Via pianist Andy Lee and David McIntire’s Irritable Hedgehog record label, Dennis Johnson’s November is taking its place in the repertoire. Andy is giving the five-hour, 1959 piano work its European premiere at Cafe Oto in London on March 9 (and I’m thrilled to see that he’s playing music by the greatly underrated Paul Epstein there the previous evening). Then he’ll give the New York premiere at Issue Project Room on March 16, starting at 2. And Andy’s absolutely lovely four-disc recording, which I’ve been enjoying mp3s of, is now available, with my liner notes (which you can read in their entirety at the link). This definitely changes our picture of the history of minimalism – it will be difficult for anyone ever again to refer to Reich, Glass, and Riley as three of “the original minimalists.”

Via pianist Andy Lee and David McIntire’s Irritable Hedgehog record label, Dennis Johnson’s November is taking its place in the repertoire. Andy is giving the five-hour, 1959 piano work its European premiere at Cafe Oto in London on March 9 (and I’m thrilled to see that he’s playing music by the greatly underrated Paul Epstein there the previous evening). Then he’ll give the New York premiere at Issue Project Room on March 16, starting at 2. And Andy’s absolutely lovely four-disc recording, which I’ve been enjoying mp3s of, is now available, with my liner notes (which you can read in their entirety at the link). This definitely changes our picture of the history of minimalism – it will be difficult for anyone ever again to refer to Reich, Glass, and Riley as three of “the original minimalists.”

When Keys Collide

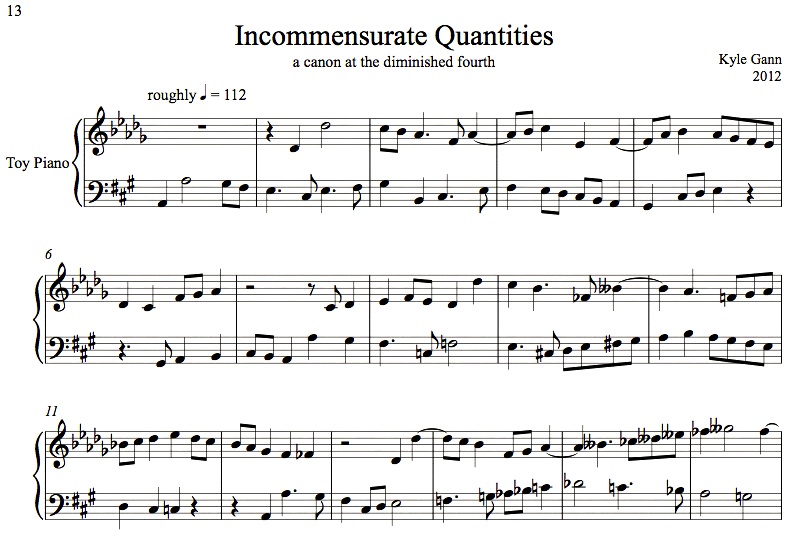

I’m rather obsessed with bitonality at the moment, and the three composers who are much on my mind and stereo lately – Charles Ives, Kaikhosru Sorabji, and Darius Milhaud – all have a strong bitonal streak in their music, though that’s not as well known about the first two as it is about Milhaud, who wrote a book on bitonality. My wife Nancy gave me a three-octave toy piano for my recent birthday, and as a kind of sketchbook I wrote a suite for it called Surrealities; of the seven movements, two are atonal, one tonal, three bitonal, and one bi-modal (C harmonic minor in one hand, C Lydian in the other). I’m particularly pleased with the sixth movement, “Incommensurate Quantities,” which is a bitonal canon in A and D-flat, the only canon I know of at the interval of a diminished fourth. More to the point, it follows all the traditional contrapuntal rules, resolving every dissonance correctly, and of course contains an episode in the equidistant key of F (Gbb):

You can hear me play it here. Also another bitonal movement “Deep Denial” (A in one hand, C alternating with F# in the other), and the last (tonal) movement “Mistimed Adieu,” which I’m quite happy with.

In my youth Milhaud was one of my favorite composers, and he’s never quit being, though one doesn’t encounter his name much these days, or get opportunities to write about him. When I last visited San Francisco, Richard Friedman reminded me of a wonderful Milhaud piece I remember well from the 1960s, recorded only on vinyl, called A Frenchman in New York, written to go on the flip side of Gershwin’s American in Paris – and the Milhaud is by far the better work. To allow you to assess that judgment, I temporarily upload the recording he gave me here. I hadn’t heard it in thirty-five years, and with the first notes it all came flooding back from the recesses of my memory. Philip Glass has told me that Milhaud is one of his ongoing influences as well.

