A former student reports meeting a young Southern belle in North Carolina, mentioning John Cage to her, and having her respond, “Oh, didn’t he write some kind of opera about Sitting Bull?”  I’m going to speculate she was a student at Lenoir-Rhyne College when I performed Custer down there about eight years ago. Of course, what’s important about a name is how many letters it has, so, John Cage, Kyle Gann, Carl Orff, Arvo Pärt, Alex Ross, whatever. I wrote The Planets so people would mistakenly buy my CD thinking it was Holst, but I’m equally flattered to be confused with Cage. (But Senator – I knew John Cage, and I’m no John Cage.)

Regarding Ben

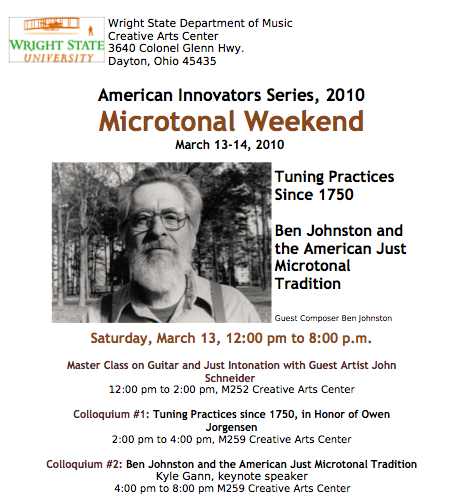

You can’t make a living giving keynote addresses, but through repetition you can become proficient enough at them to take them in stride. Here’s my keynote address honoring my teacher Ben Johnston, for the Microtonal Weekend at Wright State University, organized by composer and microtonal cellist Franklin Cox:

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Charles Ives once fantasized about “some century to come, when the school children will

whistle popular tunes in quarter-tones.” It has long seemed to me that when I hear people whistling popular tunes, quarter-tones are indeed often involved, but I think what Ives had in mind was that the popular tunes would be written in intentional quarter-tones. I don’t think this is likely to happen in my lifetime, but I do think that, thanks to several other important composers, Ben Johnston chief among them, the time may soon come when musicians feel free to hit the occasional seventh or even eleventh harmonic in their music, vernacular and otherwise.

I love listening to quarter-tone and sixth-tone music. It instantly puts you into a world in which our habitual musical categories fall apart. You lose the moorings that every musician gets trained into, and the rational part of your brain, the part that can analyze and identify what we hear, gets

short-circuited, and has to surrender to pure sonic experience. However, in general I find that, in a long quarter-tone piece, the delicious strangeness becomes uniform, and settles into a monochrome grayness. It’s like being dropped on an unfamiliar planet: the initial thrill of exoticness gives way to relentless disorientation. The quarter-tone musical universe is too strange, and difficult to get used to. In this world the composer, faced with all those new available pitches – though of course there are sensitive exceptions in the music of Wyschnegradsky, Eaton, and others – the composer tends to exclude the familiar, and thus minimize contrast.

This is the principle according to which Ben Johnston’s microtonal music – and not only his music, but his entire approach to music – has always seemed stronger to me, more inviting, and more enduring in its appeal. Its starting point is the harmonies that have been used in music for hundreds of years. From that point it grows outward into more exotic harmonics, which we learn by hearing, as the fineness of our pitch discrimination increases, to incorporate into what we are already familiar with. Theoretically speaking, Ben, like Harry Partch before him, does not take a sudden left turn from 1920, as the quarter-tone composers did, but goes back to the tuning arguments of the 16th century and starts over. For the Renaissance musician, a sharp multiplied a musical frequency by the fraction 25/24 – and so does it in Ben’s music. In Renaissance music, major triads represented a set of tones vibrating at ratios of 4, 5, and 6 – and so they do for Ben. The C major scale represented the center of the musical universe, and a take-off point for more exotic phenomena – and so it does for Ben.

What happened in the 16th century, limiting our musical resources for the next 300 years, is that a decision was made to exclude the number 7, and all larger prime numbers, from our theoretical vocabulary. Under English influence in the 15th century during Henry V’s war of occupation, French

theorists were convinced to expand their tuning arsenal from 2 and 3, the octave and perfect fifth, to 5, which gave them a consonant major third as well. But when they came to the number 7, the seventh harmonic, despite the advocacy of certain intelligentsia like Nicola Vicentino and the famous mathematician Marin Mersenne, the theorists balked. The victorious Zarlino insisted on the infamous senario, the numbers 1 through 6, as the basis of musical consonance. He argued by analogy on the grounds that there are six directions (up, down, right, left, forward, and backward), six zodiac signs (as long as you count only the ones visible above the horizon), six visible planetary bodies (as long

as you don’t count the Sun), and so on. That there are seven days of the week, let alone 13 full moons a year and a 19-year cycle of sun and moon phases, he seems to have conveniently overlooked. The decision was cultural, political, and even racist, besides being sixist. The hindus and arabs used prime tuning numbers larger than 5, and the good Catholics of 16th-century Italy were not going to follow the path of the heathens. And so for over 300 years, Europe and then America sweated by on

12 impoverished pitches only designed for the playing of simple triads.

This was the decision that Harry Partch set out to undo in 1928 when he burned his early music in a pot-bellied stove in New Orleans and started over with the 7th and 11th harmonics. It was Ben Johnston’s contribution to create a notation in which to think musically with the 7th, 11th,

and even higher harmonics, and to pursue an expansion of acoustic-instrument performance practice with those harmonics.

The fact is probably already familiar to this audience, but I will recount it ritualistically, that in Ben’s most famous work, his Fourth String Quartet based on the common folk tune “Amazing Grace,” he gave us a vivid template in how to expand music through the harmonic series. The piece, as you all know, is a set of variations. The first statement of the theme uses only the primitive pentatonic scale of the French 14th century, based on ratios of 2 and 3 – also presumed to be the scale of rustic folk fiddling. The first variation adds in the pure thirds added by the fifth harmonic. The fourth variation adds so-called “blues” notes of the seventh harmonic, and the fifth brings in the seventh subharmonic, until at the end the music traverses a symmetrical 23-tone scale firmly anchored in the key of G- (that’s G minus, not G minor). At the very end, pitches are again subtracted precipitously, and the

music ends in a simple and familiar final cadence.

