I’m snowed in, and statistically speaking, you probably are too. So let’s blog some of my Ives book, and I’ll give you my complete analysis of the Alcotts movement. I’ve already written about Ives’s mysterious references to Lizzy Alcott’s piano, and I won’t repeat that section here. At issue is which parts of the movement were meant to bring to mind Louisa May Alcott and her famous novels for children, and which her fecklessly philosophical father, Bronson Alcott. You’ll need to know a couple of things from earlier in the book to follow the analysis below. One is that the keys of E-flat and A are paired as oppositional tonalities throughout the Concord Sonata, in all four movements. The other is that Ives used a kind of source chord for the entire sonata, consisting of four, five, or six notes of a whole-tone scale along with one note from the opposing whole-tone scale. I call it the “whole-tone-plus-one” collection.

Now, one of my anonymous external readers insisted that I add some “theoretical commentary” about the whole-tone scale, what its properties are. Let that sink in a moment: the whole-tone scale is one that every college music major knows, and its properties are very simple and pretty limited. It’s all whole steps! Nevertheless, I had already written five pages about what the whole-tone scale would have meant to a musician of Ives’s generation, relating it to Helmholtz and the harmonic series, quoting Henry Cowell’s view of it, conceptualizing it in terms of Pythagorean tuning (which was an explicit interest of Ives’s), and talking about its implications for jazz chords in terms of sharp 11, flat 13, and so on. And that wasn’t enough! I was supposed to write more about it! How many of you reading this could write more than five pages about the properties of the whole-tone scale – not its use in specific pieces, but its properties? And assuming you’re already capable of reading a book of musical analysis, how much would you need of that in order to understand a whole-tone reference?

* * * * * * * * * * * * * *

…Ives’s view… that Bronson Alcott might be more kindly remembered if the dictagraph had been invented decades earlier (allowing him to record his extempore verbal flights), is an opinion with a long tradition behind and ahead of it. Ives takes Alcott’s reputation on faith, calling him “an exuberant, irrepressible visionary†with “[a]n internal grandiloquence [that] made him melodious without [p. 45].†He is more condescending to the family’s more famous daughter: “Miss Alcott is fond of working her story around so that she can better rub in a moral precept – and the moral sometimes browbeats the story [p. 46].†Though he attributes a didactic streak to both, he emphasizes their differences: “The daughter does not accept the father as a prototype – she seems to have but few of her father’s qualities ‘in female’ [p. 46].†Ives also signals his intention not to depict either individually. “We dare not attempt to follow the philosophic raptures of Bronson Alcott,†he writes,

and so we won’t try to reconcile the music sketch of the Alcotts with much besides the memory of that home under the elms—the Scotch songs and the family hymns that were sung at the end of each day—though there may be an attempt to catch something of that common sentiment… – a strength of hope that never gives way to despair – a conviction in the power of the common soul which, when all is said and done, may be as typical as any theme of Concord and its transcendentalists. [p. 48]

Elsewhere in the Memos, however, he mentions that the music tries to suggest the tales, incidents, and characteristics of the authors, and that “the Alcott piece tries to catch something of old man Alcott’s – the great talker’s – sonorous thought.â€15

All this raises a question for the listener to The Alcotts, for all of its relative simplicity. Much of the movement is gentle and idyllic, but not all of it. Two passages in particular seem rife with struggle: the dissonant, crescendoing play of the Beethoven’s Fifth motives on p. 54, and the whole-tone flavored approach to the triumphant “human faith†theme on p. 57. It is tempting, of course, to fall back on gender stereotypes and link the calm, more tonal sections to Louisa May’s children’s books, and the more agitated struggle to Bronson’s “philosophical raptures†and “sonorous thought.†But Ives throws a wrench into that argument in the Memos, where he likens the bitonal key signatures of the opening to his fantasy that “old man Alcott likes to talk in Ab, and Sam Staples likes to have his say over the fence in Bbâ€16 – Sam Staples being the Concord constable who once threw Thoreau (and, earlier, almost threw Alcott) in jail for conscientiously refusing to pay the poll tax, and a later source of anecdotes about Thoreau, Alcott, and others. (No discredit accrues to Staples, who offered to pay Thoreau’s tax himself if Thoreau would let him.17) So the gentle first page, in Ives’s mind, seems connected to Bronson Alcott’s famed serenity. In addition, the stormier second page quotes the Beethoven’s Fifth motive liberally, and Ives talks of Louisa May’s little sister Beth “playing at†Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony.

Should we, therefore, reverse gender roles here? Louisa May was after all the practical member of the family, the one who went to work, published salacious stories under a pen name, and, with Little Women and its successors, secured a comfortable old age for her feckless father and his long-suffering wife. Along with her mother, she seems to have been the fiery one in the family. Louisa May/Jo’s struggle to control her temper is one of the major themes of Little Women. Sophia Peabody, who lived for awhile with the Alcotts, adored their restful companionship, with the single exception of Louisa May: “Her force makes me retreat sometimes from an encounter,†she wrote with a shudder.18 Could the quiet opening represent Bronson’s calm talk of the spiritual immensities, and the gathering storm Louisa May’s untamable fury, or her steely determination to raise her family out of a poverty that was not always genteel? Or do we more obviously relate the domestic, parlor-song quality of the middle section to Little Women, and think of the jagged, irregular dissonances as the attempt to express the ineffable relation of Spirit to Matter? Can we do both at once? Could Ives, limited as his view of Louisa May probably was to the children’s books, have sensed her darker side, or is to think so an anachronism of our post-feminist vantage point? Ives leaves us to imagine the entire movement as an idyllic life under the elms, infused at times with “a strength of hope that never gives way to despair,†but, certainly, the music circumscribes a dichotomy more violent than this suggests.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

