Just became aware that Sarah Cahill’s recording of my piece War Is Just a Racket is up at YouTube with John Sanborn’s video for it, which I hadn’t seen since the premiere in 2009.

Archives for January 2016

Needle Found in Haystack

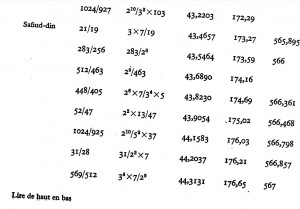

A correspondent named Tim Scott has found a typo in the Tableau Comparatif des Intervalles Musicaux, Alain Danielou’s encyclopedic 1958 catalogue of all even marginally significant intervals within an octave. On the right-hand bottom corner of page 48, the interval listed as 569/512 should actually be 567/512, as 3 to the 4th power times 7 is, of course, 567:

And as Tim points out, this is one of the intervals used in The Well-Tuned Piano. All fanatical microtonalists please mark your copies accordingly. That is all.

UPDATE: The day that Amazon extended its reach into the nation’s used-bookstores was one of the greatest days of my life, and has compensated for many of the indignities of living in the 21st century. I first saw Danielou’s Tableau Comparatif des Intervalles Musicaux in La Monte Young’s apartment, and lusted after it mightily. More than a decade later, once the used-bookstores went online, I found it over the web in a little store in Oregon. The nice lady who sent it to me had no earthly idea what it was, but said, “I knew someone was eventually going to know what that was and want it.”

FURTHER UPDATE 2.5.16: In response to this post, over at Disquiet, the ambient/electronica site,

Marc Weidenbaum has posted a series of pieces exploiting the difference between the 567th and 569th harmonics. It seems his internet group, The Disquiet Junto, posts a compositional challenge each week, and everyone has four days to come up with a short piece in response. This is really cool!

How Cage Makes Us Philosophize

One name that musicians may run across often in the literature on John Cage and not recognize is Richard Fleming. He’s a philosophy professor at Bucknell University, a friend of mine for twenty-five years, and he edited, among others, two books with our mutual friend Bill Duckworth, John Cage at Seventy-Five and Sound and Light: La Monte Young and Marian Zazeela. Richard spent a lot of time with Cage, and teaches a fascinating-sounding course, in the philosophy department, comparing the respective Harvard Lectures of Cage and Leonard Bernstein – almost unimaginable, since Bernstein’s lectures are about the underlying grammar of music and Cage’s are chance-determined words and phonemes. A lot of the material, heavily involving Wittgenstein as well, ended up in his beautiful little treatise Evil and Silence.

Anyway, due to problems with publishers similar to ones I’ve encountered in recent years, Richard has decided to publish his long article on Cage via the internet, and here it is:

Listening to Cage: Nonintentional philosophy and music.

I’ve been saying for years (as you all know) that Cage wasn’t a philosopher, by which I have meant that Cage’s writings don’t fit the genre of philosophy as I know it. But Richard tackles the issue head on, and insists that Cage was a philosopher in a very different sense, in that his music makes us rethink our concepts of the world. “Listening to Cage,” he writes,

awakens and stirs us to resist, accept, embrace, reflect, frown, laugh, question, affirm, challenge, walk away, dance, and talk. It brings to mind the brackets or conditions of possibility, the agreements, which govern what we do. This is nonintentional philosophy and music.

He quotes Wittgenstein frequently: “[P]hilosophical problems arise when ‘I don’t know my way about’; and then new questions come to mind,” and this is the state of mind Cage’s music induces. And he closes with a meditation on the tape piece Fontana Mix:

Having provided a grammatical place for our talk and listening, we end this brief excursion in nonintentional philosophy and music by answering more directly our original question about Fontana Mix: Why would we listen to this? It is not hard, now, to suggest that listening to Fontana Mix awakens us from the tired standards and routines in which we find ourselves. It agitates and reorients our sense of importance. It tests our sense of mistake, interruption, ruin, and justification. It clears the ground for questioning our concepts anew.

It’s a deeply-considered article and very elegantly written, and ever since I read an earlier version of it several months ago I’ve been soft-pedaling the Cage-not-being-a-philosopher notion. I am convincible, and Richard’s too brilliant to argue with.

Except That

I’m putting up a new version of my microtonal work Solitaire:

It’s been sound-produced by M.C. Maguire, whom I consider the best Canadian composer of my generation, and in fact the most original figure in Canadian music since R. Murray Schafer (and I do follow Canadian music). My electronic/microtonal works are scored and notated, but I don’t have the electronic chops to realize them in a sophisticated way, and Mike is my software creative genius go-to guy for putting them together. He takes my template recording and retains the timbres I composed, but enriches them and blends them better and adds effects that make the overall sound texture more dynamic. I think he’s done a fabulous job here. In short, I compose the pieces in every detail, and he performs them. The situation makes perfect sense to me, but it renders my music neither-fish-nor-fowl where the electronic composers are concerned. I don’t care. Coloring within the lines never appealed to me. I got sick of writing new chord progressions no one had ever heard before and having people react, “Ew, I can’t stand those timbres!” and dismiss the music. I’m making a push to get my microtonal works out on CD.

I recently mentioned that my Orbital Resonance was the kind of piece composers would be impressed by, and I suspect Solitaire is the kind of piece of mine that makes them shake their heads over me. I have always supported the position that, for many people, words can help people understand music better (otherwise I have wasted much of my life), and so at the risk of raising arguments where none were intended, I’m going to mount a defense of Solitaire against imagined objections.

Like much of my music, the piece doesn’t wear its strangeness on the surface. On the surface are the normal elements of music: melody, harmony, meter, even a slight retro pop sensibility. It seems naïve (or did before Mike got ahold of it, anyway). Its surface naivete is a carefully calculated construction. It is almost cartoon-like, and I’ve always admired cartoons (in fact, at age twelve before I became a composer I wanted to be a cartoonist) for their clean, hard lines, their indifference to realism, their personality-expressing, deliberately pixelated approximation of reality. The strange part – the microtonal connection of chords via intervals based on the 11th and 13th harmonics – is backgrounded, and is so modestly finessed that a casual listener might not even notice it. In fact, I laced this microtonal piece with normal iv-V-vi chords in the key of Eb, so there are passages in which the ear is lulled into thinking there is nothing unusual at all. In its notes, it’s a piece that could have been written seventy years ago – if the preceding two centuries had been very different.

I have sometimes thought of myself as the anti-John Zorn. He tried to make everything as fast and discontinuous and disconcerting as possible, and I sometimes try to make everything sound as normal as possible – EXCEPT THAT…. And that except that is the piece. It’s my philosophical link with my favorite living composer Mikel Rouse, whose music also sometimes sounds so normal that people miss the weird ironies in the background. I’ve been reading Philip K. Dick recently, and of course always knew him by reputation, and there may be a Dick-ish quality to it: a suburban house, kid playing in the backyard, everything is normal except that it’s an alternate reality and these are androids who live their lives backward, or something else from an alternate universe.

Also Solitaire‘s form is, I think, one of my finest achievements. It’s written postminimalistically in rhythmic modules, and the challenge I set myself was to create, via the melody, a subjective and spontaneous sense of form within a simple framework that provided only a method, not a structure. At one point the melody goes into steady quarter-notes for awhile (my old friend Doug Skinner’s favorite rhythm), later it falls into a kind of ecstatic dance in 5/4, then plays note-fragments meditatively, and ends by repeating a three-note motive every six beats, even though the meter and harmony are changing irregularly underneath it – an effect I don’t think I’ve ever heard in any other music. Overall, I wanted the piece (inspired by a Robert Ashley comment and dedicated to him) to sound so normal that people uninterested in new composition would find it appealing and easy to follow, while new-music experts would hear chord progressions and microtonal voice-leadings they’d never heard before. It’s the opposite of what I think of new music as a genre generally represents: crazy stuff that doesn’t even strike the uninitiated as music, but whose elements are quickly recognized and understood by aficionados. As someone who has spent his life defining and classifying new music, it is understandable that as a composer I sometimes have an impulse to get far away from it, with the result that it seems to other composers that I’m not even trying to be original, when in reality my irony has brought me around 360 degrees.

I don’t think Solitaire is my best piece, because it is far from being the most ambitious, but among my microtonal works of several years ago I do think it achieved an optimal point of crystallization for the ideas I had at the time. As with everything else you may listen to it and not like it and that can’t be helped. But now you are at least assured that I composed out of some sense of artistic necessity, and that the piece’s refusal to cooperate with the modernist project is deliberate.

“You can’t do what you want, but anything goesâ€

Wow – speaking of Julius Eastman and Morton Feldman, the SUNY Buffalo Music Library has made available the tape and a transcript of the speech John Cage made at June in Buffalo in 1975, when he was angry with Julius for having undressed a young man during a performance of Cage’s Songbooks the previous evening. I was in the room, a 19-year-old Oberlin student between my sophomore and junior years of college. Some of the details I now realize I had misremembered. I have recounted elsewhere (“No Escape from Heaven: John Cage as Father Figure,” in The Cambridge Companion to John Cage, 2002) the story of how there were too many students for Cage to look at everyone’s work, so he assigned us random numbers and used the I Ching to decide who would get to present something. One young woman protested vehemently against this randomness – Cage refers to her here as Sue, I had transposed her name to Mary – and on Thursday of the week, as he says here, he dropped the system and let anyone who wanted to, speak. George Cisneros, a composer from Austin who asks a couple of questions, was a Texas friend of mine (he had hitchhiked to get there). Peter Gena was there; I didn’t meet him, and he had missed the performance, but I would study composition with him two years later at Northwestern. It was my only time to see the great musicologist Peter Yates. Other student composers from Oberlin, Sam Magrill and Michael Manion, were present with me.

Some SUNY grads may remember that there was, at the time, a fabulous record store across the street from the university, called Record Runner, the best record store I’d ever seen. Incredible avant-garde import section – those words meant something back then. My parents had sent me with $200 spending money and I spent almost all of it on records (which cost only $4 to $6 at the time), getting my food expenses down to about $1.50 a day by having only one meal, a shrimp basket and a Coke. I first read Cardew’s Stockhausen Serves Imperialism in the SUNY library there. What a kick in the head!

