Displaced quintuplets in apparent 4/4 meter, from my new piece Sang Plato’s Ghost (click for better focus):

Kyle Gann on music after the fact

Today at a local hangout I met Hudson Valley composer Brian Dewan. I knew the name. We got to talking, and he mentioned a composition teacher of his who had enlarged his view of modern repertoire. Idly curious, I asked who it was. “Joe Wood,” he replied.

I think my glass of wine hit the bar with a thud. “Joe?! Wood?! You went to Oberlin?”

He had, eight years after I did. Joseph Wood (1915-2000) was a composer who had come mainly from the commercial music world. Wikipedia credits him with an arrangement of “Chiquita Banana” for Xavier Cugat, a career in Muzak arrangements, and the choral writing for the musical Brigadoon. Yet he had a 1950 orchestra piece, simply called Poem for Orchestra, on a CRI record. He was my first composition teacher in college, and taught the only orchestration class I ever took. As Brian and I both remembered, he was looked down upon by the hot-shot Oberlin comp students as an old fogey, but we each thought of him as a kindly gentleman. There was a persistent rumor that he had written the Looney-Toons cartoon theme. I never quite believed it, and Brian had actually asked him if it was true. He said Joe looked off into the distance for a long moment and replied with some melancholy, “I never did that.” His taste did seem quite wide-ranging considering his personal Romantic aesthetic; I remember being assigned to orchestrate an early Stockhausen klavierstück, though I can’t imagine what the criteria of success would have been. Brian remembered him praising Ligeti as someone who had never written a bad piece.

Joe Wood gave me what was, for its timing, one of the most comforting compliments I have ever received. We were at the Midwest Composers Symposium in Iowa or some godforsaken place, and ended up walking back together after a concert. He was complaining about some horrible piece we had just heard. The previous evening, I had had a piece played that was a godawful improvisatory graphic score filled with theatrical silliness. Pausing after his diatribe, Joe said, by way of contrast, “Your piece was young, but it had talent.” To say my piece was young was an understatement; it was pompously puerile. To say it showed talent was an outright lie; whatever talent I have, that youthful experiment did not reveal. But for him to say that to a freshman conferred a touching dignity upon me at a time in my life in which dignity was still an unfamiliar thrill. I have not heard his name often in the intervening years, but when I have I have always conferred a reflexive blessing upon it.

I am listening to Poem for Orchestra as I write; I digitized it a few years ago for old time’s sake, and keep it on my hard drive. And I drink a toast tonight to a composer mostly forgotten now, but one whom two former students could think of fondly decades after he gently touched their lives.

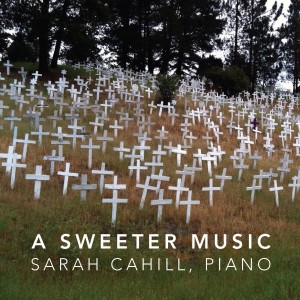

I am in receipt, today, of a few copies of pianist Sarah Cahill’s new compact disc on the Other Minds label, A Sweeter Music. It’s a compilation of eight pieces from her project commissioning composers to write music that protests war and urges peace – out just in time for our Nobel-winning president to bomb the hell out of Syria. On it Sarah plays (and speaks) my War Is Just a Racket, on a 1933 speech by General Smedley Butler, along with other pieces by Terry Riley, Meredith Monk, Frederic Rzewski, Carl Stone, Phil Kline, Yoko Ono, and the Residents. There’s a lot of sensuously beautiful stuff on this disc; my piece and the Residents’ are the only ones to use text. Sarah does a magnificent job, as always, and will be recording the other ten pieces from the collection at a future date.

I am in receipt, today, of a few copies of pianist Sarah Cahill’s new compact disc on the Other Minds label, A Sweeter Music. It’s a compilation of eight pieces from her project commissioning composers to write music that protests war and urges peace – out just in time for our Nobel-winning president to bomb the hell out of Syria. On it Sarah plays (and speaks) my War Is Just a Racket, on a 1933 speech by General Smedley Butler, along with other pieces by Terry Riley, Meredith Monk, Frederic Rzewski, Carl Stone, Phil Kline, Yoko Ono, and the Residents. There’s a lot of sensuously beautiful stuff on this disc; my piece and the Residents’ are the only ones to use text. Sarah does a magnificent job, as always, and will be recording the other ten pieces from the collection at a future date.

Why are good teachers strange, uncool, offbeat?

Because really good teaching is not about seeing the world the way that everyone else does. Teaching is about being what people are now prone to call counterintuitive, but to the teacher simply means being honest.

– Mark Edmundson, Why Teach?: In Defense of a Real Education, p. 181

At the request of my department chair – and he so rarely asks me for anything, I could hardly have turned him down – I am teaching a 20th-century music history survey course, or rather, music since 1910. I’ve been dreading it, and my fears are so far confirmed. First of all, I have long been convinced that you can’t do the entire 20th century in a survey course. To me, third-semester music history should be 1900-1960, and the fourth semester should take over after that. Not only is there way too much material, there’s no unifying idea to the first and second halves of the century. The year 1976 seems to remain a popular stopping point for many professors and textbooks, and I wonder if anyone (besides me) has ever taught a 20th-century class in which the last three decades got as much attention as the first three.

Secondly, while it’s always easy to know where to start, and has always been tricky knowing where to end, these days ending is impossible. Forty years ago, when I took this course at Oberlin, you could begin with Stravinsky and Schoenberg and work your way up, decade by decade, through the various movements and major figures. It was assumed that the language of music was evolving, and that that evolution could be traced, with a few detours and parallel streams. But of course, now we know what happens: past 1970 the idea of a mainstream evaporates, and – as musicologist Leonard Meyer so shrewdly predicted – we entered a kind of stasis in which many, many styles compete and continue. Everything is permissible; a million things have been done, anything we can imagine will be done eventually, and many things that had been done get done all over again. I suppose if you’re a hard-core traditionalist it’s easier to draw your boundaries, but the Downtown music I like to focus on blends into jazz and pop around the edges. I have to argue with students for the right to teach Laurie Anderson, Pamela Z, and Mikel Rouse as postclassical music. Just deciding what music to include within the definitions of the course requires a whole separate section on the philosophy of music.