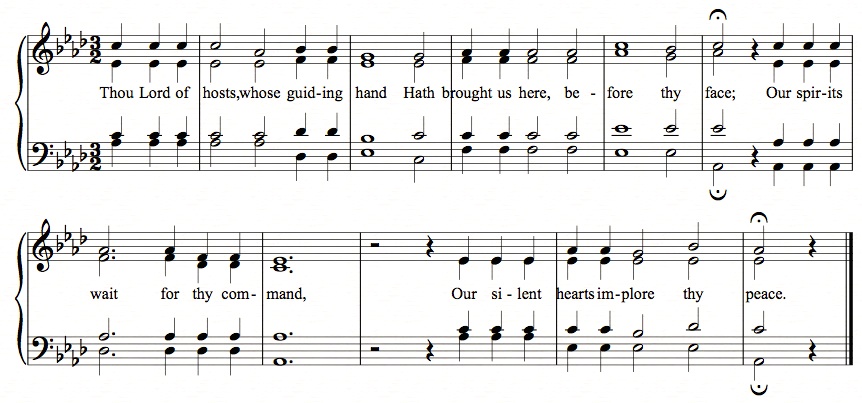

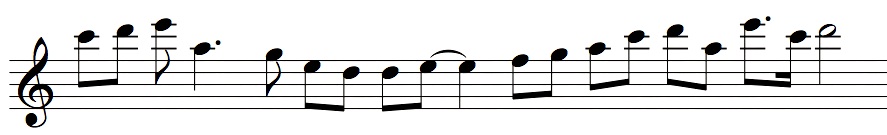

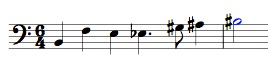

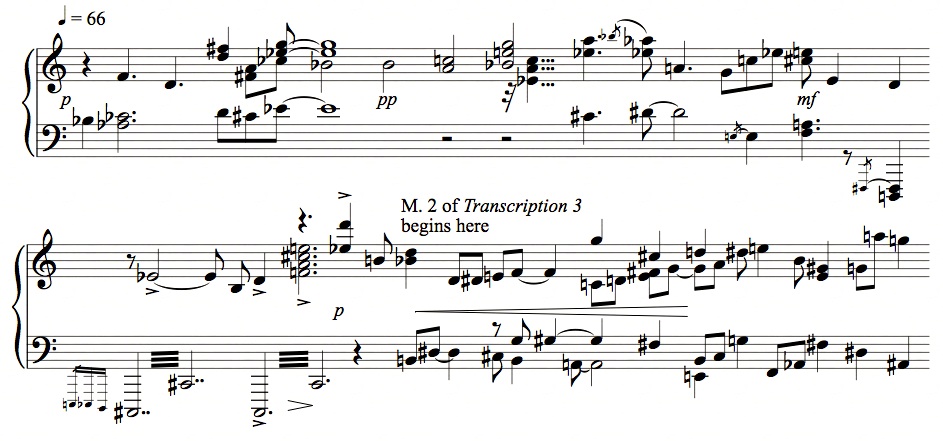

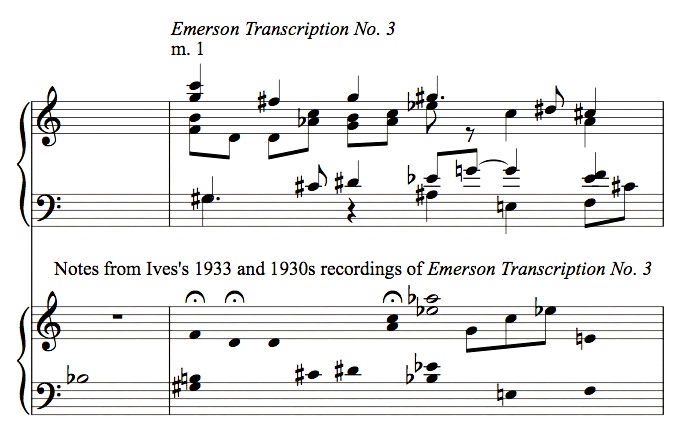

The Alcotts movement is primarily concerned with the Human Faith theme, and also with the related Missionary Chant hymn; indeed, it is only this movement that requires us to take notice of the Missionary Chant at all. Ex. 9-1 gives the music in full.

Ex. 9.1 Missionary Chant

What we want to particularly notice are the motives of a repeated note followed by a falling major third that open each half of the verse, in slightly different rhythmic configurations.

The Alcotts movement is something of a clear ABA form, and its harmonic structure is, by Ivesian standards, remarkably simple as well. Within the first A section, after two brief phrases each based on the Missionary Chant, the Human Faith theme is repeated no fewer than three times, all three of them in the key of B-flat: at syss. 53-2/3, from syss. 53-4, m. 2 to 54-1, and from syss. 55-1, beat 7, through the first measure of 55-3. All of these employ both halves of the theme, though in the first some notes are altered or omitted, and the second veers off in the middle of the second half for an extended passage of development. At the final measure of sys. 55-3 begins an unmistakable, calmer and more conventional B section in a kind of American parlor-music style, which is itself repeated. The final A section, for which we can choose sys. 56-5 as a reasonable starting point, plays around with motives from the Human Faith theme for four systems, leading to a climactic statement of the entire theme in the key of C. As we’ve noted before, this is the theme’s most complete and defining statement in the entire sonata.