Unanticipated Perks of Scholarship

This Thursday I will escape this long frigid spell we’ve been having in the northeast – to go to Miami! Where I will give a talk on John Cage’s 4’33”, at 6:30 Thursday evening, to open the New World Symphony’s John Cage festival, which lasts through the 10th. And I’m staying down there for it. Beachfront hotel, smoke a few cigars with my friend Mikel Rouse who’s down there doing an installation, sit on the beach, high near 80 degrees every day. If this is what musicology can get me in my old age, I’ll take it. I’ve been thinking lately, these are terrible times to be a composer, but pretty damn good times to be a musicologist.

This Thursday I will escape this long frigid spell we’ve been having in the northeast – to go to Miami! Where I will give a talk on John Cage’s 4’33”, at 6:30 Thursday evening, to open the New World Symphony’s John Cage festival, which lasts through the 10th. And I’m staying down there for it. Beachfront hotel, smoke a few cigars with my friend Mikel Rouse who’s down there doing an installation, sit on the beach, high near 80 degrees every day. If this is what musicology can get me in my old age, I’ll take it. I’ve been thinking lately, these are terrible times to be a composer, but pretty damn good times to be a musicologist.

A Video of Nothing

Microtonal pianist Aron Kallay alerts me to a YouTube video of him playing part of the “Nothing” movement from my Echoes of Nothing. The full movement is a few minutes longer (and, there’s kind of a superfluous one-minute intro to this five-minute video).

