Someone has finally come up with an easily retunable piano. Looks (and sounds) a little more like a clavichord, actually, and while I’m pleased about the retuning, each string appears to have only about a whole tone’s leeway. You’re still more or less limited to 12 pitches to the octave, but there’s a lot you can do with that: not only meantone and other historical temperaments, but the tunings of most of the standard pieces for retuned piano: Ben Johnston’s Suite for Microtonal Piano, The Well-Tuned Piano, The Harp of New Albion, and so on. It’s presumably far more affordable than the piano Trimpin once designed for me on a napkin, which could be automatically retuned via computer while you played. They’ll have a whole world of microtonal acoustic instruments invented by the time I’m too old to lift a pen to write for them. (h/t to McLaren)

Someone has finally come up with an easily retunable piano. Looks (and sounds) a little more like a clavichord, actually, and while I’m pleased about the retuning, each string appears to have only about a whole tone’s leeway. You’re still more or less limited to 12 pitches to the octave, but there’s a lot you can do with that: not only meantone and other historical temperaments, but the tunings of most of the standard pieces for retuned piano: Ben Johnston’s Suite for Microtonal Piano, The Well-Tuned Piano, The Harp of New Albion, and so on. It’s presumably far more affordable than the piano Trimpin once designed for me on a napkin, which could be automatically retuned via computer while you played. They’ll have a whole world of microtonal acoustic instruments invented by the time I’m too old to lift a pen to write for them. (h/t to McLaren)

Kierkegaard, Strolling through Toronto

Keeping Good Company

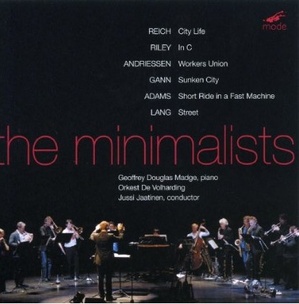

I had expected to have two new CDs and a book out this fall, but two of them have been delayed until February. One of the CDs, however, has arrived, titled The Minimalists, by the Orkest de Volharding on Mode Records (Mode 214/5). It’s a two-CD set, and the lineup consists of:

I had expected to have two new CDs and a book out this fall, but two of them have been delayed until February. One of the CDs, however, has arrived, titled The Minimalists, by the Orkest de Volharding on Mode Records (Mode 214/5). It’s a two-CD set, and the lineup consists of:

Steve Reich: City Life

Terry Riley: In C

Louis Andriessen: Worker’s Union

Kyle Gann: Sunken City

John (Coolidge) Adams: Short Ride in a Fast Machine

David Lang: Street

Maryanne Amacher (1943-2009)

[For emendation to the above dates, see updates below.] The music world lost one of its most bizarre characters today, and I say that with the utmost affection. Maryanne Amacher was an amazing composer of sound installations, who occasionally taught courses at Bard. I first encountered her in 1980 at New Music America in Minneapolis. She had, as was her wont, fitted an entire house with loudspeakers, and the staff was in a state of jitters because at opening time she was still obsessively running around and changing things. She was a tireless perfectionist. Years later I interviewed her for my history of American music. A Stockhausen student, she was absolutely inscrutable, so intuitive that pinning facts down was an insult to her spirit. My first ten questions having elicited no specific information, I finally asked whether her original sound sources were acoustic or electronic in origin. Her perplexed answer: “I really can’t say.” She was vagueness personified. Yet she was an incredible artist, and my son thought she was the best electronic music teacher Bard had. She typically wore bright red overalls and aviator goggles, and I’d be astonished if her wiry frame weighed 90 pounds. After one semester with her, one of my colleagues – an artistic and sympathetic soul, but I understood his frustration – said, “I feel like I’m on the set of You’re a Good Man, Charlie Brown.” She lived in a huge old house in Kingston that was cluttered wall to wall with papers, tapes, and technical equipment, among which one walked gingerly through narrow paths. You closed doors carefully, too, for fear the entire soggy house would fall down. But she was some kind of genius, and her spatially intricate sound installations, better appreciated in Europe than here, had to be heard live: there is no way to adequately document them on recording. As with La Monte Young, you felt that her ears were picking up things yours couldn’t. She lived for her art. I heard a few weeks ago that she’d had a stroke, then from Pauline Oliveros that she was in a nursing home, and today she passed away. I do hope her work is well documented, because it is absolutely inimitable. We will never hear her like again.