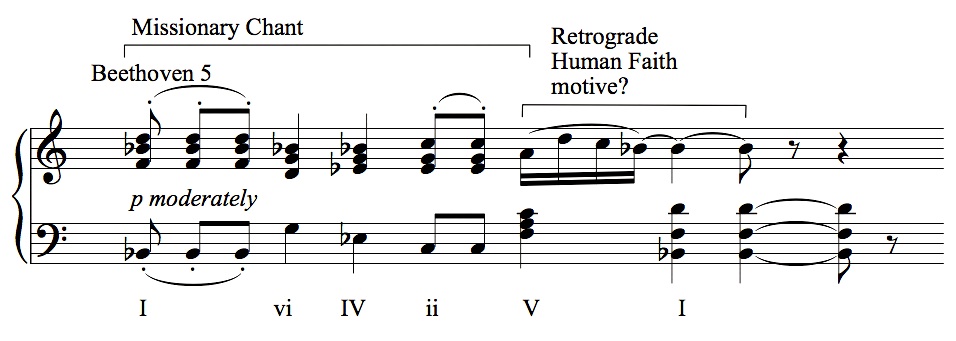

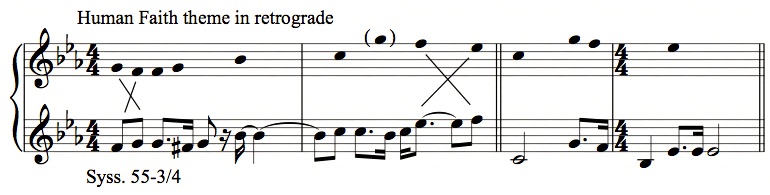

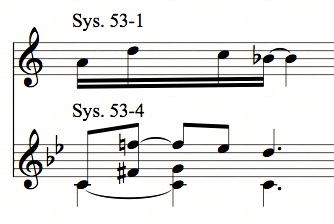

The Alcotts opens with the most conventional chord progression we’ve yet heard in the piece: I vi IV ii V I, pure and simple and logical, in the key of B-flat. The first eight notes of the melody outline the hymn Missionary Chant, except that the drop of a major third occurs between the third and fourth notes instead of the fourth and fifth – meaning that a Beethoven’s Fifth quote is included as well; in fact, Ives switches around the openings of the Missionary Chant’s two phrases, using D-D-D-Bb first and then D-D-D-D-Bb, instead of the other way around. And the odd little melodic flourish at the end of the phrase seems to be a Human Faith motive in retrograde, with the perfect fifth replaced by a perfect fourth (Ex. 9.2).

Ex. 9.2 Sys. 53-1, first half

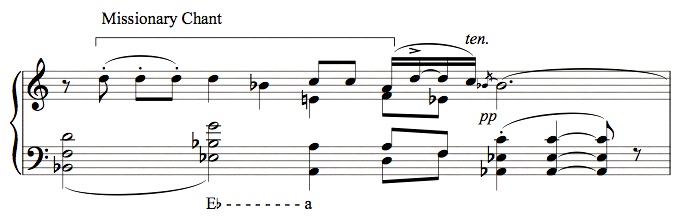

The phrase repeats, and this time the melody follows the opening of the Missionary Chant rather than Beethoven’s Fifth. The harmony, however, goes to the subdominant, Eb, rather than the vi chord, which is natural enough; but then the Eb is followed by a chord that doesn’t fit in Bb major at all, A minor (Ex. 9.3).

Ex. 9.3 Sys. 53-1, second half

And so, as the Missionary Chant flows blissfully overhead, Ives has reintroduced our Eb-A opposition. The root movement goes a tritone from Eb to A, a logical fourth from A to D, up to the dominant of Bb, only to land unexpectedly on Ab major, a whole-step below our implied Bb cadence. Ives has packed a lot of meaning into the eighteen beats of this seemingly simple first line, and he is soon going to unpack it.

As mentioned in Chapter 6, we have a recording of Ives playing The Alcotts in its entirety from April 24, 1943, and we learn from it several things about his playing. One is that his hands weren’t unusually large. I have fairly large hands myself, but I can’t play that open bass triad Ab-Eb-C with my left hand without having to roll it, making the major tenth from a black key to a white; Ives couldn’t either. When he can’t split the notes between both hands, he rolls that chord. Nor does Ives always follow his own notation; in the example above, where the two D’s are tied together in the melody, Ives doesn’t play them tied, but reiterates the D over the F dominant chord.

At this point the music does something fairly radical for its time, notationally, at least. For the first time in the sonata a key signature appears, and in fact, two appear at once: Bb (two flats) in the treble staff and Ab (four flats) in the bass staff. The Human Faith theme now appears in B-flat. As mentioned before, Ives referred to this passage as Bronson Alcott talking in Ab, Sam Staples in Bb; it is curious that, of the two, the town sheriff has the Human Faith theme while the philosopher merely strums his Ab-major triads. A manuscript (f3979) shows that Ives had initially written the entire theme within the treble clef over the Ab chords, but he later took it up an octave. The theme is also incomplete; a phrase is partly missing, though Ives supplied some of the notes in a lower octave (Ex. 9.4).

Ex. 9.4 Comparison of sys. 53-2 with the Human Faith theme

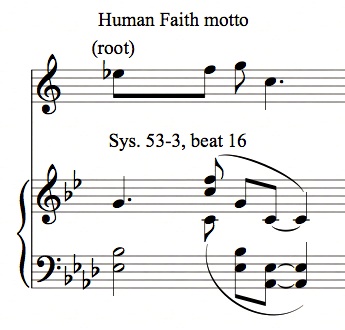

We also notice how colored this page is by the interval of a major ninth. There are several major ninths in this passage with either an internal perfect fourth, tritone, or perfect fifth added from the upper or lower note, and in sys. 53-3 the music pauses for a pair of “shadow†chords outside the key: A-F#-B and F#-E-G#. The next phrase seems to be an altered Human Faith motto altered by an octave displacement on the F (Ex. 9.5),

Ex. 9.5 Human Faith motto embedded in sys. 53-3

Ex. 9.5 Human Faith motto embedded in sys. 53-3

and its successor is a similar motto in retrograde, patterned after the ones in the first system (Ex. 9.6).

