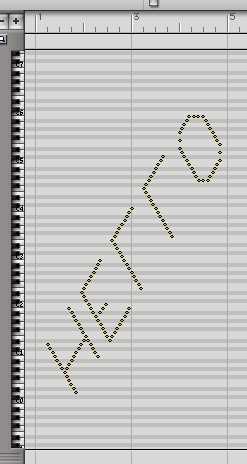

Draw a straight line and follow it.

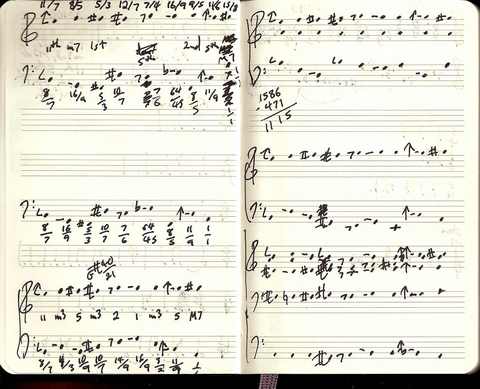

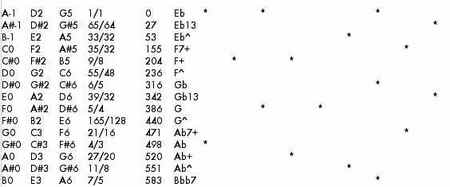

Apparently I’ve just broken copyright law. I can’t believe what’s holding up my Cage book: you are no longer allowed to quote texts that are entire pieces of art. This means I’ve been trying to get permission simply to refer to Fluxus pieces like La Monte Young’s “This piece is little whirlpools in the middle of the ocean,” and Yoko Ono’s “Listen to the sound of the earth turning.” And of course, Yoko (whom I used to know) isn’t responding, and La Monte is imposing so many requirements and restrictions that I would have to add a new chapter to the book, and so in frustration well past the eleventh hour, I’ve excised the pieces from the text.Â