At the same time, of course, Ben opens the piece with the beat divided only into

simple 8th-notes and triplets. When he adds in the fifth harmonic, he also adds quintuplets to the rhythm, and as he folds in 7th harmonics he adds in septuplets, in systems so intricate that one variation is based on a structural polyrhythm of 35 against 36, which also happens to be the pitch ratio difference between a 7th harmonic and a regular Renaissance-era minor seventh. In this mirroring of the same numbers in both harmony and rhythm, Ben achieves in the work a beautiful manifestation of the vision Henry Cowell sketched out imperfectly in his 1930 book New Musical Resources. In that book Cowell theorized that the languages of pitch and rhythm could be developed isomorphically rather

than separately, as had been traditional. (Tomes have been written about Ben’s microtonal usage, but his role as a rhythmic pioneer, I think, has never been sufficiently acknowledged.)

Had Ben never written another work, this piece, the Fourth Quartet, would have been a sufficient blueprint for how music could expand its resources magnificently in the 21st and 22nd centuries. It is an ontogeny on which a phylogeny could be fashioned. All of my own music has taken place, rhythmically

and harmonically (even my non-microtonal music), within the expanded universe opened up by that piece – not simply because I studied composition with Ben, but because he solved, notationally, pragmatically, and creatively, the impasse posed by the premature moratorium on prime numbers higher than 5 adopted in the late Renaissance. (One could say something similar about Harry Partch, whose own rhythmic explorations have also been too little noted, but Ben solved it for those of us whose carpentry skills are less than impressive.)

I first met Ben around 1976 when I was a student at Oberlin, but I didn’t get to know him until 1983. At a wonderful concert of his music in Chicago, I went up to him and asked if I could study with him. I had already finished my doctorate, but I had never studied regularly with a very famous composer, so I asked to drive downstate to Urbana every now and then for a lesson with him. It turned out that he was also traveling to Chicago frequently to attend a Zen temple, and so sometimes I would meet him there instead, and eventually I started attending the Zen services with him before our lesson. What I didn’t tell him was what I was saying to myself: that although I loved his music, I wasn’t going to get involved in this microtonality business, because it was too much work for too little payoff.

Ben never proselytized for microtonality. But in my very first lesson, he made a casual comment about how nice one of my harmonies would sound if you tuned it properly, and he reeled off the fractions. I had been the star math student of my high school, and merely realizing that I possessed what it would take to enter Ben’s new harmonic world presented an attraction from which I was helpless to draw back. He didn’t need to encourage or convince me. I suddenly realized at that moment that a door had just shut behind me, and there was no return. I wrote very little music in my four years with Ben, but I filled entire notebooks with pages and pages of fractions. Not until 1991 did I finally manage to write a piece that was completely microtonal in conception, that couldn’t be meaningfully approximated on the piano. I figure Ben delayed my composing career by five years. But he bestowed upon me the heady pleasure of being able to compose harmonic progressions that had never been heard

before.

I can’t guess what might have happened if I had studied microtones with John Eaton or Easley Blackwood instead, but I do know that Ben’s approach made intuitive sense to me because it started with the familiar and moved out gradually and organically into the exotic – sometimes in a calculated and

dramatic fashion. I remember when I first started driving to Urbana that he would first bring in and enthusiastically play me the music he was working on. He’d start playing – I particularly remember this happening with his piece for trumpet and piano The Demon Lover’s Doubles – and the music would seem rather normal. A couple of minutes later, I’d start thinking, “Gee, Ben’s piano is badly out of tune, you’d think he’d call a piano tuner.” And then by the end of the piece his piano would have become miraculously in tune again. I was stumped. I didn’t understand tuning enough at the time to realize what was happening; I know now that his piano sounded more and more out of tune the further he strayed from the central key it was tuned to.

I want to replicate for you an experience Ben gave me once by playing you The Demon Lover’s Doubles. I used to have a recording of this on cassette, but unfortunately it’s been misplaced over the years, and so I’ve made a MIDI version whose quality I apologize for, but that will at least give an accurate representation of the tuning.

This is a subversive piece. It draws you into a false sense of security and then suddenly [at 2:28 out of 4:10] throws you into an abyss in which you doubt your own senses – and it does so with just a simple 12-pitch scale tuned to one key. Looking back, I’m embarrassed that at 28 I was too ignorant to fully get the joke. I’m also glad that I was forced to make a MIDI version, because it wasn’t until I added the dynamics that I realized how clever the conception is. The middle variation is loud and bangy, and then the music turns mysteriously quiet just as the last four disorienting pitches get

added in. The whole scale is tuned to the key of D, but those last four pitches – 15/14, 11/9, 15/11, and 14/9, if you’re keeping track – load in two more unexpected dimensions of the harmonic series. You’ve been riding along comfortably with 2, 3, and 5, just as your family had done for generations, and suddenly you get a visit from 7 and 11. This simple-sounding world is not what you thought. It contains a portal to the demonic world – a world that studying with Ben soon made me eager to enter. And the music raises your sense threshold with its grand loudness before suddenly sinking down to a pianissimo level at which not only are you hearing something really weird and unexpected, but you’re not quite sure what you’re hearing because it’s suddenly so soft. It’s one of the great sucker punches in music. And in 1985 I was a great sucker

I later found a more subtle example of Ben’s pitch magic in his Suite for Microtonal Piano of 1977. In this piece the piano is tuned entirely to overtones of C, specifically the 1st, 3rd, 5th,

