Accordionist Veli Kujala did a lovely job on my piece Reticent Behemoth for his quarter-tone accordion. Here’s the recording from the world premiere last Thursday in Turku, Finland (duration five and a half minutes). I do love the accordion, and Veli made the piece sound more delicate and nuanced than I could have expected. I’m hoping to write him another piece or two.

Archives for September 2015

Strange Bedfellows

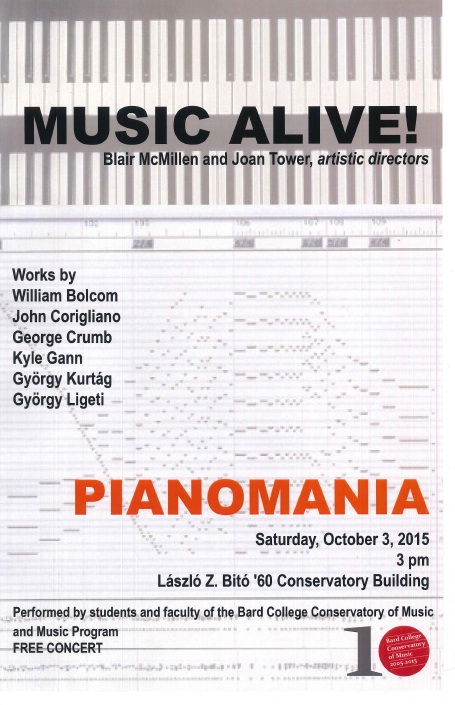

I’ve got a performance coming up at Bard College [where I teach] this Saturday. My office Disklavier will play my Bud Powell homage Bud Ran Back Out, and famous composer Joan Tower, no less, is slated to play the second dance, “Sad,” from my Private Dances. As you can see from the accompanying poster, Kurtág, Corigliano, Ligeti, and I are making a once-in-a-lifetime appearance on the same program. If it weren’t for Crumb and Bolcom I’d feel a little out of place. The MIDI graphic on the poster is a section from my Nude Rolling Down an Escalator, taken from my eponymous CD cover.

I’ve got a performance coming up at Bard College [where I teach] this Saturday. My office Disklavier will play my Bud Powell homage Bud Ran Back Out, and famous composer Joan Tower, no less, is slated to play the second dance, “Sad,” from my Private Dances. As you can see from the accompanying poster, Kurtág, Corigliano, Ligeti, and I are making a once-in-a-lifetime appearance on the same program. If it weren’t for Crumb and Bolcom I’d feel a little out of place. The MIDI graphic on the poster is a section from my Nude Rolling Down an Escalator, taken from my eponymous CD cover.

Postminimalism Takes Finland

The Fifth International Conference of Minimalist Music, in Turku and Helsinki (harbor above), Finland, was a smashing success. I ate sautéed reindeer and plenty of herring. We ended up Sunday night with only a few people left in the upstairs bar at the Torni Hotel, with Helsinki in the background (clockwise: my wife Nancy, Kay and Keith Potter, Dean Suzuki, Jonathan Bernard, Patrick Nickleson):

And here we are eating at the Sea Hors Restaurant: Dean, Nancy, Pwyll Ap Sion, Kay, Patrick, Keith, myself, and Jonathan:

A concert of mostly my music, including my Unquiet Night, Reticent Behemoth, The Unnameable, and Snake Dance No. 2, was presented at the gorgeous Music Centre building in the middle of town, its magnificent lobby shown here:

And I gave what I imagine is the first conference paper on the music of Elodie Lauten, whose reputation seems limited to New York; no one seemed to have heard of her. (I’ll put that paper up in this space soon, but it will take considerable reworking for non-oral presentation.) David McIntire spoke on Ann Southam, Frank Nawrot on Julius Eastman, Dean Suzuki on fine British postminimalist Andrew Poppy, Jedd Schneider on the surprising connections between Krautrock and American minimalism, and Dragana Stojanovic-Novicic on Conlon Nancarrow’s (generally negative) attitude toward, yet interesting connections with, minimalist process. Patrick Nickleson gave a fine paper on the curious ontological status of so much minimalist music, that it tends to not be score-based, but finalized by performance or recording, the score often constructed after the fact by someone other than the composer – with Marc Mellits’s Boosey and Hawkes score to Reich’s Music for 18 Musicians as the quintessential example. I told him that was almost my definition of Downtown music.

