Oaxaca was a blast. It’s in the mountains and doesn’t get hot, and in the tropics so it doesn’t get cold. The peso is really low at the moment, so we felt like we could buy anything that caught our fancy. The worst meal we had was better than the Mexican food we get at home, and that includes the ones we scarfed down at Mexico City airport. At the best restaurant in town (so we were told), Los Danzantes, we had mezcal margaritas and wine, fantastic mole entrees, and as appetizer I had one of my favorite foods, octopus – not rings of calamari, but a big slab of pulpo with ancho chile sauce. We ate and drank like there was no tomorrow, and the bill for two was $855 – that’s pesos, about 50 American dollars at today’s exchange rates. Other scrumptious meals didn’t even cost us twenty bucks. Waiters were relieved that we gringos could take it as spicy as they could dish it out.

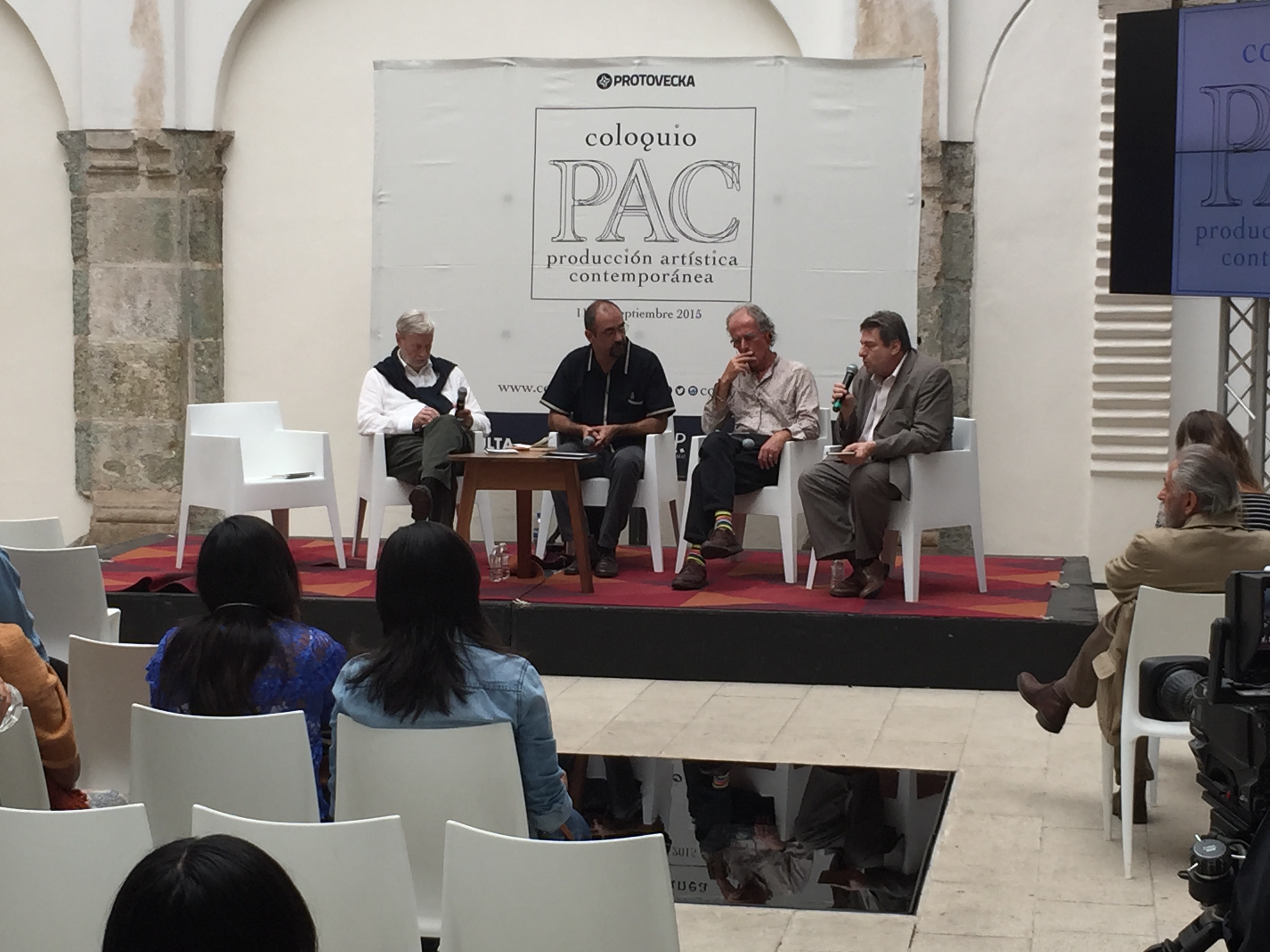

Protovecka, an arts advocacy organization run by Juan Alaya that’s only been around for a couple of years, had invited me and about a dozen other art, film, and music critics for a specifically non-academic conference trying to make connections among the arts. Protovecka and its staff reside in Mexico City, but they kindly decided that the participants would have more fun in Oaxaca. The accommodations were generous, the events well organized, and the refurbished convent in which the latter took place quite lovely. Here are Italian philosopher Gianni Vattimo, music critic and moderator José Wolffer (who knows everything about new music and with whom I had a great time), music critic and prolific author Paul Griffiths, and film critic Richard Pena, colloquy-ing on Sunday’s panel, with expert simultaneous translation for the various languages:

That foregrounded black rectangle is actually a fountain, a thin film of water over a black marble surface, creating a nicely asymmetrical open space in front of one side of the stage. In the U.S., there would have been yellow cones warning people of the danger of stepping on it, but Mexico seems more civilized than that; people are treated like adults.

It’s difficult bringing the arts together these days, and the problems were as I expected, though I applaud the effort. Film is so much part of everyone’s cultural life that the film critics get to live in the real world, even if they endlessly wish that the general public shared their rarefied tastes. The visual arts seem isolated in a self-ratifying loop in which artists, curators, critics, and rich collectors speak a language full of familiar words used in a way that the rest of us hardly comprehend. And the music critics, Paul, José, and myself, share