An Avant-Gardist Anticipated

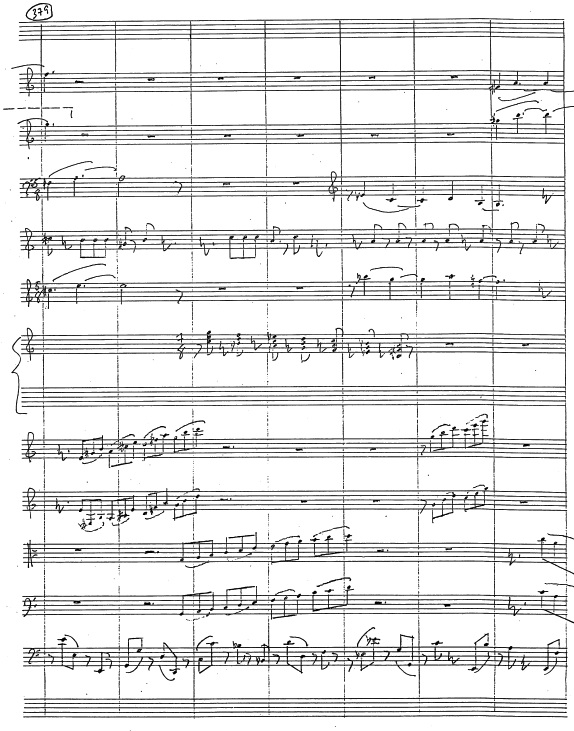

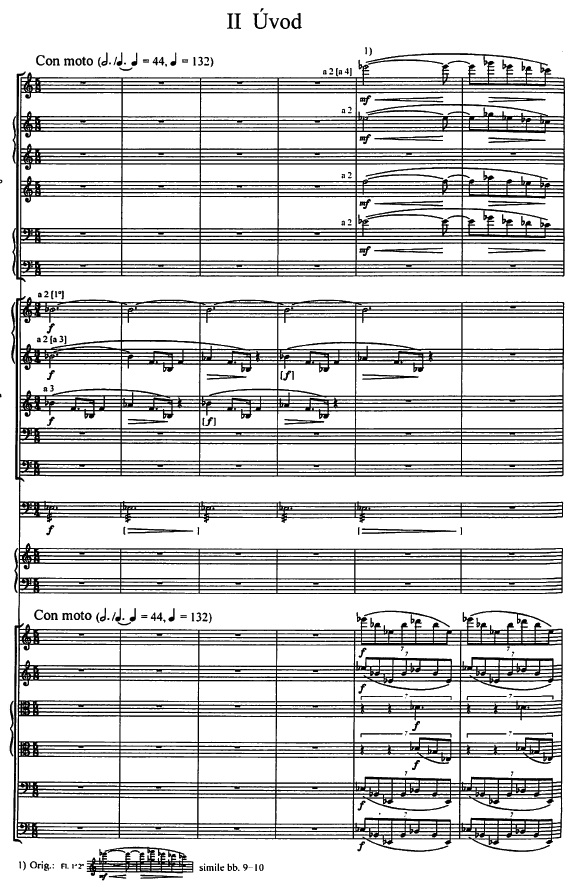

Below is a page from Conlon Nancarrow’s Piece No. 2 for Small Orchestra of 1986. If it is sufficiently readable here, you may be able to see that the different instruments are in three meters at once: some in 5/8, some in 6/8, and some in 7/8. Very difficult to play convincingly, because part of the orchestra will be playing every fourth 8th-note in the 7/8 while others are playing every third 8th-note in 5/8, and so on. The conductor gives the downbeat of each measure, and the poor sods have to fit their 5 or 7 into it as best they can:

A couple of weeks ago in Amsterdam I made my usual pilgrimage to Broekmans & Van Poppel, one of the world’s great music stores and a place I can spend hours browsing in. There are always a few composers on my horizon with whose work I keep meaning to become more familiar, and Leos Janacek is one of them lately. So I happened to pick up the Glagolitic Mass (1926), and bought it – because in the second movement I was startled to find the exact same set of simultaneous meters Nancarrow uses above:

The brass is notated in 3/4, and the winds and strings in 5/8, though the strings have to play a septuplet across the 5/8; and these rhythms continue in poly-tempo profusion throughout the movement. Of course I think it highly unlikely that Nancarrow ever saw a score to Janacek’s Glagolitic Mass (I had actually heard the piece in high school, but it’s difficult to register a bizarre effect like this if you’re not expecting anything of the kind). Had Conlon seen it, I think it more likely that he would have avoided using a rhythmic setup Janacek had already used six decades earlier. What an extraordinary coincidence – and how much credit I will have to give Janacek from now on for his precedence.

The brass is notated in 3/4, and the winds and strings in 5/8, though the strings have to play a septuplet across the 5/8; and these rhythms continue in poly-tempo profusion throughout the movement. Of course I think it highly unlikely that Nancarrow ever saw a score to Janacek’s Glagolitic Mass (I had actually heard the piece in high school, but it’s difficult to register a bizarre effect like this if you’re not expecting anything of the kind). Had Conlon seen it, I think it more likely that he would have avoided using a rhythmic setup Janacek had already used six decades earlier. What an extraordinary coincidence – and how much credit I will have to give Janacek from now on for his precedence.

UPDATE: Let me add: the main thing that’s kept me from getting as familiar with Janacek as I’d like to be is the difficulty of finding English translations of his opera libretti. Anyone know a way around that one, let me know.

Oops, Too Late

Apparently the Utrecht Wind Ensemble played the second movement of my piano concerto Sunken City in Utrecht at their concert of last Saturday night, along with works by Stravinsky, Donnacha Dennehy and others:

I remember they had contacted me about the possibility several months ago, but hadn’t heard anything more. They have a short audio clip at their general web site. Don’t know why only one movement, but it’s the “serious” one.

Earle Brown in Shifting Perspectives

My old friend Tony DeRitis, composer and chair of music at Northeastern University, took the above nice photo of me and Carolyn Brown at that school’s Earle Brown symposium over the weekend. Long-time Merce Cunningham dancer and Earle’s first wife, Carolyn was making some meltingly gratifying comments about my 4’33” book. The previous day she had publicly presented a touchingly personal story of her life with Earle: he had fallen in love with her at age 12 (she was 11) in Lunenberg, Mass., where she was his best friend’s sister. Carolyn’s parents practically adopted Earle, took him along on vacations, and in his late years Earle said that if it hadn’t been for Carolyn’s mother (herself a dance teacher), he would never have become a composer. So we got his bio from 1939 on, from an eye witness. Never heard another composer’s life story anything like it.

And the story that emerged of Earle Brown’s music was equally fascinating. The second wife, Susan Sollins-Brown (and it dazzled everyone having a conference about a dead composer with both his wives present), has set up an amazingly efficient archive of the complete works and sketches, and scholars are flocking to it. I will post my keynote address on the subject somewhere in the near future, but the short version is that Brown’s music is far more intricately structured than most of us knew about, and that the Schillinger-style thinking is evident everywhere. Unlike his friends Cage, Feldman, and Wolff, he’s very analyzable.

