, to figure out why, at age 17, performing 4’33” in public seemed like such an important thing to do. To revisit those high school days in which I enthusiastically played the Everest recording of Variations IV for my theory class, with my teacher and classmates all terribly dubious as to whether that was actually music. As of June 8 I’m at the beginning of a new 30-year astrological cycle in my life, and I needed to reorient myself. I’m at a lull in my compositional activity, with many large projects just completed and new ones still vague in my mind. And I’m hoping, hoping against hope, that newly understanding 4’33” and the rest of Cage’s post-1950 output, as an adult, will propel me, as a composer, in a new and hopefully completely unexpected direction.

How Nazism Created the Current Republican Party

As part of my Cage research, I’m reading Aldous Huxley’s The Perennial Philosophy (1945), which Douglas Kahn (in “John Cage: Silence and Silencing,” in the Winter, 1997, Musical Quarterly) claims Cage read shortly before writing 4’33”. I don’t recall Cage ever mentioning Huxley in his writings; I’d be interested if someone can point me to an instance. Kahn certainly makes a good case for Huxley’s influence, which is similar to Coomaraswamy’s in this respect.Â

But what moves me to buh-loggg today is a passage in the chapter “Religion and Temperament.” The book is a survey and comparison of the great religious traditions, with their commonalities drawn out via copious quotation. As implied, the chapter in question deals with the observation that religious experience is highly dependent on personal temperament; that despite the one-sidedness of certain religious expressions, the path to Truth is not a one-size-fits-all phenomenon. According to Huxley, the world’s religions have implicitly acknowledged three types of character. Few people are purely one type, and most of us have a mixture, but here, with their defining characteristics, are the three extremes he outlines, with an exotic terminology from I don’t know where:

viscerotonic: “indiscriminate amiability and love of people as such; fear of solitude and craving for company; uninhibited expression of emotion;… craving for affection and social support….”

somatotonic: “love of muscular activity, aggressiveness, and lust for power; indifference to pain; callousness with regard to other people’s feelings; a love of combat and competitiveness; a high degree of physical courage….”

cerebrotonic: “the over-alert, over-sensitive introvert, who is more concerned with what goes on behind his eyes… than with that external world… Cerebretonics have little or no desire to dominate… they want to live and let live and their passion for privacy is intense… For him the ultimate horror is the boarding school and the barracks….”

That “boarding school and barracks” line pinpointed me as a stereotypical cerebrotonic in short order. Going through the world’s religions, Huxley outlines which ones offer more sustenance to, and are more congenially followed by, each of these three temperaments. All very interesting, perhaps questionable, but what struck me was his closing statement (and remember this was written in 1945, as the war was just winding down):

Nazi education, which was specifically education for war, had two principal aims: to encourage the manifestation of somatotonia in those most richly endowed with that component of personality, and to make the rest of the population feel ashamed of its relaxed amiability or its inward-looking sensitiveness and tendency toward self-restraint and tender-mindedness. During the war the enemies of Nazism have been compelled, of course, to borrow from the Nazi’s educational philosophy. All over the world millions of young men and even of young women are being systematically educated to be “tough” and to value “toughness” beyond every other moral quality. With this system of somatotonic ethics is associated the idolatrous and polytheistic theology of nationalism – a pseudo-religion far stronger at the present time for evil and division than is Christianity, or any other monotheistic religion, for unification and good. In the past most societies tried systematically to discourage somatotonia. This was a measure of self-defense; they did not want to be physically destroyed by the power-loving aggressiveness of their most active minority, and they did not want to be spiritually blinded by an excess of extraversion. During the last few years all this has been changed. What, we may apprehensively wonder, will be the result of the current world-wide reversal of an immemorial social policy? Time alone will show. (pp. 160-161, emphasis added)

Time alone, indeed. As an explanation for Bill O’Reilly, Rush Limbaugh, the Bush administration, and the neocons, this is insufficient; it would account for their love of bullying and contempt for perceived weakness, but not their unfathomable venality, mendacity, and hypocrisy (where were “courageous men of aggressive action” when New Orleans was drowning?). But the rhetorical emphasis on “toughness” is certainly an oversized component of our political discourse, and I think we as Americans – especially since Reagan’s 1980 election – have often been made ashamed to loudly voice sympathetic or altruistic impulses. And I can imagine Cage, a self-described “sissy” who was so often beaten up by bullies as a child, finding personal resonance here.