And I am finding that the philosophical difficulties extend into the past retroactively. I know perfectly well what I’m supposed to teach, and in fact, I am quite lucky in my mandated choice of textbook: the new Taruskin/Gibbs Oxford History of Western Music. The book itself has revisionist leanings and casts its own sly suspicions on orthodox pedagogy, and so is more in sync with me than any other textbook I could use. The best thing I can say about it is that its pronouncements never make me wince, which I consider high praise in this context. We use it for the entire music history sequence because its quality is so high; the fact that Professor Gibbs is on our faculty is, of course, entirely coincidental (as is the fact that I am heavily quoted in the final chapter).

But given the sequence of the textbook, I have to start out with Schoenberg, and for me, to start with Schoenberg already puts everything on the wrong track. (If this offends you, read further at your own risk, because it’s only downhill from here.) The assumption of Schoenberg’s importance, given the continuing unpopularity of his music, is founded on the further assumption that what we’re teaching is the evolution of the musical language. In fact, the very title of our music history sequence, The Literature and Language of Music (“lit’n’lang” in departmental parlance, reminding me of “live ‘n’ learn”) presupposes that there is a language of music evolving through its canonical examples. If you want to trace a certain absolutist attitude toward atonality, and the development of the 12-tone row as a technical device, Schoenberg is of course essential to the sequence of events. But does his music, therefore, deserve pride of place in the literature?

I consider it the most important thing I can teach my students, assuming I ever succeed in getting it across, that a lot of music that seems nonsensical or off-putting at first is well worth putting the effort into assimilating. Nothing irks me more than the reflexive resistance they put up against music they don’t “like” on first listening. When I was their age, any piece I didn’t understand represented a challenge, a gauntlet thrown down to my musical intelligence. There was not going to be any piece I couldn’t fathom. (Many fine “conservative” pieces I could superficially comprehend, I now realize I dismissed rather too easily.) And yet, there is now tons and tons of difficult, complicated, obscure music, and after 45 years of deciphering it I am aware that not all of it eventually repays the effort. I was determined to master the intricacies of the Concord Sonata, Le Sacre du Printemps, Pli selon pli, Turangalila, Mantra, Philomel, and I love them all, I’m devoted to them, thrilled to introduce students to them. Other works that I committed many, many listening and analytical hours to – almost all of Schoenberg, everything by Berg except Wozzeck, all but a few pieces of Elliott Carter – simply bore me today. I know that Op. 31 Orchestra Variations and that damn “Es ist genug” violin concerto inside and out, but they strike me as awkward and pedantic. I listen to them with acute understanding of how they’re made, but never admiringly. A lot of that music I feel I was brainwashed into taking very seriously, and the effects of my youthful brainwashing are largely worn off.

So, of the music I cannot honestly advocate to students on account of what I perceive as its inherent virtues, by what criterion do I urge it on them? If historical importance is the guideline, then one needs to climb the ladder of influences, but it turns out that that ladder frays into a maze at the top. And actually, looking back from 1970, any sense of a mainstream had pretty much died as soon as neoclassicism was pitted against dodecaphony. The moment Scriabin, Ives, Stravinsky, Varése all separately agreed to use sonorities never heard in music before, everything really became permissible instantly – it just took a few generations to realize the implications. People today still write neoclassic music, still write 12-tone music. Partch leaped into just intonation only 15 years after The Rite of Spring, seven years after the first 12-tone row, and that’s the course I’m still on. 4’33” is closer in time to Pierrot Lunaire than it is to the present. If we’ve had a hundred years of multi-subcultural stasis, how much does it really matter who did something first? My students get a much bigger kick out of Gruppen and Sinfonia than they do from Webern, and since I agree with them, why not simply detail the pedigree of the 12-tone idea as part of a discussion of serialism? Why play the first 12-tone music instead of the most rewarding?

In fact, to present 12-tone music as a major movement at all, I have to attempt to explain why certain composers considered it so crucial to have some universal new system to replace tonality. And the truth is, I don’t understand why they felt that way. I’m so much more in sympathy with what Ives wrote: “Why tonality as such should be thrown out for good, I can’t see. Why it should always be present, I can’t see.” Tonality is so widely evident in much well-regarded music of recent decades that my students and I share the same incomprehension on this point. It sounds like an episode that belongs in the book Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds. Some people in my position would make a countercharge about minimalism, but they would have to contend with the Steve Reich and Arvo Pärt fans among my students; and minimalism never tried to corner the market. (I’m also teaching my minimalism seminar this semester, and the students in there are passionate about the subject, so well-informed that they’ve brought up more obscure pieces than I had planned to address.)

The upshot is that I can no longer teach the canon of early/mid-20th-century music, as it was taught to me, in very good faith. The only criterion I could defend, if challenged, is how much fulfillment I still get from the music today, with some scholarly lip service granted to what pieces posed an influence on the composer’s contemporaries. Certain composers who don’t get much academic attention – Milhaud, Poulenc, Tailleferre, Busoni, Wolpe, Sorabji, James P. Johnson, Vermeulen, Blomdahl, Rochberg – seem to me infinitely more appealing to present than some of the usual suspects. After all, we’ve already gone through this revisionist process for 19th-century music: if we hadn’t, we’d still have to be putting Hummel and Spohr on the listening tests. At the other end, I have only the flimsiest of rationales for teaching all the wonderful array of postclassical music I love while still excluding jazz and pop, the ultimate one being my faulty or nonexistent expertise in those latter fields. I resorted to describing the history of my idiosyncratic career as justification for my particular view of recent history, and while I’m happy for student input, I hardly want to surrender my hard-earned historical understanding to the chaos of 22 variously-informed student perspectives.

So it’s a mess, and an enforced experiment with few visible guideposts. I’m afraid I know the last hundred years of music so well that I no longer know what the history of it is.

I picked up Mark Edmundson’s book Why Teach?: In Defense of a Real Education because of a Times review that mentioned his complaint about a college culture in which professors give slim homework assignments in return for good course evaluations from students. Boy, did that strike a nerve. Those student evaluations carry enormous weight. I do well on them. I’m a pretty good song ‘n’ dance professor. I bring up episodes from The Simpsons to make a point. I slip quotations from The Big Lebowski into my lecture and glance around the room to see who perks up. I am famous for my digressions, and occasionally a student evaluation will even admit, “His stories go wildly off-topic, but somehow they end up being relevant and adding to the discussion.” I like to hear my jaw rattle, and when allowed a captive audience I can get a little manic (as a lot of people who know me socially would have trouble believing).