I do have to make one gripe about the musicology community in general, and perhaps it won’t fall on deaf ears. Scholars seem to get endlessly fascinated by the early, simple, seminal works of innovative composers, and dwell on them even when they’re not very interesting in themselves. In Earle Brown’s case it was the graphic score December 1952, which we heard way too many performances of and far too much about. Sure, it was an important breakthrough piece for Earle, but it was important because it eventually enabled him to write much better, more interesting works much later. Same thing goes, at other conferences, for Steve Reich’s It’s Gonna Rain, La Monte Young’s “Draw a straight line and follow it,” and Feldman’s early graph paper pieces. Those pieces aren’t fantastic because they’re fantastic, they’re interesting because those composers went on to do infinitely more beautiful things later, and to study those ad infinitum at the expense of the great later pieces is a recipe for dullness. Perhaps I am similarly guilty in having written a book on 4’33”, but that’s what I was asked to write about, and you’ll never find me saying it’s one of my favorite Cage pieces (much rather listen to the String Quartet in Four Parts, In a Landscape, Hymnkus, Sonatas and Interludes, Europeras, 74).

So it got so I had to walk out whenever December 1952 was trotted out again (even Earle resented the overemphasis on it during his lifetime). But as compensation we heard sparkling performances by the Callithumpian Consort of Available Forms I and Sign Sounds, two middle-period pieces I’d never heard, and wonderful, sketch-oriented analyses of Cross Sections and Color Fields by Frederick Gifford and of the Calder Piece by Elizabeth Hoover. I’ll be glad to hear Brown’s pre-1961 music again someday when performances of his exhilarating mature music have become so common that a little perspective would be nice.

An Improvising Conductor Gets His Due

Friday morning at Northeastern University in Boston, I’ll be giving the keynote address for Beyond Notation: An Earle Brown Symposium. Though I’d met him a few times, Brown is someone whose music I had never studied in detail, and it’s been revelatory getting to know it better. Just hope I come up with something insightful to say, because the experts start talking after I finish.

Friday morning at Northeastern University in Boston, I’ll be giving the keynote address for Beyond Notation: An Earle Brown Symposium. Though I’d met him a few times, Brown is someone whose music I had never studied in detail, and it’s been revelatory getting to know it better. Just hope I come up with something insightful to say, because the experts start talking after I finish.

Glass, Potter, Gann in Amsterdam

Glass as Romantic (1981-Style)

I’m back from the Einstein on the Beach festivities in Amsterdam, and Friday at 3 I’ll be giving a reading from my 4’33” book at the National Academy Museum in New York City. [No, I won’t stand there without saying anything. Ha-ha.]

UPDATE: You can ignore the following. Frank Oteri wants to put my Einstein analysis on New Music Box, where it will reach a wider audience. Going commercial, at whatever modest level, is always better than going academic when you have the chance, if you can do so without compromises. So I’ve pulled the article off my website, and will announce when it’s on NMBx.

As for my paper on Einstein, I decided for now not to blog it, but to put it up on my web site, so you’ll find “Intuition and Algorithm in Einstein on the Beach” there. I’ve seen a lot of scholars post scholarly articles on their web sites, and it strikes me that it carries just a touch more gravitas than doing it on one’s blog. It would be nice to have it in a journal somewhere and be an official Phil Glass scholar, but it’s kind of an empty credential to play off against the advantage of people finding it easily on Google. As I’ve said before, I’m all for peer-review in principle, but it’s kind of a double-edged sword. The purpose of peer review is to make everyone conform, meaning 1. making everyone conform to the facts, which is great, and I’m happy to be fact-checked and have typos caught; and 2. making everyone conform to the conventions of academic writing, which can be deadly awful. Depending what “peers” review me (and while thousands of people write as well as or better than I do, only a handful of them are musicologists), I am likely to be told not to be so breezy, casual, and journalistic, and that I ought to be more interpretive, and properly mention Deleuze, and throw in some critical theory, and all that crap. I really think that after one’s published a certain number of books from academic presses (let’s just say five, for the sake of argument) one should get a permanent free pass from peer-review, and have one’s writings accepted verbatim thereafter. But, that’s what the internet’s for, right? The masses will, in time, catch my miscalculations and typos. I can’t quite believe that no one else has yet compared the two Dances in Einstein, but I couldn’t find it elsewhere, and perhaps someone will bring such a case to my attention. If not, now it’s been done.

UPDATE: And I’ve been remiss in not thanking Juhani Nuorvala for the nice Tom Johnson quote, which I used prominently.

Ambient Caroling

My friend George is looking forward to a respite from Cage performances now that the centennial is ending. He says it got so bad he couldn’t even enjoy “Silent Night” anymore.

