I have been able to locate, on the internet, 33 35 38 [see update below] commercially available recordings of the Concord Sonata (well, actually only 32 37, since one of those is Jim Tenney’s recording, which one can hear on Other Minds, but which isn’t for sale). Of those 33 38, I possess 19 24, and two one more (the John Jensen and the Roberto Szidon, which latter I think I used to have on vinyl but can’t find) are on their way in the mail. I am going to disappoint readers of my book, and probably of this blog as well, by refusing to name my favorite. There are several reasons for this. One is that that’s a music critic’s job, and I’m no longer a critic; I’m interested in the sonata, as sketched and printed, not in its various instantiations. Another is that I just don’t plan to get familiar enough with all of them to be able to recognize in a blindfold test which is which. And the most important is that I’m not a good enough pianist to register a really well-informed comparison opinion in a book as scholarly as I mean this one to be. In matters of touch, tone color, inner voices, and so on, I’m just not that impressed with the authority of my own opinion. If it’s some consolation, I’m currently tremendously wowed by Marc-André Hamelin’s second recording of 2004. And John Kirkpatrick’s classic second recording of 1968 is so firmly embedded in my ears that I tend to compare all the others to it.

But I am interested in the statistics and performance tradition, and I think it’s worth knowing which pianists used which available variants. The most important feature is whether the optional flute is used at the end of Thoreau. I consider it not optional at all, really, but crucial. For one thing, there’s an early, pre-1914 manuscript of a passage for flute and piano using an early version of the “Human Faith” theme – when it had not yet acquired the E-E-E-C Beethoven’s Fifth motive – which I think strongly suggests that that theme was originally conceived for Thoreau (Henry David Thoreau loved to play the flute while boating on Walden Pond), and that it was, in fact, the generating idea of the entire sonata. Also, Ives equivocated on what the piano should play when the flute is absent, and in all versions left the melody at this point distressingly incomplete. Thus I have come to find the versions without flute distinctly unsatisfying.

More problematic is the questionable appearance of the brief viola solo called for at the end of Emerson. It seems to be a holdover from the Emerson Concerto from which the Emerson movement eventually evolved, and while I have seen some emphatic comments that the viola definitely wasn’t intended to be played by an extra soloist, I can make a reluctant case from the manuscripts that Ives did indeed call for it. In live performance I think it would be more distracting than it’s worth, but on recording it can have a certain charm. I certainly have no objection to omitting it.

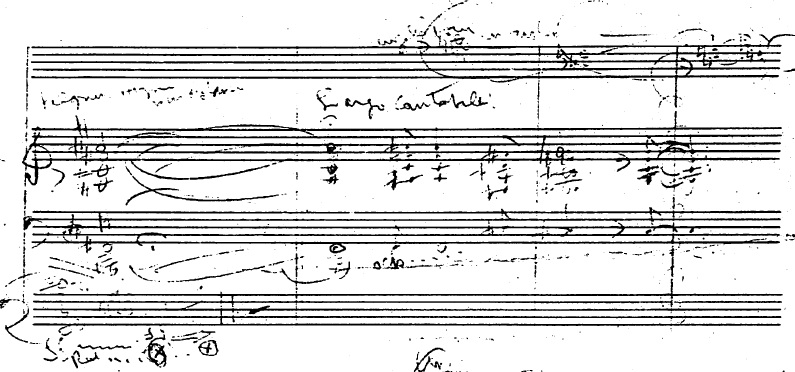

Even more controversial are the extra dissonant thirds played in high register during the quotation of the hymn “Martyn” when it appears in Hawthorne in the key of F#. Ives toyed with these thirds in an early sketch (f3956):

Next to and in explanation of these thirds you can scarcely make out at the top, in Ives’s scrawly handwriting, “angels join in distance,” which is a programmatic reference to Hawthorne’s short story “The Celestial Rail-Road” – it took me many trips to Yale’s Sterling Library to decipher what he wrote on the original sketch, and I later found it confirmed in a Kirkpatrick transcription. Ives later included some of these thirds in his piano piece based on Hawthorne The Celestial Railroad, and developed them even further in the analogous passage in the second movement of the Fourth Symphony. But he didn’t include them in the 1920 score, and, after a quarter-century’s deliberation (very sadly, in my opinion), opted not to use them in the 1947 score either. Yet Kirkpatrick, who didn’t include them in his 1945 recording, added them to his 1968 recording, whence many fans like myself became irrevocably accustomed to them, and found them perfectly evocative and, even more, entirely Ivesian. A certain performance tradition has grown up around them, and out of my 19 24 recordings, eight nine of the pianists include them.