Other memories, while I’ve got them stirred up: The students had arrived the evening before the conference started, and so on Monday morning we were all enthusiastically talking to people we’d just met. Feldman came into the hall and went to the podium and grandly announced, “I’m Morton Feldman.” Almost no one stopped talking, we were enjoying ourselves so much, and he looked a little crestfallen. More than one person, independently, drew caricatures of Feldman as a frog. At one lecture Cage brought in (as he often did, apparently) some edible wild plants he had found on campus, and passed them around so we could see what to look for; a friend of mine, misunderstanding the purpose, said, “Oh thank you,” and ate them. I had a talk with Christian Wolff about Buckminster Fuller, whom, to my disappointment, he seemed to think was brilliant but politically naive. Feldman took several of us for a couple of group lessons; his eyesight was so bad that he looked at people’s manuscripts from three inches away, and his cigarettes (which he went through so fast that he would sometimes absent-mindedly light one when another was only half-smoked) left many a burn mark on the page. Nearly all of his suggestions were about timbre, suggesting more exotic instruments than the ones we’d used. One student told a story about having had a lesson with Toru Takemitsu in which the latter said nothing for an hour, then closed all the scores and said only, “Pay more attention to tone color.” Feldman loved it.

We were all discussing articles from the serialist magazine Die Reihe back then, and when we had a disagreement about Stockhausen, several of us stayed up half the night trying to connect with a German operator who spoke English to get Stockhausen’s phone number. Luckily for him, we failed. During the Friday session I showed Cage my piece Satie, a chamber piece with texts by Satie that I now consider my opus one, all in the C-major scale; Cage kindly said “It makes me want to hear it.” Other stories I’ve told elsewhere. I was such a neurotic, sheltered, immature kid from Texas that I blush to remember it. It was a formative three weeks for me, obviously: Cage, Feldman, Brown, and Wolff, all of whom I would see many times again over the years, but never again in such a concentrated dose. The amount of scholarship that’s been focused on that event blows my mind, and to hear a recording of what I heard at the time makes forty intervening years vanish like an immaterial mist.

Thought for Feldman’s Birthday

As late as 1986, the year before his death, he confessed, “I have no complaints about my career, but I always wondered why it really doesn’t take hold.†(H/T David Beardsley)

As late as 1986, the year before his death, he confessed, “I have no complaints about my career, but I always wondered why it really doesn’t take hold.†(H/T David Beardsley)

It was later, in April of 1987, by the way, that I wrote in the Village Voice that “some people consider [Feldman] the world’s greatest living composer.” He read it, and died in August.

Word.

Making the World Safe for Julius

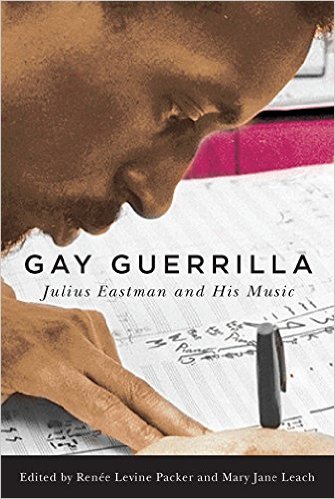

I have just received my own copy of the new book about Julius Eastman: Gay Guerrilla, edited by Renée Levine Packer and Mary Jane Leach. I’m afraid my own contribution to it is a little perfunctory, probably containing nothing that you haven’t already read in my blog or in the liner notes to the New World CD. I had attempted to do some musical analysis and then found I was crowding someone else’s territory, and so retreated into my moment of fame as the author of Julius’s obituary. But Renée’s biographical chapter, which she gave a presentation on in October, is quite extraordinary. Most importantly, who would have believed, in 1990, that in twenty-five years there would be a book out about our brilliant friend who had disappeared so mysteriously?

I have just received my own copy of the new book about Julius Eastman: Gay Guerrilla, edited by Renée Levine Packer and Mary Jane Leach. I’m afraid my own contribution to it is a little perfunctory, probably containing nothing that you haven’t already read in my blog or in the liner notes to the New World CD. I had attempted to do some musical analysis and then found I was crowding someone else’s territory, and so retreated into my moment of fame as the author of Julius’s obituary. But Renée’s biographical chapter, which she gave a presentation on in October, is quite extraordinary. Most importantly, who would have believed, in 1990, that in twenty-five years there would be a book out about our brilliant friend who had disappeared so mysteriously?

I had mentioned that in October I attended a symposium about Julius in Philadelphia, but the ensuing weeks were too busy for me to write about it. Dustin Hurt, director of the organization Bowerbird, wants to present a festival of Julius’s music, as he has presented festivals devoted to Cage and Feldman in the past. But Julius is not someone you spring on an unsuspecting public unprepared: how do you warn a wide audience that you’re performing pieces with titles like Crazy Nigger, Evil Nigger, and Dirty Nigger, and that they are not what you might think at first? And so Dustin had the remarkable idea of bringing three of Julius’s friends – me, Mary Jane, and Renée – plus Eastman scholar Ryan Dohoney, together with about a dozen African-American artists and scholars from the Philadelphia area, to see, in short, how we should go about marketing a Julius festival without raising alarms and stoking resistance. The two days full of frank discussion we shared were sharply enlightening. All the artists and scholars, almost none of whom had heard of Julius before, were enthusiastic and on board, but understandably wary about presentation. As one young woman said, “This is the first time I’ve ever sat in a room with white people casually using the word ‘nigger’ before, and it’s kind of creeping me out.” (So I switched to calling the pieces CN and EN.) We even had two BDSM experts ready to discuss, in detail, Julius’s role-playing activities in that underworld – which was starting to creep me out.

The upshot seems to be that the festival will go forward in a year or two, with plenty of mediation by community leaders in the area. It struck me, by the end, that Julius Eastman was a little parallel to Erik Satie, someone that the classical music world was never going to figure out how to deal with. And then I started thinking about all the other composers the classical music world doesn’t know how to deal with, and realized that one doesn’t have to be very much of a deviant to get the classical music world all befuddled.

Cribbing from Frankie

I have never been one to post lists of what I’m listening to lately, for quite a number of reasons. One is that it would often be embarrassing. Right now I’m driving around listening to old Frank Sinatra records from the fifties. I feel like my music needs occasional infusions of vernacular music, specifically music that was tremendously popular at some point, music that people paid for because it was attractive and entertaining. I can supply the complicated cross-rhythms and microtonal voice-leading myself, but I need some DNA from the mainstream: a jaunty rhythm, even just a tempo, a surprising harmonic twist, a melodic quirk. A few minutes ago one of Nelson Riddle’s arrangements ended with a big brass cadence, and then immediately repeated the cadence in the strings, so quietly that it sounded like an echo, and I shouted, “Yes! I’m gonna do that!” What a temptingly style-independent gesture.

In the early 1990s a meme made the rounds downtown that new music, in order to be authentic, must be based in the vernacular. I remonstrated, pointing out that there’s plenty of great music with no vernacular connections: Feldman, Varèse, Tenney, Xenakis. The only reason to ever say music must do something is so that the next day some genius will write a great piece that doesn’t do that. (“Must follows music only in the dictionary,” I wrote in the Voice.) But I am so lacking in the common touch myself, raised in such a rarefied atmosphere, so deficient in street smarts and folksy charm, that I have to steal it from somewhere, and so little sound-shapes from Swing Era jazz, Waylon Jennings, Edith Piaf, Jimmy Buffett, even Strauss waltzes show up here and there in my music, probably unnoticed by anyone but me. I’m sure I have some bizarre blind spots in my appreciation of the world’s musics, but I’m no snob.

Boulez est mort

I have little to say, but I couldn’t pass up the chance to use a headline I’ve been holding in reserve for three decades. When I interviewed Pierre Boulez in Chicago in 1987, we touched on his notorious 1952 article “Schoenberg est mort,” and I asked him if someone would someday need to write an article “Boulez est mort.” He laughed, and said, “Maybe I should write it myself.” And then he lived another 28 years. A lot of his music that we studied closely back in the day I find forgettable, but, oddly, I was just thinking yesterday how much I love Pli selon pli, and that I should listen to it again. Rituel was a very influential work on me. And Repons I enjoyed hearing live, and had a blast reviewing the Chicago premiere.

The greater significance for me is that an entire generation is now dead, a generation around which I formed part of my musical personality in high school. Boulez, Stockhausen, Maderna, Pousseur, Ferrari, Ligeti, Barraqué, Kagel, Zimmermann, Berio, Nono, Bussotti, Xenakis – I loved them, I explored them, I was inspired and mystified by them, I carried their vinyl Deutsche Grammophon and Wergo records to college with me; because I had already been seduced by Copland, Harris, Schuman, and Bernstein on one hand and Ives, Cage, and Feldman on the other, I could not totally succumb to them; because they spoke in dictatorial terms I developed a genial oedipal hatred for them. As happens, now that they are all gone only the affectionate feelings remain. In grad school I analyzed every note of Boulez’s Second Piano Sonata, which I had never heard – and I knew it so well that when I finally listened to the recording, I cried. Today I wouldn’t recognize the piece in a blindfold test. I was astonished when Alex Ross reported that, late in life, Boulez admitted in an interview that, back in the serialist years, “We didn’t pay enough attention to how people listen.” It reminded me of a Morton Feldman quote, which I will paraphrase from memory: “Only in Europe do you have these revolutionaries who guillotine anyone and everyone who disagrees with them, and then change their minds.” All the same, I will listen to Pli selon pli this afternoon, and tonight I will drink to all of the great European masters of my youth, and to having outlived them.

UPDATE: As promised, I’m listening to Pli selon pli (1983 BBC Symphony recording). It’s pretty frickin’ fantastic.

UPDATE: Juhani Nuorvala informs me that Sylvano Bussotti is still with us – I’m glad to hear it. His continuing presence does not exert the psychic weight on me that Boulez’s did, and so everything else above still stands, but I’m sorry to have given an incorrect impression. As a friend said recently, “A blog is a blog is a blog. There has to be a different standard for informal writing and real-deal scholarship, otherwise no one would ever say anything.”

Technically Definable, Therefore Existent

Having been unexpectedly drawn into writing here about grid-pulse postminimalism, I’ve decided to publish my most important article on the topic here, because the book it’s in is prohibitively expensive, and I need people to be able to refer to it to see exactly what I’m talking about. It’s from the Ashgate Research Companion to Minimalist and Postminimalist Music, which I coedited with Pwyll Ap Sion and Keith Potter, and the succinct title of the article is “A Technically Definable Stream of Postminimalism, its Characteristics, and its Meaning.” In my introduction to the whole volume, I managed to name 32 minimalist composers; here I named 49 associated with grid-pulse postminimalism. This was a widespread movement, involving composers from Hawaii to Massachusetts and Florida to Seattle, plus several Europeans that I knew of.

