Even beyond Ives, I’m on a roll lately of research on dead American composers (DACs – I wish there were more public interest in LACs, but they are a needy and competitive bunch, and I’ve discovered the pleasures of communing musicologically with the serene and undemanding dead). Aside from Robert Palmer and Johanna Beyer (of whom possibly more soon), I’ve gotten an opportunity to study Marc Blitzstein, whom I’ve always admired for his politics and for the musico-political miracle of The Cradle Will Rock. For years after I’d read about the piece I could find no way to hear it, until I got hold of the 1985 recording produced by The Acting Company. Well, my wife Nancy is general manager of The Acting Company now, which was founded in 1972 by John Houseman and Margot Harley; Houseman was the original producer of Cradle in 1937. And the company is presenting a one-night benefit revival of their 1983 production of Cradle headed by Patti Lupone, with the original cast, May 19 at the Bernard B. Jacobs Theatre, which I’m thrilled that I will get to see.

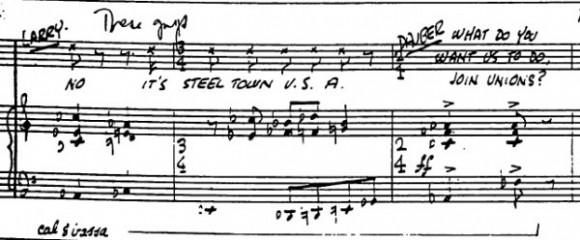

The real buzz, which got me started on this, is that as a result I got to go to the office and spend time with what is apparently Houseman’s copy of the score, which The Acting Company has in their files, and which he used to direct the 1983 performance – and may have used for the 1937 premiere as well:  Since 1999 there’s a new, engraved version, but for decades everyone relied on an old score, part hand-written and part printed, using several songs that Blitzstein published separately. There is lots of scrawled evidence of changes made in rehearsal, and comical marginal commentary. I’ve always loved Cradle and wanted to get better acquainted with the music, but since you had to rent the score for a performance to get it, never had the chance. Looking through it, I’m super impressed with Blitzstein’s composing technique: he was at the same time a determined populist and determined modernist as well (somewhat like myself), and while I knew the tunes, I was unaware how smoothly he integrated feisty modernisms into the accompaniment. Look at this opening, sung by Moll the prostitute:

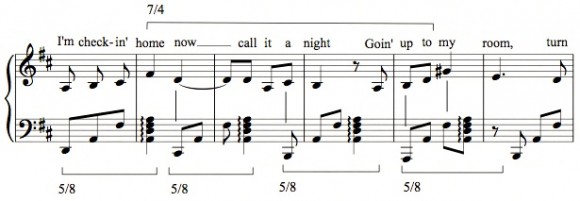

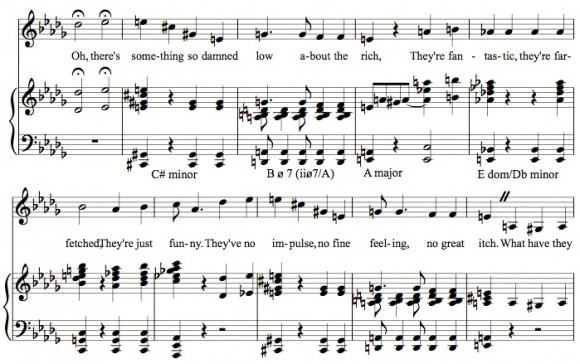

Since 1999 there’s a new, engraved version, but for decades everyone relied on an old score, part hand-written and part printed, using several songs that Blitzstein published separately. There is lots of scrawled evidence of changes made in rehearsal, and comical marginal commentary. I’ve always loved Cradle and wanted to get better acquainted with the music, but since you had to rent the score for a performance to get it, never had the chance. Looking through it, I’m super impressed with Blitzstein’s composing technique: he was at the same time a determined populist and determined modernist as well (somewhat like myself), and while I knew the tunes, I was unaware how smoothly he integrated feisty modernisms into the accompaniment. Look at this opening, sung by Moll the prostitute:  From the get-go the left-hand accompaniment runs a 5/8 accompaniment across the 2/4 meter, and the bass note always seems a second away from the melody, as though the left hand is playing a different piece, but it’s so smooth that I’d hardly noticed the discrepancies. Plus the melody itself is in 7-beat phrases, for a 14-against-5 polyrhythm so normal-sounding that I’d never noticed anything odd about it. Although the songs are catchy, I’ve always found the melodies difficult to recreate exactly from memory, and now I can see why. Blitzstein’s song-form logic is solid in an unexpected, original way, and once I play through the piano accompaniments, the harmony makes such quirky sense that the song sticks in my head instantly. Probably my favorite scene is the one in which Sasha the violinist and Dauber the painter vie for the attentions of Mrs. Mister, the town millionaire’s socialite wife and premiere arts patron. Their song “There’s Something So Damn Low About the Rich,” on a text dear to my heart,  is in D-flat, but goes from C# minor through A minor to A major, and then uses the leading tone of A as V of D-flat again. Then, having gone to A major a second time, it moves up the scale chromatically to E-flat, which becomes V/V back to D-flat with exquisite comedy:

