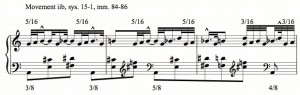

God knows I think Charles Ives is god – or rather, Charlie knows I worship him – and I bristle like hell when he’s called an amateur, but I have to admit his rhythmic notation makes me tear what’s left of my hair at moments. Below are mm. 84-86 as taken from the second movement of the Piano Sonata No. 1, and below that the corrected rhythmic notation as I feel sure he intended it:

In the original, the first half of the first measure has only seven 32nds duration in the right hand, and the second half of the second measure has twelve 32nds instead of eight. Now, poor Lou Harrison edited this from the manuscript, and perhaps the mistake is his addition. But Ives does seem to get befuddled when he starts using 32nd-notes and 64th-notes, and I’m not convinced that his conception of a double-dotted note matches what most of us think it is. I’ve made my alterations based on how the rhythmic motive plays out in the rest of the passage, and on how the two hands are laid out relative to each other. The point is to show how Ives used ragtime rhythms and motives to create static textures of phrases going out of phase with each other.

I’m analyzing the First Sonata to have something to use as a contrast to the Concord, and that chapter is threatening to become an entire second book. I have to guiltily admit, too – I think I slightly prefer the First Sonata to the far more celebrated Second. Jeremy Denk tells me that the First is harder to play. And there are many places in it where I recoil from what’s on the page and think Ives clearly meant something else. We’ve never had a clear, fully professionally engraved score of either work, nor are likely to in the forseeable future.