Ex. 9.6 Retrograde Human Faith motto at sys. 53-4

Ex. 9.6 Retrograde Human Faith motto at sys. 53-4

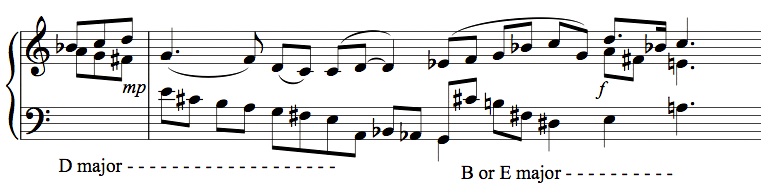

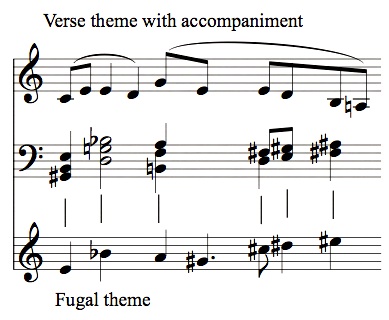

Whether we are switching from Louisa May to Bronson or vice versa, the atmosphere now changes sharply. In the middle of sys. 53-4 the Human Faith theme in B-flat then starts up again, this time with a left-hand line that accompanies it bitonally through several keys, first D major, then B major (or E major if you count the A-natural), ending up on our afore-mentioned A minor (Ex. 9.7 – in the next few examples I will be rewriting Ives’s accidentals and sometimes durations to make the musical logic clearer, so I refer the reader to the original score for a more authentic reading).

Ex. 9.7 Syss. 53-4 to 54-1

Following the progression from the first half of Human Faith to the second, this leads to a rather startlingly naked Beethoven’s Fifth motive, D-D-D-Bb. Instead of leading to the alleged Hammerklavier quotation, though, its consequent is a motive on the Missionary Chant, with the fourth and fifth notes quickened into 8th-notes (Ex. 9.8).

Ex. 9.8 Sys. 54-1, combining Beethoven’s Fifth motive and Missionary Chant contour

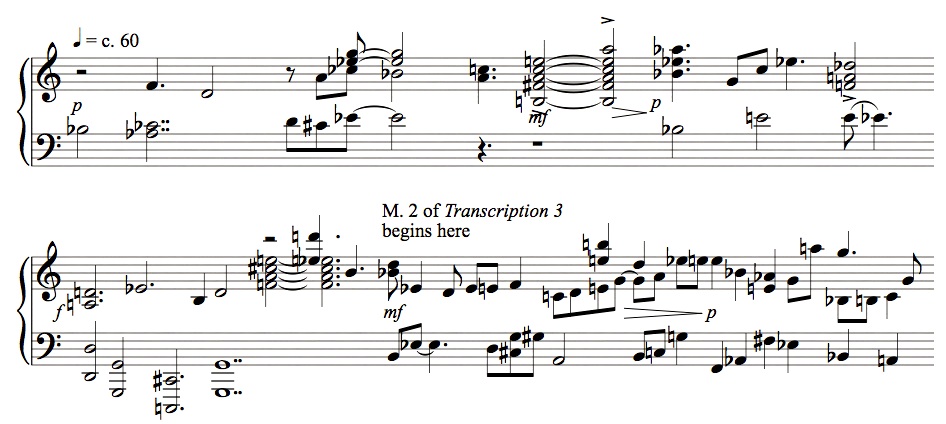

This form of what we will now call the Missionary Chant motive becomes the basis of the development that leads us away from the second half of our Human Faith theme.

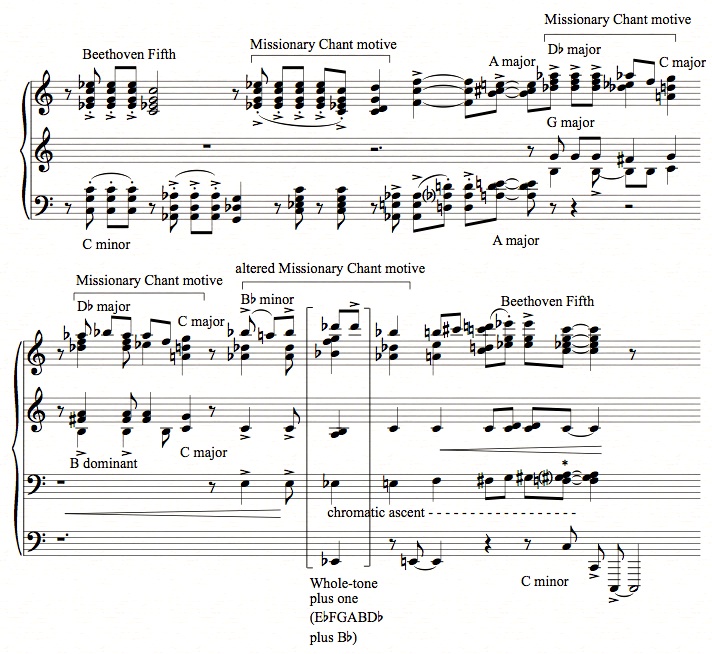

This next section is a sharp departure from the serenity of the movement so far towards anxiety and irregularity. The first Missionary Chant motive is followed by another Beethoven’s Fifth motive pounded in the Beethovenian key of C minor, which at first appears as a ii chord in this B-flat context, and then another Missionary Chant motive in the same key. This next increasingly tense passage will also end in C minor, so that what comes in-between serves functionally as what Schenkerians might call a prolongation, but a bitonal one. We see the bass echo the beginning of the movement by leading from Ab up a tritone to D, and then up a fifth to A, where we hit a chord that unexpectedly suggests A major (Ex. 9.9: once again, I alter many of Ives’s enharmonic spellings for clarity).

Ex. 9.9 Syss. 54-1/3

The subsequent Missionary Chant motive seems to outline Db major resolving to something like C major in the right hand, as the left hand plays pitches from G major, also moving to C. The next Missionary Chant motive resumes bitonality, with the upper chord rooted on C#/Db and the lower one on B, almost as though the C minor were going out of focus and blurring a half-step in both directions. The final Missionary Chant motive, altered in contour, again suggests tonalities a whole-step apart, Bb above C, and leading to a chord, the momentary climax of this progression, which contains an entire whole-tone scale plus one other note – Eb-F-G-A-B-Db and Bb – our “nature†chord from Emerson. (The chords on either side, E-C-Ab-Db-Bb, are subsets of this chord as well.) From here, the voice-leading moves chromatically upward to another Beethoven’s Fifth motive, and we find ourselves back in unassailable C minor.

