I feel bad that an upcoming minimalism conference co-directed by myself, of all people, has been criticized for its absence of attention to woman composers. I don’t quite know how to go about addressing the collective guilt of the musicological field. As I said in the comments, I don’t know why Meredith Monk, not to mention Pauline Oliveros and Elodie Lauten, get so little attention in the nascent scholarly attention paid to minimalism. Monk’s scores, when she uses them at all, don’t really circulate; I managed to coax one of her opera Atlas from her, and I occasionally teach it. Still, there are a lot of scholars less score-oriented than myself who could put together a good paper on Monk’s distinct and original performance practice. (In Atlas, the instrumental accompaniments and some vocal lines are written out, but much of the vocal writing, including choral material, is developed in rehearsal, depending on the attributes of the singers available. Meredith prefers to teach her parts vocally, without the dehumanization of paper mediation.) Talking about the subject, composer Bernadette Speach once told me that in New York women composers come to men composers’ concerts, but that men rarely showed up to hear women; I started taking count, and found she had pretty much hit the nail on the head.

When Students Cancel, You Have Time to Think

A couple of insights gleaned from recent teaching:

– In my 20th-century orchestral repertoire class I happened to start teaching the minimalists on the same day I finished up the style-mixing postmodernists, like Bolcom, Rochberg, Del Tredici, Jonathan Kramer. And it occurred to me what they have in common. Both groups place the locus of innovation (I can still write fluent academese when I need to, though the Voice trained me out of it and I have no desire to start up again) – both rely for a sense of newness on the amount and variety of information in their pieces, contrasting it with the general information rate and stylistic variety range of the typical classical piece. The minimalists pare down the information to give you less than classical listeners would expect. The postmodernists ramp up the information variety so that you’ve got Mozart quotes, country and western licks, Romantic clichés, jazz all bubbling around in the same mix. There remain, of course, many composers for whom the information rate of classical music is still an abiding paradigm, but the minimalists and postmodernists likewise rebelled against the general rhetoric of classical music – one group by narrowing the focus, the other by widening it. Diametrically opposed as the two reactions are, I sense a certain kinship there, a tiredness with the repetitiveness of the classical music experience.

– Wagner’s spinning of Tristan und Isolde out of a dramatically small group of materials – the Tristan chord, deceptive cadences, and French sixths morphing into dominant sevenths that never conclusively resolve – of course led the way to atonality, a divorce from the universal syntax of the common practice period, and 12-tone music’s tendency to derive every element from a single row. More than that, though, I think it destroyed an overall faith in a commonly shared, objective musical language and created – indeed, privileged – a paradigm by which the composer creates his or her own universe for each work. This, seems to me, is what separates the New Tonality from the old. I write a lot of tonal music, but I never plunge into the whole syntax of V-I cadences, circle-of-fifths progressions, and all that stuff one learns in school: for each piece I choose what elements, some familiar and some piquant, that will constitute my language for that work. One can certainly say this for postminimalism in general, and I imagine for other New Tonal music as well. Wagner’s stripping his Tristan music of so many of tonal music’s usual signifiers was (forgive me for putting it this way) a proto-postminimalist gesture, or perhaps we should just say minimalist: a virtuoso determination to draw as much length and variety as possible from an artificially circumscribed set of chords and voice-leadings.

In this sense I feel as a composer that I still inhabit a post-Tristan world more than I do, say, a post-Rite of Spring world. The expansion and increased systematization of materials ushered in by Le Sacre strikes me (when composing) as a little musty and superceded by this point. But Tristan seems like a forever-locked door, beyond which one could never again return to a non-contextual common language whose references could be drawn from a vocabulary not created within the piece itself.

Not a Joke, the Date Notwithstanding

Life has been too hectic lately (in mostly good ways) to be attentive to my own PR. I do have a performance tonight, and a local one. The Da Capo ensemble gives their “Celebrate Bard” concert tonight (I affectionately call it “Calibrate Bard,” on the rationale that it shows us how we’re doing), at 8 PM in Olin Auditorium on campus. The program is as follows:

John Boggs ’09 ~ This Estranged Land

Cameron Bossert ’06 ~ Celeritas

Brian Fennelly ~ Sock Monkeys

Kyle Gann ~ Kierkegaard, Walking

Casey Hale ’02 ~ of Another

Joan Tower ~ Amazon

All Politics Is Local

I live in New York’s 20th congressional district, upon which the eyes of the nation are riveted at the moment as Democrat Scott Murphy and Republican Jim Tedisco battle it out to fill Kirsten Gillibrand’s empty seat. Many are trying to make this a referendum on the Obama administration. But the truth is, nothing Obama has done since taking office could have swayed any vote in my county one way or the other. Half the county is local rednecks descended from families who’ve lived here forever, and they despise the other half: New York cityfolk who moved up here from Manhattan, along with academics like me at the local colleges. The cops are all Republican. Get stopped for speeding, and if you can prove your area code isn’t 212, you might get let off. Recently at a political rally, a woman Democrat started arguing with a Republican man, and the Republican punched her in the nose: the police, of course, arrested the woman for disturbing the peace, and the Republican judge ruled against her. Bard students peacefully protested after the 2004 election, and police wrestled them to the ground, after which the local Republican judge threw the book at them. At a city meeting at my town, a distinguished older gay citizen (formerly from the city, of course) spoke and got called “faggot” by one of the police, who hustled the gay man off to jail for the crime of speaking his mind – and the worse crime of not having originally been from around here.

Draw a Straight Line and Follow It

Well, the Second International Conference on Minimalist Music committee has gone through all the paper proposals, and we’ve put together a program of about 56 papers. It’s a stunner. I’m really proud of the lineup, especially because it exhibits an intelligently varied yet limited range of minimalism. Yes, there are ten papers that talk about Steve Reich, but there are no fewer than four on Phill Niblock (!), two on Julius Eastman, also two each on Michael Gordon, David Lang, and Arvo Pärt, one each on Jim Fox, David Borden, Michael Torke, Jim Tenney, and Charlemagne Palestine. (Not that Niblock doesn’t merit it, quite the contrary, he’s a vastly influential underground figure; but I’m impressed that so many academics latched on to someone so quintessentially Downtown, in all literal and metaphorical senses.) We have musicologists coming from the UK, Canada, Belgium, Australia, the Czech Republic, Serbia, and France. There are even papers on minimalist aspects of Morton Feldman and Milton Babbitt – we could have turned down the latter in good conscience, but I’m just too curious. And the performance part of the conference is geared around little-known but often historic early minimalist works: an early Terry Riley piece that’s only been played twice before, some rare Tom Johnson opuses, my own reconstructions of 1959 Dennis Johnson and 1982 Harold Budd, performances by Palestine and Mikel Rouse, and a few surprises we’re still cooking up. This is going to come very close to defining minimalism as I hear it: not a watered-down catch-all term that includes everything from Wagner’s Rheingold to Donna Summer, but a true tradition among people who knew each other and exchanged ideas during an intense historical period. It’s the most exciting thing in my immediate future. Kansas City, September 2-6: be there or be neoromantic.

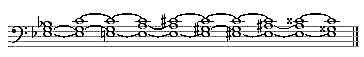

Reconstructing Harold

Here’s a brief audio sample from Harold Budd’s Children on the Hill, the improvisatory piece I’m transcribing from a 1982 perfomance for reconstruction on our upcoming Minimalism conference. At 23 minutes in length, it’s a completely different piece than his eponymous performance on the old Obscure CD. The beginning and end were easy to transcribe, but in the middle of the piece is a wildly rhapsodic wash of arpeggios that goes on for 13 minutes. I can slow down the soundfile to catch all the notes, but slowing down also blurs the note attacks, and makes low notes in particular less distinct. So what I end up doing is transcribing the general outlines as far as I can at normal speed, slowing down to 50 or 60 percent to catch all the treble arpeggios, then slowing that down another 50 percent to decipher grace notes and disentangle rippling arppeggios, then listening to the whole thing sped up again – which often reveals mistaken rhythms as well as mis-heard bass notes. Of course, it’s not just normal piano, but piano played through an Eventide Harmonizer, which blurs the notes and makes them sound like they’re sustained or played again, which doesn’t make transcription any easier. I’d say I’ve been spending at least three hours on every minute of the recording, and I’ve got seven minutes left to go. Below is my transcription (so far) of the passage above. Of course, rhythms are kind of a humorous fiction in a rapidly improvised passage like this, so the pianist (Sarah Cahill) will have to ignore the meter, play in an unmeasured rush of excitement, and listen to the original recording to try to capture the original expression. Next to this, the transcription work I did on The Well-Tuned Piano was a piece of cake, but Harold’s music is so beautiful that it’s going to be totally worth it.Â