Having been unexpectedly drawn into writing here about grid-pulse postminimalism, I’ve decided to publish my most important article on the topic here, because the book it’s in is prohibitively expensive, and I need people to be able to refer to it to see exactly what I’m talking about. It’s from the Ashgate Research Companion to Minimalist and Postminimalist Music, which I coedited with Pwyll Ap Sion and Keith Potter, and the succinct title of the article is “A Technically Definable Stream of Postminimalism, its Characteristics, and its Meaning.” In my introduction to the whole volume, I managed to name 32 minimalist composers; here I named 49 associated with grid-pulse postminimalism. This was a widespread movement, involving composers from Hawaii to Massachusetts and Florida to Seattle, plus several Europeans that I knew of.

One of the pieces highlighted here I’ve realized I’m remiss in not featuring more widely on this blog: Dan Becker’s Gridlock, which is practically the poster-boy piece for this movement. It’s the only piece I can think of whose title even alludes to the grid aspect of this music, and in the liner notes Dan talked about the idea of men thinking in grids while women’s concepts are more fluid (although I am struck by by the fact that 14 of my 49 – 29%, which is high for any classical idiom – are women, and their music is just as likely to be grid-based as the men’s). Written in 1994, Gridlock did not appear early in the style’s history, whose beginning I date to Duckworth’s and Lentz’s works of the late 1970s. But it expresses the purest crystallization of the style’s idea, and I’m temporarily putting a recording up here.

Also, since it fortuitously just appeared, here’s the latest disc of music by a central grid-pulse postminimalist composer, Paul Epstein’s Piano Music played by R. Andrew Lee.

And one other recording: “Alone in a Crowd,” the first track from Jeff Beal’s soundtrack for the movie Pollock, the only film soundtrack I know of which fits perfectly in the grid-pulse postminimalist aesthetic (and the only non-Glass soundtrack I own and listen to for pleasure). That’s a 50th composer. So you don’t know about grid-pulse postminimalism? You can now if you want to, 8000 words worth. And from now on when I refer to the topic I’ll link here.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

A Technically Definable Stream of Postminimalism, its Characteristics, and its Meaning

By Kyle Gann

As scholars, we strive to efface ourselves in favor of the phenomena we study; as music historians, we shape history, but only after we let the data we take in shape us. Working as a music reviewer in the 1980s and ‘90s, I became aware of a new repertoire of music whose stylistic commonalities were too striking to ignore. The music, mostly American in the concerts I heard, was overwhelmingly diatonic in its scales and harmonies. A grid of steady beats was almost always maintained, often throughout an entire work or movement without change of tempo. Dynamics tended to be monochrome or terraced, with little of the kind of expressive fluidity one associates with music of the Romantic or modernist eras. In its circumscribed materials and emotional staticness (which is not to say the music was unemotive, but rather that it tended to maintain one affect throughout), the music was analogous to certain genres of Baroque music, particularly German and Italian instrumental music of the late Baroque, though using a harmonic syntax that was in no way conventional. One of the most intriguing aspects of this repertoire was that it ranged in typology from highly structured to completely intuitive and every nuance in-between.

From the beginning it seemed clear that this music was on the most obvious level a collective response to the somewhat earlier style known as minimalism. The differences, however, were decisive. Many of the major minimalist works of the 1960s and ‘70s, now too familiar to us to list here, seemed to embody a new performance paradigm. Minimalist works were often evening-length and suited to a listening mode more ambient and less formal than that of the standard classical music concert; audience members might lie down or sit on the floor, and could come and go as they pleased. Instrumentation for these works was often open and variable from one performance to another. The composers sometimes had their own ensembles dedicated to their works alone. The pieces were sometimes not set at a composed length, but could stretch on longer depending on the performance circumstances.

The subsequent repertoire that had imposed itself on my attention represented a return to the conventional classical-music concert paradigm. It was almost always written in standard notation, though with a minimum of expression markings. The duration of pieces returned to the conventional concert-music length of, say, five to 25 minutes. Most of the music was for chamber ensembles or solo instrument, occasionally involving electronic instruments such as guitar or synthesizer, but rarely with much emphasis on electronic timbres. However, certain aspects of minimalist music, in particular the phase-shifting found in Steve Reich’s early music and the additive process of Philip Glass’s early music, were often taken over as structural devices. In minimalist music, these devices are generally meant to be obvious to the listener; it is one of the primary changes wrought by this new repertoire that it used them in a more underlying, even occult manner. Minimalism, moreover, was not the only musical influence. Beneath a patina of stylistic homogeneity, the music made reference to a panoply of genres: Balinese gamelan, folk music, pop, jazz, 18th-century chamber music, Renaissance music, and even national anthems and specific tunes and pieces. It was a remarkably eclectic body of music, ironically so, beneath its seamlessly even surface.

The number of pieces I encountered as a music critic at concerts and on recording in the 1980s and ‘90s that fit all of these criteria was too copious to ignore. Ubiquitous similarities made comparisons inescapable. It was as though an entire generation born in the 1940s and ‘50s (and thus a little younger than the original minimalists) was writing chamber works that were conventionally classical in format, but with harmonies, processes, and textures inspired by the more unconventional minimalist works that poured from the Manhattan and San Francisco avant-gardes. No survey of 18th-century symphonies could have revealed more striking overlaps and consistencies of style and method.

A word was needed to encompass this far-flung musical language that so many composers were working in. The word postminimalism was floating around, especially among musicians in conversation. Critic John Rockwell was referring to post-minimalists in music in The New York Times at least by 1981 [1], and in 1982 he could start off a review by mentioning, “One hears a good deal about post-Minimalism these days.â€[2] In 1983 he referred to John Adams as a Post-Minimalist, describing the idiom as “a steady rhythmic pulse and a shimmering adumbration of that pulse by the other instruments and voices.â€[3] Just prior to that article and in the same newspaper, Jon Pareles – reviewing composers David Friedman, James Irsay, Amy Reich, and others unknown to me – attempted a capsule definition of postminimalism as “using repetition for texture rather than structure, and embracing sounds from jazz and the classics.â€[4] There is, indeed, a strong continuity between especially this latter definition and the usage I will propose here.

My own earliest use of the term postminimalism, at least in the Village Voice, was five years later on March 26, 1988, in an article mentioning composer Daniel Goode as an example.[5] I made my first attempt at a full definition of the style on April 30, 1991, in a review of the Relache ensemble (perhaps the most important commissioning ensemble for this style of music) performing Janice Giteck, Mary Ellen Childs, and Lois Vierk.[6] A week later critic Joshua Kosman applied the term to Paul Dresher’s music in the San Francisco Chronicle[7], and he later used it to describe Steve Martland in 1994[8], and David Lang in 1995 and ’96.[9] Then, in his 1996 book Minimalists, K. Robert Schwarz mentions that the term post-minimalism had “been invented†(presumably by Rockwell, though he gives no citation) to describe the neoromantic postmodernism of John Adams’s music.[10] At the end of that year, Keith Potter used the term postminimalism in The Independent in a review of the Icebreaker ensemble performing music of David Lang and Michael Gordon.[11]

I supply the exact type-setting of the term in each case to bring out the curious coincidence that those (especially Rockwell) who used the term in these early years to describe John Adams’s music, and also the post-1980 music of Steve Reich and Philip Glass, tended to spell it with a hyphen, post-minimalism (and often with a capital first M). Those who applied the term to younger composers who had not been among the original minimalists tended to use the non-hyphenated form. It is as though, on whatever conscious level, those who described the later music of previously minimalist composers separated the term into post-minimal, emphasizing the connotation of post as after; those who referred to a new style by younger composers applied to it the sleeker, more unified postminimal. From this tendency I will take license, then, for purposes of this article, to use un-hyphenated postminimalism to denote only the repertoire of music whose style characteristics I have described. Perhaps ultimately some further restricting term will be necessary: for instance, “grid postminimalism,†referring to the music’s tendency to place every note on a 16th-note or 8th-note grid and to eschew expressive or expansive rhetorical models of any kind in favor of stepped contrasts (if any). No new musical term is ever introduced without controversy, and there are always those who protest that the mapping of a word to a variety of musical practices is never literal enough. This can’t be helped. I may lack a precise term, but I can define the body of music I venture to write about here with the utmost specificity. I may have to beg the reader’s indulgence for my circumscribed definition, but that the repertoire I describe was a widespread and clearly recognizable idiom of the 1980s and ‘90s can be established by evidence too voluminous to contradict.

Despite the catalogue of similarities that will ensue, I would not want to give the impression that postminimal music was in any way conformist or derivative. Its paradigmatic conventions (due perhaps to whatever personal proclivities on the part of its creators, ranging from a desire to sit in chairs to an lack of interest in hallucinogenics) remained those of the concert hall. Within those conventions, a new musical language appeared in full bloom almost overnight. The valorization of idiosyncrasy has become so prevalent in the arts that we forget how much advantage can accrue from a large number of people speaking the same language. Differences between pieces sharing this language could be subtle and distinctive. Composers working on the same problems could learn from each other and push the language’s evolution to a new level. Listeners were freed from having to confront a new set of expectations from concert to concert and record to record. Continual innovation can be excitingly mind-opening, but development of a common language promotes depth in public discourse.

Not that any of this happened by conscious intention. The first pieces of music that used minimalist harmony and processes in an abbreviated and fully-notated format appeared in the late 1970s from composers who were unaware of each other’s work. I would count, among those pieces, William Duckworth’s Time Curve Preludes (1978-9) and Southern Harmony (1980-81), Daniel Lentz’s Wild Turkey and The Dream King (1983), Janice Giteck’s Breathing Songs from a Turning Sky (1980), Ingram Marshall’s Fog Tropes (1979/82) and Gradual Requiem (1979-81), Peter Gena’s McKinley (1983), and Jonathan Kramer’s Moments In and Out of Time (1981-3).

