I still have a couple of full days this week, but the bulk of my school work came to an abrupt halt last night, giving me today my first chance to breathe in weeks. Except for their orchestral performances this Friday, my seniors are pretty much packed off into the world to start figuring out, come Sunday, what they’re going to do with their lives.Â

I didn’t get a chance to write about the contemporary music festival at Sam Houston State University at which I was the featured composer. I spent several days that week on the street that Kate Winslet runs up, trying to forestall Kevin Spacey’s execution, in the film The Life of David Gale. I highly recommend the movie, and the surprise ending is too good to tell you much about it. It’s about the Texas prison system, and the “walls” unit at Huntsville, Texas, where prisoners are executed and where the ending of the movie takes place, is two short blocks from the SHSU music school. A few years ago in real life, someone on death row shot a guard, escaped, and hijacked a car being driven by the music department’s piano tuner, holding her hostage for a few hours. She’s reportedly still in therapy about it. (Puts Bard’s inconveniences in perspective, I guess.)Â At 1:55 in the film you can see a corner of the music building behind Kate Winslet as she’s running – unfortunately, I forgot to take my camera, and can’t give you a comparison shot. I got kind of a kick out of it, and also out of the excellent local barbecue.

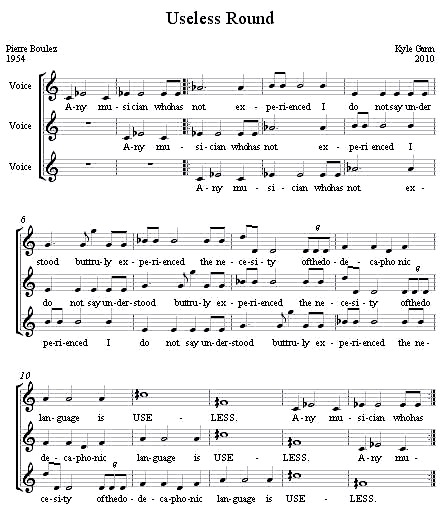

Also from the honor and the performances, highlights of which came from John Lane’s superb Percussion Ensemble, which played all three of my Snake Dances on one concert; and from my old friend Rob Hunt, who was among my inner circle at Skyline High School in Dallas (back when it was the arts magnet school), and who now teaches piano and accompanying at SHSU. I also enjoyed meeting SHSU composers Brian Herrington, Carlo “Vini” Frizzo, Kyle Kindred, John Crabtree, and Trent Hanna, who had pieces performed. All are considerably younger than me (while at 54 I’m still the youngest composer at Bard), and it was refreshing to spend a few days among young music professors with new initiatives and ideas. It’s quite an active and varied music scene down there – and I found it similar to music schools in the 1970s midwest in terms of being very stylistically open-minded. It’s so ridiculous, in 2010, to be otherwise.

As a result of that and other events, I’ve got a spate of new recordings up on my web site. While I was in Texas, John Kennedy conducted my orchestra piece The Disappearance of All Holy Things from this Once So Promising World at Oberlin, creating my first usable recording of that piece; and at Ball State guitarist Derek Johnson made a nice studio recording of my electric guitar quartet Composure (with Collin Marone, Zachary Barr, and Andrew Cowling). From SHSU I got a recording of the premiere of Snake Dance No. 3 and a couple of early songs no one had ever sung before (Jacklyn Kuklenz and Rebecca Costillo, singers). So here’s some 38 minutes of new recordings:

Snake Dance No. 3Â (11:29)

Composure  (13:43)

The Disappearance of All Holy Things (11:38)

I Slept and Dreamed that Life Was Beauty (1:45)

In the Busy Streets (0:43)

The final two songs, with texts by Ellen Sturgis Hooper and Henry David Thoreau respectively, are from a projected song cycle of Transcendentalist songs that I never got very far with. Their stylistic anachronism may seem puzzling; I was much taken, at one point, with Ezra Pound’s concept of setting poetry to music as a species of literary criticism, and I always tried to fit the music to the style and milieu of the poem.Â

I didn’t finish the song cycle, though, because it is difficult to get singers to give time to new repertoire, and as a student I had absorbed Cage’s advice about never writing a piece without a performance prospect in mind. He had seen Adolph Weiss become bitter because he had produced so many scores that never got premiered, and he advised young composers not to fall into this trap. I took the advice perhaps too seriously, and have almost never written anything without setting up in advance the means of its performance. I’m changing my mind about this. If there’s anything I’m bitter about today, it might be the pieces I thought of writing and never did because no performance opportunity ever came up. Instead, when faced with a commissionless period I wrote only Disklavier pieces and electronic ones I could perform myself. I think I’m not going to limit myself this way anymore. After all, performances aren’t everything; they’re often disappointing (though the ones above are lovely), the recording doesn’t come out well, the critic doesn’t show up and if he does the reviews are stupid or meaningless, and I get sufficiently excited from hearing the music in my head and knowing what I’ve achieved. Anyway, I’ll be spending the first part of the summer writing a string quartet for which I do have a performance lined up, and afterward I’m thinking of embarking on some more quixotic projects. I may even set to music a few of those poems I never got around to.