Where It’s Warm Enough to Move One’s Fingers

Tomorrow night at 8, Wednesday, March 25, pianist Justin Kolb will play some of my Private Dances along with Beethoven’s Appassionata Sonata at the PHCC Performing Arts Centre in New Port Richey, Florida. Also on the program are pieces by Victoria Bond and Stella Sung, as well as some Liszt arrangements of Mendelssohn songs and Bernstein’s piano-ization of Copland’s El Salon Mexico. It’s not often I find myself in such company. Justin, with whom I’ve carried on a lively correspondence, will repeat my pieces April 20 at Symphony Space in New York City; I’ll give details closer to the performance.Â

Opera You Can Afford

I’ve been so busy surviving until spring break that I forgot to mention that I’ll be on a panel today at 5 in advance of Elodie Lauten’s Two-Cent Opera tonight at Theater for a New City in New York (1st Ave. between 9th and 10th). We needed a Beggar’s Opera for the 21st Century and this sounds like it: a mystic meditation on jobs and money. It doesn’t quite sound like anything else she’s ever written, yet it’s still infused with that same Neptunian personality that enchanted me in The Death of Don Juan 25 years ago.Â

The Weightless Life

Now, just about every piece of music I’d ever consider teaching is stored on two external drives as mp3s, one drive at school and a duplicate at home. A lot of the music I teach is 18th- and 19th-century, and the bulk of that repertoire can be downloaded as scores on my desk computer from imslp.org. For 20th-century repertoire, I’ve scanned a lot of the music I teach regularly into PDFs, and I’ve traded PDF collections with faculty from other schools (I protect my sources), so I have hundreds of modern and postclassical scores on those hard drives as well. Now I carry no CDs or scores to school at all. It still feels strange to pick up my computer bag every morning with almost nothing but my laptop in it – like I’m going to work naked or something. With a touch more organization I could even leave that at home. If I start to play something and find it’s not on my hard drive (as happened recently when I tried to make an unanticipated foray into Giya Kancheli symphonies), I write myself a note and rip the CD to my computer when I get home. I can always make a class out of the 16,000 mp3s I’ve got with me (it’s a larger collection than Bard’s CD library). If I don’t own a piece I need, I can plug into the internet at school and play it from the Naxos music library service we subscribe to.Â

I save a lot of paper by projecting PDF scores from my computer onto a screen, rather than making individual copies for all the students. When I do need to copy something, I print a PDF and run it through the machine, rather than stand there laboriously turning the bound score over page after page. If I need to research something for class, say, find some repertoire for an assignment so obscure that students can’t look up the composer, I do it all on the internet rather than in the library, and spend many more hours at home than I used to. (Of course, students can take advantage, too. I am told of a grad student who was given a take-home test of anonymous pages from orchestral scores to identify as closely as possible by style. Seeing the publisher’s score number at the bottom of each page, he simply Googled each number and correctly identified every piece.)

My extensive PDF collection of 20th-century scores will make it sound like I’m one of the scofflaws responsible for the gradual death of music publishing, but not so. I used to go to Patelson’s in New York and buy whatever attractive modern scores they had, which were never many. Occasionally I would order something, but it almost never came. Now, I scour the internet for scores, and find obscure things Patelson’s would never carry. I’ve been buying more printed, commercial scores than ever, because the internet allows me to find what I need. (And believe me, I’ve done about as much to keep poor Patelson’s afloat as any mere academic could be expected to do.) Many of the PDFs I use for teaching are made from scores I paid for, and if I break copyright laws, it’s usually to get access to music that the music publishing companies somehow can’t manage to keep in circulation – often music that they’ll rent for performance, but won’t sell. Of course, almost all the postclassical scores I have were home-produced by the composer and never entered the commercial marketplace at any level. I get the music legally if possible, but I get it.