In addition to these, composers who have written notated music within postminimalism’s diatonic harmonies and grid-like tempo constructs include (in alphabetical order) Thomas Albert, Beth Anderson, Eve Beglarian, Dan Becker, David Borden, Tim Brady, Neely Bruce, Gavin Bryars, Giancarlo Cardini, Mary Ellen Childs, Lawrence Crane, Paul Dresher, Paul Epstein, Graham Fitkin, myself, Peter Garland, Daniel Goode, Judd Greenstein, Jean Hasse, Melissa Hui, Dennis Kam, Guy Klucevsek, Joseph Koykkar, Jeremy Peyton Jones, David Lang, Paul Lansky, Elodie Lauten, Mary Jane Leach, Bunita Marcus, Steve Martland, Sasha Matson, John McGuire, Beata Moon, Maggi Payne, Belinda Reynolds, Stephen Scott, James Sellars, Howard Skempton, Bernadette Speach, Kevin Volans, Renske Vrolijk, Phil Winsor, Wes York, and many others. When this many artists have written music that can be similarly characterized in both technical and contextual terms, to refrain from applying a common terminology would seem like a perversely ideological nominalism. Admittedly, this is clearly a larger repertoire of music than can be even cursorily digested in an article such as this; I select my examples primarily based on relevance to certain generic technical points, as well as based on availability of scores and recordings.

I might add parenthetically that there is another repertoire of music, consisting of the 1940s music of John Cage and the later music of Lou Harrison, Alan Hovhaness, and others, so similar to 1980s postminimalism that I have sometimes jocularly referred to it as “protopostminimalist.†Examples would certainly include Cage’s In a Landscape, Dream, and Three Pieces for Two Prepared Pianos, as well as Harrison’s Serenade for Harp, Koro Sutro, and quite a few other pieces. Since that music was written by composers whose styles were formed prior to the advent of minimalism, it would be misleading, I think, to attempt to include it within the postminimalist rubric. Those works themselves, moreover, were clearly among the several influences on the postminimalist movement.

As the term is used here, a piece of music can be understood as being only partly postminimalist, and there are phases in which we can sense a transitory state between minimalism to postminimalism and between postminimalism and something else. The former is especially clear in works which retain some of the strict processes associated with minimalism: most notably, phase-shifting and additive (or subtractive) process. (Jon Pareles used postminimalism in 1983 to connote “using repetition for texture rather than structureâ€; likewise, we could also say that it uses phase-shifting and additive phrase-lengthening for structure rather than as audible process.) In addition to Piano Phase and Come Out, the phase-shifting tendency can also be traced to Henry Cowell’s book New Musical Resources (1930), in which Cowell suggested basing works on a “harmony of links,†by which he denoted different rhythmic cycles running concurrently and going out of phase with each other.

Strict Process

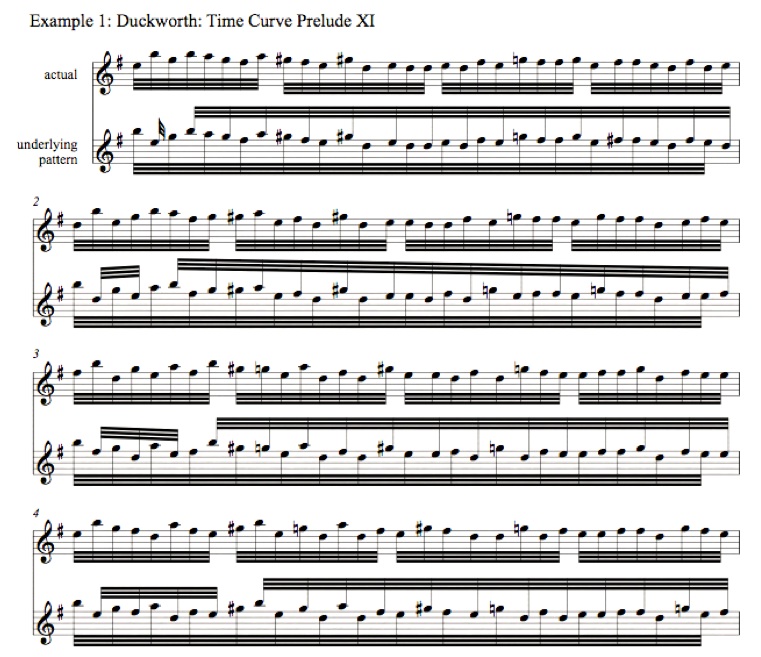

As a seminal example, William Duckworth’s Time Curve Preludes from 1978-79 exhibit, in their 24 movements, a stunning variety of postminimalist techniques, some more transitional than others. Prelude XI, for instance, is one of the examples closest to its minimalist roots. It consists of 15 successive melodies, with occasional rhythmic augmentations and pauses. The relation among the melodies is probably more obscure than any listener could analyze by ear, but it is noticeable on some level that all the melodies use the same pitches, and use them each the same number of times; the not-completely-diatonic pitch set aids this perception, since within the general E-minor mode there are two G-sharps per melody that change their position within each iteration.

Analysis reveals that the melodies result from one 16-note melody (itself based on the shape of the Dies Irae, one of the work’s recurring references) going out of phase with itself. (In Example 1 the unchanging melody is given in the upper octave and the moving melody in the lower octave). Notice – and this is a telling departure from minimalism, ultimately with major consequences – that the process in not carried out with complete strictness. Within each pair of notes, sometimes the moving melody note appears first, sometimes the unmoving melody’s note, and the decisions were made intuitively with melodic and pianistic criteria in mind. And yet the piece is a clear expansion of the idea of Reich’s Piano Phase, with different and less obvious effect.

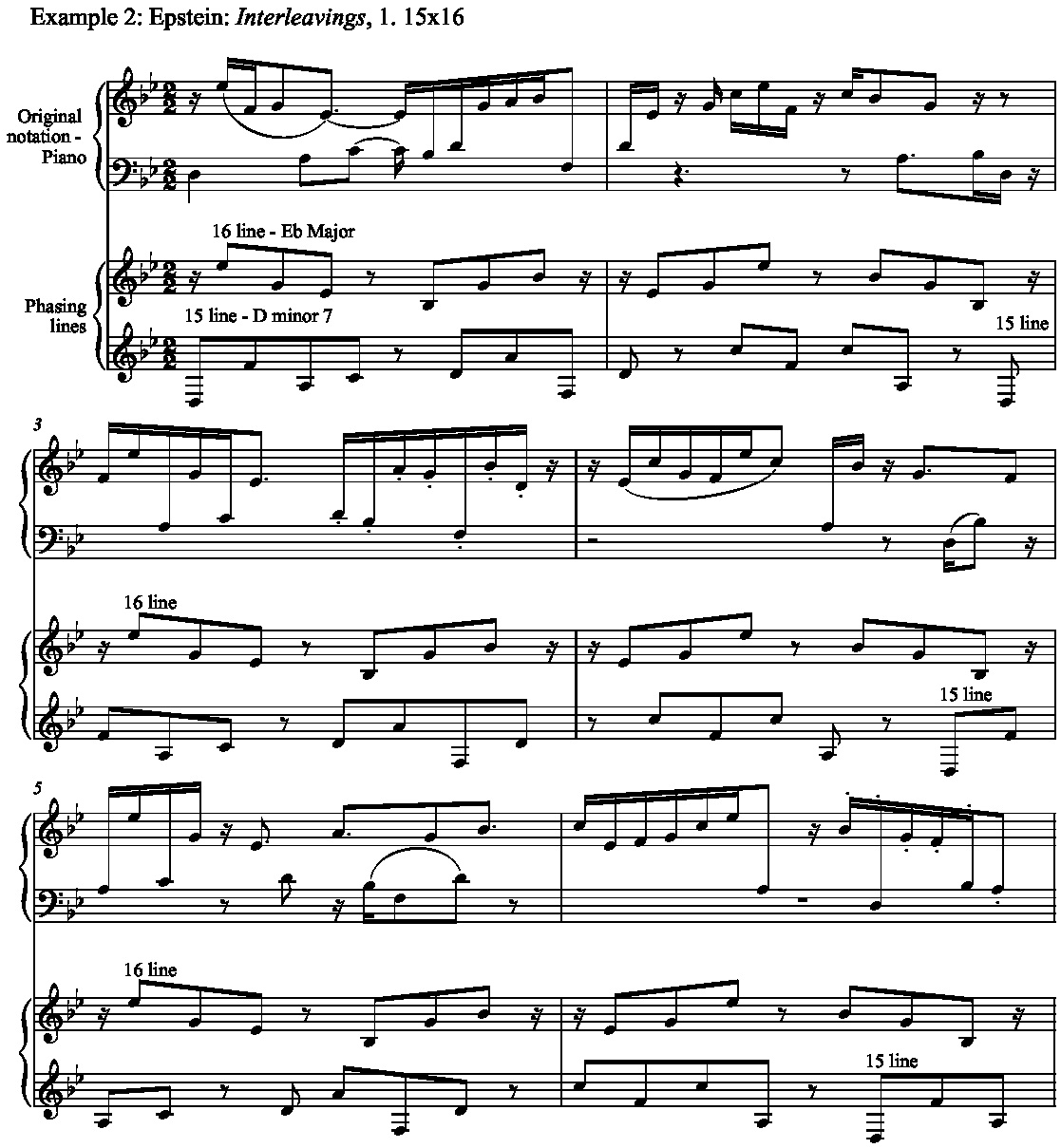

Piano Phase also had a major impact on another composer, Paul Epstein (b. 1938), who wrote a 1986 Musical Quarterly article titled “Pattern Structure and Process in Steve Reich’s Piano Phase,â€[12] analyzing Reich’s opus in great detail, and who subsequently based much of his own composing techniques on the insights involved. The first movement from his much later piano piece Interleavings (2002) is exactly like Duckworth’s Prelude XI in principle. The movement is titled “15 x 16,†and again it is an inscrutable melody that keeps coming back to all the same notes, and similar rhythm patterns, over and over again with some apparent underlying logic that the ear can’t decode. Again, analysis reveals that the overall melody results from two other melodies, one 15 8th-notes long and the other 16, offset by a 16th-note (Example 2). Whereas Duckworth’s Prelude XI phased a melody against itself, Epstein uses two different melodies for a more complex process.

In other Epstein works this idea is tremendously expanded. His Palindrome Variations (1995) for flute, cello, and piano, is entirely based on phase relations in one 12-note, palindromic melodic figure using only five pitches. Within the 6/4 meter this figure gets rotated to every possible position (Epstein calls the version that begins on the third 8th-note Rotation 3, that which starts on the 7th 8th-note R7, and so on), and at any given moment certain pitches are “filtered†out in a given instrument. It becomes audibly clear that the five pitches of that melodic figure are the only ones in the piece, and some underlying logical ordering seems apparent; the attraction of Epstein’s music, for me, is that it makes you think that if you could just listen hard enough you could figure out what the process is, so it irresistibly encourages very close listening. The range of textures and subsidiary figures he achieves with that one 12-note figure as source material is rather dazzling, and, in fact, the chamber version of Palidrome Variations is greatly reduced from a 22-minute version for synthesizer based on the same principle. I like to refer to Epstein as “the Milton Babbitt of postminimalism,†due to the fanatical rigor of his structures.