I’ve always said that the optimum way to experience Nancarrow’s Player Piano Studies was “live” and close-up, being able to watch the piano roll go by. It’s a roller-coaster experience: you can see the notes coming before they get there, anticipate their crash into audibility a split-second before it comes, and it adds to the excitement. Well, Nancarrow’s piano technician Jürgen Hocker has put up You Tube videos of (almost) the complete Studies, including a couple outside the official canon (I say almost because I don’t see No. 41 yet, but perhaps it’s coming). The pieces are played on a pair of Bösendorfer grand player pianos, and it seems evident that Jürgen’s done something to the hammers to make them sound like Nancarrow’s altered pianos. Sometimes you get to watch the piano roll go by close-up; at other times the camera pans out so you can watch the keys play by themselves for awhile. It’s the next best thing to being down in that studio in Mexico City. Study No. 30, the “abandoned” one for prepared player piano, is included, though without the preparations (we could never quite figure out what they were); also Para Yoko, and an early study used in the Merce Cunningham dance from 1960, then withdrawn, which resurfaced decades later as Piece for Ligeti. Jürgen throws in many photo-explanations of Conlon’s working tools and method, so it’s an enlightening presentation, worth spending some time with. (Needs a robust browser, though, my Safari keeps blinking out on it.) (h/t Nick Seaver)

I’ve always said that the optimum way to experience Nancarrow’s Player Piano Studies was “live” and close-up, being able to watch the piano roll go by. It’s a roller-coaster experience: you can see the notes coming before they get there, anticipate their crash into audibility a split-second before it comes, and it adds to the excitement. Well, Nancarrow’s piano technician Jürgen Hocker has put up You Tube videos of (almost) the complete Studies, including a couple outside the official canon (I say almost because I don’t see No. 41 yet, but perhaps it’s coming). The pieces are played on a pair of Bösendorfer grand player pianos, and it seems evident that Jürgen’s done something to the hammers to make them sound like Nancarrow’s altered pianos. Sometimes you get to watch the piano roll go by close-up; at other times the camera pans out so you can watch the keys play by themselves for awhile. It’s the next best thing to being down in that studio in Mexico City. Study No. 30, the “abandoned” one for prepared player piano, is included, though without the preparations (we could never quite figure out what they were); also Para Yoko, and an early study used in the Merce Cunningham dance from 1960, then withdrawn, which resurfaced decades later as Piece for Ligeti. Jürgen throws in many photo-explanations of Conlon’s working tools and method, so it’s an enlightening presentation, worth spending some time with. (Needs a robust browser, though, my Safari keeps blinking out on it.) (h/t Nick Seaver) I’ve always said that the optimum way to experience Nancarrow’s Player Piano Studies was “live” and close-up, being able to watch the piano roll go by. It’s a roller-coaster experience: you can see the notes coming before they get there, anticipate their crash into audibility a split-second before it comes, and it adds to the excitement. Well, Nancarrow’s piano technician Jürgen Hocker has put up You Tube videos of (almost) the complete Studies, including a couple outside the official canon (I say almost because I don’t see No. 41 yet, but perhaps it’s coming). The pieces are played on a pair of Bösendorfer grand player pianos, and it seems evident that Jürgen’s done something to the hammers to make them sound like Nancarrow’s altered pianos. Sometimes you get to watch the piano roll go by close-up; at other times the camera pans out so you can watch the keys play by themselves for awhile. It’s the next best thing to being down in that studio in Mexico City. Study No. 30, the “abandoned” one for prepared player piano, is included, though without the preparations (we could never quite figure out what they were); also Para Yoko, and an early study used in the Merce Cunningham dance from 1960, then withdrawn, which resurfaced decades later as Piece for Ligeti. Jürgen throws in many photo-explanations of Conlon’s working tools and method, so it’s an enlightening presentation, worth spending some time with. (Needs a robust browser, though, my Safari keeps blinking out on it.) (h/t Nick Seaver)

I’ve always said that the optimum way to experience Nancarrow’s Player Piano Studies was “live” and close-up, being able to watch the piano roll go by. It’s a roller-coaster experience: you can see the notes coming before they get there, anticipate their crash into audibility a split-second before it comes, and it adds to the excitement. Well, Nancarrow’s piano technician Jürgen Hocker has put up You Tube videos of (almost) the complete Studies, including a couple outside the official canon (I say almost because I don’t see No. 41 yet, but perhaps it’s coming). The pieces are played on a pair of Bösendorfer grand player pianos, and it seems evident that Jürgen’s done something to the hammers to make them sound like Nancarrow’s altered pianos. Sometimes you get to watch the piano roll go by close-up; at other times the camera pans out so you can watch the keys play by themselves for awhile. It’s the next best thing to being down in that studio in Mexico City. Study No. 30, the “abandoned” one for prepared player piano, is included, though without the preparations (we could never quite figure out what they were); also Para Yoko, and an early study used in the Merce Cunningham dance from 1960, then withdrawn, which resurfaced decades later as Piece for Ligeti. Jürgen throws in many photo-explanations of Conlon’s working tools and method, so it’s an enlightening presentation, worth spending some time with. (Needs a robust browser, though, my Safari keeps blinking out on it.) (h/t Nick Seaver)