At the Finnish music panel I wrote down a slew of names of Finnish postminimalists to look up: Petri Kuljuntausta (whom I enjoyed talking with), Erkki Kurrenniemi, Jan-Olof Mallander, Pekka Jalkanen, Seppo Pohjola, Pekka Kuusisto, Adina Dumitrescu, Pehr Hendrik Nordgren, and of course Juhani Nuorvala, who co-directed the conference with John Richardson. None of us could make head or tail of the language. It seems that, despite some early appearances in Helsinki by Glass and Reich, minimalism and its offshoots have gained a foothold in Finland only in the last decade, largely thanks to Juhani’s efforts.

Here, waiting for the bus from Turku to Helsinki, are Justin Rito (whose paper was on David Lang), Joy and Andrew Granade just past him, Juhani with the glasses, and musicologist Robert Fink and wife in the back:

The Sixth International Conference is now tentatively scheduled for June of 2017 in Knoxville, Tennessee, in connection with the Nief-Norf festival run by Andrew Bliss. It gives me something to look forward to. The passage of my life is measured out in minimalism conferences.

Fun with the Finns

I’m off to Turku and Helsinki, Finland, this week where I will be the featured composer at the biennial conference of the Society for Minimalist Music. There will be a concert of mostly my music Saturday night at the Sibelius Academy Music Centre (since there’s “Mostly Mozart,” I’ve always pictured a “Generally Gann” festival), and I am to be interviewed onstage beforehand. It’ll be old friends week, and you can see the conference schedule here. Robert Fink and Jelena Novak are the keynote speakers. I didn’t need to give a paper this year, but I am: “Elodie Lauten as Postminimalist Improviser,” which I just finished today, or at least enough to stumble my way through it. And I imagine I’ll post it here, or at my web site. We have an idea where in the US the next one will be in 2015, and I’ll let you know when it’s official. I think I probably won’t give papers in the future, just go and listen and hang out. I take way too much unnecessary work onto myself.

Hyperrealism: Chamber Music from Mars

You may not have heard of Noah Creshevsky (born 1945), but he is, and has been for decades, one of the most amazing figures in current American music. His music, all electronic as far as I’ve heard, which he aptly terms “hyperrealist,” is a surreal mix of samples, chamber music from Mars. Weird as hell on first listening (and second and third), it nevertheless flows with its own inner logic, and is easily acclimated to. I’ve told him that, if I had the amazing electronic-music chops he has, I’d be trying to do something similar. Perhaps because I just returned from southern Mexico, it strikes me as bearing a kinship to mesoamerican art, very cleanly etched and clear in its intentions yet extraordinarily strange in its shapes and materials. I can’t think of anyone whose aesthetic is more original. He hasn’t received his due because there are so few distribution venues for bizarre electronic music, and because his lifestyle, as he likes to claim, is highly reclusive. Nevertheless, Dennis Bathory-Kitsz wrote a lovely tribute to him in New Music Box several years ago.

You may not have heard of Noah Creshevsky (born 1945), but he is, and has been for decades, one of the most amazing figures in current American music. His music, all electronic as far as I’ve heard, which he aptly terms “hyperrealist,” is a surreal mix of samples, chamber music from Mars. Weird as hell on first listening (and second and third), it nevertheless flows with its own inner logic, and is easily acclimated to. I’ve told him that, if I had the amazing electronic-music chops he has, I’d be trying to do something similar. Perhaps because I just returned from southern Mexico, it strikes me as bearing a kinship to mesoamerican art, very cleanly etched and clear in its intentions yet extraordinarily strange in its shapes and materials. I can’t think of anyone whose aesthetic is more original. He hasn’t received his due because there are so few distribution venues for bizarre electronic music, and because his lifestyle, as he likes to claim, is highly reclusive. Nevertheless, Dennis Bathory-Kitsz wrote a lovely tribute to him in New Music Box several years ago.

So Noah’s newest CD Hyperrealist Music, 2011-2015 is now out on EM records. The first piece on the disc is titled Pulp Fiction, and in it he used samples from my Disklavier CD Nude Rolling Down an Escalator. I think it the best piece on the disc, though not by much, and his use of my rapid piano gestures is extremely flattering, like overhearing myself complimented by strangers. And I obtained his permission to post the piece here, for awhile. You should get the disc, and all his discs, because they’re phenomenal.

Mezcal, Pulpo, and the Long View of Culture

Oaxaca was a blast. It’s in the mountains and doesn’t get hot, and in the tropics so it doesn’t get cold. The peso is really low at the moment, so we felt like we could buy anything that caught our fancy. The worst meal we had was better than the Mexican food we get at home, and that includes the ones we scarfed down at Mexico City airport. At the best restaurant in town (so we were told), Los Danzantes, we had mezcal margaritas and wine, fantastic mole entrees, and as appetizer I had one of my favorite foods, octopus – not rings of calamari, but a big slab of pulpo with ancho chile sauce. We ate and drank like there was no tomorrow, and the bill for two was $855 – that’s pesos, about 50 American dollars at today’s exchange rates. Other scrumptious meals didn’t even cost us twenty bucks. Waiters were relieved that we gringos could take it as spicy as they could dish it out.

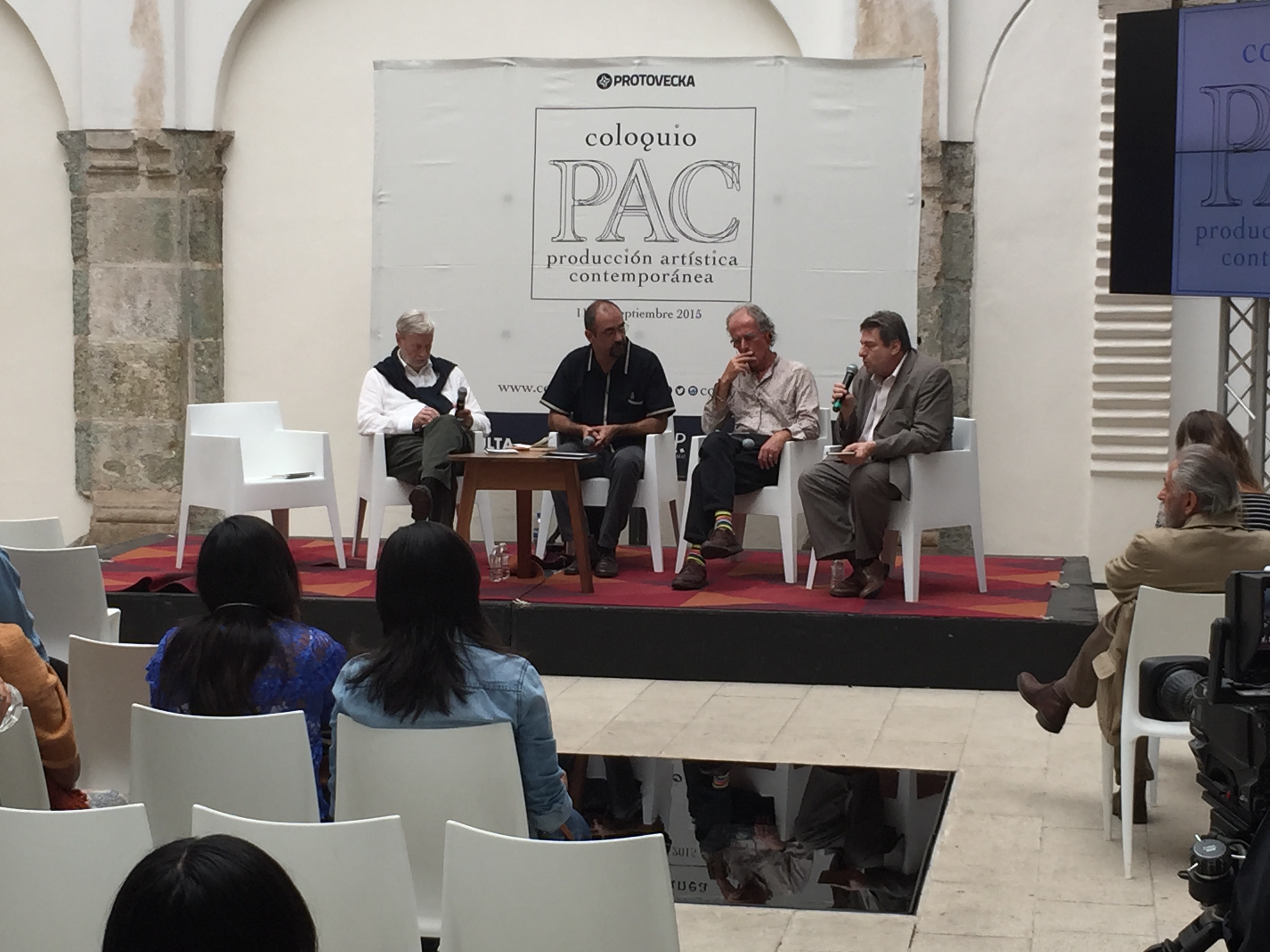

Protovecka, an arts advocacy organization run by Juan Alaya that’s only been around for a couple of years, had invited me and about a dozen other art, film, and music critics for a specifically non-academic conference trying to make connections among the arts. Protovecka and its staff reside in Mexico City, but they kindly decided that the participants would have more fun in Oaxaca. The accommodations were generous, the events well organized, and the refurbished convent in which the latter took place quite lovely. Here are Italian philosopher Gianni Vattimo, music critic and moderator José Wolffer (who knows everything about new music and with whom I had a great time), music critic and prolific author Paul Griffiths, and film critic Richard Pena, colloquy-ing on Sunday’s panel, with expert simultaneous translation for the various languages:

That foregrounded black rectangle is actually a fountain, a thin film of water over a black marble surface, creating a nicely asymmetrical open space in front of one side of the stage. In the U.S., there would have been yellow cones warning people of the danger of stepping on it, but Mexico seems more civilized than that; people are treated like adults.

It’s difficult bringing the arts together these days, and the problems were as I expected, though I applaud the effort. Film is so much part of everyone’s cultural life that the film critics get to live in the real world, even if they endlessly wish that the general public shared their rarefied tastes. The visual arts seem isolated in a self-ratifying loop in which artists, curators, critics, and rich collectors speak a language full of familiar words used in a way that the rest of us hardly comprehend. And the music critics, Paul, José, and myself, share a jaundiced view of how irrelevant (post)classical music has become to the rest of the culture. We struggled gamely to speak the same language (metaphorically) for a few days, and enjoyed each other’s company even when we failed. I was one of only two or three Americans, and it was viscerally comforting to spend a few days conversing with professionals from Mexico, France, Italy, and England, who seem free of the defeatism and pessimism that pervades the U.S. worldview these days. I left with a feeling that things will eventually be all right here, too.

And to get the really long view of cultural change, Nancy and I took a cab (24 bucks round trip) out to Monte Albà n, the mountain site of the center where Zapotec civilization flourished strangely from 500 BC to about 850 AD:

As many as 17,000 people lived in this space at some time, which took us an hour and a half to circumnavigate;Â there were underground tunnels through which priests could run from temple to temple, and an altar for human sacrifices. Certain sites were dotted with carved figures which, when originally discovered by Europeans, were referred to as “the dancers” – Los Danzantes. Turns out they seem to have been portraits of neighboring kings who were castrated and mutilated upon capture:

I guess if the Zapotecs could last here for 1350 years, we Americans can hold on for a few more centuries. Aside from maybe our minimalism conferences where I get to see all my old friends, I can’t think of a cultural event I’ve ever been invited to that I enjoyed more. Next week: Minimalists in Helsinki!

UPDATE: A couple of things. One refreshing difference between this and most of the American conferences I’ve been to lately is that there was almost no mention of critical theory. I didn’t attend every lecture, but only the name Deleuze came up, and only once. There was a lot of talk about Heidegger, whom I’ve read a lot of and took a graduate course in once, and Vattimo mentioned the aesthetician Mikel Dufrenne, whom I read a lot of in college but hadn’t heard of since. So, in terms of intellectual history, I felt rather at home. And it made me wonder if critical theory is only an American obsession.

Also, I always buy Cuban cigars in Mexico, and in every other country I visit. But in Oaxaca I didn’t see a single cigar store, or even anyone smoking a cigar, and when I asked at the front desk, the bewildered employees couldn’t think of anything, and finally located on a map a kiosk in the zocalo. Well, I wasn’t going to go search out a crummy kiosk for a cigar, so for once I came home without any. I was surprised to find that there are places in Mexico where cigars are virtually unknown.

Mole and Tequila

A few months ago, I was supposed to be in Italy this week for a totalism festival at Bari Conservatory. That got canceled or postponed due to massive administrative changes at the Conservatory, so maybe it will happen later, or not.

So instead I accepted an offer to lecture at Coloquio PAC in Oaxaca, Mexico, a symposium on contemporary artistic production. Paul Griffiths, José Wolffer, and I will be the speakers on music, and I am supposed to talk for 45 minutes about (clear throat) The State of Music – something I feel I currently know nothing about, except that the public state of music excludes just about any musical ideas I could imagine ever taking an interest in. I’ve got some Usual Things to Say and bits from my blog, and I have to leaven the whole with enough humor and optimism to not become an old man’s rant. I once saw Luciano Berio, whose music I respect and sometimes love, give an old man’s rant about how everything was going to hell, and it was not edifying. Luckily the target of my diatribe is not (and never is) Young People Today but rather the reigning corporate dictatorship which is guaranteed to warp or marginalize any honest musical impulse, and I am hardly the only writer around demonizing that particular bugbear. And if I succumb to gloom, Oaxaca is rumored to be the world center for mole and tequila, two things that could cheer me up even in the direst circumstances.

If I Had a Player Piano, I’d Be on a Roll

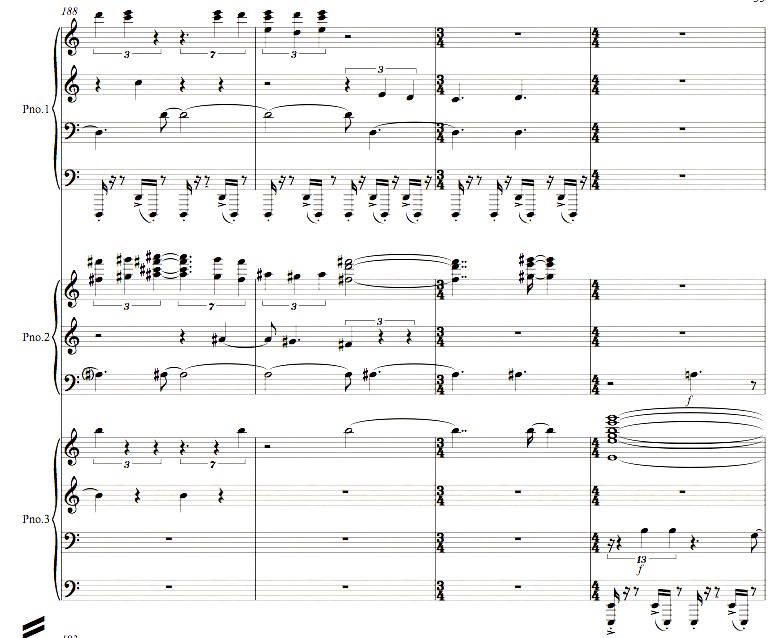

Another three-Disklavier piece in my 33-pitch 8×8 tuning:

Futility Row (2015), 8:53

It’s in the key of E-13-flat minor. That is, since my 1/1 is E-flat, the tonic here is the 65th harmonic (major third of the 13th harmonic), 27 cents sharper than E-flat. I have a penchant for minor keys, and it’s difficult to write a minor-key piece in a scale constructed from harmonic series’. I gained a new empathy for Haydn, who, in his minor-key symphonies, always seems to modulate into the major as quickly as possible. Schoenberg remarked that Chopin was lucky because, if he wanted to do something that sounded new, all he had to do was write something in F# major. Well I’m way ahead of Chopin, because not only am I the first to write something in E-13-flat minor as far as I know, I have lots of other exotic keys left to use. This is a particularly Gannian piece in form and gestural style. But I got the idea while humming a song by Mikel Rouse, and so I dedicate it to him, whose music has so often been a means of bringing me back to earth.

I’m Weird

I can now offer the recording of my Snake Dance No. 3 as performed at the Bang on a Can marathon at Mass MOCA on this past Aug. 1. The intrepid performers are David Cossin, Kaylie Melville, Colin Malloy, Wade Selkirk, percussion; Vicky Chow, Karl Larson, keyboards; and Cody Tacaks, bass. It’s a weird piece, the only time I’ve combined the wild percussion rhythms of my Snake Dances with microtonally-tuned synthesizers, in a 19-tone completely irregular scale. I limited the number of pitches so that the fretless bass player wouldn’t have to learn too crazy a scale, given the crazy, tuplet-filled rhythms involved. It is indeed a weird piece. Right after the performance one of the presenters (who might not want to be quoted by name) came up to me and said, approvingly, “That’s a really weird piece.” And several people present mentioned that it stood out on the festival as being different, and that people either loved it or hated it. Glenn Branca and Rhys Chatham not being represented, it was neat to be, for once, the wild, loud piece on Bang on a Can, since I am perfectly capable of writing the kind of tonal, pretty pieces that were otherwise prevalent. It was a really attractive festival.

The word weird grates on me a little bit, since in the signatures in my 1973 yearbook for Skyline High School in Dallas, the word weird is remarkably prominent in almost every entry. I seem to have been the weirdest guy anyone in my high school had ever met. (I was playing atonal piano music by Wolpe and Rochberg in a Texas high school in the early ’70. Some kids concluded, upon hearing me play, that I was completely incompetent.) But even by my exalted standards, this is a weird piece, the farthest out on a ledge my music has ever ventured. The 2010 world premiere by the Sam Houston University Percussion Ensemble was impeccably well played, but technically problematic, since all the synthesizers (including the fretless bass part I myself played on keyboard) were run through a single speaker, and didn’t blend with the percussion at all. I revised the piece for this performance, and I think it’s much tighter, and there will never be a better performance. But I have to admit, it’s a weird piece – perhaps the weirdest piece from an apparently pretty weird composer.