From the works of Philip Glass postminimalism also inherited a tendency toward additive process, as well as subtractive process. Time Curve Prelude IX uses as its basis a pitch row taken from the bass line of Erik Satie’s Vexations. The row appears first in half notes, then in double-dotted quarter-notes, then dotted quarters, then quarters tied to a 16th, and so on, speeding up geometrically with each repetition until it seems to disappear in a spiraling acceleration. Likewise, the Music for Piano No. 5 of Jonathan Kramer employs both additive process (more in the manner of Steve Reich, keeping the metric unit constant) and subtractive process. The piece opens in 11/16 meter, with only one note per measure, repeating over and over. A second note is added within the measure, then a third, and so on until a steady 11-note pattern is built up. Then, underneath a freer right-hand melody, Kramer begins subtracting notes from the ostinato, also shortening the meter to 10/16, 9/16, 8/16, and so on.

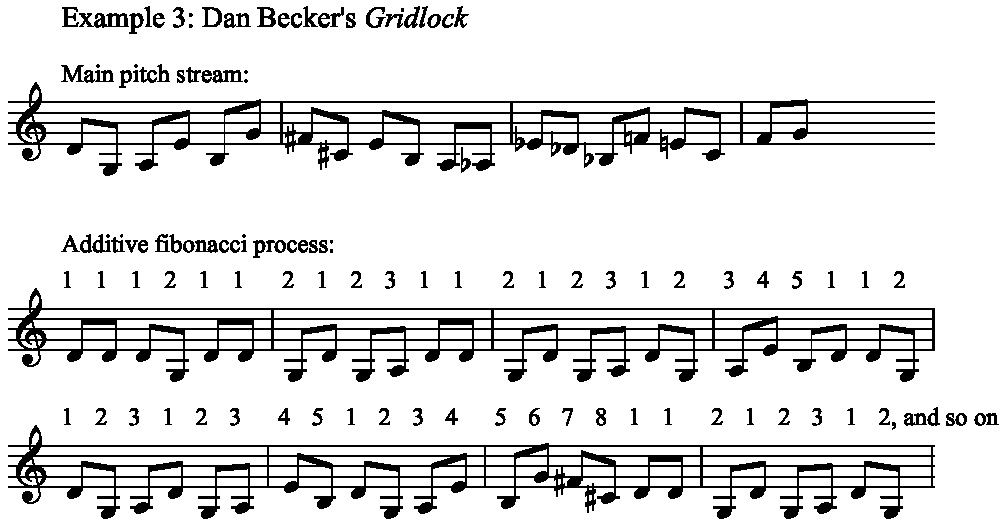

Dan Becker’s Gridlock for mixed ensemble (1994) is a virtual manifesto for postminimalist formalism. Becker mentions in the program note to the piece that he attempted to make a virtue of the “male†tendency (though we will find that women composers do it too) to map out everything onto a grid. The entire piece is drawn from a 20-note sequence (given in Example 3) that roughly traces the circle of fifths. Then, in 16th notes, he additively creates a longer series by taking in series the groups of notes in an additive pattern based on the Fibonacci series: 1, 1, 2, 1, 2, 3, 1, 2, 3, 5, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21 – and then starting over similarly on the second note, later on the third, and so on. The harmony, then, tends to cluster around one area in the circle of fifths for awhile before systematically progressing to another, and the accompanying lines pick notes out from the sequence, with accented rhythms resulting from where certain pitches fall in the 16th-note continuum.

[In case the system seems arcane, the note series is apportioned like so:

1

1 – 1 2

1 – 1 2 – 1 2 3

1 – 1 2 – 1 2 3 – 1 2 3 4 5

1 – 1 2 – 1 2 3 – 1 2 3 4 5 – 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8

and so on.]

My own works frequently use phase-shifting as an underlying principle. My orchestra piece Desert Song (2011, based on a 2006 piano composition) is grounded on an ostinato 83 beats long, interrupted by an orchestral tutti every 149 beats; certain foregrounded melodic elements recur at equally regular intervals. I had been interested in this type of structure ever since my piece for soprano and mixed ensemble Satie of 1975, in which lines went out of phase with each other within a C-major scale, with the additional structural principle (known to British bell-ringers as a “change-ringing†pattern) that pitch dyads within each phrase would be switched in the next phrase: ABCDEFG, BADCFEG, BDAFCGE, and so on. (I later learned that similar patterns were also used by Jon Gibson and Barbara Benary.)

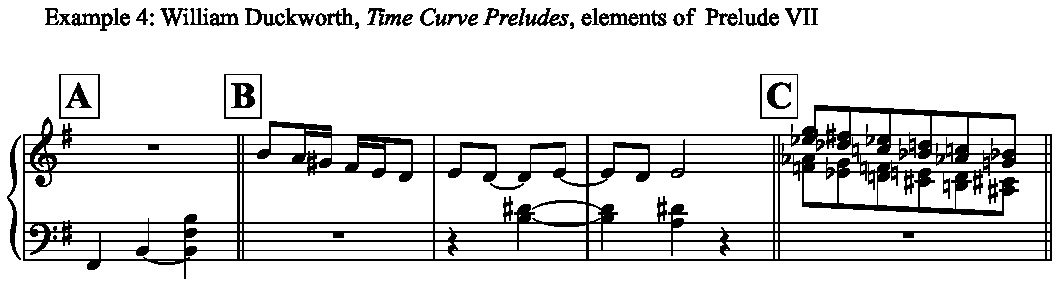

While the minimalist roots of these strict-process pieces are quite evident, much, perhaps most, postminimalist music is not so highly structured. It is one of the features of the style that strict process and free composition can coexist in the same composer’s output, and indeed within the same work; the Time Curve Preludes are a telling example. In Prelude No. VII we find a trace of additive process, but a freer overall structure. This languorous dance is made up of only three elements: a slowly arpeggiated bass line whose final dyad sometimes gets extended (A); a melody that here and there breaks the continuity (B); and a set of six chords that create an impression of bitonality by wandering conjunctly through scales from various keys, though the lower two lines are not actually diatonic (C) (Example 4). There is some inheritance from Glass’s additive minimalism here in the systematic way the phrase lengths expand at first according to lengths proportional to the Fibonacci series, but even this structural element recedes as the B melody intrudes more and more.

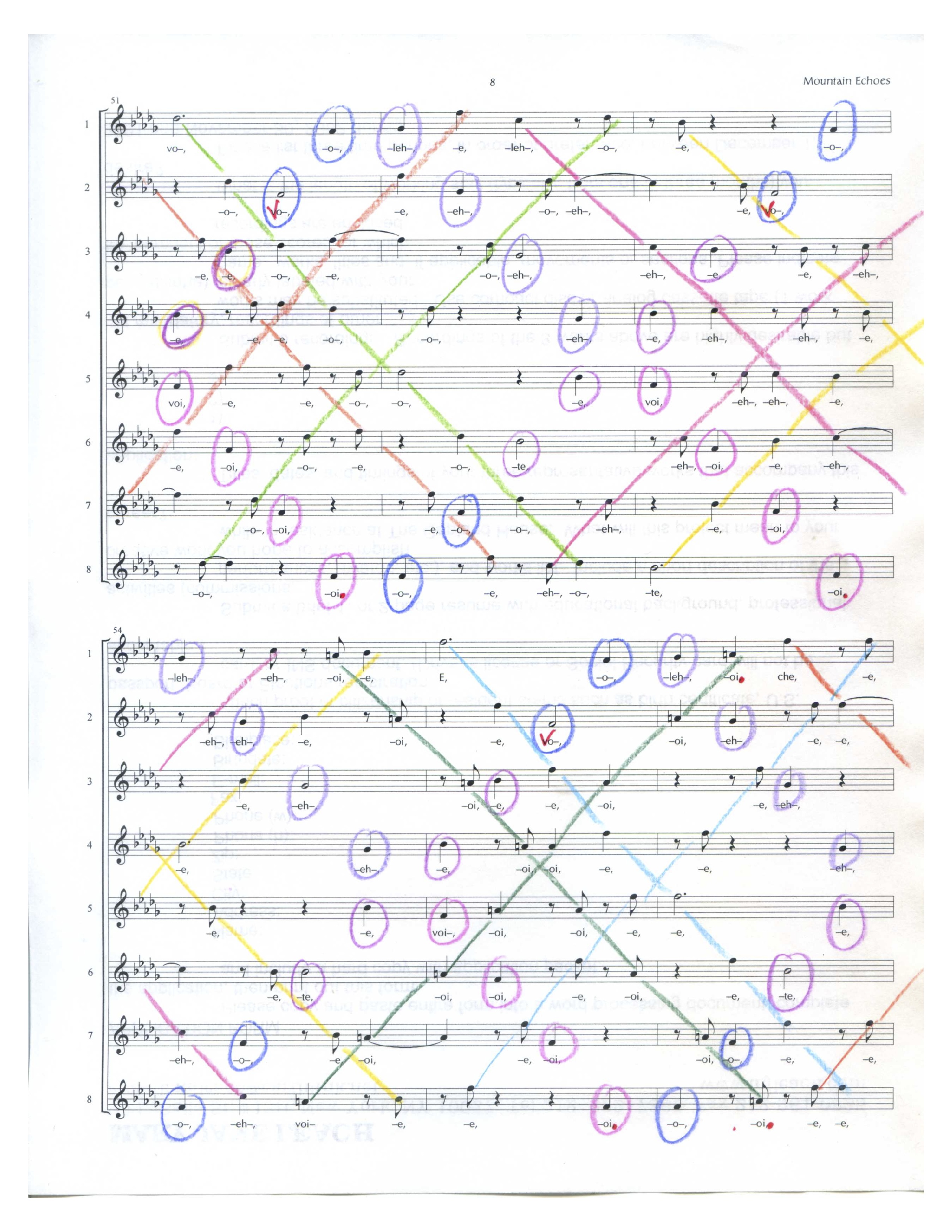

Mary Jane Leach’s Mountain Echoes (1987) is based on an evolving strict process. The music, written for eight female singers staged in two square configurations, opens with a single pitch echoing from singer to singer, from singer 1 to singer 8 and back again. Other pitches are introduced, and gradually new echoes start up on new beats, until, within each two-measure phrase, three pitch-echoes start with singer 1 and three more from singer 8 (Example 5). Other pitches, increasingly echoed, fill in the gaps between the main echo lines as they cross the texture. At maximum density in this process, all the pitches are echoed at a quarter-note delay. Gradually Leach begins omitting pitches until two different lines of echoes are moving in a double braid, from singer 1 to 3 to 5 to 7, and from singer 8 to 6 to 4 to 2. Step by step the melodic lines expand in length, and so do the echo distances, from 4 beats to 5 to 6 to 8. The entire pitch content remains on a seven-pitch, non-diatonic scale within one octave: F, Gb, Ab, A, Bb, C, Db, F. The process, taking eleven minutes, sounds deceptively strict and at certain moments repetitive, and is impossible to disentangle by ear, creating a sense of mystery.

