One sentence in Essays Before a Sonata has already cost me more time and trouble, I think, than the entire sonata:

“And there sits the little old spinet piano Sophia Thoreau gave to the Alcott children, on which Beth played the old Scotch airs, and played at the Fifth Symphony.”

The full paragraph sounds as though Ives is describing Orchard House in Concord, Mass., after a visit there, which is entirely plausible; Orchard House opened to the public as a museum in 1912, Ives wrote the essays in 1919, and he and Harmony liked to visit Concord. But I can find no evidence that Sophia Thoreau ever gave the Alcotts a piano. We know from Edward Emerson’s much later article about Thoreau that the Thoreau family scrimped and saved to buy a piano so that Henry’s sisters, Sophia and Helen, could learn to play. It seems doubtful that Sophia was ever in a position to give away a spinet, and there’s simply no record of it. The Thoreau scholars are mystified when I mention it. The first mention of Sophia in almost any Alcott biography is in 1877, when Anna and Louisa May bought the Thoreau house from her.

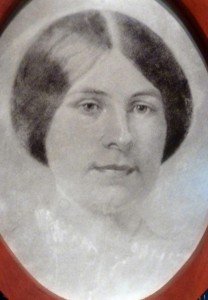

Of course, Beth in Little Women was based on Louisa May’s sister Elizabeth (pictured), called Lizzy (and spelled that way in family correspondence, which I’ve been reading in manuscript at Harvard’s Houghton Library). Beth is described as devoted to her piano. But while Little Women takes place entirely in a fictionalized Orchard House, the desperately poor Alcotts actually lived in twenty different places before finally achieving stability there in 1858, and poor Lizzy died a few months before they moved in. It’s difficult to imagine them carting a piano around. Moreover, in Orchard House today there is no spinet piano, and the staff there tells me there has never been one. Instead, there are a melodeon and a big square piano. Ives grew up with a square piano in his own house, and surely knew the difference between that and a spinet.

Of course, Beth in Little Women was based on Louisa May’s sister Elizabeth (pictured), called Lizzy (and spelled that way in family correspondence, which I’ve been reading in manuscript at Harvard’s Houghton Library). Beth is described as devoted to her piano. But while Little Women takes place entirely in a fictionalized Orchard House, the desperately poor Alcotts actually lived in twenty different places before finally achieving stability there in 1858, and poor Lizzy died a few months before they moved in. It’s difficult to imagine them carting a piano around. Moreover, in Orchard House today there is no spinet piano, and the staff there tells me there has never been one. Instead, there are a melodeon and a big square piano. Ives grew up with a square piano in his own house, and surely knew the difference between that and a spinet.

The Alcotts literature is maddeningly cavalier about occasionally referring to a nearby piano with no thought of explaining how they afforded one; the melodeon is never mentioned. The few facts I’ve been able to assemble are these, and keep in mind that Louisa May was born in 1832, Lizzy in 1835:

1843: The family is at Fruitlands, the badly thought-out Transcendentalist communal living colony. Louisa May writes in her journal, “Had a music lesson with Miss P. I hate her, she’s so fussy.” Miss P is Ann Page, the only woman at Fruitlands besides Mrs. Alcott. No mention of what musical instrument, if any, was involved.

July 24, 1846: Lizzy writes in her journal for 1846, the only year that survives: “I went to the post office. When I got home, Lydia Hosmer was here. I taught her a tune on the piano.” The family was then living at Hillside, which Hawthorne later bought and renamed The Wayside. (And by the way, the Alcott children’s journals are a real hoot. “Did my spelling lessons yesterday, and some long division. Mr. Emerson and Miss Fuller came by to see father. Today Mr. Thoreau took us daisy-collecting.” Geez, kids, name-drop much?!)

1852: Manufacture date of the melodeon.

c. 1855: Unitarian minister Henry Whitney Bellows takes a liking to “the twenty-year-old Lizzy” and gives her a piano, an incident that Louisa May will transpose to Mr. Lawrence in Little Women. This leads one to suppose, among other things, that the family no longer possessed the piano referred to in 1846.

1858: Lizzy dies while Orchard House is being renovated for the family to move in. The family is then given the square piano (manufacture date 1843) by “Auntie Bond,” Louisa Caroline Greenwood Bond, who was some kind of “foster sister” to their mother. The piano had belonged to Auntie Bond’s husband’s first wife, Sophia Bond; did Ives mix up these two Sophias? (The number of Sophias then living in Concord could have populated a good-size town by themselves.) Anna, the oldest sister, and Louisa May are written about as having played it.

1868: Louisa May writes Little Women. She depicts Laurie Lawrence, the love-interest, drowning his sorrows after Jo refuses his proposal of marriage in an angry performance of the Pathetique Sonata, presumably Beethoven’s. The sole mention of Beethoven by name is of a bust of that composer in a room in Vienna in which Laurie is trying to forget Jo by (and I find this rather unintentionally humorous) writing an opera.

The only volumes of music listed among Bronson Alcott’s books in Houghton Library are a few Italian operas. No Beethoven. That Beth/Lizzy may have played some Scottish tunes seems like a reasonable conjecture, but the only reference I’ve been able to unearth as to the kind of music the girls played is a folk song harmonized by Weber that Louisa May mentions in her 1843 journal: “Hail, all hail, the merry month of May.” That Lizzy “played at” Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony I have always assumed was a flight of wild imagination on Ives’s part, more necessitated by the sonata’s program than inspiring it. Ives’s memory was notoriously unreliable and his quotations rarely accurate, but I can’t completely discount the possibility that he correctly reported something he was told at Orchard House, something that might have been known by family friends at the time, but that no one has ever bothered to document in the subsequent literature; or perhaps his tour guide was herself misled. I am sorely tempted to forge, in neat, feminine handwriting, the following letter and slip it in among the Alcott archives:

Dear Louisa,

Today I had a rollicking good time ripping through the Kalkbrenner piano transcription of Beethoven’s Fifth on the old spinet Sophie gave us, the score of which I then burned to make sure it didn’t end up among daddy’s papers at Harvard. MWA-ha-ha-ha-ha-ha-ha-ha-ha-ha-ha!!!

Your crazy sister,

Lizzy

Meanwhile, hundreds of program-note writers for the Concord have taken Ives’s little story at face value. Personally, I wouldn’t. If you know of any relevant information, please contribute.