But you know what? At Northwestern I studied medieval music with Theodore Karp, a round little man with a distinct whisper and a slow, deliberate air. He had no song ‘n’ dance in him at all. Students beyond the front row could hardly hear him. Yet he knew every music manuscript of the 11th through 16th centuries top to bottom, and the calm, munificent way he dignified every student question, no matter how misguided, with a meticulous and carefully qualified reply, at whatever length necessary, made him a glowing presence. He was the Yoda of musicology. I was devoted to him, and after his 15th century class knew that period almost as well as the 20th century. As an undergrad I had an aesthetics professor, too, whose pause-studded lectures could cure insomnia, but we had great discussions in his office afterward. And the music theory teacher whose knowledge I most pass on to my own students today was distinctly lacking in charisma. As I look back, I was impressed by academics who could keep a class laughing, but there wasn’t much correlation between how clever a lecturer a professor was and how much impact he or she had on me. It had to do with something else – perhaps a dogged determination to impart knowledge.

As a result, when I sit on faculty evaluation committees, I’m the one who ends up defending the boring but expert professors, the ones who get poor write-ups from non-majors who just took the class for a distribution requirement, but whose senior project advisees think of them as gods. And I’m a little ashamed of myself for feeling smug about my ability to entertain 19-year-olds. Though perfectly successful by the available metrics, I am not yet the type of professor I most admire.

One of the problems with college culture throughout the field, I think, is that teaching well is not rewarded much. Everyone smiles indulgently when a student raves about a professor, but it’s publishing (mostly), committee work (somewhat less), and professional honors that raise one’s profile in the institution. I resent switching my focus from my current book project to my next class, partly because it’s the book that’s going to impress my superiors and colleagues. That’s kind of sad. Edmundson is exercised about college devolving into a credential factory, in which we entertain young people for four years and then declare them qualified for a job without having changed their lives, transforming their sense of who they are. He waxes eloquent on the way we present to them the great minds of the past condescendingly, without acknowledging how much superior they were to most of us today. My school recently lost a wonderful music teacher who had come from studying and teaching in Asia, and she was horrified by how lazy American students were. She wouldn’t bend on her assignment workload, and her student evaluations suffered as a result; now she’s teaching in Beijing, where she’s more justly appreciated.

I emphasize that my own school is not extreme in this regard; Edmundson makes it clear, with reports from colleagues at schools all over, that college culture is fairly uniform, and heavily conditioned by mass culture and the internet. I’ve adapted too well to this undemanding milieu, and I’m trying to figure what to do about it. I cut the kids too much slack because they are just like I was at that age: arrogant, fragile, neurotic, and affronted by criticism. They come in having had their self-esteem artificially pumped up in high school, and their expertise in certain things I know little about – technology, pop culture, stuff they’re read about on Wikipedia – is indeed impressive (as, Edmundson insists, our liberal relativism makes us all too quick to admit; wisdom has been reduced to knowledge, knowledge to information, and all information is equal). Yet they’re also personally insecure enough that to hammer them about their cultural ignorance, their inability to think critically, would feel cruel. As one of my more perceptive colleagues put it (who paid his own way through college), “I’m resigned to the fact that I’m going to spend my career patting rich people’s kids on the head.” In one respect, many of them are not like I was:Â I am miserably astonished at how few of them really want to take pride in how good a theory or history paper they can write. Outside their performance major, meeting the bare minimum requirements is too often good enough. As a writer myself I want to push and push them to express themselves clearly and dig beneath the obvious facts, but pressing them too hard goes against the culture, and they’re already insulted by a B-plus that I thought of as a gift.

I do not remember being nearly as focused on social life as kids seem to be today. Parties were a terrible trial for me, and I was little enough socialized that solitude was often preferable (and still is). I’m embarrassed today to recall how many classes I skipped, but I was constantly reading and studying for self-improvement. I remember reflecting that very little learning actually took place in classrooms (a self-fulfilling prophecy in my case), and that the main thing I could absorb from my music profs was their attitude, their jaunty disregard for things that didn’t matter and their laser focus on things that did. That does seem to work for some students (and I seem to be the perfect teacher for the lackadaisical hot-shots who were most like me), but it doesn’t work for them all.

On the other hand, Edmundson – several years older than I am – remembers a college culture in the 1960s that was different from the one I found. He had professors who challenged him, risked offending him, and changed the way he thought. I went to Oberlin in the ’70s, and things, if he is correct, had changed. With the rapid rise in student population in the ’60s, a slew of new young faculty got hired quickly. As I think back, many of them – even some of my favorites – seemed breathtakingly irresponsible. One of my professors spent an entire class reading us a crazy satire of musicology articles someone had written. He was brilliant, and tremendously entertaining. He was also the teacher who warned me that Cage was a charlatan and minimalism a scam, but I didn’t think him less brilliant for that, only limited in perspective. It was not uncommon, at the time, for professors to require almost no work at all. There was a war in Vietnam; guys who flunked would get snapped up by the draft board (actually that ended the month before I turned 18); and grade inflation was through the roof. My GPA was 3.78, and I’ve always sworn I was in the bottom half of my class. In other words, if American college culture has really gone so far downhill, it seems to have begun happening after Edmundson went to school, and before I did.

Perhaps unfortunately, I developed my teaching style in conscious imitation of some of those professors, but I don’t dare be as slipshod as some of them were; the climate has changed. Nevertheless, I’m going to try to see how much more I can push my students this year, without injuring their delicate self-esteem. The student evaluations can no longer concern me, because I’ve exhausted all the honors the school can bestow. As the old-timers tell me, I’ve only got two promotions left: “emeritus” and “dead.” Unlike my more vulnerable younger colleagues, I no longer need the students to be my friends. I’m three times their age now, and I’d much rather they astonish me with their commitment, enthusiasms, and bursts of originality. Their lack of intellectual ambition is a perennial disappointment, and I’m going to try to focus on changing that, if I possibly can, rather than on keeping them entertained. I may even have to become boring.

From Mark Edmundson’s Why Teach?: In Defense of a Real Education:

It’s his capacity for enthusiasm that sets [a favorite student he has described] apart from what I’ve come to think of as the reigning generational style. Whether the students are fraternity/sorority types, grunge aficionados, piercers/tattooers, black or white, rich or middle class… they are, nearly across the board, very, very self-contained. On good days they display a light, appealing glow; on bad days, shuffling disgruntlement. But there’s little fire, little passion to be found.

This point came home to me a few weeks ago when I was wandering across the university grounds. There, beneath a classically cast portico, were two students, male and female, having a rip-roaring argument. They were incensed, bellowing at each other, headstrong, confident, and wild. It struck me how rarely I see this kind of full-out feeling in students anymore. Strong emotional display is forbidden. When conflicts arise, it’s generally understood that one of the parties will say something sarcastically propitiating (“Whatever” often does it) and slouch away.