Quotation

For whatever reason, quotation of other music and styles is common in this vein of postminimalism; the style’s unvarying tempo and adaptability to any repertoire of harmonies seem to invite the abstracted, sometimes ironic or playful quotation of earlier tonal music. Leach’s Bruckstück (1989), for six female voices, slowly works its way though the opening harmonies (plus a few melodic motives) of the Adagio from Bruckner’s Eighth Symphony – assuming the singers perform their rhythms accurately, one might even pick that fact up from the pulsing of the opening multi-voice drone on Db. The music proceeds in rhythmic ostinatos which change every few measures, inflecting the pitches to move from, say, the opening Db minor triad to a German sixth chord to the unexpected (in both Bruckner and Leach) key of B major. The Time Curve Preludes are partly unified by the quotations that recur in various movements, including the Dies irae chant and the bass line of Erik Satie’s Vexations, as well as references to bluegrass banjo style and the piano style (greatly abstracted) of Jerry Lee Hooker. Likewise, Belinda Reynolds’s Sara’s Grace for orchestra (1999) is couched in a fully-notated and slightly restrained boogie-woogie style, and is largely based on the old hymn “Amazing Grace,†reworked into 4/4 meter from the original 3/4. Thomas Albert’s A Maze with Grace of 1975 is another postminimalist piece based on the same hymn.

Eve Beglarian’s The Marriage of Heaven and Hell (1994), for voice and mixed chamber ensemble, is a setting of texts of William Blake, including one of his “Proverbs from Hellâ€: “You never know what is enough unless you know what is more than enough.†Just before this text enters near the end, a four-note ostinato begins in the piano and bass and repeats 150 times: Eb-F-G-A. These are the first four notes of Bach’s chorale “Es ist genug,†“It is enough.†The piece smoothly segues, in its final measures, into a quotation of the entire chorale. A similarly scored piece, The Bus Driver Never Changed His Mind (2002) makes reference to the diminished seventh chords of Mahler’s Second Symphony – because the text includes the words “Keep going,†used also by Luciano Berio in Sinfonia, which is based on the third movement of that symphony.

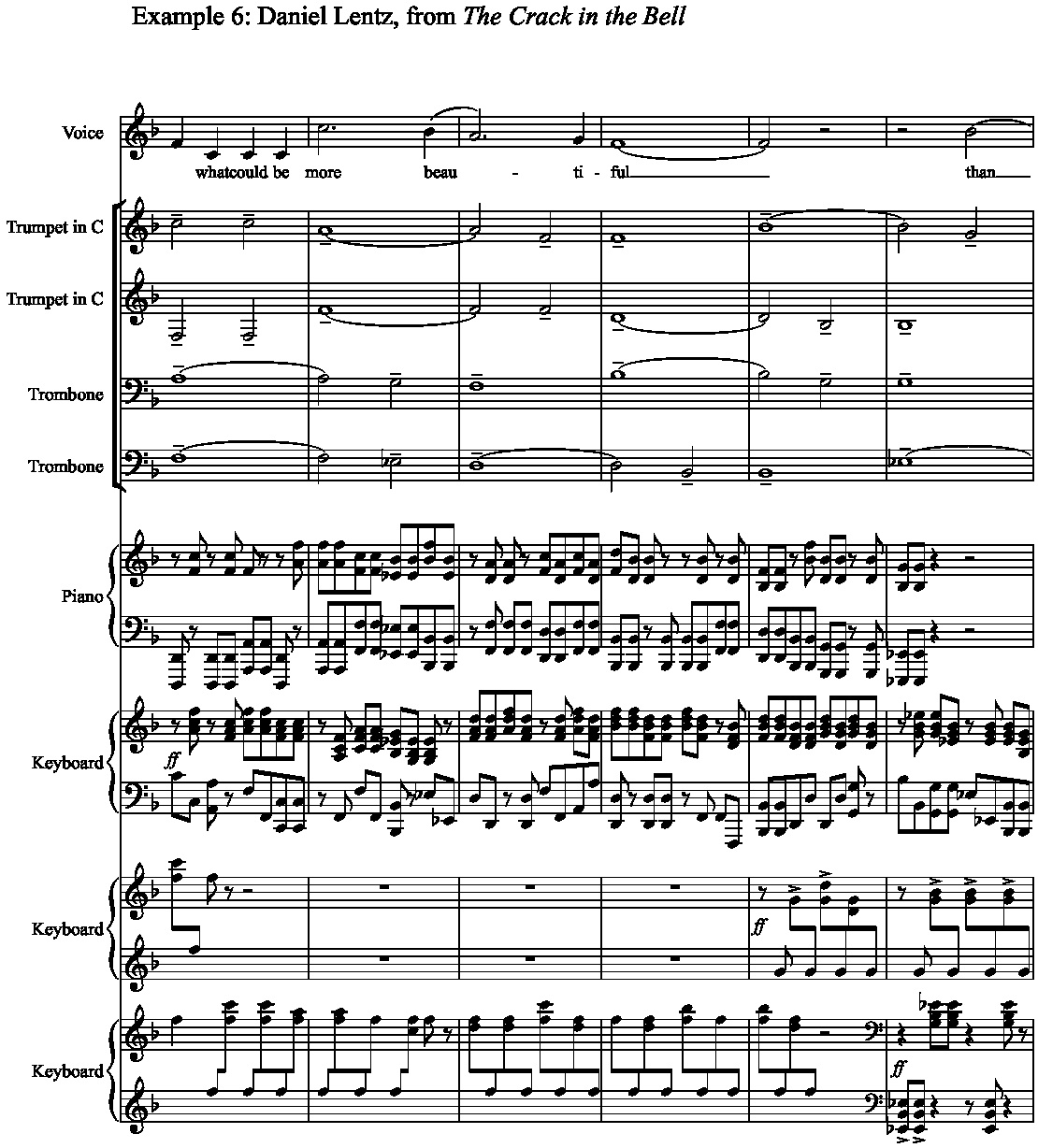

The most quotation-prone postminimalist is Daniel Lentz, whose music is wilder and more wide-ranging than that of any other composer mentioned here. Scored for female voice and orchestra with multiple electric keyboards and digital delay, his The Crack in the Bell (1986) is an extended setting of E.E. Cummings’s poem “next to of course god America i.†On the lines “oh / say can you see by the dawn’s early my / country ’tis of…â€, Lentz quotes, in the voice, the melodies of both the songs referred to. (Duckworth, in his Music in the Combat Zone of the same year, uses the same poem and does the same thing.) More unexpectedly, though, where Cummings mentions beauty (“why talk of beauty what could be more beaut- / iful than these heroic happy deadâ€) Lentz works two passages of pure Renaissance counterpoint into his bouncy, repeated-note texture (Example 6). Certain parts of the piece apply digital delay to the voice and keyboards, so that the repetition of phrases builds up to a texture thicker and more layered than the notes sung and played in the score.

Lentz’s WolfMass (1986-7) is perhaps the biggest quotation bonanza in the postminimalist repertoire; the collage-like Credo contains bits of Machaut’s “Ma fin est mon commencement,†the “Battle Hymn of the Republic,†“Yankee Doodle,†“Battle Cry of Freedom,†“Johnny Comes Marching Home Again,†“Off We Go into the Wild Blue Yonder,†and “America the Beautiful,†with many of the lyrics altered or replaced with the Latin mass text, all more or less smoothed into Lentz’s trademark repeated-chord textures.

Limitation of Materials

Moving further along the continuum from the strict to the intuitive, we find postminimalist works devoid of any strict process but greatly limited in their materials. The fourth movement of Janice Giteck’s Om Shanti, couched in a pelog gamelan scale and audibly indebted to gamelan music, revolves around a continuous melody in steady 8th-notes that runs through the piano and clarinet for almost the entire duration of the movement. The melody’s limitation to the notes E, F, G, B, and C creates an impression that the melody must be repeating or systematically permutative in some way, but it fact there is no repetition at all of any phrase longer than five notes, and no systematic transformation. Likewise, the accompanying stately, slower melodies on those notes in the voice, flute, and vibraphone come back over and over to the same motives, but without any “left-brain†arrangement, entirely intuitive.

What such works reveal as the essence of postminimalism is its reliance on a small, circumscribed set of materials. The second movement of Peter Garland’s Jornada del Muerto (1987) is an extreme case. The entire movement employs only five chords in the right hand, with no transpositions or octave displacements, plus the pitches B, D, and E in the left hand, usually as octaves, and in one section as single notes. No process or continuity device informs this music; it is entirely and intuitively melodic in conception, if chordal in execution. Yet despite its extreme paucity of material, this lovely five-minute movement goes through seven sections touching on four different textures and rhythmic styles, undulating between two tempos. Likewise, the first movement of Garland’s I Have Had to Learn the Simplest Things Last for piano and three percussionists (1993) goes through nine varied sections using only triads on B-flat, C, D, F, and G as its only harmonic material.

This aspect of postminimalism in particular is hardly limited to American works. Kevin Volans’s Cicada for two pianos (1994) is a tour-de-force of limited materials. The two pianists alternate chords in each hand throughout, each chord almost always immediately echoed in the other piano. The entire piece takes place on a scale Bb, C, C#, D, E, F, G, A, with a low F as a bass drone and Bb heard as a tentative tonic. There are subtle exceptions: in m. 53, less than halfway through the piece, an Eb is introduced, and Bb is momentarily the lowest note; at four points, in m. 114 (just past the halfway point) and mm. 150, 155, and 174, the chords are interrupted by a single line of notes in mid-register. Top notes, perceived as the melody, are restricted to D, E, F, G, and A. The piece is not quite in a single tempo throughout, as the phrases weave subtly among tempos of 138, 126, 112, 108, 120, 96, and 132 to the quarter-note, a small repertoire of recurring tempos. The single-note sections are considerably slower. Many of the phrases, bound on each side by brief pauses of varying lengths, are repeated as many as eleven times. Dynamics range, by phrase, from ppp to mf, and in a couple of places are differentiated between right and left hands. There are no landmarks in this lovely 25-minute continuum, no way to form expectations except that the sonority with its undulating scalar melody, will continue, ever unpredictable in its details.