7th, 9th, 11th, 13th, 15th, 17th, 19th, 21st, and 27th harmonics. According to one of the prevailing misconceptions about just intonation, this should mean that only music in the key of C major should be

playable in this scale. However, Ben couches the second movement in the key of D, and the fourth in the key of E with an interlude in G. Each of these movements sounds perfectly at home in its tonic key, yet each offers a different set of intervals to the tonic note, and thus a different repertoire of peripheral harmonies. In effect, Ben has invented the possibility of treating an unequal 12-pitch scale as a mode, with different potentials on each tonic. The scale contains only five perfect

fifths, and it is on these fifths that Ben grounds his basic harmonies. Exotic intervals available on D that aren’t available on C include the ratios 19/18, 11/9, 13/9, and 17/9. The range of chords on these pitches, which would sound jazzy but rather tame on a conventionally tuned piano, offer a vastly expanded range of consonance and dissonance of which Ben takes full advantage. The climactic chord progression ranges from a chord whose ratios would have to be analyzed as 27:32:44:52:72 down to one that is simple 2:3:4:6. This range provides an entirely new dimension between extremes of consonance and dissonance unknown in previous keyboard music. In 12-tone equal temperament, dissonance depends mostly on seconds and sevenths; on Ben’s piano, one has not only those but strangely tuned thirds and sixths, a completely different flavor of dissonance – or as Harry Partch memorably put it: “an entirely different serving of tapioca.

I’d now like to contextualize all this with reference to Ben’s quiet, little noted, but persuasive contribution as a music theorist. Though not as noisy or controversial about it as some other composers later were (notably one of his more outspoken students), he was probably, or seems so in retrospect, the first to publicly criticize serialism on theoretical grounds, and not from a conservative position, but from a radical one – not because it went too far, but because it didn’t go far enough. Much later, Fred Lerdahl would write a paper about “cognitive constraints” in which he demonstrated that our brains are not wired to process permutations as musical phenomena; years later, George Rochberg would publicly stop writing 12-tone music and scandalize his colleagues by returning to Romanticism; soon, the first minimalists would return to writing in a diatonic scale. But before all of these, as early as 1959, Ben was writing about the limited intelligibility offered by an interval scale in a 12-tone context. In 1962 he drew on then-recent findings in experimental psychology to draw a distinction between nominal, ordinal, interval, and ratio scales:

A nominal scale is a collection of equivalent and interchangeable items. An ordinal scale is a collection which is rank-ordered in terms of some attribute. An interval scale is a rank-ordered collection in which the intervals of difference between items are equal. A ratio scale is a rank-ordered collection in which the items are related by exact ratios…. Each of these scales includes all of the measurement possibilities of its predecessors, plus one more.[1]

The major and minor scales of European tonality are ratio scales, because it is possible to judge the ratio of each frequency to the tonic. Twelve-tone method gives us only an interval scale, because all we can hang on to are a group of intervals whose size differences are uniform. It is because the methodology of 12-tone music allowed only for interval scales and not ratio scales that Ben was able to announce that, “in an important and basic way serialism is… a less sophisticated technique than tonal organization.”[2]

As long as the basis of music was triadic, he wrote, the out-of-tuneness of

12-tone equal temperament was of negligible importance, but in the long run the

system offered an inadequate conceptual model for expansion. “When many of

these usages become outmoded,” he wrote,

and a search for new principles of musical organization

begins, as has happened in the 20th century, the one-sided model

provided by equal temperament becomes a serious but largely unrecognized

limitation. When musical organization based upon a linear (interval) scale

replaces that based upon a ratio scale, there is a net loss in audible

intelligibility.[3]

Note, however, that unlike other

composers who identified a fatal flaw in the 12-tone language, Ben didn’t stop

writing in it. I once asked him why, since he was a just intonationist, he

continued to write 12-tone music, and he answered, “Well, I had learned all

that technique, and I didn’t want it to go to waste.” In his 12-tone music,

though, he applied his own critique as a reform. In his remarkable String

Quartet No. 6, the first hexachord of the row is a harmonic series on D, and

the second is an undertone series on D#. This means that all 12 notes of the

row are not equal in weight, because one note in each half of the row is the

fundamental from which the other five pitches are derived. The pitch matrix for

this row contains 63 different pitches within the octave. The piece rocks back

and forth between overtone series’ and undertone series’, in a thoroughly

tonalized 12-tone technique.

Ben’s point of view, reaching back

into the Renaissance and breaking with some of his immediate contemporaries,

brought him to take stands that were both radical and conservative. As he wrote

in 1976:

Feeling that the harmonic mode of pitch perception is far too important a resource of human capability for it to be allowed to fall into disuse, I have set about to reestablish ratio scale usage in pitch organization. This has entailed a number of radical means (large numbers of microtones, for instance, entailing new performance techniques, especially for wind players), some strongly conservative practices such as the resumption of a sharp awareness of degrees of consonance and dissonance as a major musical parameter (which amounts to revoking Schoenberg’s much-touted “emancipation of the dissonance”), and even some radical reactionary attitudes, for example, the

rejection of the idea that noise, “randomness,” and ultracomplex pitch are the primary frontiers for avant-garde exploration.[4]

I’d like to add to Ben’s critique the complementary formulation expressed by George Rochberg, another excellent 12-tone composer who decided there was something wrong with the idiom. According to Rochberg, every new era in music history took the previous era’s practice as a basis and added to it. Not until the atonal period ushered in in the 1930s, he wrote, did musicians begin to prohibit use of the resources that had served previous composers. The 12-tone style mandated an avoidance of octaves, an avoidance of triadic points of tonality, an avoidance of evident regularity. And as Rochberg wrote, an aesthetic based on negation and prohibitions cannot serve the human race for long. As Ben put it,

It is clearly necessary to generalize the concept of tonality if it is not to be abandoned altogether. The solution should have the characteristic of including traditional methods within it, as special, limited cases.[5]

I don’t know how, or to what extent, this attitude seeped into my mind through Ben, or how much it simply made irrefutable common sense. But I do know that in 1983, around the time I started studying with Ben, I overcame a deeply ingrained, college-implanted artificial squeamishness, and started composing in triads. It has seemed increasingly obvious to me that we can’t achieve our greatest potentials in music without using all the effective musical devices that served composers in the past, as well as adding those innovations which are unique to us. Serendipitously, Ben turned out to be the

perfect mentor, not only to allow that large thought to settle, but to stretch it out in both directions, past and future, to make it seem infinitely commodious and inexhaustible.