And though I seem a little ahead of the curve by musical standards, I’m a Luddite compared to some of my colleagues in other fields. They use something called Moodle that lets them store all their teaching materials on the internet, including letting students upload their papers, which the professor corrects on the browser and reposts. We’ve got professors who walk into class empty-handed, having everything on the computer, and never touch a piece of paper. Of course, for that, you need a “smart classroom” with a computer terminal, which we can’t seem to get in the music building (though I’m first in line every time they’re offered), and for wireless we musicians walk around the halls like we’re dowsing for water, trying to tap into the film department’s wireless next door. Also, our current Moodle system can’t quite accommodate the space-intensive audio files I need. (The year the library offered to put reserve recordings on the internet, my first and legitimate request was Der Ring des Nibelüngen. They balked.)

(Also, imslp, though I’m its biggest fan, is a work in progress. Aside from highly variable scanning quality, I recently downloaded Schumann’s Davidsbündlertanze only to find that imslp’s copy is labeled Davidsblündertanze – David’s Blunder Dances? - right on the music. I tried to leave a complaint, but couldn’t access any page at imslp to do so.)Â

But I’m astonished at how much less paper there is in my life, how much more time I spend at home, how much less time I waste searching for objects, how much less it matters where I am, and how many more materials I have access to anywhere I go. Not once this school year have I driven back home because I had forgotten something. Also, I used to, like many composers, show up at any performance with an extra copy of all the parts, just in case. Now all my parts are posted on my web site at non-public URLs. You want to perform a piece of mine, I’ll e-mail you the URL. When I fly around the world to lecture I upload my lecture and examples to the internet, and print them out when I get there, if not simply project them on a screen. I carry almost nothing.

Running Up Against the Past

Sarah Cahill’s premiere of my War Is Just a Racket last night was fabulous. The video her husband John Sanborn made to accompany my piece (which I hadn’t yet seen), was, I thought, with its footage of General Smedley Butler speaking and a dollar bill waving like a flag, the evening’s most apt and imaginative video, and I’m ready to package the music plus video as a multimedia piece. (It does require three screens, though, which will make the video impractical for general use.)Â

Another Jolt in the Paradigm Shift

Yesterday I received a check in the mail from Arts Journal, my first income from the ads over on the right side of your screen. Since 2003 I’ve now made nearly a quarter per entry for all my musings on this blog! – although, if you limit it to the last eight months that we’ve had ads (as I should), I’m really making just over $2 per entry. I’m going to call that pretty damn good for now, considering I started this without a thought of making any money at all.Â

Piano Music to Leave Iraq By

“We must see that peace represents a sweeter music, a cosmic melody that is far

superior to the discords of war,” said Martin Luther King in his Nobel Lecture. Pianist Sarah Cahill took the phrase “A Sweeter Music” for her project of 18 anti-war (or pro-peace) works that she’s premiering this year. I’m happy to say that one concert in that series will take place this Thursday evening, March 12, at 8 at Merkin Hall in New York City, and that it will include the world premiere of my War Is Just a Racket. It’s an odd piece for me, written for a pianist speaking a text while playing, and I hope it works. Sarah’s husband John Sanborn has made video to accompany all the pieces; you’ll recognize the name as the artist who does all of Bob Ashley’s video, and I’m honored to have a connection to his work. The concert is part of Jon Schaefer’s New Sounds Live series, so I guess you’ll be able to hear it on radio as well. The whole program is:

Preben Antonsen (b. 1991): Dar al-Harb: House of War

Kyle Gann (fl. 1440s): War Is Just a Racket

Frederic Rzewski: Peace Dances

Jerome Kitzke: There is a Field

Phil Kline: The Long Winter

The Residents: drum no fife: Why We Need War

Terry Riley: Be Kind to One Another (Rag)

So I’m Neo-Riemannian: Who Knew?

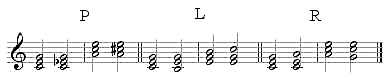

To teach undergraduate music theory is to recount over and over and over, year after year without variation, facts, terminology, and principles that haven’t changed since well before I was born. But Wednesday I managed to teach something new, and got a real kick out of it: Neo-Riemannian theory (named for the German musicologist Hugo Riemann, 1849-1919). I had never heard of the subject until the 2007 Minimalism conference in Wales, where Scott Alexander Cook applied the methodology to the music of Gavin Bryars (PDF). The idea is that relationships between triads can be characterized by variously close or distant pitch replacements, categorized by the three functions P (parallel), L (leading tone), and R (relative). The P function moves the third of a triad to change it from major to minor, or vice versa:

The L function lowers the root of a major triad a half-step, or raises the fifth of a minor triad a half-step, creating a new triad of the opposite modality in either case. The R function raises the fifth of a major triad a whole-step to produce the triad of the relative minor, or lowers the root of a minor triad a whole-step. And there are some other derived functions, such as D, which does from a triad to its dominant, or vice versa. And functions can be combined, so you get PL, RP, LPL, and so on. If I’m oversimplifying or getting it wrong, some kind reader will correct me.