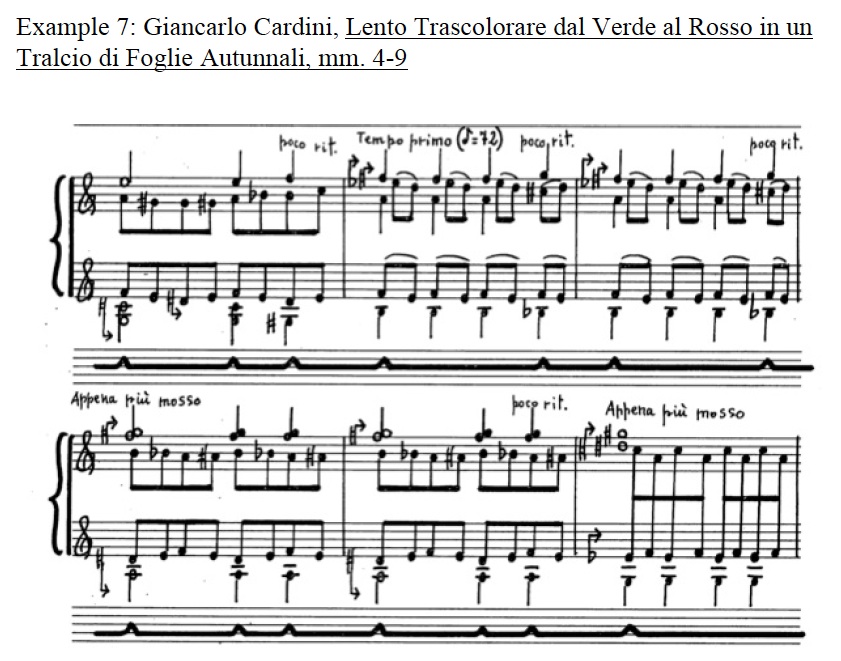

The Serbian postminimalist Vladimir Tosic has written a series of works – Altus for baritone saxophone and piano (2001), Dual for flute and contrabass (1992), Varial for piano (1990), Voxal for piano and strings (1995) – all based entirely on what might be called an “overtone scale†[or Lydian dominant] based on C: C, D, E, F#, G, A, B-flat, B. All four pieces remain within an uninflected 16th-note grid. Voxal, in particular, has the pianist play a moto perpetuo of up-and-down arpeggios over which the strings move limpidly among phrases that add and subtract pitches one at a time: GCD, GDF#, GBbF#, ABbF#, ABbE, ABE, CBE, CB, C, CD, and then repeating the progression. The Italian composer Giancarlo Cardini has written piano pieces that move among recurring harmonic or arpeggiation figures, often with a steadily flowing 8th- or 16th-note motion. His Lento Trascolorare dal Verde al Rosso in un Tralcio di Foglie Autunnali for piano (“Slow Change from Green to Red in a Bough of Autumn Leaves,†1983) is based almost throughout on undulating alternations of 8th-notes with a slowly changing harmony, giving way to quarter-notes and finally half-notes at the end (Example 7).

Duckworth’s music at times seems to use limitation of materials to explicitly mimic a strict background structure. Time Curve Prelude No. 15 takes place entirely within a non-diatonic seven-pitch scale: Eb, F, F# (or Gb), G, A, Bb, D. A sense of shifting tonality is created by switching back and forth between drone pitches Eb and D in the bass (stabilized by their fifths, Bb and A). When the drone is on Eb, the melody seems to be a Lydian scale with a major-minor ambiguity; when on D, it seems to be a quasi-Arabic scale with a flat second and major third. Given the Fibonacci structuring of many of the Preludes, and a free tendency toward subtractive rhythm at the end of the piece, one is tempted to assume that the drone pitches are outlining some predetermined structure, but analysis shows that this is not the case. Where some of the Preludes obscure a strict precompositional pattern, this one seems to point to a precompositional pattern that is in fact not there.

One could say something similar about Dan Becker’s Fade for flute, piano, vibraphone, and cello (2003). The piece starts in a diatonic scale with three sharps, moving by stages to two sharps, one sharp, and then after a chromatic transition, to five sharps. Repeated phrases create a sense of gradual process that turns out to be entirely illusory as the piece wends its slowly changing rhapsodic way. Slow transformation is the music’s modus operandi, but each transformation is eventually abandoned for a move in another direction.

Like Becker’s Gridlock, the title of Joseph Koykkar’s Expressed in Units (1989) seems to imply the sense of composing within a grid. The first and last of three movements begin by reiterating melodic/harmonic figures in rhythmically unpredictable arrangements (a Stravinskian strategy as well as postminimalist). One by one, other figures are introduced, and take turns dominating the continuity. The opening figures of the first movement use only the pitches D, E, F, F#, G, G#, and A, with undulating shifts between F and F#, and G and G#, particularly prominent. The first eight pages of the second movement flow entirely within the scale D, F, G, A-flat, B, and C, with other pitches introduced in succeeding figures. The piece is a rather wild rhythmic ride, though loud figures are supplanted by quiet ones for a thoughtful overall shape.

Beth Anderson is an interesting case study, a composer of music so simple and mellifluous that someone unaware that she studied with Cage, Terry Riley, and Robert Ashley might not suspect minimalist influences. Her Piano Concerto (1997, with strings and percussion) uses a steady dotted-quarter beat throughout, in meters ranging up to 21/8 and 27/8. Flowing melodic figures and rhythmic ostinatos recur with an almost stream-of-consciousness insouciance, often with long periods of static harmony; the key signature is mostly two sharps, but some passages suggest A mixolydian mode more than D Major. One could almost suppose that the work was an early-20th-century British composition based on English folk song sources, a sign of how easily postminimalism can approach more naïve earlier historical styles.

Anderson’s breezy Net Work for piano (1982) is more process-oriented, but playfully unstrict. The opening spells out chords in a thirds-descending sequence on A, F, D, Bb, G, Eb, E, and back to A, after which a simple, syncopated theme arrives. The theme then appears in a succession of all of these keys, going through them twice with variations of meter and rhythm, and then modulating through the same keys again phrase by phrase. She also has a series of pieces called Swales, denoting a kind of meadow in which many different kinds of flowers grow, and marked by an almost stream-of-consciousness technique within very simple tonalities. Rosemary Swale (1986) for string quartet, for instance, is almost entirely within the A natural minor scale, with a few isolated patches of chromaticism.

Although Robert Ashley’s operas are hardly postminimalist, he often bases his works on a quasi-minimalist structure, and resorts to a classically postminimalist style in his late instrumental works. One such work is Outcome Inevitable (1991), scored for the Relache ensemble (flute, oboe, saxophone, bassoon, electronic keyboard, percussion, viola, and bass). The piece is grounded in an insistent repeating middle C in the bass, in constant 16th-notes. The structure is set by repeating rhythms tapped out softly on a bass drum in odd groupings; first a 7+10 pattern (counted in 16th-notes), then 3+3+3+3+5+3+5, and so on. Because the number of 16th-notes in each pattern is odd, the repetitions have to occur in multiples of 4 so that the section will end at the end of a measure. These rhythms create a seven-part structure, each part of which accompanies a solo by a different instrument:

The oboist doubles on English horn, the clarinetist on soprano sax, and the flutist on alto flute.

The melodic aspect of these solos is simple in concept, and beautiful to follow. Almost all of the melodies consist of rising scales interrupted by occasional leaps (or steps) downward to keep the line within a fairly narrow range. Each phrase consists of a number of 16th-notes (from 0 to 6) leading to a sustained note. The sustained notes last durations divisible by a dotted quarter note, from 1 to 7. The sustained notes are also accompanied by chords in the electric keyboard, and “shadowed†by a note in the viola that starts in unison in the first section and moves a step further away in each section. Lasting 16 minutes, the piece is a lovely evocation of timelessness, drawn from a clear and endlessly elaborated idea, but quite unpredictable in its details.

Some of my own microtonal pieces use a limited repertoire of chords partly to keep the number of pitches from getting out of hand. Charing Cross (2007), for instance, for electronic instruments, uses only six chords on the 1st, 7th, 9th, 11th, 13th, and 17th harmonics of C. A simple, quasi-pop, eight-beat ostinato runs through the work, increasingly altered in rhythm by subtraction of beats.

In certain postminimalist pieces we hear the style begin to bleed into something else. The first 25 measures of Belinda Reynolds’s Cover (1996) certainly seem to be those of a postminimalist piece. Again, only six pitches are used – E F# G A# B D# – with E in the piano as a low drone note, and a certain obsessive reiteration of characteristic figures, particularly the competing fifths E-B and D#-A#. However, the music crescendoes to a sudden new chord at m. 26, and subsequently every few measures the music ups the energy by shifting to a new scale. There might be no reason to call this curvaceous, quasi-organic piece postminimalist except that, within each “moment†(to use the Stockhausenesque term), it tends to build up pitch sets and melodies additively, starting as an undulation of two notes and adding in others, almost like a memory of minimalism. Ultimately, Cover‘s form is not postminimalist – there are no more implied limitations on where the music could go than there are in Mozart (fewer, in fact) – but its technique is. One of the advantages of defining postminimalism (or any style) in terms of its central idea is that we can treat the style itself as an ideal form, and talk about degrees to which a particular piece participates in that style. Just as Time Curve Preludes lies slightly on one side of postminimalism, coming from minimalism, Cover is a piece evolving from postminimalism and leaving it behind toward something else, but with its origins still much in evidence.

So insistent is this grid-rhythmed, diatonic, flat-dynamic paradigm in minimalist-influenced (but not conventionally minimalist) music in the quarter-century following 1978 that the observer and listener is tempted into a realist, as opposed to nominalist, position: that postminimalism, in this specific definition, was not simply a set of qualities drawn from a widespread coincidence of occurrences in a diversity of pieces, but virtually a self-contained paradigm inspired by minimalism in many minds, and which became instantiated in hundreds of different pieces. This is not in the least to imply that those pieces are identical in meaning or content, any more than a group of 18th-century symphonies are identical, but that some ideal style conception seems to have occurred to many minds in the same period of time.

