I remember Morton Feldman saying in the ’70s that if there was one musical idea that was finally dead, it was multimovement form. (Was I present when he said it? I can’t recall.) That seemed about right at the time, and, like most of the progressive composers I associated with, I pretty much wrote only one-movement works in the 20th century. But starting with Transcendental Sonnets in 2001-2, I became interested in the multiple movement problem. In recent years many of my works have divided into movements, and I’ve had to grapple with what my conception of the form is. My aesthetic is postminimalist – and by that I mean I do have my own aesthetic, and by comparison with other composers whose style it resembles, I can locate it as postminimalist, but it is simply the style I feel driven to write in, and I could just as easily call it Gannian and leave everyone else out of the picture. It is personality, not ideology; not a political strategy, but simply the route my imagination takes. The style itself produces highly unified movements of little internal contrast. (I could have adopted “No-Drama Gann” before it got applied to Obama.) My music shuns development, rarely relies on tension and release, nor am I comfortable bringing back the same main idea in one movement after another. In this sense I am not really a symphonist in the sense of most modern symphonists, as my friend Robert Carl is; my ideas do not progress from movement to movement. I have often felt that I produce suites, not sonata- or symphony-type works.

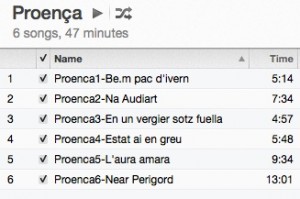

I’ve finished a draft of Proença, my song cycle on Ezra Pound. I think it’s one of the best things I’ve ever done, though one tends to think that when the ink is still wet, and especially when the piece is ambitious. Unlike my other song cycles, it is not merely a collection but a large structure, and I’ve come closer than ever to feeling what multi-movement form means for me. At 47 minutes, it’s my second longest work next to The Planets. The timings of the Sibelius files are as follows:

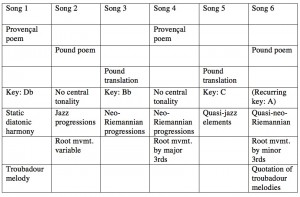

I was aware as I was composing that I was selecting poems and song idioms to balance each other off, and that the tendency of one song in one harmonic or textural or rhythmic direction seemed to imply the necessity of another song going in the opposite direction. Once the sixth song clicked into place I realized I was finished, because there were no more variables within my system with which I could create further contrast. And once I got nearly finished I made up a chart showing the kinds of symmetries I ended up with (click on images for better resolution):

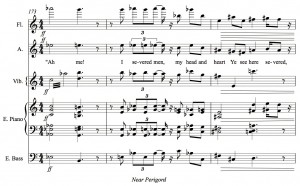

Two of the songs are original Provençal poems; two are Pound translations of Provençal poems; and two are poems Pound wrote in response to response to Bertrans de Born’s poem “Dompna puois.” In addition, the 1st, 3rd, and 5th songs are each set in a single, unchanging tonality; the 2nd, 4th, and 6th have no central key. Songs 3 and 4 are characterized by neo-Riemannian chord progressions (closely chromatic voice-leading), one in the context of a stable tonality, the other in a kind of free-floating (though consonant) atonality. Song 2 uses more of a jazz sense of progression; Song 5 has jazz elements in the harmony as well, though it doesn’t change key. In Song 4 the root movement is typically by major 3rds, in Song 6 it is mostly by minor 3rds. Actual troubadour melodies are quoted only in Songs 1 and 6, foregrounded in the former and backgrounded in the latter. Songs 1 and 3 both follow a kind of additive process, 1 and 4 both have an articulated steady pulse, 1 and 5 share a pointillistic texture. Songs 1, 3, 4, and 5 are stanzaic, and I handled stanzaic form four different ways:

Two of the songs are original Provençal poems; two are Pound translations of Provençal poems; and two are poems Pound wrote in response to response to Bertrans de Born’s poem “Dompna puois.” In addition, the 1st, 3rd, and 5th songs are each set in a single, unchanging tonality; the 2nd, 4th, and 6th have no central key. Songs 3 and 4 are characterized by neo-Riemannian chord progressions (closely chromatic voice-leading), one in the context of a stable tonality, the other in a kind of free-floating (though consonant) atonality. Song 2 uses more of a jazz sense of progression; Song 5 has jazz elements in the harmony as well, though it doesn’t change key. In Song 4 the root movement is typically by major 3rds, in Song 6 it is mostly by minor 3rds. Actual troubadour melodies are quoted only in Songs 1 and 6, foregrounded in the former and backgrounded in the latter. Songs 1 and 3 both follow a kind of additive process, 1 and 4 both have an articulated steady pulse, 1 and 5 share a pointillistic texture. Songs 1, 3, 4, and 5 are stanzaic, and I handled stanzaic form four different ways:

Song 1: Static accompaniment, three different melodies

Song 3: Melody becomes more developed with each repetition; final envoi switching to a slower tempo

Song 4: Through-composed, no repetition

Song 5: Repetition of both melody and accompaniment; final envoi switching to a homophonic texture

There are other, smaller ways in which the songs echo each other.

I planned out none of this structure in advance, but kept adding new poems as I instinctively felt gaps in the overall conception. There is no particular narrative arch to Proenca, but I think this is typical of how I tend to create variety in a multimovement piece, mixing and matching an array of qualities from movement to movement for a gradually shaded set of perspectives on similar material. The movements share family resemblances; given seven qualities, each pair of movements may share four or five of those qualities in diverse combinations. No linear energy runs from movement to movement, but each balances the others and helps complete the total picture. And while I kept changing the order of the songs, a certain logic finally dictated the order I came up with, so that too-similar songs weren’t placed too close together. (Complete program notes for the piece are here. And parenthetically, I hope someone can suggest how to get a C with a cedilla to happen in html.)

Looking back, I can see that I’ve instinctively operated this way in other multimovement works. I rarely reuse material from one movement to another (though little melodic ideas do sometimes get transposed, since I like to work on the movements simultaneously), but all the movements together do provide a series of different perspectives on not a single idea but a group of associated ideas. In short, I guess what I’m leading up to saying is that I think I’m a pretty damn good composer, I just don’t do what people expect. But who knows.