How did my students reach this peculiar state in which all passion seems to be spent? I think that many of them have imbibed their sense of self from consumer culture in general and from the tube in particular. They’re the progeny of a hundred cable channels and videos on demand. TV, Marshall McLuhan famously said, is a cool medium. Those who play best on it are low-key and nonassertive; they blend in. Enthusiasm… quickly looks absurd. The form of character that’s most appealing on TV is calmly self-interested though never greedy, attuned to the conventions, and ironic. Judicious timing is preferred to sudden self-assertion….

Most of my students seem desperate to blend in, to look right, not to make a spectacle of themselves. (Do I have to tell you that those two students having the argument under the portico turned out to be acting in a role-playing game?) The specter of the uncool creates a subtle tyranny. It’s apparently an easy standard to subscribe to, this Letterman-like, Tarantino-inflected cool, but once committed to it, you discover that matters are rather different. You’re inhibited from showing emotion, stifled from trying to achieve anything original. You’re made to feel that even the slightest departure from the reigning code will get you genially ostracized. This is a culture tensely committed to a laid-back norm. (pp. 7-9)

I wouldn’t try to vouch for how aptly this description applies to student culture today in general; I try never to assume that Bard is typical. But it certainly explains to me for the first time why so many young composers hold it against me that I took an outspoken part in the serialism-minimalism feud of that allegedly horrible decade the 1980s. Composers in academia went on the attack against minimalism and Cagean influences, and I fought back, almost never so much against their music as against their intolerance. That my part in that fight is remembered today somewhat better than the original attacks is due to three reasons: Babbitt, Wuorinen, Davidovsky, et al attacked via scholarly journals and I was in a popular newspaper; much of their power was wielded behind the scenes via prize-giving organizations; and, since I am a better writer than they were, my words have achieved a longer shelf-life. Among the New Music America types Downtown, the situation unified a lot of us together for a glorious cause to which we were devoted. The collective feeling, the sense that we could make something exciting happen, energized and inspired us. If I had it all to do over again, I would change virtually nothing.

But the young, laid-back composers are horrified by all this. They find public argument distasteful; standing up for one’s aesthetic viewpoint an embarrassing faux pas; generalization about a style or repertoire impolite. As Edmundson goes on to say,

What my students are, at their best, is decent. They are potent believers in equality…

What they will generally not do, though, is indict the current system. They won’t talk, say, about how the exigencies of capitalism lead to a reserve army of the unemployed and nearly inevitable misery. That would be getting too loud, too brash. For the pervading view is the cool, consumer perspective, where passion and strong admiration are forbidden. (p. 9)

No one has ever called me cool. A certain perennial emotiveness has been noted, also the presence of passions and enthusiasms. A total insusceptibility to peer pressure was observed in my youth, and I have never blended in. I find the current system unfair, and I’m always on call to help blow it to bits. I’ve always been willing to stand up publicly for what I believe, and I’ve always considered the willingness to do so one of the signal virtues. But I can see now from this laid-back viewpoint what an embarrassing throwback I must seem, as Edmundson, in the book, suspects he is too, with his own passions and principled stands. One is no longer allowed to believe in his or her own aesthetic path so strongly as to extol it above others. Like Robert Frost’s liberals, we are too open-minded to take our own side in a quarrel. I have long known that my style of being a musician had become deeply unfashionable, but not until reading Edmundson did I grasp the process by which all of my most cherished virtues had become reinterpreted as social indelicacies.

I am not a particularly prolific composer, and have always been a little sensitive about it. The sensitivity started in college. In high school I spewed forth inept sonatas and chamber pieces by the ream with a frightening incapacity for self-criticism, and I swept into Oberlin with guns a-blazing. But my undergraduate composition teacher was intimidating and unsympathetic, and after a few months with him I found myself too petrified to compose anything. It took me many years to fully overcome the sense of insecurity that took root in me under his weekly lack of enthusiasm. It is common among a certain type of professor to say that, if a student can be dissuaded from becoming a composer, he should be; but if he can’t be dissuaded and you try for years anyway, the damage can be considerable and long-lasting.

At any rate, later there were other excuses for my relative lack of productivity. I’ve had to work like a dog to make a living all my life. The early years of being a high-profile critic took up a lot of psychic energy; it wasn’t like selling shoes while secretly working out musical plans in my head. And I got into the habit of writing books, which bring me more professional advantage than my music does these days, and writing them is so easy for me that I’m not likely to quit. I am selfish enough that I will deny the world the music I could be writing if I’m getting more jollies somewhere else.

But the real reason for the slow growth in my opus numbers, or probably more real than these other reasons anyway, is that I’m something of a conceptualist with a populist conscience. That is, to get inspired with a piece I need a concept, an idea, some friction of irreconcilables, that applies only to that piece. I do not have a habitual musical language that I can turn on and off like a spigot, or roll out by the yard, as so many composers do. So I get these inspirations like, hey, what if you had a rhythmic structure like this, but a harmonic rhythm that was totally independent of it, and you had to make it work and sound good anyway. Sounding good is the sticking point. I’ve had some compositional ideas I’ve carried around for decades, and I just can’t make them work, so I start a lot more pieces than I finish. And I am not like some of my fellow experimentalists I could name, who will find the concept sufficient and roar ahead with the work whether the listener can afterward tell what what the hell the piece was about or not. I conceive each work in some kind of arcane musical algebra, but if the initial results don’t sound wonderful and seductive, to me, I just won’t go through with it. Sometimes I try the same idea over every few years, and in several cases I’ve eventually figured out how to bring a recalcitrant concept to heel, usually by making my grandiose, austere premises simpler and/or more flexible.

Somehow I got, rather early, the idea that as long as I wrote over a hundred pieces in my career, I would consider that a respectable output. For some reason I did not want to be one of those composers known for their miniscule worklists of only 20 or 35 works: Webern, Varèse, Ruth Crawford, Ruggles, even Nancarrow (65, officially). For one thing, to make an impression with such a small catalogue requires not only a high consistency of quality but a trademark idiom, and I’m a little too variable in style and quality for that. And on the other hand, Beethoven only has 138 opus numbers, and though many of them are multiple works, anything over a hundred sounded vaguely in the ballpark. And some time in the past year, depending on what early works I feel like copping to in any current mood, I passed the one-hundred mark. With the two works I’m finishing up this week – a septet for the Ghost Ensemble called Sang Plato’s Ghost, and a chamber suite called Catskill Set – my official list has 105 titles. I made it!