And so, along with a few other less obvious variants, these are the three touchstones around which my choices among the recordings revolve. Of the recordings I own, the statistics come down as follows, listing what is included in each:

Pierre-Laurent Aimard: flute, viola, angels

Easley Blackwood: flute, no viola, no angels

Donna Coleman: flute, no viola, angels

Jeremy Denk: flute, no viola, no angels

Nina Deutsch: no flute, no viola, angels

Peter Geisselbrecht: no flute, no viola, no angels

Bojan Gorišek: flute, viola, no angels

Marc-André Hamelin 1988: no flute, no viola, no angels (but liner notes by myself)

Marc-André Hamelin 2004: flute, no viola, no angels

Herbert Henck: flute, viola, no angels

John Jensen: flute, viola, no angels

Gilbert Kalish: flute, viola, angels

John Kirkpatrick 1945: no flute, no viola, no angels

John Kirkpatrick 1968: no flute, no viola, angels

Aloys Kontarsky: flute, viola, no angels

Alexei Lubimov: flute, viola, angels

Steven Mayer: no flute, no viola, angels

Alan Mandel: flute, viola, no angels

Giorgio Marozzi: flute, viola, no angels

Yvar Mikhashoff: flute, no viola, angels

George Papastavrou: flute, no viola, no angels

Robert Shannon: no flute, no viola, no angels

James Tenney: flute, no viola, no angels

Nicholas Zumbro: flute, no viola, angels

(I’ll add the Jensen and Szidon when they arrive.) So 18 out of the 24 include the flute, and of those, nine also have the viola. Interestingly, the European pianists have been the most literal, insisting on the extra instruments and omitting the angels; perhaps they’ve had less trouble affording the extra performers. My own, admittedly subjective, ideal recording would contain the flute and angels but no viola, though I don’t object strongly to the viola. The only one three that matches my ideal in that sense is are the Donna Coleman, Nicholas Zumbro, and Yvar Mikhashoff. But another statistic to be taken into account is the timing of the movements, and especially Emerson, which varies widely in duration, ranging from 12 minutes to 19. At 50:19, Coleman’s is the second-slowest recording I own, next to Marozzi at 54:35, and there is a recording I don’t have just got, by Bojan Gorisek, that weighs in at a hefty 62:14, with a Thoreau of more than 21 minutes, eight minutes longer than any other recording – I’m almost afraid to hear it it’s kind of mesmerizingly hypnotic, with quarter-note = 15 during the A-C-G ostinato sections. Curiously, the shortest two recordings are both by Kirkpatrick, except for Kontarsky’s furiously rushed (at 35:58, though mostly very effective) reading. (As you would imagine, Kirkpatrick’s collector’s-item 1945 vinyl recording also uses more of the 1920 score than any of the others.) Denk’s recent and widely celebrated recording is a very literal reading of the 1947 score, as though he’d never listened to another recording, and I particularly love the way he recorded the flute, almost in the background as if it is emerging from the listener’s subconscious. The recordings I don’t have are by Werner Bärtschi, Louise Bessette, Jay Gottlieb, Ciro Longobardi, Philip Mead, Roberto Ramadori, Manfred Reinelt, Per Salo, Richard Trythall, and Daan Vanderwalle. I may buy a few more if I can, but plan to go to no extreme lengths to obtain them. A review here made me curious to hear the Longobardi, but Italian Amazon will not deliver it to my address.

Based on Ives’s oft-made comments about Emerson never having felt completed, some scholars, such as Stephen Drury (in his introduction to the Dover score) and Sondra Rae Clark (in her 1972 dissertation “The Evolving Concord”), have expressed a belief that the Concord is open-ended, and that no version is definitive. I agree to a point, with the exception that I think Ives also made it clear that he preferred the 1947 score to the 1920 in every way, and that the variants in the earlier edition are never equal, let alone better. I do think that the pianist who takes on the Concord needs to look through the manuscripts and especially the 17 scores from the 1920 edition into which Ives penciled variants and further ideas. I’m all for variations in performances of the Concord, and to each pianist his or her own personal edition. But I also often find clear musical reasons why one version is stronger than another. The authentic versions of the Concord are varied, definitely, and delightfully so, but – in terms of notes played – not infinite.

UPDATE: Oh, and if you do know of a recording I haven’t mentioned here, I would be grateful if you’d bring it to my attention.

UPDATE: Just found mention of old recordings by Rene Eckhardt, Ronald Lumsden, and Tom Plaunt.