a jaundiced view of how irrelevant (post)classical music has become to the rest of the culture. We struggled gamely to speak the same language (metaphorically) for a few days, and enjoyed each other’s company even when we failed. I was one of only two or three Americans, and it was viscerally comforting to spend a few days conversing with professionals from Mexico, France, Italy, and England, who seem free of the defeatism and pessimism that pervades the U.S. worldview these days. I left with a feeling that things will eventually be all right here, too.

And to get the really long view of cultural change, Nancy and I took a cab (24 bucks round trip) out to Monte Albà n, the mountain site of the center where Zapotec civilization flourished strangely from 500 BC to about 850 AD:

As many as 17,000 people lived in this space at some time, which took us an hour and a half to circumnavigate;Â there were underground tunnels through which priests could run from temple to temple, and an altar for human sacrifices. Certain sites were dotted with carved figures which, when originally discovered by Europeans, were referred to as “the dancers” – Los Danzantes. Turns out they seem to have been portraits of neighboring kings who were castrated and mutilated upon capture:

I guess if the Zapotecs could last here for 1350 years, we Americans can hold on for a few more centuries. Aside from maybe our minimalism conferences where I get to see all my old friends, I can’t think of a cultural event I’ve ever been invited to that I enjoyed more. Next week: Minimalists in Helsinki!

UPDATE: A couple of things. One refreshing difference between this and most of the American conferences I’ve been to lately is that there was almost no mention of critical theory. I didn’t attend every lecture, but only the name Deleuze came up, and only once. There was a lot of talk about Heidegger, whom I’ve read a lot of and took a graduate course in once, and Vattimo mentioned the aesthetician Mikel Dufrenne, whom I read a lot of in college but hadn’t heard of since. So, in terms of intellectual history, I felt rather at home. And it made me wonder if critical theory is only an American obsession.

Also, I always buy Cuban cigars in Mexico, and in every other country I visit. But in Oaxaca I didn’t see a single cigar store, or even anyone smoking a cigar, and when I asked at the front desk, the bewildered employees couldn’t think of anything, and finally located on a map a kiosk in the zocalo. Well, I wasn’t going to go search out a crummy kiosk for a cigar, so for once I came home without any. I was surprised to find that there are places in Mexico where cigars are virtually unknown.