And neither would I have wanted to be one of those composers who bombards the world with his or her fecundity. Darius Milhaud is one of my favorite composers, but a large percentage of his music sounds phoned in, and past the sixty or so fabulous pieces you quickly run into works that make you wonder why he bothered. Alan Hovhaness, similarly. I’m trying to figure out how much of Kaikhosru Sorabji’s music I really need to get familiar with. Composers like these need someone to write a book covering their complete output and letting all of us know what the gems are. It seems to me that extremely prolific composers create a perceptual barrier for themselves, because nobody after Schubert writes 500 masterpieces, and even a listening fan gets discouraged trying to profitably fill in the complete profile.

So “over a hundred” sounds good, and I can psychically relax a little. Breathes there the composer, today, who doesn’t occasionally stop and reflect that there’s already way too much good music in the world anyway, and that it seems either sadistic or masochistic to continue adding to it? I can keep composing when I’m really enjoying it, without the tad of psychic pressure in the back of my mind that I haven’t yet written enough. My worklist looks sufficiently respectable; a dozen or so of the works exceed a half-hour. And with having passed ten years as a blogger today as well, and finished the five chapters of my Ives book (out of fifteen, six of them already done) that I was determined to write before the semester started, I think that’s enough landmarks achieved for one summer.

REMINDER: Until the domain name transfers, my web site is currently here.

My web site is down at the moment. I was informed by Hostmonster, where I keep it, that my domain registration was going to expire. My domain was held by Melbourne IT. Melbourne IT informed me that they had sold it to Yahoo. Yahoo’s customer support is undoubtedly the absolute worst in the history of the internet. I keep circling through their website, and being told that I need to go to my “Business Control Panel,” and the link to that instead takes me back to the beginning and tries to sell me a domain name. I’ve tried everything. The other day I gave up after being on hold for 40 minutes. I did update my credit card info, and Hostmonster now tells me that my domain is good for another year, but I still can’t change the redirect for the same reasons given above. I don’t know how to negotiate this. Any advice welcome. In the meantime, if you have a Gann emergency and need to get to my website, there’s an alternate link here, thanks to Hostmonster, whose tech support is quick and efficient.

UPDATE, Aug. 27 – Transferred the domain name to Hostmonster, just waiting for Yahoo to release it, which could take a few days. Finally found a sympathetic text-support guy at Yahoo, too, ameliorating my above sentiment somewhat. Again, go here for the website in the meantime.

UPDATE, Sept. 2 – Web site is now functional again.

The International Society for Contemporary Music (ISCM) has asked me to give a talk on the state of American music at their November conference in Vienna – which strikes me as analogous to making Noam Chomsky the U.S. ambassador to the UN. I had to write a statement for their catalogue, which will be translated into German. Since it won’t appear in English, since the tenth anniversary has inspired me to think more about potential purposes for this blog, and since I have to expand it into a fuller paper, I thought I’d run it up the flagpole here and see who shoots at it. Also, the core of the argument relates to a book I’ve been asked to write and am mulling over, so feedback might help push me one way or another. Warning: the paper includes the words Uptown and Downtown, which is a blood-pressure hazard for some composers.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

The Uneasy, Unarticulated State of American Music

The term “American music†is devoid of specific connotative content today, even if we limit it to composed music in the concert tradition. If it means music made by Americans, Americans today come from all over the globe – and some whose ancestors were born here are working in global traditions. The American educational system pretty reliably exposes young composers to analysis of European modernist masterworks; jazz harmony; musical software; indigenous innovators such as Henry Cowell, John Cage, and Conlon Nancarrow; and a number of third-world musical traditions, most notably Indonesian gamelan, African drumming, Japanese gagaku, and Indian classical music. In addition, young composers absorb pop music and mass culture on their own. From this increasingly de-centered pedagogic tradition, they are understandably flung in all directions, flowing into a sea of aesthetic proclivities with myriad flavors but few demarcations or distinct categories.

This absolute openness in terms of aesthetic choices contrasts markedly, though, with drastic limitations on what kind of visibility or impact the composer can expect to achieve in American society. Major record labels continued to promote new music as a public service through the 1960s and ‘70s, but the corporate-friendly Reagan years made any such altruistic principles a thing of the past. Corporations now so heavily push kinds of music that can be easily categorized and that return a reliable profit that the amount of public distribution accorded new classical (or postclassical) music has decreased to a tiny trickle. It was reported during the 1980s that there were 40,000 self-identifying composers in the U.S. – by now the number must be considerably more than that. A few hundred of those, perhaps, can expect to become visible within a particular musical subculture. Those who manage to get a foothold in the orchestra circuit will receive marginally the most attention, for the capitalist reason that orchestras, which advertise heavily in newspapers, therefore get dependably reviewed by said newspapers. But even here, the bulk of the general audiences of those orchestras are more likely to consider the occasional living composer a necessary evil than a cultural leader.

It is arguable, I think, that there are no American composers today who have achieved the same public stature since 1980 as Philip Glass, Steve Reich, and John Adams did just prior to that date. While the obvious conclusion to be drawn from this would be that the generations of composers born after 1950 are rather lame, I suggest that another explanation is more compelling. The creativity of the best composers continues at a high level. But the skewed economics of distribution, combined with the sheer numbers of working composers and their smoothly-modulated rainbow of styles, makes it increasingly unlikely that any major figures commanding a wide consensus will emerge in the near future.

In 1967, musicologist Leonard Meyer published a fiery book that was widely read at the time: Music, the Arts, and Ideas. In it he predicted “the end of the Renaissance,†by which he meant that there would cease to be a musical mainstream, and that instead we would settle into an ahistorical period of stylistic stasis in which a panoply of styles would coexist. This seemed an outrageous forecast at the time, but Meyer’s prescience has been greatly confirmed.

The first stage of the breakup of the mainstream in American music was a separation in the 1960s and ‘70s into three large trends. The first was the stream of serialist music along an American adaptation of European 12-tone principles, which grew in political power and visibility during those decades. Almost at the same time, minimalism grew from the world of ideas John Cage had opened up, and offered a more timeless, less articulated aesthetic parallel to certain non-Western musics. Minimalism found a home in the lofts of Downtown Manhattan, and the music of the freer post-Cagean world came, by the late 1960s, to be called “Downtown music.†Serialist music grew to be mostly associated with academic music departments and ensembles, and after awhile – partly due to its association in Manhattan with Columbia University – earned the back-formation “Uptown music.†In the 1980s, some composers who rejected both minimalism and serialism, opting instead for a continuation of a more intuitively Romantic, conventionally orchestral modernist aesthetic, insisted on being called “Midtown†instead. Several of the most prominent “Midtowners,†such as George Rochberg, David Del Tredici, John Corigliano, and William Bolcom, actually returned to employing the conventions of late Romanticism (Mahler’s idiom being especially popular) with an accompanying dose of irony, satire, or collage. In 1983 the term “New Romantic†was coined for this development.