[For emendation to the above dates, see updates below.] The music world lost one of its most bizarre characters today, and I say that with the utmost affection. Maryanne Amacher was an amazing composer of sound installations, who occasionally taught courses at Bard. I first encountered her in 1980 at New Music America in Minneapolis. She had, as was her wont, fitted an entire house with loudspeakers, and the staff was in a state of jitters because at opening time she was still obsessively running around and changing things. She was a tireless perfectionist. Years later I interviewed her for my history of American music. A Stockhausen student, she was absolutely inscrutable, so intuitive that pinning facts down was an insult to her spirit. My first ten questions having elicited no specific information, I finally asked whether her original sound sources were acoustic or electronic in origin. Her perplexed answer: “I really can’t say.” She was vagueness personified. Yet she was an incredible artist, and my son thought she was the best electronic music teacher Bard had. She typically wore bright red overalls and aviator goggles, and I’d be astonished if her wiry frame weighed 90 pounds. After one semester with her, one of my colleagues – an artistic and sympathetic soul, but I understood his frustration – said, “I feel like I’m on the set of You’re a Good Man, Charlie Brown.” She lived in a huge old house in Kingston that was cluttered wall to wall with papers, tapes, and technical equipment, among which one walked gingerly through narrow paths. You closed doors carefully, too, for fear the entire soggy house would fall down. But she was some kind of genius, and her spatially intricate sound installations, better appreciated in Europe than here, had to be heard live: there is no way to adequately document them on recording. As with La Monte Young, you felt that her ears were picking up things yours couldn’t. She lived for her art. I heard a few weeks ago that she’d had a stroke, then from Pauline Oliveros that she was in a nursing home, and today she passed away. I do hope her work is well documented, because it is absolutely inimitable. We will never hear her like again.

Total Heaviosity

Silence and Noise

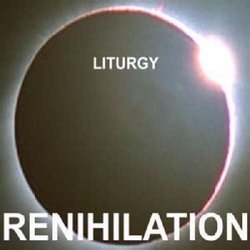

This Friday night, Oct. 16, my son’s black metal band Liturgy plays at the New Yorker festival, at the Bell House in Brooklyn, 149 7th Street, 8 PM. The event is listed as already sold out, but I’m supposed to be on a guest list. I just heard the band play live on WFMU. Their new CD Renihilation is out on the 20 Buck Spin label. It’s ecstatic, in a loud and rhythmically propulsive sort of way. Even my former newspaper seems to think they’re a strange but inspired choice for the festival. Not sure what that means, except that maybe it took my son 16 months out of college to get more famous than I am.

This Friday night, Oct. 16, my son’s black metal band Liturgy plays at the New Yorker festival, at the Bell House in Brooklyn, 149 7th Street, 8 PM. The event is listed as already sold out, but I’m supposed to be on a guest list. I just heard the band play live on WFMU. Their new CD Renihilation is out on the 20 Buck Spin label. It’s ecstatic, in a loud and rhythmically propulsive sort of way. Even my former newspaper seems to think they’re a strange but inspired choice for the festival. Not sure what that means, except that maybe it took my son 16 months out of college to get more famous than I am.

Over the course of his long life, silence meant many different things to John Cage: an act of cultural humility, a respite from corporate Muzak, a structural space to be filled by sounds, a religious observance, a release from the ego, an equivalent to Zen meditation, a communion with nature. This paper traces the evolution of the concept of silence through Cage’s biography, with special reference to the complicated evolution of ideas that led to his famous noteless (but hardly silent) sonata 4’33”.Â

Upcoming Appearances

Several performances of my music, or in which I am involved, are coming up. First of all, percussionist Andy Bliss will play my vibraphone piece Olana on a concert in Chicago this Sunday, Oct. 4, at the Chicago Temple, 77 Washington Street, at 2 PM. The concert, a duo with pianist Mabel Kwan, also includes pieces by John Luther Adams, Julia Wolfe, Eve Beglarian, Alvin Singleton, and others – looks like a great lineup.

Unintended Consequences

A Slope of Rugrats

Lord, am I enjoying wallowing in this wonderful recording of Sarah Cahill playing my transcription of Harold Budd’s Children on the Hill from a few weeks ago at the Second International Minimalism Conference. Near the end of the fast part, every key change could signal a return to the A section, and every one that doesn’t is a heartbreaking reassurance that the heaven of the piece isn’t about to end yet.Â