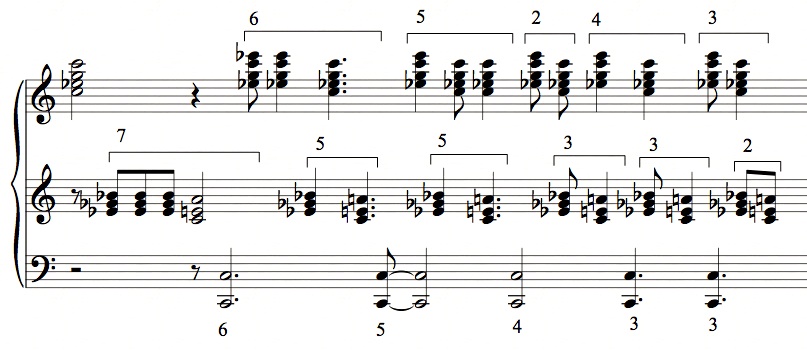

Two more statements of the Beethoven’s Fifth motive are marked by an “overtone†note, a high D dissonant with the main chord (although in his 1943 recording Ives clearly plays consonant G’s both times); such notes will recur as a feature of the movement. The subsequent dissolution of this motive is one of the most theoretically revealing passages in the entire sonata. System 54-4 is remarkable for containing only seven pitches grouped in three triads: C minor in the treble and bass and an alternation between A minor and Eb minor in the middle register (Ex. 9.10).

Of course, these triads separated by minor thirds render seven pitches of an octatonic scale – Eb E Gb G A Bb C – and the inner chords are our familiar Eb/A opposition, now contained within a firm C minor, the clearest possible statement of one part of Ives’s overall harmonic conception. Even more remarkable is how Ives, limiting himself to just these three chords and with a new attack on every single 8th-note, manages a stirring rhythmic acceleration by progressively shortening the repetition patterns. The C’s in the bass grow shorter in duration in an 8th-note pattern of 6-5-4-3-3, and the pairings of A and Eb decrease as 7-5-5-3-3-2, with the treble C-minor chords accelerating and then slowing down again, a quite audible effect. The underlying logic also makes the passage easy to memorize, even if the pianist isn’t consciously aware of it.

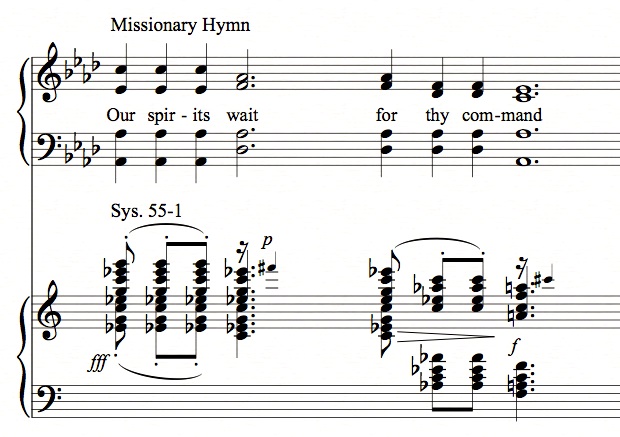

The explosion to which this process leads is full of resonance for the Missionary Chant. This time, though, it is not the hymn’s first phrase, but its third that is referred to almost subliminally, not only in its rhythm but its dropping down by thirds (Ex. 9.11), which Ives cleverly augments by one last third (G-Eb-C-A-natural) where the hymn ends with only a major second (C-Ab-F-Eb).

Ex. 9.11 Comparison of Missionary Chant with sys. 55-1

The figure pulls us back into the key of B-flat by a relatively conventional, if colorful, harmonic progression (i-VI-V/VII in the key of C, the V/VII pivoting to V of Bb), retroactively reinterpreting the C minor once again as ii of B-flat. The example is significant for illustrating the way Ives sometimes (especially in his songs, but also abundantly elsewhere) refers to musical materials that are outside the work and only incompletely instantiated within it. One need not know the Missionary Chant to understand The Alcotts: the movement makes musical sense without it. But if the opening variations on the hymn’s falling major third do bring it to mind, this veiled allusion to the complete third phrase acts as almost unconscious confirmation that the tune is in Ives’s mind, even if the music never presents the hymn in toto. On some level the music’s meaning finds completion in music that exists external to the sonata, shared in Ives’s and the listener’s memory.

The Human Faith theme makes a grand appearance next, but a recessive one, dimenuendoing away from a climax rather than building toward one. The harmonization is fairly standard, by Ivesian criteria, but it is worth noting some lovely internal imitative counterpoint, such as this unusual imitation at the lower seventh (Ex. 9.12),

Ex. 9.12 Imitation at sys. 55-1

and also a great deal of textural originality, along with some downward chromatic voice-leading that makes the huge, ripped chords seem to melt (Ex. 9.13).

The second half of Human Faith takes place more quietly in virtual 5/8 meter. The theme in the right hand is in standard B-flat major; this is rendered mysterious by the left hand, which is entirely in a whole-tone scale plus an added C# – in other words, another appearance of our whole-tone-plus-one source pitch set (Ex. 9.14).

And the section closes on an expectant Bb dominant seventh with a quiet F# echoing above. We quoted this recurring chord in chapter 3 as a highlighted example of a whole-tone chord plus a perfect fifth.

