Well, the idea of a conference being blogged daily by the co-director of same conference has pretty much been derailed. I’ll have to wrap it up when I get back. Let me leave you for now with another group photo, taken remotely by Scott Unrein on the roof of his apartment building. This followed Sarah Cahill’s absolutely dynamite recital, in which the revival of Harold Budd’s Children on the Hill rang out perfectly; as Scott said, close your eyes and that was Budd up there playing. Sarah closed with Terry Riley’s sophisticatedly jaunty “Be Kind to One Another” Rag – another improvised piece, which Terry wrote down after improvising it for Sarah to play. Here we are – Charlemagne Palestine, Sarah, me, Kerry O’Brien, Scott and his wife Judy, David McIntire and his wife Michelle, Andrew Granade, Galen Brown, Andy Lee, Jedd Schneider, Andy Bliss, Sumanth Gopinath, Rachel McIntire, and Kansas City:

Political Interlude

Here in Missouri I saw a car festooned with the most virulent anti-Obama bumper stickers, plus one that read: “I’ll be as gracious to your president as you were to mine.” That settles something I’d wondered about: a lot of the anti-Obama vitriol, I feel certain, is little more than revenge for decent peoples’ justified anger over things W. Bush actually did, and for the Right’s embarrassment for having supported a moron, while we have a nice, well-spoken, dignified president.

Narayana’s Cows with the Perfect Sauce

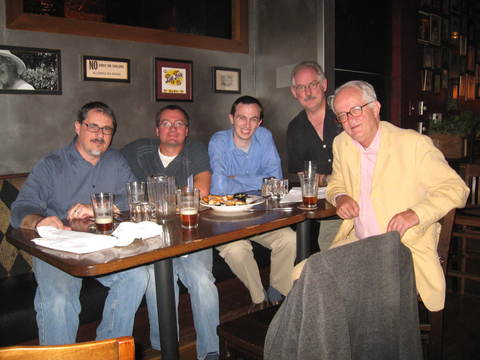

The big minimalist event today was maximalist indeed – a celebrity dinner party at Arthur Bryant’s, just about the most famous barbecue place in the world. The photo below just postdated Mikel Rouse’s departure, but still we had Rachel McIntire (David’s daughter, video-documenting the conference); composers Paul Epstein, Charlemagne Palestine, and Scott Unrein; pianist Sarah Cahill; and musicologists Keith Potter, Dragana Stojanovic-Novicic, and Pwyll ap Sion:Â

Watching History Turn on a Dime

What an amazing first day of the 2nd International Conference on Minimalist Music. Maarten Bierens from Belgium demonstrated how Louis Andriessen’s subtly subversive use of quotations gave his music a dialectical significance quite foreign to American minimalism; Pwyll ap Sion detailed the amazing range of self-quotation in Michael Nyman’s output. But what blew me away were three papers on Phill Niblock by Keith Potter, Richard Glover, and Rich Housh, who had gotten access to Phill’s files and could exhibit the varied ways he shapes his slowly moving drones. Apparently, Phill’s music has taken on a new life since he started working directly in ProTools, which gives him greater control over the out-of-tuneness of his pitch clusters. As UMKC musicologist Andrew Granade remarked to me, we’ve each known maybe three people in academia before now who had even heard of Niblock, and suddenly the room was full of Niblock aficionados, shouting answers to each other’s questions and deconstructing his music as matter-of-factly as if it was Mahler and we all had the Kalmus scores. Suddenly, “drone minimalism” is a topic that can hold its own against repetitive minimalism, as though it had been all along. What a feeling, sitting there and watching the official history of music reel, switch trajectory, and transform itself around you!

D-Day Minus One

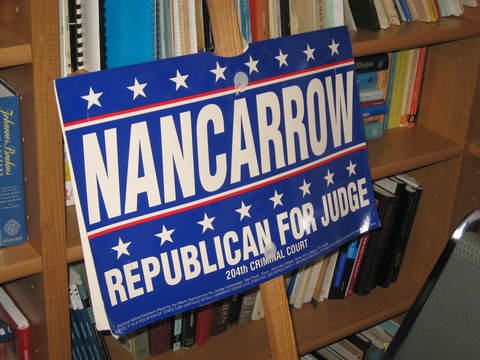

David McIntire and I had been wanting to visit the grave of Virgil Thomson, and came up with a minimalism conference as the simplest way to create the opportunity. So early this morning four of us headed off for Slater, Missouri (pop. 2083), the town Thomson was born in. Only we found the town more willing to take credit for a different favorite son:

D-Day Minus Two

Kansas City ain’t Wales, but it has its impressive features:

“…radically accessible…”

The Kansas City Star previews our minimalism conference.Â

November Already

I am not the first person to play through Dennis Johnson’s November, but on August 12 I became apparently the first person to listen to an entire recording of it. You can be the second. In honor of the sixth anniversary of this blog tomorrow (Saturday), among other things, I have uploaded a complete performance of November, one of the earliest (1959) major minimalist works. The first public performance of the piece since the early ’60s at least will take place in Kansas City on September 6, with myself and Sarah Cahill alternating at the keyboard. I have recorded a version of the entire work here, conveniently formatted in four parts [UPDATE: I have replaced my private recording with the one Sarah Cahill and I made at the Second International Conference on Minimalist Music, Sept. 6, 2009, so the next paragraph no longer applies]:

Part 1Â 1:03:09

Part 2Â 1:13:48

Part 3Â 1:06:54

Part 4Â 1:05:19

It’s not a professional-level recording, though I made it on my wonderful Sony PCM D-50, which has totally changed my life. I had to switch pianos at one point, because the freshmen arrived at Bard halfway through, and the piano I started on was in a room where high heels clicking through the hallways were too audible (and those were the guys!). But it’s the first complete recording, with all the material contained in the score. It lasts only four hours, and I think I could have gone longer, but every note you hear is in the score, and there is virtually nothing omitted.

Dennis’s surviving recording contained only the first 112 minutes of the piece. What I am playing is an exact transcription of those 112 minutes, as identical to the original as I could make it, and then I improvise the remainder of the piece according to rules I obtained by analyzing the relationship of the recording to the score. The reason for sticking to the transcription for the first 112 minutes is that there are aspects of the piece not ascertainable from the score; the score was derived from the original tape rather than the other way around, and Dennis’s letter to me about it stated that “the recording must stand as the primary definition example of the piece.” Subsequent performances need not be so slavishly faithful to the recording, but this first exposure has got to get the piece across as Dennis played it, so musicologists can know exactly what they’re dealing with. Before you go there, the idea of this piece from the beginning was that it is a (loosely) notated piece, that any so-minded pianist could play it with complete authenticity. Dennis was not a great jazz pianist, not a jazz pianist at all in fact, and there is nothing technical nor idiosyncratic about his playing that another pianist couldn’t sufficiently imitate. Dennis is flattered that Sarah Cahill and I are doing this, just as Harold Budd is flattered that Sarah is playing Children on the Hill. If the composers are thrilled, you have no theoretical basis on which to disapprove.Â

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

There is a hilarious sequence of situations in Mark Twain’s Innocents Abroad in which Twain and his fellow tourists drive an Italian tour guide to absolute distraction with questions of surreal incomprehension:

Our guide there fidgeted about as if he had swallowed a spring mattress. He was full of animation – full of impatience. He said:

“Come wis me, genteelmen! – come! I show you ze letter writing by Christopher Colombo! – write it himself! – write it wis his own hand! – come!”

He took us to the municipal palace. After much impressive fumbling of keys and opening of locks, the stained and aged document was spread before us. The guide’s eyes sparkled. He danced about us and tapped the parchment with his finger:

“What I tell you, genteelmen! Is it not so? See! handwriting Christopher Colombo!–write it himself!”

We looked indifferent – unconcerned. The doctor examined the document very deliberately, during a painful pause. – Then he said, without any show of interest:

“Ah – Ferguson – what – what did you say was the name of the party who wrote this?”

“Christopher Colombo! ze great Christopher Colombo!”

Another deliberate examination.

“He write it himself! – Christopher Colombo! He’s own hand-writing, write by himself!”

Then the doctor laid the document down and said:

“Why, I have seen boys in America only fourteen years old that could write better than that.”Â

“But zis is ze great Christo- ”

“I don’t care who it is! It’s the worst writing I ever saw. Now you musn’t think you can impose on us because we are strangers. We are not fools, by a good deal. If you have got any specimens of penmanship of real merit, trot them out! – and if you haven’t, drive on!”