The Things You Can Steal from Students

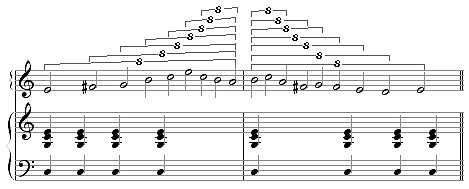

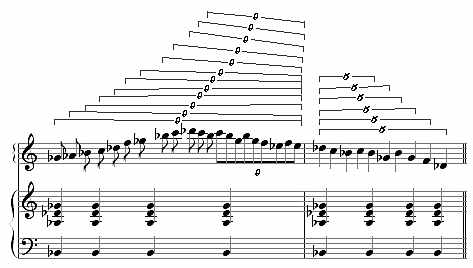

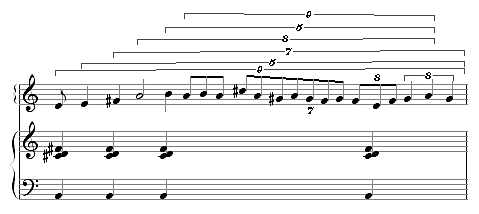

As you may know, I love using Sibelius to generate wacky rhythms, but one of my students, Ben Raker, showed me some in a piece of his today (50 minutes long!) that I’d never tried. For some reason I’ve generally shied away from tuplets-within-tuplets, but Ben had come up (accidentally, he admitted, by punching the tuplet button twice instead of once) with a scheme for a quasi-irrational but actually elegantly geometric acceleration and ritard:

The Outside-One’s-Ism Student

In comments, Ernest asks (and I’d rather address this than the article I’m supposed to be writing today):

I was always

curious about what a student could do if their professors genuinely dislike the

music they create. It seems like a giant imposition on the student to alter his

style just to fit his or her teacher’s expectation of good music. Is this at

least expected of the student in so far as the course is concerned? I don’t

want to seem like I think this is the norm, but there has to have been

overzealous teachers who try to discourage them into writing more traditional

pieces, right?

Others will undoubtedly want to weigh in on this. I want to say I’ve never disliked a work by one of my students, though I have to admit it’s not quite true. I’ve rarely completely liked one, either. When you watch a piece grow from its first inchoate ideas to some sort of performable score, you get, I think, more caught up with the process than the result. This is a strange and mysterious process with two egos involved, and your own is not the important one. I would never, ever tell a student that the overall effect he or she wants to create is of no value. I always feel most satisfied when I can pinpoint localized things in the piece that I think injure the whole shape or progress of the piece, and the student, in response, ignores my proposed solutions but takes the criticism seriously and comes up with his or her own revisions instead. That satisfies my sense of having made a difference, and the student’s sense of having come up with every note. And to this extent, liking or disliking the piece, or its style, is beside the point. It may be a little like asking a gynecologist whether his last patient was pretty.Â

That said, in my situation, I’m the number 2 or 3 composition teacher at Bard, and so any sensible student who’s going to write music in a style I don’t care for is much better off studying with Joan Tower, whose tastes are the diametric opposite of mine and who can do much more for him professionally after graduation than I can. Joan seems to send me the students she gets whose music is “too tonal” or too deliberately uneventful. This is why I think it’s so crucial that a music department aim for diversity of viewpoint among its faculty, which many refuse to do. I think to find an idiom that neither Joan, George Tsontakis, nor I would be sympathetic to, you’d pretty much have to be a staunch Ferneyhough acolyte, which is not common among undergrads. It’s rare, in fact, for our undergrad composers to have much sense of style at all – their music is more often made up (as mine was at that age) of bits of this and that: a harmony they liked in Steve Reich, a melodic tic from George Crumb, some glissandos they heard in Penderecki. Now, I’ve never taught graduate composition students, and the few who’ve brought me their music have done so, as you can imagine, because it’s in a style that they think is right up my alley (often coming to me because their own professors weren’t sympathetic). If an accomplished 24-year-old composer brought me music conditioned by her passionate admiration of, say, Chris Rouse or Harrison Birtwistle, I’d have a quandary I haven’t faced yet. I’ve never regretted teaching in an undergrad-only institution.

But when I haven’t much liked hearing a piece by one of my students, it’s usually with a feeling that “This student isn’t much interested in the same things I am” – which is fine, because few of them are. And of course I would never grade them downward for that, because all that interests me grade-wise is how much work they put in – and that work can even be a lot of serious thinking and sketching, with little actual music to show for it. One of the smartest students I ever had used to analyze scores by prize-winning young composers and try to imitate them – certainly not a route I encouraged, but I watched him with amusement and added what suggestions I could. I gather that, in grad school, he eventually found that a dead end, but it wasn’t in his interests for me to predict that. My teaching motto is from Blake: “If the fool would persist in his folly, he would become wise.”