There are many, many different approaches to microtonality. All of them are valid.

Each one suits a different set of creative needs. In the long run, some will turn out to have been more fertile than others. For me, it is this capacity of Ben’s approach to reach deeply into the past, and yet remain open-ended with regard to the future that makes it the most rewarding. It satisfies my need for history, flatters my limited mathematical talents, gives me adequate means for organizing only five pitches to the octave or 500 as I need at the moment, and offers me an infinity of potential organizations, absorbing even 12-tone music itself into the ongoing evolution of tonality. I’ve always loved the words that Ben wrote in his original liner notes to the “Amazing Grace” quartet. Because

that piece is so well known we forget that it is part of a pair with the Third Quartet, which is serial in technique, and that in performance there is a mandatory 60-to-120-minute silence between them, symbolizing the abyss between one kind of musical practice and another, more fertile one. Ben writes,

It is an amazing grace to have come through an abyss. It is

an amazing grace to see once again that the simplest and purest of

relationships are the means to cope with the multitudinous and complex.[6]

It

seems to me that in this era of economic scarcity and questioning of the great

tradition of classical music, we have reached a temporary endpoint in the

extent of music’s outward development. The achievements of Stockhausen and

Brant with multiple orchestras are going to be difficult to surpass any time

soon, or even equal, and for most of us, even a conventional orchestra seems

out of reach – and when it is within reach, we can’t get enough rehearsal time

to try anything innovative. Exceeding the length of Feldman’s chamber pieces,

Glass’s operas, and John Luther Adams’s sound installations is a daunting and

possibly barren prospect. My prediction for the future, partly based on the

curiosity I’ve been sensing among young composers about microtonality, is that

for the next few decades the impulse for musical innovation will go inward to

its own materials rather than outward. Ben’s notation, his theoretical

framework, and the example of his music have already provided us with a map of

the vast inward musical universe whose exploration will take us decades if not

centuries. I read interviews with pop musicians and classical musicians who say

that everything’s already been done in music, all we can do is repeat. And I

remember the door onto a new universe that Ben opened for me, and I think,

“What in the world are they talking about?”

[1] “Scalar

Order as a Compositional Resource” (1962-3), in Gilmore, Bob, ed., Â Maximum Clarity, p. 10.

[2] “Musical

Intelligibility” (1963) in Maximum Clarity, p. 99.

[3] “Scalar

Order as a Compositional Resource” (1962-3) in Maximum Clarity, p. 14.

[4] “Rational

Structure in Music” (1976), in Maximum Clarity, p. 62.

[5] “Musical

Intelligibility” (1963) in Maximum Clarity, p. 99.

[6] Ben

Johnston, liner notes to Fine Arts Quartet, Gasparo CS 203.

Me and Ben with Momilani Ramstrum at Wright State University, March 14, 2010.

Keeping the Score

The other day I heard a music publisher inveigh against composers who post their scores for free as PDFs on their web pages. I am one of that tribe. His argument, which was new to me and interested me, was that those composers pose unfair competition to the composers whose scores are published, and thus cost money. I have trouble crediting this argument. As much as I’d love to think that my music has an inside track because people can get the scores for free, it’s difficult for me to believe that any performer or ensemble ever makes a repertoire choice based on the cost of the score. The only such cases I’ve ever heard of are orchestras that have decided against performing certain pieces because the orchestral parts cost too much to rent, and those cases didn’t even involve living composers. I suppose it’s possible that if, say, John Adams were giving his scores away for free and David Del Tredici wasn’t, perhaps there are a few ensembles who would choose Adams over Del Tredici for that reason, but I doubt even that. It seems to me that people choose repertoire based on what music fits their ensemble, or their performance technique, or their stylistic programming, and score prices are hardly so exorbitant as to become a determinant.

1. The notation needs considerable work to be readable; these are pieces that are either microtonal (often in indecipherable MIDI notation), or partly improvisatory, or electronically produced without a full score, or incidental music for a dramatic production that would hardly make sense out of context, or otherwise insufficiently notated.

2. Scores that were commissioned by performers who requested temporary exclusivity over performance, and I consider such exclusivity rather expensive, though certainly negotiable.

3. Scores on which I imagine that I could eventually make a considerable amount of money. The only score that falls into this category so far is Transcendental Sonnets, of which I post the orchestral score but not the vocal score or the two-piano performance version. Choral pieces have the potential of selling a tremendous number of vocal scores because so many singers are involved, and so I have thought it unwise to send vocal scores out into the world for free – although I have done that with My father moved through dooms of love, which has no score other than the full score. Since I will gladly send a PDF of the vocal score to any chorus interested in a performance, even this small scruple on my part seems superfluous, though I might change that policy if the piece became wildly popular.

Reality Beyond Imagination

A composer imagines a piece of music in its entirety. Many decent performances don’t quite recreate the piece as one heard it in his imagination. Sometimes one gets really lucky, and a performance exactly matches a piece as the composer heard it in his inner ear. A few times in a composer’s life, a performance goes beyond what one’s heard in his imagination. Not only is every detail of the notation heard in acoustic reality, but immanent structures within the piece are brought out, exaggerated as it were, and the composer hears and becomes aware of things he only inchoately or subconsciously intended. The performance becomes a result of not only what he wrote, but of what other people began to imagine as they internalized the notation. The performance is not merely a perfect realization of what the composer imagined, but a collective creation, a collaboration of superbly musical musicians all focused on the piece, that goes beyond what the composer was able to imagine by himself. I’ve had this happen frequently with performances of my piano works by Sarah Cahill, in part with the Orkest de Volharding’s recording of my piano concerto Sunken City, and with Aron Kallay’s performances of my microtonal keyboard pieces. And tonight it happened in a dramatic way with the Dessoff Choir’s performance of my Transcendental Sonnets, conducted by James Bagwell. The acoustic reality achieved what I’d imagined, and went beyond it: sonorities swelled and shaped beyond what I could have notated, continuities aligned into innovative textures I’d only partly heard internally. In particular, the choral seventh chords in the final movement flattened into a mystical backdrop against which the soloists (Megan Taylor and Jeffrey Hill, singing gorgeously) were foregrounded in a way that I realize in retrospect I’d subconsciously hoped for but didn’t know how to achieve. In the first half of that movement the text isn’t intelligible because it’s unsynchronized among the SATB parts, which was intentional, though I’ve been criticized for it; tonight it truly became a kind of ecstatic speaking in tongues slowly resolving into understandable words. The piece took on a life of its own for which the notation could be only partly responsible. Physical reality is thought of as an imperfect reflection of Platonic forms, but, contrary to theory, sometimes in the fusion of collective creativities the physical rises above the ideational. That happened tonight.Â