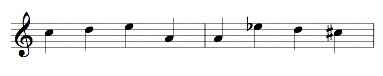

The B section that begins at the second measure of sys. 55-3 is pure parlor song material, though with the occasional ironic chromatic Ivesianism. This is clearly what Ives refers to as Beth playing the Scottish folk songs – the tune even includes an instance of the so-called “Scotch snap,†an accented 16th-note followed by a dotted 8th. The key is Eb, the subdominant of the movement’s prevailing Bb, a relationship typical of 19th-century classical ABA forms in general and 19th-century sentimental songs alike. Like so many celtic folk songs, the tune is in a kind of gapped pentatonic scale, Eb-F-G-Bb-C, with many motives of a second followed by a third in the same direction, or vice versa. This is true of the Human Faith theme as well, and in fact, in their entirety the two themes share the same pitch set, a diatonic scale missing the leading tone. Since the Human Faith theme starts high and comes downward, and the B theme here does the opposite, it seems possible (in the manner of so many classical composers) that Ives derived the new theme from some form of the old one, in this case the retrograde (Ex. 9.15).

Ex. 9.15 Middle section theme compared to Human Faith theme retrograde

To assert this abstract relationship, though, seems hardly necessary; the new melody fits programmatically and is closely related to Human Faith in intervallic style. Why the theme ends with an unmistakable evocation of the famous-to-the-point-of-hackneyed wedding march from Lohengrin presents a small mystery, though perhaps Ives was simply making a reference to comfortable domesticity, or to the fact that every 19th-century sentimental novel culminates in a wedding.

What’s more interesting is the way Ives’s own 1943 performance of The Alcotts deviates from the notation. Both times the end of this phrase comes up, in the 6/4 measure where he appends the direction “hold back a little,†Ives himself doesn’t hold back at all, but, as Ex. 9.16 shows, rather doubles the tempo of the fourth and fifth beats.

Ex. 9.16 Comparison of Ives 1943 recording to sys. 55-4

Ex. 9.16 Comparison of Ives 1943 recording to sys. 55-4

It seems to me the pianist, if he or she so chooses, is fully justified in choosing the second option, which Ives voted for with his hands in 1943, even if he voted another way with the notes in 1920 and 1947.

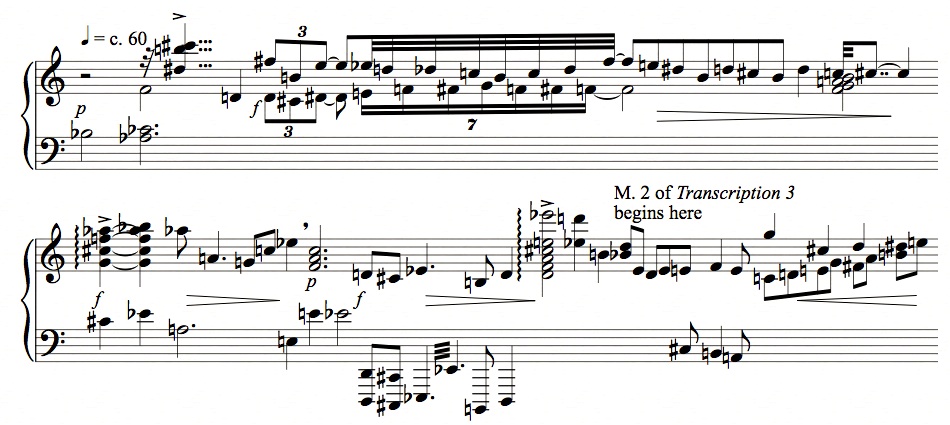

The B phrase of this little internal ABAB form is in the dominant of the B section, Bb. Musicologist H. Wiley Hitchcock has noted that the first six beats are identical to the first measure and a half of an old minstrel song, published in 1847, variously called “Stop Dat Knocking†or “Stop that Knocking at My Door†(Ex. 9.17), by Anthony F. Winnemore, who led a minstrel group called the Band of Virginia Serenaders.27

Ex. 9.17 “Stop Dat Knocking at My Doorâ€

Ex. 9.17 “Stop Dat Knocking at My Doorâ€

This italianate melody is itself a parody of Italian opera style28, and similar phrases abound in the classical literature. More essentially, its motive of a lower neighbor note leading to a rising scale becomes the generative germ of the lead-in to the final A section, recurring from syss. 56-4 to 57-3.

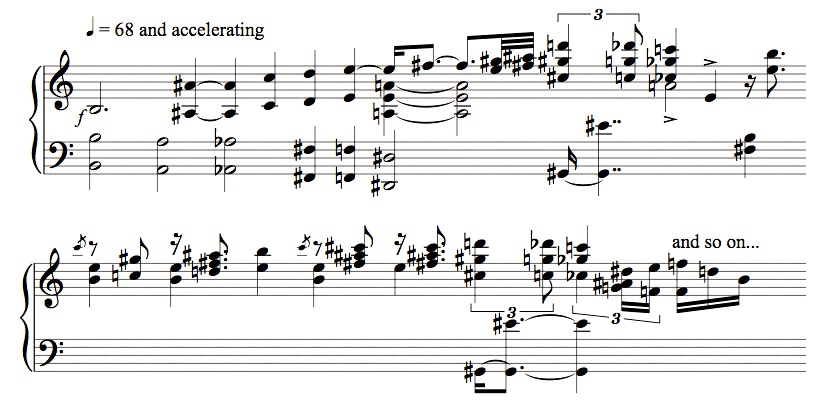

At the upbeat to m. 3 in sys. 56-4 the rising scale motive runs into a Human Faith motto, and Ives begins reintroducing dissonances. I have referred to The Alcotts, as everyone does, as an ABA form, but what Ives does here is more nuanced and complex than that implies. At sys. 56-5 the music cadences momentarily on a Bb triad, which can conveniently be taken as the beginning of the second A section. But actually, the Human Faith motto is hinted at before this (sys. 56-4, mm. 2-3), as the B-section melody continues being referred to after it. The first section A and section B are clearly articulated from each other, but the B blurs back into the second A via an interestingly gradual process, and the stage-by-stage progression back to the full Human Faith melody is in Ives’s best cumulative form manner.