There are a lot of composers who feel that a student should try out every composition teacher in the department to get a variety of viewpoints, but I was never very sympathetic to that. Some of our students do it, and if they go back to Joan or George (or our excellent jazz composition teacher Erica Lindsay) I wish them well and continue to take an interest in their progress. I was the type of young composer who would not have benefitted from a stylistically adversarial relationship – and didn’t, the couple of times it happened. (I had one abominable professor who acted so insulted when I suggested trying another teacher that I was afraid to switch. He was a horse’s ass, and should have been fired, but instead made students miserable for several decades.) But I do think that the type of composition teacher who insists on the student writing in his or her own style  – not nearly as common as they used to be in the ’60s and ’70s, apparently – is very much to be regretted, and I think most composers of my generation have realized the harmful effects of that. Anyone disagree?

And to return the original question to its original context in connection with the minimalism conference: if the musicologists at Bard wanted to hold a serialism or Spectralism conference, or one on the New Romanticism or New Complexity, I would find that interesting rather than threatening, and would probably attend some of it with a curious attitude. My compositional motto comes from Satie: “Show me something new, and I’ll start all over again.”

Already Against the Next War

Sarah Cahill has finally given me a recording of my political piece War Is Just a Racket, which she premiered last March, and I’ve posted it to my web site. The program notes, detailing the text by General Smedley Butler and context, are here. Sarah does a beautiful job, as always.

The Minimalist Alliance

As my co-director David McIntire so aptly said in his opening remarks to the Second International Conference on Minimalist Music, minimalist music has always stressed community – not only in its unison-rhythmed, non-soloistic ensemble style, nor in its tendency to bring an audience together in a kind of mass ecstasy, but in the collective enthusiasm it kindles among its devotees. This was evident in the first conference in 2007, and became even more apparent last week in Kansas City. That group of us who attended both conferences – myself, David, Keith Potter, John Pymm, Pwyll ap Sion, Maarten Bierens, Tim Johnson – developed a deeper sense of camaraderie and common purpose. Those who regretted missing the first conference and loved this one filled us out into a larger circle. The excitement that followed Sarah Cahill’s fabulous recital, Charlemagne Palestine’s transcendent organ performance, and some of the more thought-provoking papers quickly communicated itself from person to person. Everyone seemed in an excellent mood all week, and in a more ebullient mood from day to day. The best minimalist music does not inspire cautious appraisal or cold analysis, but wide-eyed wonder. Those of us who love it found ourselves at home in Kansas City, and among kindred spirits.

I shouldn’t go too far in complimenting elements of a conference I helped plan, but I will make a few evaluative comments that hopefully won’t reflect on myself. Sarah’s elegantly flowing performance of Harold Budd’s Children on the Hill proved to my satisfaction that a transcription of the piece can be played in a spirit virtually indistinguishable from Budd’s own. I’ll post the recording as soon as I get it. She also reminded me of what a gorgeous piece Meredith Monk’s St. Petersburg Waltz is, and she introduced quite a few participants who hadn’t heard of it to Hans Otte’s scintillating The Book of Sounds, creating quite a stir for the piece.

No quantity of listening to Charlemagne Palestine CDs could have prepared one for the mammoth presence of his organ performance Schlingen-Blängen, a piece he first played in 1965 but had never played in the U.S. before outside Los Angeles. (In fact he’d never visited the Midwest before.) As we entered Grace and Holy Trinity Cathedral, a perfect fifth was already ringing on the organ. Little by little Charlemagne added notes, held down with little wooden splints, and pulled out additional organ stops to thicken the roar of sound. Finally he plunged onto the keyboard with both forearms, and, with overtones at maximum ferment – pulled the plug. The sound died in a swooping glissando, came back on, and did so twice more, in a powerfully dramatic effect. There was an audible bass line running through much of the piece, and after the organ finally died away for the last time, Charlemagne rang a drone on the rim of a cognac glass and sang the bass line in falsetto – it was the final ostinato melody from Stravinsky’s Firebird, not recognizable as such in the melee of drones. Here are Scott Unrein’s photos of the church as it looked to us, with the organ in the background and Tom Johnson’s ghost arising from the time exposure:

and Scott’s portrait of Charlemagne in action:

Despite his recent book on Terry Riley’s In C, Robert Carl’s own music is not noticeably postminimalist, and so he may have seemed like an odd choice for keynote speaker, but he was pitch-perfect. He first dismissed the facile platitude that minimalism might have been nature’s way of clearing the decks from serialism and making it possible to return to the relative “normalcy” of orchestral music like that of John Adams; instead, he said (and I’m paraphrasing from memory after a hectic teaching week), the radicalness of early minimalism was no mere aberration but a continuing and essential feature of the style. He then went on, as only an outsider to the movement could have, to detail what he thought minimalism had contributed to early 21st-century music in terms of flow and transparency. It was a moving tribute, and I told Robert afterward how much better he does public sincerity than I do.