The Joe Biden of Ivesiana

Today I

was voted vice-president of the Charles Ives Society. My term officially begins

July 1. This is the highest peak to which I have ever acceded in electoral

politics, and the highest I ever expect to attain. I harbor no presidential

aspirations. Aside from state funerals, ship christenings, and the like, I imagine

my role as vice-president being to shoot my mouth off in wild public

misstatements from which the new president, scholar Gayle Sherwood Magee, will

be forced to tactfully distance herself. No other candidate, I’m sure you’ll agree, could have been nearly so well-suited for such a job as myself. Seriously, though, it was a tremendous kick spending the day among the most august of the Ives experts and getting an inside look at the progress of upcoming editions, attempted landmark preservations, and so forth. The spirit of the late Wiley Hitchcock was among us – even though I’d never been in the group myself before, I could feel how anomalous his absence seemed.

Tomorrow

evening (Saturday) maestro James Bagwell will direct the Dessoff Choirs in my Transcendental

Sonnets at

Merkin Hall in New York City at 8 PM, along with works by Harold Farberman and Lukas Foss.

Harold and I will indulge in some pre-concert fisticuffs with an interviewer at

7:30.

Next

weekend, March 13 and 14, I will be at Wright State University in Dayton, Ohio,

for a microtonal conference in honor of Ben Johnston and Owen Jorgensen, where,

at 5 PM on Saturday, I’ll deliver a keynote address about Ben.Â

Boulez on Music 22 Years Ago

Today I ran across a box of audio cassettes that has been misplaced for years. Among many treasures are my interviews with Boulez, Yoko Ono, Trimpin, Ashley, Branca, Mikel Rouse, and a few others, plus about ten cassettes’ worth of Nancarrow. I thought the Boulez interview might be of particular interest. It took place in a hotel room in Chicago on October 27, 1987, when Boulez had come to perform Repons and conduct the Chicago Symphony in his Notations and other works. This was back when I’d only been at the Voice a few months, and I was interviewing him for the Chicago Reader, where I’d been free-lancing for five years. The whole interview is 67 minutes, and some of it is a little dated, talking about the impending possibility of classical music’s dying, which of course 22 years later we know is apparently not going to happen. But I’ll put up the most interesting snippets, totaling almost half, from the interview here:

Am I Getting Overexposed Yet?

My new book was mentioned today in the New Yorker, and my music in the New York Times. The latter sort of implied that my Disklavier music is “silly.” Personally I think classical music should lighten up and indulge a joke now and then, but I’m finding that when you write a humorous piece, people are just disturbed by it. I guess it’s back to solemn and portentous for me.

Concert Reminders

Too Soon to Celebrate

Critic Anthony Tommasini’s piece in the Times today is headlined, “Dogma No More: Anything Goes.” Isn’t that a wonderful

pronouncement? And the occasion for the article is his realization that young

musicians these days are open to all styles, and no longer care about the

aesthetic battles of the past. His evidence is a concert by the Ensemble ACJW

that included a wild and eclectic mix of composers: Stockhausen, Babbitt,

Berio, Davidovsky, Daniel Bjarnason. “Categories be damned!,” Tommasini

cries. Amen to that, and thank goodness musical politics have ceased to sway

us. But wait a minute: I hadn’t heard of Bjarnason, but I thought Stockhausen,

Babbitt, Berio, and Davidovsky were composers who tended to all be championed

by the same people all along. So I looked up Bjarnason, who’s a 20-something

Icelandic composer whose music is nominally tonal but dramatically virtuosic,

and I have noticed, for years, now, that the same young musicians who champion

atonal hardliners like Davidovsky and Babbitt also seem eager to find young

European composers whose music is dramatically virtuosic. That those who

champion complexity, drama, and European values in the old music champion it in the new as well

hardly comes as a surprise.

And

Tommasini notices a problem too: while today’s young musicians are open-minded

enough to accept not only Davidovsky but Bjarnason, they seem to avoid composers of a milder, more neoromantic bent, like Barber, Harbison,

Christopher Rouse, and so on. Tommasini calls those the “mainstream” composers

(young composers in that tradition have insisted to me that I refer to them as

“Midtown”), but he also quotes Harbison’s self-applied term “notes-and-rhythms

composers.” Now, this is ironic, because the interview with me that’s in the

July, 2008, issue of Musicworks magazine is titled “Pitch and Rhythm Guy” because that’s how

I referred to myself during the interview. The term would apply equally well

to dozens of postminimalist and totalist composers I wrote about in the Village

Voice

during the 1980s and ’90s. In fact, I once explicitly made this connection in a

book: “If Copland, Harris, Barber, and their ilk represented a first wave of

American diatonic consonance, postminimalism is the second.” Of course, the

postminimalists, Zen-oriented and antivirtuosic, represent an entirely

different world than the mainstream neoromantics. And not only did no one in

the postminimalist crowd make the ACJW playlist, they didn’t even make

Tommasini’s round-up of the

current panoply of styles among which today’s young composers no longer

discriminate.

Few

critics have been as sensitive to the damage done by aesthetic style wars as

Tommasini has, and he’s scored some valiant points against the intolerance of

the high modernists. But if he’s going to convince me that the days of dogma

are over, and anything truly goes, he’s going to have to at least acknowledge

that the large milieu of nonmainstream composers I write about exists.

Otherwise, his failure to include us – and him of all people – just makes it

look like certain doors are as tightly shut as ever.