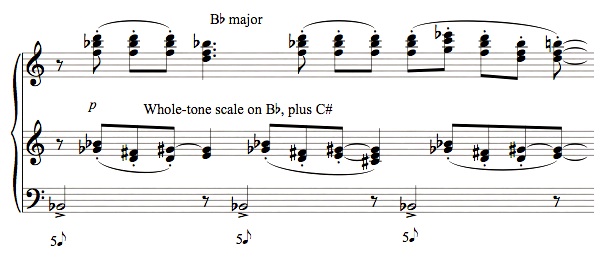

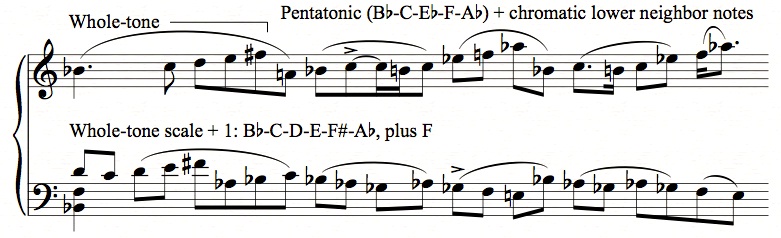

In the right hand of sys. 56-5 Ives continues the B-section material with a pentatonic scale graced with chromatic lower neighbor notes (and a final Scotch snap); the left hand begins wandering up and down a whole-tone scale on Bb with an F added (Ex. 9.18).

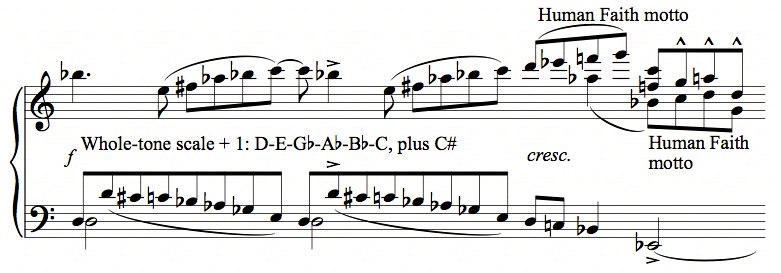

In the next system all of the notes, up until the “human faith†motto in Eb at the end, are within a whole-tone scale on D with a C# added (Ex. 9.19).

If any doubt remained that Ives was thinking of a pitch set containing a whole-tone scale plus one additional pitch, it is surely dispelled here.

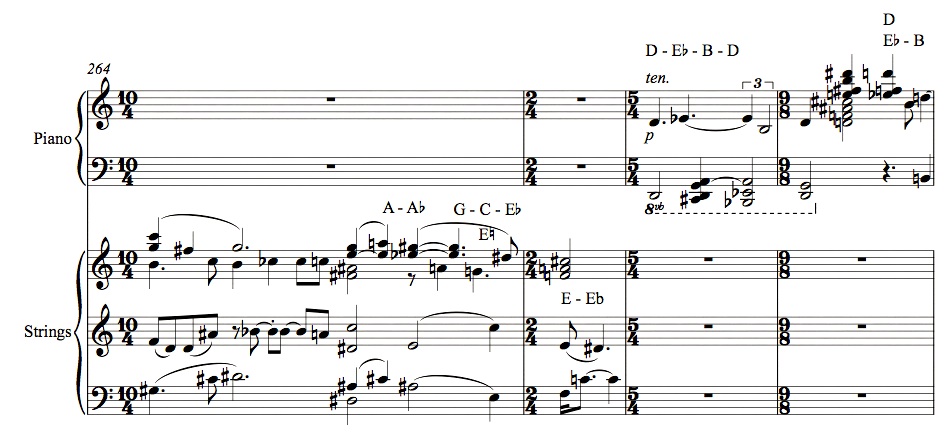

In syss. 57-2 and the first half of 57-3 the music is grounded on an Eb drone, as the left hand wanders around a whole-tone scale on D, and the right hand plays with the Human Faith motto in what could be taken as an incomplete octatonic scale: Eb-(E)-F#-G-A-Bb-C-(Db). In the middle of sys. 57-3 this relatively lengthy dominant preparation on Eb bursts into an A major triad, giving us one last taste of our Eb/A opposition. The music shifts uneasily between A-major and Bb-major triads, as the do-re-mi motives above create an elegant logic for the shift away from Bb, twice playing G-A-B, Bb-C-D, and then continuing G-A-B-C-D-E (Ex. 9.20).

Ex. 9.20 Sys. 57-3, right hand

Ex. 9.20 Sys. 57-3, right hand

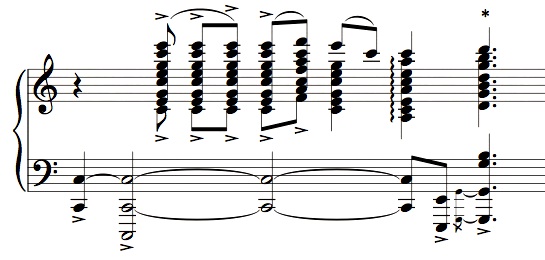

as the sonata finally bursts into its grandest statement of the Human Faith theme in its entirety, in bold, exuberant C major. The number of notes per chord, the simultaneous bass line, tenor chords, and treble melody with internal clusters and added grace notes, create a feeling that the music is trying to transcend the keyboard, bursting the bounds of what the piano is capable of. The failure of the instrument and the fingers to do justice to the emotion is almost palpable, rendering the emotion all the more affecting. Significantly, when Henry Brant orchestrated this part of the Concord (in A Concord Symphony, which will be discussed in Chapter 14), he wisely played down this passage and made it softer (marked f molto cantabile), for what sounds heroic on the keyboard would have produced only bombast in the orchestra.

Though it looks simpler than some of the others, one chord, marked with an asterisk in Ex. 9.21, has always struck me as problematic.