These divisions played havoc with the paradigmatic modernist duality of conservative versus avant-garde. Most obviously, the prior association of tonality with conservatism and atonality with avant-garde fell apart. The Uptown serialists could claim to be avant-garde for posing the most challenges to the audience’s perception. The Downtown minimalists could claim avant-gardeness by having transcended European genres and embracing a world aesthetic. And the Midtown New Romantics could claim avant-gardeness for having jettisoned even the modernist assumption of stylistic homogeneity. A composer writing a highly tonal piece might be taking Benjamin Britten (conservative) as a model, or Arvo Pärt (avant-garde); and who cold tell for sure?

The battles among these three segments of the composing community, each trying to take on the mantle (and attendant funding and distribution) of the new mainstream, were fierce, played out in newspaper diatribes, college classrooms, and lecture halls. After a few years, though, this state of things began to dissolve. First of all, the number of 12-tone pieces (or at least the number of composers publicly extolling 12-tone principles) fell off dramatically in the late 1980s. Minimalism, entering the orchestra world through commissions given to Glass and Adams in particular, became somewhat watered down from its original hard-core principles, and morphed into a textural lingua franca. The extremes declined, as did the prestige of being on the extreme. The shape of American music went from looking like three separate streams to more like a bell curve. There are still adherents of the “New Complexity†in the U.S., Jay Alan Yim possibly the best known. At the other end of the curve, there are those attached to the Wandelweiser school of silence and extreme duration and simplicity, like Michael Pisaro. But that the guru of New Complexity is a British composer, Brian Ferneyhough, and the Wandelweiser a European group, may further suggest how un-American it is to be an extremist these days.

It is against the background of those battles that many of the composers born after 1975 have defined themselves. The new generation of composers is conflict-averse, its discourse reduced to a broadly tolerant pragmatism. However much the young composers believe they have blessedly transcended ideology and partisanship, though, they have nevertheless inherited some of the previous attitudes in a less articulated form. Instead of distinct categories, what we have is a continuum of opinions along the accessibility/difficulty scale: how much should the composer keep the audience in mind? What should be the relation, if any, to pop music? Is the educated elite of academia a sufficient audience? Should the composer ignore all questions of perceptibility and follow his pleasure? Is there, indeed, any way to predict what music will go over well with an audience and what won’t? Does the long tail phenomenon of internet distribution render all such questions moot? What is most typical of American music at the moment, I would argue, is a large-scale, implicit, almost publicly unarticulated debate on the social use of music, of what it is made for.

For obvious reasons, the composers who actively court public relevance have been the most visible. Starting in 1987, the Bang on a Can festival, run by Michael Gordon, David Lang, and Julia Wolfe, has championed music of a hard-hitting, exciting profile. The baseball-cap-wearing founders have distanced themselves from the perceived elitism of classical music presentation, presenting in unusual and informal spaces and replacing the formality of program notes with personal appearances by each composer performed. A certain amount of rock-star wanna-beism is in evidence. The much quieter Common Sense collective, a bicoastal group of eight composers including Dan Becker, Carolyn Yarnell, Belinda Reynolds, and others, has banded together to seek group commissions from ensemble to ensemble, like a roving herd of compositional locusts. With these new paradigms begin the strategies of most composers who have become visible since. 1. Eschew elitism and traditional formality in presentation, regardless of what the music is like. 2. Control your own distribution and the means to create your own performances. In either case, take your music into your own hands and be independent of existing institutions.

The Bang on a Can people eventually formed their own label, Canteloupe. Probably the most visible group of younger composers in recent years is that united by another such startup, the New Amsterdam label, including Judd Greenstein, Nico Muhly, William Brittelle, Corey Dargel, and others. Brittelle’s theater music tackles the conventions of television. Dargle’s works are elaborately composed pop songs on texts of sometimes shocking personal honesty. Anti-Social Music, despite its ironic name, is a group (including Pat Muchmore, Andrea La Rose, and others) that has specialized in extreme informality of presentation, often setting off the music with abundant humor and surreality. ThingNY, run by Paul Pinto, is an ensemble that has tried publicity stunts such as commissioning brief works via mass e-mailings. The resulting styles of all this music are not always predictable from the format, the emphasis being on finding a new presentation paradigm free from associations of either conventional classical music performance or the stylistic subcultures of the 1980s.

That these groups have garnered the most publicity does not mean their approach is numerically dominant. A probably larger number of composers still move through more traditional channels, attending the most prestigious possible grad school, studying with influential teachers, applying for prizes and awards, and angling for orchestral commissions. Even here, a correlation with style and idiom cannot be assumed. One of the most successful young composers on the orchestra circuit, Mason Bates, moonlights as a club DJ. His orchestral works such as Omnivorous Furniture (2004) typically include him playing a noisy music of pop beats from his laptop in the center of the orchestra. Even so, there is an intermittent streak of lyric romanticism in his music, possibly drawn from his studies with one of the seminal New Romantics, John Corigliano. Some mention should also be made of how widespread the influence of John Adams has become on young musicians’ orchestral music. His propulsive repeating brass chords, dotted by abundant and explosive percussion, have become a rather well-defined style of their own. And since so many commissions for living composers are in the form of ten-minute concert openers, this style/format combination has acquired the jocular nickname “subscriber modernism.â€

Microtonality is a steadily growing field, more so on the West Coast. Composers working in equal-step scales are far more numerous, and their music tends toward esoteric complexity; those fewer working in just intonation, with Ben Johnston and La Monte Young as models, often opt for meditativeness. Boston has its own microtonal subculture based on a 72-pitch-to-the-octave scale, based on the practice of Ezra Sims and the late Joe Maneri. This overall trend remains impeded by technological hurdles and performance difficulties. John Adams, though, made an unusually public microtonal statement with his 2003 orchestra work The Dharma at Big Sur, which incorporated natural harmonics in the brass.