From the get-go the left-hand accompaniment runs a 5/8 accompaniment across the 2/4 meter, and the bass note always seems a second away from the melody, as though the left hand is playing a different piece, but it’s so smooth that I’d hardly noticed the discrepancies. Plus the melody itself is in 7-beat phrases, for a 14-against-5 polyrhythm so normal-sounding that I’d never noticed anything odd about it. Although the songs are catchy, I’ve always found the melodies difficult to recreate exactly from memory, and now I can see why. Blitzstein’s song-form logic is solid in an unexpected, original way, and once I play through the piano accompaniments, the harmony makes such quirky sense that the song sticks in my head instantly. Probably my favorite scene is the one in which Sasha the violinist and Dauber the painter vie for the attentions of Mrs. Mister, the town millionaire’s socialite wife and premiere arts patron. Their song “There’s Something So Damn Low About the Rich,” on a text dear to my heart,  is in D-flat, but goes from C# minor through A minor to A major, and then uses the leading tone of A as V of D-flat again. Then, having gone to A major a second time, it moves up the scale chromatically to E-flat, which becomes V/V back to D-flat with exquisite comedy:

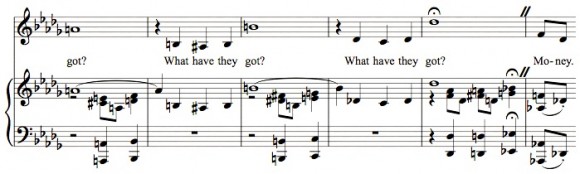

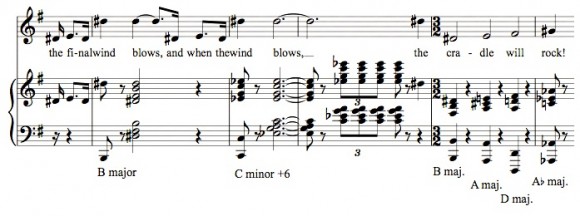

And of course there’s the title song, which is an incredibly harmonically complex song for a political musical aimed at the proletariat. I had never been able to quite get, by ear, the fairly bizarre final chord sequence:

And of course there’s the title song, which is an incredibly harmonically complex song for a political musical aimed at the proletariat. I had never been able to quite get, by ear, the fairly bizarre final chord sequence:  To shift from B major to C minor at the climax, and then end on a tritone root movement, strikes me as daringly adventurous for a 1937 musical, and probably for a more recent one as well (though I don’t keep up with recent musicals); and yet the melody is not hard to sing. Blitzstein was apparently the only composer to study with both Boulanger and Schoenberg; he preferred the former. I’m reading Eric Gordon’s biography of him, and now that I’m up to the Airborne Symphony period, I’m curious to see what form his slide from international fame into relative obscurity took. I’ve always admired him politically, and I’m glad to learn that he can be admired for the originality and personality of his compositional technique as well.

To shift from B major to C minor at the climax, and then end on a tritone root movement, strikes me as daringly adventurous for a 1937 musical, and probably for a more recent one as well (though I don’t keep up with recent musicals); and yet the melody is not hard to sing. Blitzstein was apparently the only composer to study with both Boulanger and Schoenberg; he preferred the former. I’m reading Eric Gordon’s biography of him, and now that I’m up to the Airborne Symphony period, I’m curious to see what form his slide from international fame into relative obscurity took. I’ve always admired him politically, and I’m glad to learn that he can be admired for the originality and personality of his compositional technique as well.