As a critic I also noticed a difference between what I am calling postminimalism and another style, also with an inheritance from minimalism, that has been called totalism. Totalism is a more rhythmically complex style, and its harmonies are often more dissonant. In certain works and with certain composers, postminimalism and totalism can bleed into each other; in particular the music of John Luther Adams seems to straddle the two styles, and I myself have written examples of both genres. For me, postminimalism is distinguished by the feeling of a unified rhythmic grid in a consistent tempo, whereas totalism is characterized by a feeling of different tempos superimposed in layers. The music of John Luther Adams is often characterized by the diatonic pitch language of postminimalism with the tempo layering of totalism, though (unlike in the totalist music of Michael Gordon and Art Jarvinen, for instance) the temporal dissonance is not always perceptually obvious. In short, there is no real line separating postminimalism from totalism (just as there is no strict divide between minimalism and postminimalism), though most of the composers involved tend toward one style or the other.

What It All Means

So what, in this restricted definition I’ve given, does (“gridâ€) postminimalism mean? More precisely, what does it say about the world? What is implied in the act of limiting one’s materials and creating a structure that doesn’t step outside its opening parameters? Why did this particular form of expression come to appeal to such a diverse group of composers in the 1980s?

First of all, postminimalism was an explicit acknowledgement that, as Stravinsky put it, “All art is artificial.†(In certain areas of postminimalism, particularly among Dutch composers, the Stravinsky/minimalist influences seem inextricably mixed.) Throughout the Romantic and modernist eras in the history of music, the sonic means employed expanded in diversity and scope, and early minimalism, with its drones and tape loops, continued, in a sense, that expansion, if along a narrow plane. The phenomena minimalism asked us to attend to, such as slow phase-shifting, expanding form, and unintended resultant acoustic effects were genuinely new to composed music. Postminimalism, on the other hand, advanced no such claims. It constituted an equally radical and more arbitrary reduction of means, to a repertoire of harmonies and rhythms whose contingency, or arbitrariness, seemed all the more palpable in contrast to the former modernist abundance. The limitation of postminimalist music to a handful of chords, or a certain scale, and an unchanging tempo constitutes a negation of the common expectation that the music will evolve freely, that sudden inspirations will change its course, that it will move toward points of tension and release. The inspiration for the piece is perceived not as moment-to-moment, but as global, the materials of the work seemingly conceived as a whole rather than as a linear thought process.

A postminimalist piece seems self-contained, not pointing outward; the references to other music sometimes contained therein are cut off from their source, preserved in abstract notes but not in emotional content, like a fly preserved in amber. It’s as though the composer has made a small universe, the way a mathematician will set up a problem with only a few chosen variables in order to illustrate a larger point. Given the small number of variables, some sort of logic is almost necessarily evident to the listener; it is all the more ironic, then, that postminimalist music so often hides its logic just beneath the surface, creating a slight air of mystery within an otherwise fairly transparent musical environment. We are given only a circumscribed fragment of the musical universe to work with – and even within that truncated segment there is more going on than our ears and minds can account for. This in itself is a metaphysical statement, and a very different one from that embodied in classic minimalism. The world, postminimalism seems to tell us, is understandable, but our perception is so limited that it (our perception) is easily overwhelmed by the interaction of even a few restricted elements and processes. Described this way, postminimalism is a denial of a kind of widespread musical realism, the conceit that music is a metaphor for consciousness, ever capable of self-renewal. It asserts that the part can stand for the whole, that in the behavior of a few restricted elements we can hear the behavior of music itself, and in a context all the clearer for its limitations. The listening process elicited suggests that, while we cannot understand reality in all its complexity, we can begin (at least) to make sense of the world in small bits. In this sense, postminimalism might be cited as an artistic analogue of the “ordinary language†school of philosophy exemplified by John Wisdom, Stanley Cavell, Richard Fleming, and others.

Another, perhaps more practical, way to characterize postminimalism is negative: it was the exact antipodal opposite of serialism. Like the serialists, the postminimalists sought a consistent musical language, a cohesive syntax within which to compose. But where serialist syntax was abrupt, discontinuous, angular, arrhythmic, and opaque, postminimalist syntax is often precisely the opposite: smooth, linear, melodic, gently rhythmic, comprehensible (as to materials, if not always as to process). The postminimalist generation, most of them born in the 1940s or ‘50s, had grown up studying serialism, and had internalized many of its values. Minimalism inspired them to seek a more audience-friendly music than serialism, but they still conceptualized music in terms familiar to them from 12-tone thought: as a language with rules meant to guarantee internal cohesiveness. (One might note, as contrasting recent compositional trends, both totalism and the “New Romantic†postmodernists like Bolcom and Rochberg, whose music throws the idea of cohesiveness to the winds.)

Additionally, or to put the same point in other words, postminimalism’s style of hard, clean lines, often with a jumpy and/or propulsive rhythm, made a welcome contrast, in the early 1980s to serialism’s cloudy and heavily nuanced textures, and without risking the sense of boredom that many listeners found in minimalism. It was simply an excitingly new style at the time.

Beyond that, postminimalist works offer a wide variety of expression, particularly depending on how strictly structured they are, and in what parameters. A postminimalist composer can intuitively write a piece with materials so limited that some background logical procedure seems evident; he or she can start out with a strict background structure and then obscure it with surface detail; or he or she may create a strict logical structure so nonlinear that while its presence can be intuited, it can’t be analyzed by ear. Dan Becker, for instance, characterizes two approaches in his music: “1. Pieces with a bunch of strict processes that I then ‘intervene’ in and try to ‘humanize’ by coloring and sculpting and adding directionality. 2. Pieces that are initially very intuitive, even improvisatory, where I then try and ‘inject’ some structural support by overlaying different (usually rhythmic) processes onto the music.â€[13]

Highly structured postminimalist works, like those of Epstein and sometimes Duckworth, can seem like brain-teasers; they hide a half-evident logic just below the surface and dare the ear to parse it and start anticipating what might happen. In less highly structured postminimalist works the effect can be equally mystical, in a different direction. Creating a through-composed, intuitive structure with only three or five elements (as in Cicada, or Peter Garland’s works) evokes a kind of spiritual virtuosity. “Look what I can do,†it says, “look how long I can sustain musical interest without needing to add anything; look how much variety is already possible with only the most modest means.†Once I asked La Monte Young why the five movements of his early string quartet On Remembering a Naiad all used the same material, and after a second’s reflection he responded, “Contrast is for people who can’t write music.â€[14] Postminimalism seems an extension of this cantankerous sentiment.

In fact, I think that postminimalism staked out a pleasant halfway position between minimalism and the repertoire of music encompassed by both serialism and chance techniques. In certain classic minimalist works (Come Out, Piano Phase, Music in Fifths), the analytical left brain could quickly figure out what was going on, and quit analyzing, as the right brain enjoyed the unexpected perceptions. In John Cage’s change-composed music (Music of Changes, for instance) and certain complex serialist works (Le marteau sans maitre, Gruppen) either there were no phenomena that could be analyzed by the left brain at all, or the underlying structures were so complex that no aural analysis was possible without the aid of the score and some knowledge of the techniques involved. Moreover, in conventional classical music of the 18th and 19th centuries, left brain and right-brain phenomena tended to go hand in hand, so that both sides of the brain were equally entertained.

In postminimalism, however, either the ear can tell that there is some underlying logic, or some underlying logic is suggested by the limitation of materials or gradual transformation; but either that logic is usually not entirely accessible to left-brain analysis, or turns out to be a deliberate illusion. The left brain remains involved, hoping (perhaps) to figure out the underlying pattern, but the ear is more often left with a sense of mystery, enjoying the opaque process without being able to pin very much down. It’s a pleasant listening mode, because without some left-brain involvement, many listeners will simply become bored (as many do, with serialist and chance-composed music); but the right brain, once well engaged, loses any sense of time, and becomes wrapped up in the energy or atmosphere. This is why it seems so significant that there are postminimalist works – the Time Curve Preludes and Om Shanti are examples – in which strictly structured movements jostle with intuitively written ones, and the ear can’t tell which is which. There is no significant difference, postminimalism tells us, between intuition and arithmetic. Through different paths they come to the same result. This suggests that at the base of our intuition is a kind of arithmetic – and perhaps vice versa.

Attempts to define the principles of this postminimalist repertoire begin to fall apart as we spiral outward to the periphery of the style. But I hope this overview has suggested that, for a time in the 1980s and ‘90s, at least, a large number of composers became fascinated by a certain identifiable paradigm of compositional and listening patterns. I would also like to suggest that this enjoyable repertoire, so common on the concert stages of New York, Philadelphia, San Francisco, and other cities during that period, has been greatly underrated and under-recognized, and is well worth considerable performance and study.

[1] John Rockwell, “News of Music; 1982 Festival to Honor Cage†in The New York Times, October 1, 1981, Section C, p. 24.

[2] John Rockwell, “Avant Garde: Johnson,†in The New York Times, June 13, 1982, Section 1, Part 2, p. 69.

[3] John Rockwell, “Concert: New Music of California†in The New York Times, June 6, 1983, Section C, p. 13.

[4] Jon Pareles, “Music: Six at La Mama†in The New York Times, March 6, 1983, Section 1, Part 2, p. 64.

[5] Kyle Gann, , “A Tale of Two Sohos†in the Village Voice, January 26, 1988 (Vol. XXXIII No. 4, p. 76).

[6] Kyle Gann, “Enough of Nothing†in the Village Voice, April 30, 1991 (Vol. XXXVI No. 18, p. 82).

[7] Joshua Kosman, “’Pioneer’ Boldly Goes into Satire†in the San Francisco Chronicle, May 7, 1991, p. E3.

[8] Joshua Kosman, “Steve Martland – Heady and Eclectic†in the San Francisco Chronicle, October 16, 1994, Sunday Datebook, p. 42.

[9] Joshua Kosman, “’Modern Painters’ a Bold Stroke†in the San Francisco Chronicle, August 4, 1995, p. C1; “Kronos Picks Up a Theater Credit†in the San Francisco Chronicle, January 14, 1996, p. 31.

[10] K. Robert Schwarz, Minimalists (London: Phaidon Press, 1996), p. 170.

[11] Keith Potter, “Classical Music: Icebreaker; Queen Elizabeth Hall, SBC, London,†in The Independent, December 4, 1996, p. 23.

[12] Paul Epstein, “Pattern Structure and Process in Steve Reich’s ‘Piano-Phase’†in The Musical Quarterly, Vol. 72, No. 4 (1986), pp. 494-502.

[13] E-mail to the author, August 12, 2011.

[14] Comment to the author, 1992.