Moving outward from these recent, more definable trends, it is fairly impossible to generalize further about what’s going on in American music. American composers write for Javanese gamelan with or without orchestral instruments and electric guitars (Evan Ziporyn has been active in this area); perform music from their laptops; write symphonies; create sophisticated MIDI versions of orchestral music; subvert pop-music conventions (a specialty of Mikel Rouse); base their music in Balkan singing styles. While many composers make an ambitious bid for social relevance, many, many others are content to accept their marginalization in American culture in return for total autonomy. One thing we all grow slowly more aware of is our increasing disadvantage, as individual low-subsidy artists, in terms of technological sound production compared to the massive resources of corporate film and popular music. Wealth brings a sonic sophistication that the autonomous sound-experimenter can only envy.

One can only report that musical creativity continues at a high level in the United States, pursued under a troubling and sometimes debilitating set of circumstances. At one end is the corporate world of commercial music with its untold riches and aesthetic co-optation; at the other end, the rarified air of the unpublic career totally subsidized by academia. In between are thousands of composers trying to strategize an artistically fulfilling career in a capitalist society run amok, poisoned by money and ruled for the benefit of the richest 0.1 percent. In short, we are all, every one of us, trying to discern what kind of music it might be satisfying, meaningful, and/or socially useful to make in a corporate-controlled oligarchy. The answers are myriad, the pros and cons of each still unproven. We maintain our idealism and do the best we can.

The new-music blogosphere seems to have exploded into existence in the summer of 2003, judging from the number of such blogs celebrating their tenth anniversaries lately. Although I wrote a couple of entries beforehand, I saved the official unveiling of my blog for August 29, 2003 – without even reflecting, as I recall, that it was the 51st anniversary of the premiere of 4’33” (and of course not knowing that it would become the anniversary of Hurricane Katrina). I also, inexplicably, failed to check the prevailing astrological transits, whose oppositions of Mars and Uranus to practically everything else guaranteed, in advance, plenty of heated argument. Anyway, PostClassic’s own tenth anniversary is upon me, and I suppose it would be churlish of me not to complete the cultural moment with an accounting of my own activity.

Scattered among the celebrations are some laments, apparently initiated by the always sympathetic Elaine Fine, that new-music blogs are attracting fewer and fewer readers, or in other cases going inactive (though others have applied more technological sophistication than I possess to disputing these impressions). I imagine that I am one of the blogs considered as having arrived at the inactive category, down from as many as 27 posts in a month to as few as two quite often lately, and those mostly announcements. I’m sure that my readership is a small fraction of what it used to be, and I am quite happy about that. Weary of finding my most bedrock perceptions deemed controversial, I am content to preach to the choir that remains (Hi David!, Paul, Lois, Doug, Lyle, Brian, John…). It is tasteless, I realize, to repeat compliments one has received privately, but I was told this weekend I had become the Bad Boy of music just by thinking too deeply about matters that everyone else takes for granted. I’m sure others would formulate it differently. As I’ve said before, I write my music for the multitudes, but I would prefer PostClassic be a haven for that tiny minority of musicians who share my views on new music – such as, that it should be written for the multitudes. If my audience further dwindles to the point that this becomes an unnoticed site for my private musings nicely typeset and illustrated, that will be sufficient. In my 20s I kept a journal, and I enjoy the hobby.

The truth is, I’m in rehab. My decades-long lifestyle as a music critic had made me an attention addict, and I consciously decided to recover. Unable to get a composing career quickly off the ground in the years following grad school, I made it my strategy to flash my name into the public eye every week. In the ’90s I was publishing more than a hundred articles a year (with considerable economic incentive, mind you, since I had no other living). The Village Voice began shaving down my column starting around 1999; PostClassic gave me a panoramic word-count again, and, miraculously releasing me from the necessity of news pegs, left my subject matter wide open as well. You may have noticed that I’m a compulsive writer. I believe I’ve published more than four million words. A year ago a magazine editor called me, begging for a 1500-word article to fill an unexpected gap; I wrote it in 75 minutes and sent it to her. I’m not the best, but I’m sure as hell the fastest. Spewing words out into the world every week had become a habit. At some point I realized I was being buoyed along by my own momentum, and getting less and less of what I wanted from it in return. My son worried about his black metal band Liturgy getting “overexposed,” and I started to feel somewhat overexposed myself.

On the morning of July 1, 2011, for whatever internal reason, I woke up and abruptly realized that I was tired of the effort, and most of my other efforts as well. I had been living as a martyr for certain benign forces in new music (Downtown, experimental, accessible), and I didn’t want to be a martyr anymore. I wanted to self-indulge, satisfy my own aims more directly, and let the culture-at-large go to hell if it was so adamantly determined to. I had already been complaining for a year. I was, and remain, particularly weary of the composing world. We raise young composers with grand expectations that will almost certainly remain unfulfilled, and the chief proficiency they emerge with is a vast verbal and conceptual framework for invalidating the music of others. There has to be something about the way composers are trained that makes us all so competitive, rigid, and ungenerous; an education that prepares anyone for that kind of life is a mockery. This past weekend some colleagues from another school and I marveled at how many kids keep coming to college to be composers, and wondered what in hell they think they will ever get from doing so. On that day in 2011 I changed course, though it’s still not fully clear what my new direction is yet. That month I wrote only one blog entry, a brief paragraph. I needed to relearn what not being heard from frequently felt like.

This past weekend I also had a visit with Russian musicologist Olga Manulkina, who has written a thick history of American music, in Russian. She wanted some advice about teaching American music, she said, because the composers at her school harshly disparage John Cage and minimalism, and tell her she shouldn’t be teaching them. She looked astonished when I chuckled and replied, “Just like in America.” She wants to bring me to St. Petersburg to lecture for a new music criticism and arts management program she’s involved in, and she asked me what kind of vision I would present to the students. Pressed, I fell back almost by rote on my old catechism: “I believe that music can be intelligent, innovative, and original, and still be attractive and accessible to large audiences.” That was the philosophy behind the New Music America festivals (1979-1990), which ran from when I was in grad school to my peak years at the Voice, and of which I rather consider myself a product, having been involved with the second and fourth and having reviewed the later ones. I think it’s also the philosophy of the Brooklyn Academy of Music, which I consider the country’s most honorable large arts presenter. So like most of us I’m a creature of the time and place of my youth: a relic of the late-’70s new-music boom, and withal something of a dinosaur.