The Objective View

Two boxes of my book No Such Thing as Silence: John Cage’s 4’33” arrived this week, the first time I’ve had a book and CD come out the same week. (Today I also received an announcement that an Italian edition is under way.) And although Amazon still has the release date as March 23, I’ve already gotten a nice review from Publishers Weekly. Especially gratifying were these lines:Â Â

Two boxes of my book No Such Thing as Silence: John Cage’s 4’33” arrived this week, the first time I’ve had a book and CD come out the same week. (Today I also received an announcement that an Italian edition is under way.) And although Amazon still has the release date as March 23, I’ve already gotten a nice review from Publishers Weekly. Especially gratifying were these lines:Â Â

Following a biographical summary of Cage’s early musical development, Gann considers the various influences that got him thinking about “silence, meditation, and environmental sound,” from 20th-century composer Erik Satie back to the medieval mystic Meister Eckhart, moving on to a sensible reconstruction of the piece’s development–down to telling details like the fact that its length is roughly the same as the temporal space on a 12-inch 78 rpm record. [Thanks to my readers for that latter insight.] Though Gann clearly respects Cage and 4’33”, he doesn’t worship either blindly, and that critical appreciation makes his argument that this is a radical “act of listening,” not a provocative stunt, all the more compelling.

Internalizing Absurdity

My CD of The Planets has arrived. One friend has already received the copy he ordered directly from Meyer Media. You can hear some excerpts there, and I’ve left two movements up on my web site as teasers: Venus and Uranus. And I thought I’d brag a little about what I did in Uranus, one of my favorite movements.

Erasing the Timeline

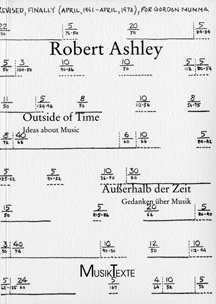

We have recently – about fifty years ago – come upon a new idea in thinking about music, but I think it is not even approached in theory. This new idea does not use the

timeline score….ÂBy timeline music I mean music having any number of parts, a piano score or an orchestra score, that are coordinated by bar lines. This music must, by definition, be

“linear.”…ÂCuriously, the most famous proponents – for Europeans and Asians as well as Americans – of a new kind of music among American composers, John Cage and Morton Feldman, could not escape from the timeline practice. They made wild (sometimes seemingly desperate) attempts to make a new kind of music, but their attempts were fundamentally still trapped in the timeline way of thinking. (I don’t mean that their music was unsuccessful… I mean that to attribute to these two composers

the kind of radical departure that one recognizes in Wolff or Brown, Behrman,

Lucier, Amacher, Niblock, my own music and a few younger composers, is wrong.)ÂFor everybody else who appeared around 1960 and is still around – Babbitt, Wuorinen, Reynolds, and countless others – there is no question that they ignored the message and continued exploring the timeline.Â

The first evidence of the non-timeline music came around 1960. (Typically, it was around earlier – especially in Wolff and Brown – but it really began to “flower” after 1960. It is hard to know whether Wolff or Brown realized what they were doing to the

history of music. This is not to detract at all from their work – or their intelligence about their work – but, as I have maintained, the manifestation of an idea seems to happen before the idea is recognized and described….)ÂAnother “historical” fact to be recognized is that the reaction to the practice of non-timeline music, particularly in the form of “minimalism” and “postromanticism,” came not more than ten years after a lot of composers started doing non-timeline music. In other words, non-timeline music was very important and, in the case of the reaction to it, something

perhaps to be feared. As if some composers were leading us in the wrong

direction and things had to be corrected.ÂIt’s true, of

course, that “time” passes while music is being played and while it is being

listened to. But in non-timeline music (the drone) the time passing is not

“attached to” the playing or the hearing. Time passes in the consciousness of

the listener according to internal or external markers.ÂThe feeling of

timelessness can be created in a traditional timeline score using an extreme

version of the timeline technique. That is, by pushing the timeline technique

to an extreme of what can be written in a timeline score, I remember this,

without being able to cite examples, from certain Earle Brown scores. The one

example I can cite is Somei Satoh’s Kyokoku. In this score for voice and orchestra

Satoh uses a very slow tempo (twenty beats per minute) and allows that in

certain sustained sections the conductor can slow the tempo even more, or can

stop the tempo entirely. In these sections the feeling of timelessness is

evoked….ÂNon-timeline makes

no attempt to keep the attention of the listener. It exists as if apart from

the attention of the listener. The listener is free to come and go. When the

listener attends to the music, there is only the “sound.” The sound is

everything. When the listener is away, the music exists anyway. This is

certainly a new idea….ÂI have called this

new idea the “drone,” because there is no better term that is not a neologism –

like non-timeline music. I have said that I use the term “drone” to mean any

music that seems not to change over time.

Or music that

changes so slowly that the changes are almost imperceptible. Many composers

make this kind of music. The best known to me, offhand, are Behrman, Lucier, Radigue,

Tone, Payne, Bischoff, Hamilton, along with others.ÂOr music that has

so many repetitions of the same melodic-harmonic pattern that the pattern is

clearly secondary to another aspect of the form. Philip Glass’s early music is

a good example. (Glass recently has more and more reverted to the timeline

style.)ÂThe non-timeline

concept has permeated my music, though because of my deep involvement with

speech rhythms and opera, I have not composed much music that is pure

non-tineline.