Graphing Glass

A week from today and tomorrow, I’ll be in Amsterdam for the University of Amsterdam’s conference on Phil Glass’s Einstein on the Beach. I’m taking part in a panel discussion January 5, and on the morning of the 6th I’ll give a paper on my analysis of Einstein, the writing of which I am interrupting briefly to make this announcement. My interest is in the intuitive and nonlinear (right-brain) structuring of the piece’s music, which was such a departure from the process-oriented minimalism of previous years. In fact, while it’s easy to see what’s going on in the music, it’s cost me considerable thought and some ingenuity to figure out how to describe it or chart it in some clear way. For each movement (scene) I’m trying to come up with a concise graphic that will encapsulate the relevant details.

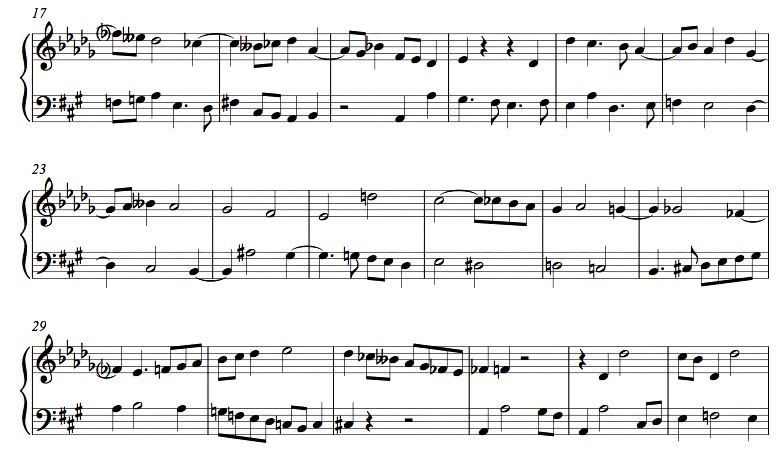

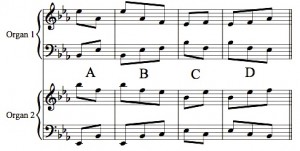

For instance, the “Building” scene is a really simple continuum of eighth-notes for two organs in a pentatonic scale, something like Music in Contrary Motion. But the musical logic is not at all linear, and is difficult to spell out. I finally realized that the music can be reduced to four modules:

Of course, the fact that module A is included in module B, and C in D, is part of the apparent micro-complexity. But I figured out I could line up all the repetitive patterns in such a way that one can tell instantly what changes from one pattern to the next (each pattern in repeat signs represented here by one line):

What logic there is becomes evident, I think. The piece begins with the two 3/8 modules (B and D), and in the first half inserts module A in various and changing places. Unlike earlier pieces such as Music in Fifths, the process isn’t additive, but sometimes jumps the added module from one place in the pattern to another. The first half expands with added A’s and then contracts down to just B and D again, and then starts adding in module A at the beginning, and introducing module C toward the end, of each repetition. Then A drops out and it concentrates on BCD for awhile, gradually moving toward an emphasis on the 10/8 pattern ABCD before reducing back to BD at the end. Of course, what one hears are mostly the irregular rhythmic accents made by the highest and lowest repeating notes.

This being a rather formal paper, I once again have the decision to make as to whether to submit it to an academic journal or just publish it here. I like the journal American Music, and have connections with it, but its articles aren’t always accessible on JSTOR, and access is the whole point. Musical Quarterly is terribly slow, taking years between submission and publication. Perspectives of New Music was the prestige music journal of my youth, but while they might publish it for variety’s sake, the editors really seem antipathetic to this kind of music; they tried to slightly sabotage my Well-Tuned Piano article 20 years ago, and I’ve never been tempted to send them anything else. So I have to weigh whether having another résumé line is worth limiting the article’s circulation. Meanwhile, I get a trip to Amsterdam out of it, and there are few places I love more.

The Untold Tale

People are telling me they’ve received their copies of my Robert Ashley book from Amazon. (I still have only one myself.)

There’s one story Bob told me that I didn’t include in the book, just because a scholarly book like this didn’t seem the right place for it. (Well, there are several stories, but one he didn’t ask me to keep to myself.) When Bob was a toddler his mother and grandmother were giving him a bath in the sink, and he managed to stick his finger into an empty electrical socket. He lost consciousness and they frantically tried to bring him back. He watched the whole scene, he remembers, from above them in the kitchen. He came to, and ever since he’s believed in the soul’s ability to leave the body.