“Music can be intelligent, innovative, and original, and still be attractive and accessible to large audiences.” That’s the vision I would keep rooting for in PostClassic, but I’ve said it in these pages every way I can think of, and they’re all available in the archives. The idea seems to achieve less and less traction. There is no longer any visible sector of the music scene that embodies it, and so all my explanations start over from scratch. Every restatement brings arguments I’ve defended myself from a hundred times. No progress is made. Every year hundreds of new composition graduates descend on the world having dutifully absorbed from their teachers that audiences can’t be thought about, and that musical obscurity is a sign of integrity. Meanwhile I’ve discovered the cool contentment of writing about long-dead composers, and am getting interested enough in 19th-century religious disputes as part of my Ives research that I wonder if my next big phase shouldn’t take me outside of music altogether. Unlike music, scholarship can become more fun the more esoteric it gets.

In short, the relative quiescence of PostClassic should not be taken as constituting evidence that the music-blogosphere is dying, or that fewer people are reading music blogs, or any other collective trend. Any synchronicity between me and them is purely coincidental. It’s just a certain point in my life.

During the Civil War, Joseph Twichell, future father-in-law of Charles Ives, worked as a Congregational chaplain in the Union Army next to a Jesuit priest named Joseph O’Hagan, with whom he became lifelong close friends. After the 1862 Battle of Fredericksburg, the two exhausted themselves helping the wounded, and then slept huddled together beneath blankets against the December cold. O’Hagan laughed, and, when Twichell asked him what was funny, replied, “The scene of you and me – me, a Jesuit priest, and you, a Puritan minister of the worst kind, spooned together under the same blankets.†Twichell loved telling this story at renunions. I found it on page 97 of Steve Courtney’s excellent Joseph Hopkins Twichell: The Life and Times of Mark Twain’s Closest Friend, which is an eminently enjoyable history of a lot of pre-Ives background, though eccentric son-in-law Ives is only mentioned in a few spots.

So this clearly explains the oddly uncontextualized comment Ives drops in on page 85 of his Essays, where he says that Beethoven, upon having his orchestration updated by Mahler, was probably “in the same amiable state of mind that the Jesuit priest said God was when He looked down on the camp ground and saw the priest sleeping with a Congregational chaplain.†What a weird little personal thing to include (and potentially confusing given today’s euphemistic use of the phrase). I’m finding a lot of little explanatory factoids about the Essays and am having trouble placing them in the narrative; maybe easier to put them here.

My good pianist friend Lois Svard, with whom I used to teach at Bucknell and for whom I wrote my Desert Sonata, got interested in her last years at Bucknell in neurological aspects of creativity and taught classes in it every year. She’s done creativity workshops for corporations, too. And now she’s started a blog on the subject called The Musician’s Brain. I look forward to it.

The past two days have been among the most remarkable I’ve had in years. John Luther Adams and his wife Cindy came up from the city to visit, composers Robert Carl and Ken Steen came from Hartford to attend some of the Bard festival, and we all spent part of yesterday attending the performances of Robert Ashley’s Perfect Lives by the New York group Varispeed, which took place in various spots west of Woodstock. Here are Robert, Ken, Cindy, and John (wearing my new hat) on my deck:

(You can click on these photos and they’ll open in better focus.) The Perfect Lives performances, which I missed when Varispeed did them in New York two years ago, were quite remarkable, uncannily true to the spirit of Ashley’s work though somewhat altered in format. A new movement was performed every two hours, each one in a different space corresponding to the setting of that scene in the opera. We arrived in time for the “Supermarket” episode, which took place in the IGA store in Boiceville (Ashley can be seen in a light blue shirt sitting in the back on the right):

For each scene a different performer played the Ashley/narrator role, and at the IGA Paul Pinto (seen here a little in the back left with a microphone) did a stunning job of channeling Ashley through the store’s PA system:

With instrumentalists in pursuit they threaded up and down the isles of the supermarket, followed by a staunch Ashley crowd of about 75 who were there all day, plus dozens of shoppers who were just trying to buy groceries; one man, John told me, got disgusted and stormed out without his purchases, and I replied, “Just like a regular concert.” Ashley, meanwhile, looking pleased as punch, stood around using a grocery cart as a walker; here he’s joined by John and my wife Nancy:

The fun of having an opera meander through a grocery store, around real customers, was too fun to be believed. Ken asked me “Is this the future of opera?” I said, “I think you’re being optimistic.”

Before heading to Phoenecia for the “Church” scene, we made a slight detour to see the Maverick Concert Hall, where 4’33” was premiered, and which the others had never seen before. Though the hall was closed, they assembled in the outdoor seating as though they thought they could get a lecture out of me about it:

Singer Aliza Simons did a beautiful job in Ashley’s role presiding over the opera’s wedding scene at Phoenicia United Methodist Church, her voice at the end starting to sing more in the inflection style of Ashley regular Jacqueline Humbert:

“The Backyard” (the scenes were played out of order for logistical reasons that will be obvious if you think about it) took place in the vegetable garden of Mount Tremper Arts, the organization that bravely sponsored the marathon. As Ray Spiegel did a ripping job on tablas, Gelsey Bell sang the role of Isolde, standing in the doorway to her mother’s house, and Aliza Simons walked around the perimeter barefoot playing the occasional accordion riff:

Ashley (here with his wife Mimi Johnson standing behind him, John Luther Adams in the background) was transfixed:

It was an incredibly moving, incredibly poetic event. Unfortunately we had to get John and Cindy to a train station, and missed the last two scenes, but a Pittsburgh performance is planned that I may try to make it to. Varispeed did a phenomenal job of taking Perfect Lives apart, putting it back together their own way, and keeping the spirit completely intact.

The previous evening we had all eaten at Mexican Radio in Hudson:

Ken, Robert, John, and I are, I suppose, as simpatico a group of four composers you could find anywhere. All being ardent Ivesians, we were discussing my Ives book, and John reminded us all why he’s John Luther Adams by asking a pointed question that I, with my habitual verbosity, would have never ventured, but which elicited his usual profound results. He challenged each one of us to come up with the one word that summed up Ives’s significance for us. Ken said “Freedom.” Robert said “Miscegenation” – and then explained that what he meant by it was “reconciling irreconcilables.” John, for himself, said “Space.” And I said “Oversoul” – maybe because I’m reading too much Emerson lately, but also because a close reading of the Essays has convinced me that what Ives most valued was the suprapersonal expression that came from beyond the artist’s individual ego, which has always been a concern of mine as well. I’m sure each of us said something deep about our own music in the process.

And then, because all four composers had brought bottles of expensive scotch, we went home to continue the discussion.