My early music –

prior to 1980 – is much more clearly exploring the non-timeline concept. After

1980, when opera became the most important fact of my work, I began using

certain aspects of the traditional score to coordinate many performers’ actions

(musical events) at any moment in the linear time pattern. I am still trying to

escape from that constraint, but so far unsuccessfully….ÂWhat is in the

nature of non-timeline music in the operas is the technique of allowing the

harmony to continue for so long in a particular aria that harmony loses its

traditional meaning….ÂThe purpose is to

create an intense self-consciousness in the listener, a kind of “meditative”

state of mind. Of course, as in meditation, as I understand it, the attention

in the listener will change constantly and is the responsibility of the

listener. The composition exists “apart from” the listener, a musical fact to

be observed and appreciated at the will of the listener….ÂIn a simplistic

explanation of “non-timeline” music the composer’s purpose is dedicated to the sound of the work. The sound is everything. The

sound has no temporal dimensions. It exists apart from the listener’s

participation. In non-timeline music nothing happens. The sound is simply

there. [Variations on the “Drone,” 2004; pp. 114-124]Â

Ashley’s liner notes to Phill Niblock’s Disseminate CD (Mode 131):Â

The “drone” is one

of the special contributions to musical technique in the second half of the 20th century. I use the term “drone” – though most composers who will be named below

will resent the term – because I can’t invent another term or phrase that is

not just musical jargon and that is not more understandable.ÂThe drone has two

pronounced characteristics. The first and most obvious is an unchanging, or

barely changing, pitch. This characteristic, notably, is also the rarest among

various composers’ “signatures.” Most composers moved away from the unchanging

pitch technique almost as soon as they got involved with the drone….ÂFundamentally the

drone disregards pitch change. And so the musical time seems to stop. This lack

of eventfulness is a challenge to the listener that the composer of any form of

drone music must live with (and/or “solve” by some other technique)….ÂA second

characteristic of the drone, but I think part of the same tendency, is a

quality of unchanging tonal “color”; that is, an unchanging instrumental sound,

regardless of what other elements of musical composition are employed. One

could name any number (a large number) of composers who work in this area.

These composers have abandoned the “narrative” or “dramatic” notion of the

orchestra as a collection of “characters”….The drone seems

peculiarly American. The reasons are probably many.ÂNo American

ensemble would play any living composer’s music in the 1950s, and so any new

technique that deviated from the performer’s conservatory training was

discouraged. One could call that situation a form of poverty (for the composer)

and a deciding factor in the invention of a new technique. But, of course,

historically poverty has produced a lot of changes in music.ÂAnother reason, I

believe, was the American composer’s unusual interest in the music of other

cultures, particularly (because they were available on records) the various

musics of Southeast Asia, the various musics of Africa and the various musics

of the marginal black and marginal white isolated cultures in the United

States. And all of these musics seemed to have fewer “changes” and a simpler

“architecture” than the music we had inherited from the concert stages of

Europe.ÂBut most important,

I think, was the advent of electronic music. Prior to the use of electricity

the energy source for music was physical (human) and the limitations on that

energy source had to be accommodated in the music. The music had to rest, had

to be softer for awhile, had occasionally to be texturally less dense. With a

new source of energy coming from the local utility company all of that changed.

Conceptually, the music could go on at any level of intensity forever….Â

excerpting from much longer articles I haven’t created a false impression of

any of Bob’s ideas. Those inclined to criticize might want to consult the

complete originals before so doing. We have a paucity of narratives for what’s happened in music in the last 60 years, and this one, from one of the era’s major

players, is particularly valuable. I’ve written my own narrative, of course,

which Bob’s conflicts with at several points. Of particular interest is that,

having come from the revolutionary, score-rejecting ONCE festival scene of the

’60s, he lumps much minimalist music into the conservative reaction against that scene. Coming along myself in

the ’70s, I think of the ’60s, ’70s, and early ’80s as the great liberal era in

music’s history, whereas for Bob the ’70s were already a turning back towards

comforting convention. Not having been there, I can only honor his perspective.

importance is his concept of the drone, which does indeed draw a sharp line through the group of

composers lumped into the generic term minimalism, separating traditional

timeline composers like Andriessen and Adams off from the more radical

composers like Niblock and Behrman (and Charlemagne Palestine? though Bob never

mentions him) who compose unchanging (or slowly changing) sounds. This division

is one the Society for Minimalist Music will want to confront at some point. I

hope to bring this Ashleyan critique to bear in my contribution to our 2011

conference in Leuven. Whenever someone tells me that someone they know in

academia is “sympathetic to minimalism,” I always wonder: you mean simply that

they’ve learned to re-accept diatonicism in timeline music? or have they realized that a piece of music need not contain any events? If only the first, I’m not impressed.

music is less radical than the music Bob champions in these descriptions.

After some early forays into Riley-like free repetition, I became rather

addicted to the timeline. I’ve always been more interested in refining our

perception of pitch and rhythm within a conventional format than in larger

exploration of form and modes of listening. And yet I sometimes – I could cite

my pieces Solitaire, Kierkegaard Walking, Implausible Sketches, Time Does Not

Exist, Cosmic Boogie-Woogie – use the timeline to create what I think of as a drone-like effect, in

which the continuing sound

of a melodic complex changes internally but not externally, and the linear

succession of sound complexes, if any, is almost arbitrary, as in the old joke “Time is

God’s way of keeping everything from happening all at once.” Bob’s

categories are different from mine but compelling, and give me a lot of food

for thought. I hope they do for you too.)

How to Read

Being of an age, and begging the indulgence of my seniors among my readers, I’m going to step into professorial mode for a moment and give a little lecture on reading comprehension. I suppressed a few negative responses I received to the recent excerpt I posted from Bob Ashley’s new book, both out of respect for Ashley and because they didn’t really engage what he said. Perhaps the fact that it was his writing being reacted to and not my own gave me an opportunity for a little more objective view into the reflexes of blog reading.

