I found something I liked yesterday in an interview with Robert Wilson:

He eschews “the lie†of naturalism on stage and sees artificiality as “more honestâ€. Hence he was a perfect fit with Lady Gaga, herself a master of avant-garde showmanship.

It nudges me to write about something I’ve been intending to ever since the minimalism conference in Helsinki. Composer Matthew Whittall interviewed me onstage prior to the concert of my music. I forget what he had asked, and this bit I rescued from a Finnish Radio broadcast didn’t include the question, but here is about two minutes’ worth of what I found myself saying. (If you don’t want to listen, I summarize what I said below, so you won’t miss anything. I usually feel the same way.)

Now, keep in mind that when I said postminimalism, I meant the term not in whatever vague way people might use it in, but according to the precise definition I’ve developed in my books and scholarly articles, as having to do with the diatonic, steady-pulse music of William Duckworth, Paul A. Epstein, Janice Giteck, Daniel Lentz, Elodie Lauten, Dan Becker, Belinda Reynolds, Mary Ellen Childs, Mary Jane Leach, Wes York, Joseph Koykkar, and others. From now on I’m replacing it with the made-up term “grid-pulse postminimalism,” because postminimalism has come to mean whatever anyone wants it to mean, and I can’t report on my scholarly research if I can’t refer specifically to that easily characterized repertoire. My new term is intentionally ungainly because I don’t want other people adopting it and distorting it beyond recognition. Miss that point, and you won’t have as clear an idea what I’m saying.

Matthew had started out asking me about quarter-tones, and I think we were bouncing off of the idea of just intonation being more natural than quarter-tones. Like Robert Wilson, I reflexively balk at the idea of anything we do in music being natural (non-artificial), and so I plunged into my own “naturalism is a lie” shtick. Twentieth century music lurched, in my view, from one simulacrum of nature to another. Twelve-tone music was “natural” because it removed cultural associations from the relationships of the twelve pitches and created the basis for an allegedly organic form, the urpflanze. Then John Cage came along and declared chance more natural. Then Steve Reich made tape loops and phase-shifting look like the real natural phenomena. Then the spectralists analyzed natural wave forms and orchestrated them, so they were the ones really doing nature. Another attempted paradigm shift I left out in Helsinki was John Zorn’s, which was not exactly about nature: he claimed that music would have to be very fast and splintered from now on because kids were being raised on such fast video games that their minds no longer worked the same way.

Each case was an implied mandate, with a necessary paradigm shift in tow. One-upmanship reigned: “You based your music on what you thought was nature, but you didn’t dig deep enough, and my new paradigm goes to the heart of what music naturally is!” And the composition world flocks to these prophets. The underlying assumption is that you can’t simply write what you want to write, or what you find delightful – or you can, but no one need pay attention to you – you have to find the underlying logic, the new mandate on which history pivots. The whole mentality is buttressed by the sick classical-music neurosis that classical music is not a communal activity but a series of Great Men, and we’re always looking for the next savior who will take us deeper, some new Moses we can follow.

Although it’s something of a detour, I can hardly steer this argument around the rather obvious fact that the most acclaimed composer of my own generation, of course, is John Luther Adams, whose music is so closely bound to concepts of nature that it can hardly be discussed without bringing in Alaska, ocean waves, glaciers, northern lights, and so on. [UPDATE: I want to add that this seems like a detour because it’s not that John found a supposedly “natural” way to compose, but that he is depicting, or inspired by, nature, which is a very different thing.] I love John and his music dearly; I don’t think I’ll offend him by saying I don’t consider him a significantly better composer than the late Elodie Lauten, whose music is also very dear to me. They both exude an aura of musical spirituality, though Elodie’s music is far more melodic, subjective, personal, memorable in detail. That two composers so equivalent in talent, hard work, and achievement as John and Elodie, though, could come to such vastly different levels of public recognition strongly suggests how much the new-music world privileges that impression of new nature-related paradigms.

Of course, it’s all fiction. My students never find anything natural-sounding about Webern. Cage’s chance works, some of which I consider wonderful, do not really replicate anyone’s experience of a walk in the woods. What I notice most in spectral music is moments of Debussy, when the harmonic series chords (dominant ninths) come in. John’s use of the C-major scale to symbolize snow is clever and heart-warming, but the music wouldn’t have sounded different transposed up a half-step. They’re different ways to draw sound into metaphors for nature, for some objective process in the world, and they’re as good a starting point as any other musical device. But they aren’t inherently any better. Like any other point of musical inspiration, they can only be judged by the results.

One thing I liked about grid-pulse postminimalism in the 1980s is that it jumped off that train and quit trying to out-natural everyone else. It embraced its artificiality. There were no Great Men in the movement, no justifying teleology, no paradigmatic models (like Drumming, Structures, Treize Couleurs du soleil couchant), nothing relevant but what you could hear. Patterns like phase-shifting had been doggedly naturalistic in minimalism; the grid-pulse postminimalists appropriated them as decorative structures to be playfully arranged and discontinued where one wanted. There was no pretense of some objective force that had been harnessed, and to which we must all bow.