Half of the comments I got on my recent Harold Budd posting, several of them by people criticizing me while admitting that they hadn’t listened to the music they were criticizing me for, were about on this level. It’s not as funny from the tour guide’s perspective. I’m offering you the minimalist equivalent of Christopher Columbus’s handwriting, neither for your critique nor for your approval, but because I have the information, I enjoy disseminating it, and I know there are people interested. The claims I make for this music are that the tape said the piece dated from 1959 and the performance from 1962, and that La Monte told me that this piece inspired The Well-Tuned Piano. If you have evidence to confute these claims, I’ll be curious to hear it; otherwise, criticizing me for this reveals a misunderstanding of the situation. This is musicology, not American Idol. If this recording or the piece isn’t your cup of tea, that’s OK, I understand, but I can’t alter the results of my research to suit your squeamish and waffling tastes. If you want your comment posted – respond appropriately.Â

Great Moments in Music History

Minimalists Prepare for Counterattack

I have been too busy to give timely notice to the nice attention that Galen Brown (whose paper on minimalist means and ends will be featured) has given to our minimalism conference over at Sequenza 21 via an interview with me, in my usual punchy style.

Right Name, Wrong Campaign

This Budd’s for You

OK. The night was Friday, July 9, 1982. I was administrative assistant for the New Music America festival in Chicago. I had a big argument with my then-girlfriend (whom I later married nevertheless) which turned out, surprisingly enough, to be all my fault. In a huff brought on by my inability to invent a benign rationale for my behavior convincing enough to satisfy even myself, I sulked out and vowed to walk from our apartment to the festival. As the distance was something under three miles, I had an hour to make it in, and it was a mild summer day, this was a less self-punishing exercise than it may sound. As I trudged up to Navy Pier, Harold Budd had just started playing the performance of his piece Children on the Hill that you can hear here. I stood in one of Navy Pier’s huge doorways simply transfixed. Rarely in my life have I heard another performance so lovely from beginning to end. Navy Pier is enormous, the crowd was huge and casual, and I have always been chagrined about the baby who wails like a banshee at many points during the recording.Â

For many years I have toyed with the idea of transcribing this wonderful recording, but given the speed of Budd’s cascading arpeggios in the 13-minute middle section, I doubted the feasibility until digital software rendered it possible to slow it waaaaay down (sometimes to 1/5th-speed) without changing the pitch, EQ-ing it to bring out selective registers. It’s taken dozens of hours of ear-stretching work over the last two years, but I’ve done it, and the amazing Sarah Cahill will finally recreate this performance at Kansas City on Friday, Sept. 4, at the Second International Conference on Minimalist Music. It’s the most difficult musicological feat I’ve ever attempted. The Well-Tuned Piano was child’s play by comparison.

You may (and should) be familiar with the five-minute version of Children on the Hill on Budd’s 1981 recording The Serpent (in Quicksilver) on the Cantil label, rereleased in 1992 on All Saints. That version never changes key or tempo, nor deviates from a B-major scale. This version is recognizably similar in motive and atmosphere, but enormously more complex. The main motive on the Cantil version is B-D#-E; here it is inverted, D#-E-G#. The opening section is based in B major, but abruptly shifts to D, C, and C#. The rapturous middle section, a torrent of Budd’s trademark major-seventh chords, alternates at first between E and Db, but moves upward though D and Eb to an alternation of F and Gb before finally settling back to C# for the ending recapitulation. At no time does the key jump more than a minor third away. Interestingly, each key is associated with a particular textural configuration, so that every return of a key is also the return of a type of arpeggio and melody. Often transitions between keys are introduced by the right hand entering the new key first, so that the left hand resolves a poignant moment of bitonal dissonance. Budd says that he would sometimes use written-down motives on a scrap of paper as a guide, but that these notations are long gone. And, looking at my transcription, he wrote, “I couldn’t play that in a thousand years.”

Below I post my transcription of the segment from 10:30 to 11:32 on the recording. My rhythms are pretty conjectural, often simply an attempt to get all the notes in the right order. The fact that the piano is run through a harmonizer added to the difficulty. Sarah’s working hard, though, and practicing along with the recording to get the unnotatable nuances of rhythm and pacing. I am thrilled that I’m finally going to get to hear this music live again, and get a recording without the crying baby. That kid must be 27 now, and in Kansas City bouncers will be on the lookout for a suspicious 27-year-old.

Comments closed. I thought this Budd was for you, but I guess it was for someone else.