Two major things struck me about Ashley’s passage that I quoted. One was his scathing critique of the attenuated place of art in western society, as seen from an experience of other cultures. Certain Asian and African cultures are more pervaded by music, art, and dance than ours, more informed by frequent social rituals involving entire communities. This phenomenon has been expounded upon for decades now by ethnologists and historians of Third-World art from Ananda K. Coomaraswamy to Ellen Dissanayake and beyond. I myself have written about it repeatedly from my slim experience of Native American performances: at powwows at Hopi, Taos, and elsewhere, every single inhabitant down to the smallest toddler strong enough to lift a drumstick is engaged as a singer, dancer, even composer, only the Whites are mere spectators, yada yada yada. Ashley’s point, that the entertainer/consumer paradigm of American society deprives us of this intense social art experience, is hardly unusual or controversial, though it is presented here with striking vividness and in terms that musicians can easily identify with.Â

The astonishing thing about the passage I quoted was that Ashley offers this critique, not from the enthomusicologist’s conventional standpoint of immersion in Indonesian or Ghanaian culture – but from the standpoint of the ONCE festivals! The rhetorical trick of the passage is that it focuses on widespread contemporary practice and seems to mention the ONCE festivals only in passing: “The reproach to what had gradually come to be the feeling that music was everywhere, that you were part of it and you were actually in it in your daily life was enforced for some cultural reason I cannot understand.” But in reality, the ONCE festivals are the focus. Ashley is telling us that the ONCE festivals in Ann Arbor in the ’60s created the same sense of art pervading a community that one gets from living in Bali or Tehran or Lagos, that once you had your worldview conditioned by the ONCE festivals, coming back down into the relative superficiality of American so-called culture was a tremendous let-down. It’s an extraordinary claim, and made with disarming rhetorical cleverness. You read someone describing the innocent platitudes with which we are all familiar in such contrarian terms, and you wonder, from what experience did he come that he can afford to take such a jaundiced view of our daily lives? And that leads back to the question: Gosh, what must the ONCE festivals have been like, that afterward one would ever after resent what to the rest of us is mere normality?

Now: did Ashley say recitals were awful, and he never goes to them? No. He says, “Recitals are a curse,” and it’s an admirably exact formulation. They are a curse because we artists are forced to try to project the potential effects of art through this unequal entertainer/consumer relation, with one hand tied behind our backs, so to speak. Doesn’t everyone feel this? I certainly do. Since Ashley disparages entertainment, isn’t he just another elitist saying that composers shouldn’t be required to entertain? Quite the opposite: he is saying that music should entertain and do much more than entertain, that it should grip and transform us and its effect should last long after the actual experience has ended. Isn’t he making fun of world music, which has so enriched American culture? I think he’s saying that the reduction of gamelan to a recital performance creates a facile and dangerous false impression, and threatens to destroy something special in other cultures that our music lacks. Isn’t he just bitter? Well, I’ve yet to meet a composer who doesn’t have his or her bitter moments, but Ashley’s one of the least bitter composers I’ve ever met, and I read no bitterness in this passage. I see it as an enormous public service to remind us all from time to time that art can have a much higher and more potent role in a society than it currently does in ours. No one, no one is really satisfied with the status of contemporary music in today’s world. Shouldn’t those who’ve seen first-hand how things could be better do us the honor of showing us a potential goal toward which we could pragmatically strive?

I can imagine someone reasonably disputing Ashley’s argument. For instance: “I was at the ONCE festivals, and they weren’t as transformative for the community as Bob thinks.” Or maybe, “I’ve lived in Bali for 30 years, and among locals there’s more of a spectator aspect to gamelan performances than Mr. Ashley imagines.” Those might be true, might not be true, but at least they would engage the accumulated meaning of the entire passage. I’d even appreciate a broad, well thought-out defense of the Western concept of art that took the ethnological critique into sympathetic account. But the negative comments that came in were reactions to isolated sentences, and I hardly have time to defend every writer I quote (though I’m doing it for Bob now), or my own writings, from potential implications of particular sentences when those implications are nuanced and limited and even subverted by the meaning of the passage taken as a whole.Â

This brings to light, perhaps, an important difference in modality between blog reading and book reading. I’m reading the book; if I run into a passage, a sentence, that seems shocking or questionable, I don’t put the book down and phone Bob to dispute him; instead, I keep reading. As I do so, further paragraphs put former ones into perspective. The accumulation of new ideas begins changing my mind in ways that make the previous stumbling blocks seem more logical. On a blog, however, I’m beginning to suspect that the tempting proximity of that comment button works against the cohesion of entire passages, as readers scan for sentences that touch on some subject they have a pre-formed experience with or opinion about. The eagerness everyone exhibits to be an active part of an intellectual community is a touching aspect of what the internet has brought out in us all. But I could almost wish there were a function that could sense whether a comment was positive, neutral, or negative, and in the last case, flash a warning question: “Have you reread the entire blog entry to make sure you understand its full argument? Y/N.” This is why blogs, and electronic print in general, will never replace books. The stolid unmalleability of a printed book forces you to live for a while with the ideas therein, and give them a chance to transform you.Â

This semester for the first time in ten years I’m again sitting in a classroom on the students’ side: I’m taking a course called “Kierkegaard: A Writer’s Identity” taught by my brilliant friend Nancy Leonard. God bless me, I’m rereading Either/Or for the first time since the 1970s, and having a blast. So I finished “Diary of a Seducer” and, far more mature than I was last time I read it, I accumulate a million objections to Kierkegaard’s fevered fantasy – and then I turn to the Or volume, “The Aesthetic Validity of Marriage,” and, bing, bing, bing, bing, – Kierkegaard has anticipated my every objection and then some, and then I start to form reservations against that argument as well. Imagine Kierkagaard as a blogger, indulging in wild psychological flights only to contradict them later after his readers had already been fooled into commenting: impossible. And yet he wrote one of the most voluminous journals that’s ever been published, and I’ve been thinking a lot about the extent to which a blog is a public journal. I kept a journal when I was in my 20s, which got replaced by my newspaper writing in my 30s, whose impulse has been transferred to this blog in the last several years. Kierkagaard’s journals, of course, weren’t published until long after his death. Had his writing of them been conditioned by a consciousness that each one would immediately gather a string of comments, we would doubtless have lost one of the world’s great psychological treasures.Â

We don’t yet know where this blog thing is going, or what new kind of reading modality it’s going to lead to. Despite my grumpy resentment of selected new gizmos, I’m really no Luddite at heart, and I have an instinctive faith in mankind’s ability to adapt healthfully to new technologies. It would be ridiculous to have a 30-minute timer on the comment button to force each reader into half an hour’s reflection before objecting – but it would certainly have a salutary effect in numerous cases. Perhaps I simply create problems by forcing book-style content into a blog format where it doesn’t belong. But I think I’m too addicted to book-style content (and too little attracted to the links-of-the-week mode of most blogs) to do otherwise.