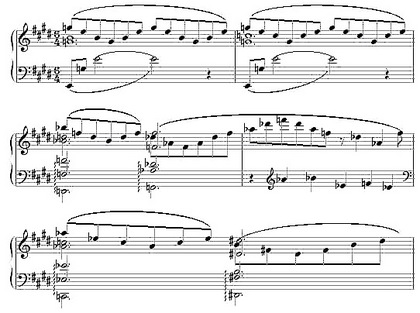

The occasion of my bringing this up was my biennial analysis of a gorgeous passage from Liszt’s Années de Pelerinage, the beginning of “Sposalizio,” which is hardly complicated, but notoriously recalcitrant to Roman numeral analysis:

Now instead of calling that i-VI in E minor and wondering where in hell the B-flat major came from, I could label the sequence L, RLRL (or DD, since C to B-flat is two dominant jumps), PR, D, PR. It doesn’t really explain the music – though the PR does make clear the equivalent jumps from B-flat to D-flat and A-flat to B, which the enharmonic pitch notation hides – it just gives me a way to label Liszt’s key jumps, more radical in their unconcern for tonality than Chopin’s or Schumann’s. And I think the students enjoyed learning a theoretical technique that wasn’t from the musty, immemorial past, but evolved during their lifetimes.

The even greater interest for me is the potential application to my own music. In 1983, I switched over, with some trepidation, to writing in a triadic style, though not at all functionally tonal. I had been studying Bruckner and taking tips from passages like this wonderful one from his Eighth Symphony:

(Interestingly, in the immediate repeat of this passage Bruckner replaces the RP with a PR, and ends up in D major instead of A-flat.) I soon found myself rather obsessed with what I now learn are called LPL and RPR transformations (the latter yielding a tritone transposition). Here’s Baptism, from 1983:

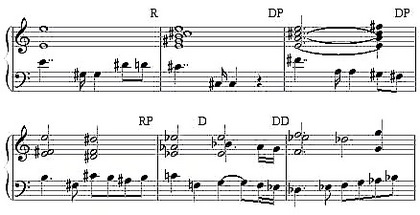

The chord changes, if I have parsed them correctly with my amateur notions of Neo-Riemannian terminology, are PLP, RPR, LPL, RPR, LPL, LPL, RPRP, LPL. Note that no chord change requires fewer than three transformations – that was my conscious discipline for the piece, but of course I wasn’t thinking of it in Neo-Riemannian terms, which hadn’t been invented yet. This was pretty much my default harmonic language from Baptism of 1983 to my “Last Chance” Sonata of 1999. In 2000 I studied jazz harmony with John Esposito, and switched over to bebop chords. My microtonal music uses a process of micro-interval voice-leading that Harry Partch called “Tonality Flux,” related to Neo-Riemannian transformations, but of course not reducible to them. However, the large-scale tonal structure of my 2002 microtonal chamber opera Cinderella’s Bad Magic consists of a chain of simple Riemannian pitch shifts, all tuned to pure triads and evolving from E-flat major to C double-sharp minor, through single note-shifts R P R P L P R P L:Â

These Neo-Riemannian labels neither explain nor justify my music, but they do give me simple ways to refer to my voice-leading methods as classes of harmonic transforms. And, as papers at the last minimalism conference proved, Gavin Bryars and John Adams were using a similar kind of non-functional harmonic consistency from the early 1980s on as well. This terminology can make it easier to point out how the harmonic practices of Liszt, Bruckner, and Reger returned, following the period of widespread atonality, to form a new common practice in minimalist and especially postminimalist music – starting, I think we’d have to say, with Einstein on the Beach, whose “Spaceship” scene may succumb to only this kind of analysis. Neo-Riemannian theory may fill in some cracks in our analysis of Romantic music, when dealing with composers who couldn’t abide within the Germanic idea of a centralized tonality. For postminimalism, it may prove to be the analytical technique that fits the music like a glove.