The upper nine notes that follow the grace-note octave in the bass cannot be played all at once by two hands of reasonable size. If Ives seriously wanted all those notes, the chord must be rolled, like its predecessor; and in fact, it is marked with a wavy roll line all the way up in the 1920 score, which he omitted in 1947. Is the top note supposed to be struck with the left hand, as so often in Ives’s gargantuan chords? This is not how he plays it in 1943; there is some rolling, but the top several notes are simultaneous with their chords. The temptation to leave out either the bottom G or the middle B is very great, but one tries to be faithful to the score, knowing that with Ives one must frequently finesse the rhythm and texture to get all the notes in. [Of the 42 recordings I own, 24 roll that chord; the rest presumably either omit a note or have very large hands.]

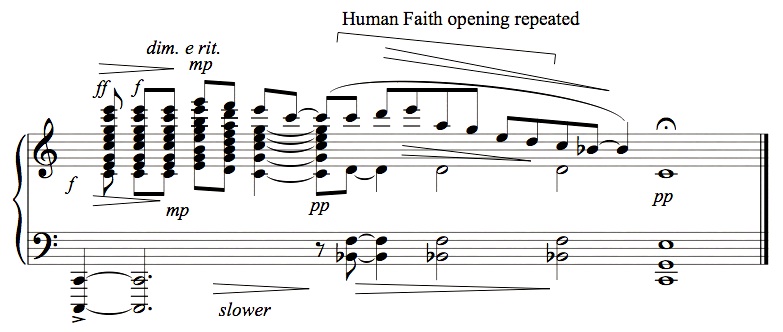

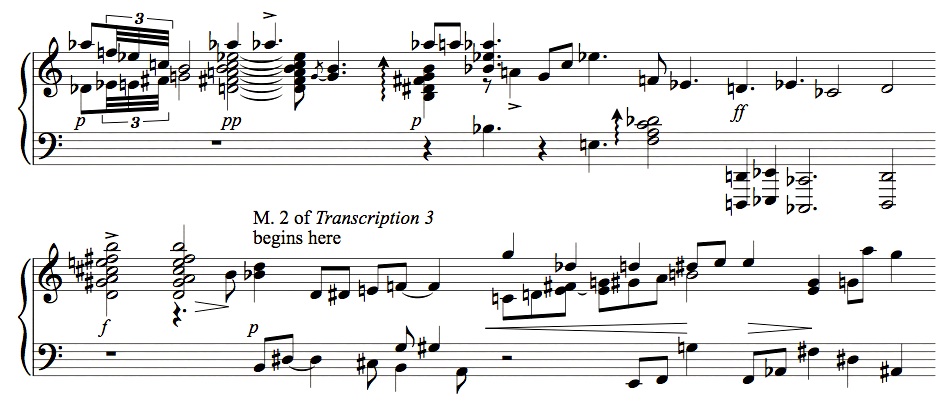

One essential feature of the Human Faith theme is that is doesn’t quite end – every single statement of it in the sonata, except this one, is a kind of a question disappearing into the ether. In this one case, though, Ives comes up with a true ending, and his solution is brilliant. He resumes the theme with a recap of its first seven notes but continuing down the scale to a Bb, over a left-hand harmony that has suddenly dropped down from C to Bb, just as in the beginning of the movement the harmony drops from Bb to Ab. For someone who is so often chary of dynamic markings, Ives throws in a humorous surfeit of them here, just where a sensitive performer least needs them as a guide (Ex. 9.22).

Ex. 9.22 Ending of the Human Faith theme in The Alcotts

As mentioned in chapter 3, the music feints towards Bb for a moment and seems about to end there, where it began, but then resolves, with a minor-seventh drop in the melody, onto one of the most comforting, reassuring, even heart-breaking C-major triads in the history of music. Oddly enough, and flagrantly contradicting his “slower†indication, Ives in his 1943 recording speeds up for this little coda, as though too reticent to draw from it all the pathos of which it is capable.

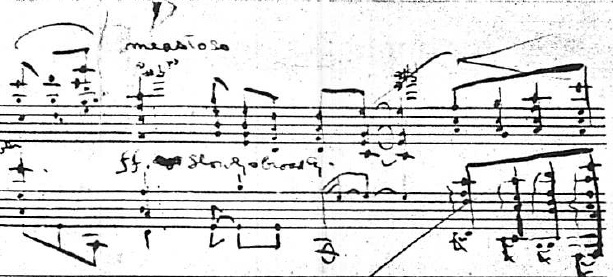

A side note: in a manuscript of the Alcotts movement (f3986 to f3991), all of the little “overtone†notes through the entire movement that ring dissonantly in the top register are F#’s except for the two high D’s in sys. 54-3. Ives toyed with the idea of inserting six such pianissimo F#’s during the final “human faith†statement. Ex. 9.23 shows a sketch from f3991, in which one can see a high F# marked pp just after a 16th-note rest above the fourth chord, and another one, crossed out, following the last chord of the phrase.

Ex. 9.23 F# overtones in f3991

There is even one above the movement’s final chord, marked ppp. Except for perhaps this last, which I rather like, Ives was right to ultimately decide against these; they would have been a quirky distraction from the grand statement he makes here. But that he considered inserting them (and they also are reinserted into a revision on the 1920 score at f4142) says something about his large-scale sense of harmony, and confirms a vague impression I sometimes get that F# is a special pitch in the Concord, saved primarily for the long statement of Martyn in Hawthorne, and otherwise rarely emphasized structurally but sometimes hovering in the background.

[15] Ives, Memos, p. 191.

[16] Ives, Memos, p. 191.

[17] Edward Emerson, Henry Thoreau as Remembered by a Young Friend, p. 64.

[18] Sophia Peabody to Mrs. William Russell, July 25, 1836; quoted in Bedell, The Alcotts: Biography of a Family, p. 125.

………

[27] H. Wiley Hitchcock, Music in the United States: A Historical Introduction, p. 167. Gayle Sherwood Magee speculates that the use of “Stop Dat Knocking†might be in ironic response to the “Fate knocking at the door†of the Beethoven’s Fifth motive; certainly a wry joke on Ives’s part if true. See Magee, Charles Ives Reconsidered, p. 135.

[28] Robert B. Winans, liner notes to The Early Minstrel Show, New World Records 80338.