And I think that’s why grid-pulse postminimalism, despite the large number of composers involved in it for a couple of decades, despite the beauty and audience-friendliness of the music, never gained a true foothold in the new-music world. It forfeited any claim to objectivity. No one was threatened by it. As I wrote in my book American Music in the Twentieth Century (1996) – Chapter 12 of which, titled “Postminimalism,” was entirely devoted to this important movement – “If Copland, Harris, Barber, and their ilk represented a first wave of American diatonic consonance, postminimalism is the second.” And yet today when I mention postminimalism in this blog, most people take the impression that I mean an entirely different body of music. After a quarter-century of being an expert on grid-pulse postminimalism, and writing about it frequently on this blog since 2003, it seems that even most of the people who read me have no idea what I’m referring to. One of the most fertile and artistically successful movements in Downtown music has vanished down the memory hole (except that Paul Epstein has a new recording on Irritable Hedgehog, which is a nice development).

Many of my readers will have a suave rationale for why I’ve scoped this out all wrong. Some may well write in to say it’s because grid-pulse postminimalism wasn’t any good, but you won’t know about that because those comments will disappear. I’ve thought about this, and written about it from time to time, for almost thirty years. Yet I wouldn’t have brought it up again except for a recent experience I had.

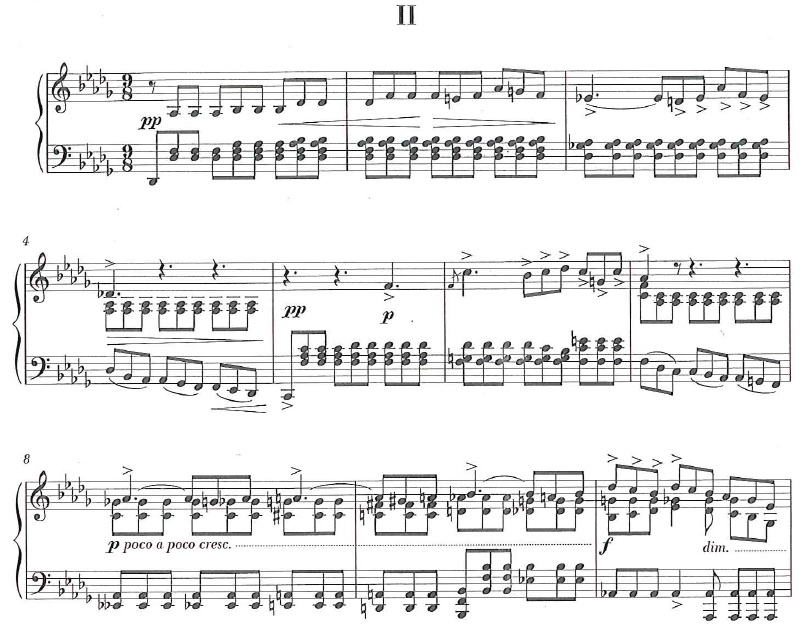

In July and August I wrote a piece for three retuned Disklaviers called Orbital Resonance. Uncharacteristic for me, it’s an entirely abstract piece, with no melodies, no real reference to conventional harmonies, no hooks for the non-musician to hold onto. It sounds granitic and objective, like a piece that just happened. Plus, I had gotten the idea for the rhythmic cycles from the mathematics of planetary orbits, so I had some extramusical source in nature for why I was writing the way I was. As I was writing it, I kept thinking, “Hey, this is the kind of piece that composers will really like, a lot better than they usually like my music.” And sure enough, when I posted it, I got several times as many compliments from composers as I usually get. Composers who had never commented on my music before seemed awed.

I immediately followed Orbital Resonance with another piece for the same medium, Futility Row. Personally, I think Futility Row is a slightly better piece: more subtle overall harmonic structure, better pacing, better development of ideas across the length of the piece. But it wasn’t abstract. There are melodies, and a rhythmic ostinato, and a kind of slightly humorous Western Noir atmosphere. It’s a playful piece, purposely artificial, with no pretense of basis in nature. And I knew composers weren’t going to go for this one. I only got three compliments from composers (and those from people whose taste I particularly trust), though other people have liked it.

Now, I find it entirely significant that I can tell, while composing, that composers will like the piece I’m writing, and when they’re not going to like it, and that it has nothing to do with the quality of the piece. If I were really careerist, I would sit down and write another dozen abstract pieces, pieces that sound more like they just happened than were composed, like Orbital Resonance. It’s a temptation. But I don’t think non-composers automatically prefer those abstract, organic, naturally-occurring-sounding pieces, and I take the long view: I’m trying to reach a widespread audience, not just fellow professionals. This is what I mean when I say, “I don’t write my music for other composers”; what other composers mean when they say it, I have no idea, but everyone says it. Unfortunately, composers run the new-music world, and it’s composers one has to impress to get heard.

What composers value in new music differs from what most people would enjoy in it. They’re looking for a new paradigm, a new Moses, and they don’t want something that’s (as I was told at the ISCM conference in Vienna) “too much written for the audience.” They seem to want something mystifying in its aura of objectivity. As a result they exalt composers like Schoenberg above someone like Poulenc, whose music I’d prefer any day; paradigm-setters such as Stockhausen and Boulez enter history, while those who write more beautiful music, like Maderna and Pousseur, fall by the wayside. In recent years the Times has made the extraordinary gesture of running thinkpieces by composers, and after each one, 90 percent of the comments are people talking about how lousy contemporary classical music is. I hear why they think so; I agree with them most of the time. I think the composing community keeps that rift alive by privileging attributes that are not necessarily virtues. They want to hear the illusion that someone has captured nature in sound. I, like Robert Wilson, am satisfied with the honesty of the artificial.