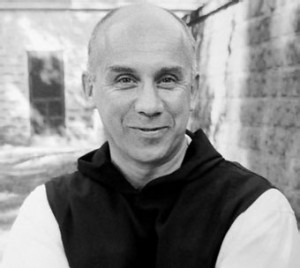

Eleven days ago my friend, colleague, and department chair James Bagwell wrote me to ask me to write a piece for the May Festival Youth Chorus in Cincinnati, which he conducts. The premiere is to take place in a Catholic basilica, and so the text needed to be suitable. Ezra Pound was not going to do the trick. But among Catholic writers I have always found Thomas Merton enormously appealing, and among his voluminous poetry output I quickly settled on In Silence, which begins thus:

Eleven days ago my friend, colleague, and department chair James Bagwell wrote me to ask me to write a piece for the May Festival Youth Chorus in Cincinnati, which he conducts. The premiere is to take place in a Catholic basilica, and so the text needed to be suitable. Ezra Pound was not going to do the trick. But among Catholic writers I have always found Thomas Merton enormously appealing, and among his voluminous poetry output I quickly settled on In Silence, which begins thus:

Be still.

Listen to the stones of the wall.

Be silent, they try

to speak yourname.

Listen

to the living walls.Who are you?

Who

are you? Whose

silence are you?Who (be quiet)

are you (as these stones

are quiet). Do not

think of what you are

still less of

what you may one day be….

It’s a wonderfully mystical poem about silence and listening, and so I used more silence within the piece itself than you’d find in any dozen recent pieces of mine. (I’m kind of a nut about continuous flow – I resisted my instincts this time). It must also be one of Merton’s best-known poems, because my wife remembered the nuns teaching it at Marywood Academy in Grand Rapids fifty years ago.

It is the centuries-old strain of Catholic mysticism that Merton represents that prevents me from becoming quite as cynical about the Christian church – horrifying as I agree it is in most contemporary manifestations – as most liberals are these days, and makes the writing of music with spiritual overtones still a possibility for me. (I had a grad student turn away from my Transcendental Sonnets with a shudder a few years ago because they mentioned God.) I encountered Merton first of all through my readings in Zen, and it was the commonality he could see underlying the original Christianity and Asian religions that gave his writing a not only palatable but attractive depth. One of my favorites of his more-than-seventy books is The Wisdom of the Desert, which is mystic sayings of the church fathers from before Christianity ever became a state (or even tolerated) religion, sort of a collection of Christian koans. In his “Letter to Pablo Antonio Cuadra” Merton wrote,

One of the tragedies of the Christian West is the fact that for all the good will of the missionaries and colonizers… they could not recognize that the races they conquered were essentially equal to themselves and in some ways superior….

If I insist on giving you my truth, and never stop to receive your truth in return, then there can be no truth between us…

Whatever India had to say to the West she was forced to remain silent. Whatever China had to say, though some of the first missionaries heard it and understood it, the message was generally ignored and irrelevant. Did anyone pay attention to the voices of the Maya and the Inca, who had deep things to say? By and large their witness was merely suppressed. [Emphasis in the original]

Merton has an almost Mark Twain-esque streak of sarcasm in his contemplation of the infinitely fallible and self-important human race, and there are other Merton poems I could imagine setting, including Sincerity, a very appropriate poem for our politically divisive times:

As for the liar, fear him less

Than one who thinks himself sincere,

Who, having deceived himself,

Can deceive you with a good conscience.One who doubts his own truth

May mistrust another less:Knowing in his own heart,

That all men are liars

He will be less outraged

When he is deceived by another…So, when the Lord speaks, we go to sleep

Or turn quickly to some more congenial business

Since, as every liar knows,

No man can bear such sincerity.