As I’ve said, I had hoped that the conference would bring about some potent distinctions between minimalism and postminimalism. Galen Brown’s brilliant paper “Process as Means and End in Minimalist and Postminimalist Music” achieved a climax in that respect, widely noted as such. For Galen, minimalist music cared about process as a means regardless of what the sonic result was; postminimalist music uses process only to the extent that it achieves the sound the composer hears in his head. It was an admirably clear formulation, and I haven’t yet found a loophole in it. That paper, along with two others by Kevin Lewis and Andy Bliss, provided a remarkably rounded view of David Lang’s aesthetic, showing how willing he is to derive materials from processes that the listener can’t necessarily hear, yet disrupts his own processes sporadically to make his music more human. Scott Unrein drew out the sensitive subjectivity in Jim Fox’s music, and introduced that name to many present.

I’m disappointed that we didn’t get any of composer Paul Epstein’s music on the concerts, but his paper gave an absorbing account of the compositional structures he’s derived in the technique called “interleaving” that he took from Reich’s Piano Phase, which he’s developed into a surprisingly wide-ranging postminimalist technique. A paraphrase of his paper could make an entire chapter in this Music After Minimalism book I’m allegedly working on. Sumanth Gopinath and Gretchen Horlacher offered analyses of, respectively, Reich’s Different Trains and Tehillim that made me realize that my listening to Reich has become one-dimensional, as though I only hear what I’ve already come to expect. Sumanth in particular drew resemblances to tropes from various popular musics, and made me hear the music anew.

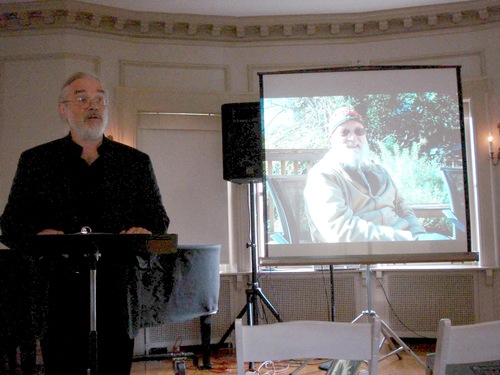

As for Dennis Johnson’s November, which Sarah and I gave the world re-premiere of, our rendition took four and a half hours, switching pianists every hour. The experience showed me a few things I still want to refine in my version of the piece. Luckily Sarah got the more melodic sections and made them heavenly. I realized that my own rusty piano technique was barely adequate even at November‘s leisurely tempo, but afterward Neely Bruce – a dynamite pianist himself – described my playing to me in detail in a way that made me feel good about it. I certainly loved doing it, and it’s the first time since the mid-1980s that I’ve performed, in a professional setting, anyone’s music except my own. Several conference participants had to leave to catch planes during the interim, but the 19 who managed to hang on to the end gave us a standing ovation, which in my case I took more as a compliment to my hard work and endurance than to my pianism. (Photo by Robert Carl)

I got home Tuesday at 1 AM and faced an eager Renaissance counterpoint class nine hours later. My luggage followed on Wednesday afternoon.

Per our group deliberations, the Third International Conference on Minimalist Music will take place – [drum roll, please] – in mid-October of 2011 at the University of Leuven in Belgium, a medieval university town 15 minutes from Brussels by train, under the leadership of Maarten Bierens. I already can’t wait. There was copious discussion of what institution in the U.S. might pick up the Fourth conference in 2013, but the story in every case was the same: at each representative’s school we considered, the musicology faculty would welcome the opportunity, but the resident composition professors would shout it down. That UMKC showed us such hospitality has made it one of the handful of schools I now recommend my student composers to consider for graduate studies. Musicology is the field through which minimalism is making its way into academia, and it is remarkable how many young minimalist-oriented composers, several of them in attendance in Kansas City, are getting their degrees in musicology as a way of bypassing the hidebound stodginess of the academic composing world. This conference is a confederacy of (mostly) young composers and musicologists allied to break the grip of modernism’s stranglehold on American academic composition departments. Our success in that venture is only a matter of time. God bless the musicologists for their exuberantly erudite support.

UPDATE: Pardon me, but I like this photo of me, by Robert Carl, explaining November: