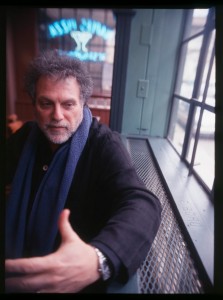

Composer Martin Bresnick gave a composers’ forum at Bard tonight that was absolutely fabulous. He played recordings of the most compelling music I’d yet heard of his – Every Thing Must Go for sax quartet, Prayers Remain Forever for cello and piano, Ishi’s Song for piano, and some faculty played his *** for clarinet, viola, and piano – and his manner of explaining his music was understated, humble, yet inspiring. When someone commented with surprise on the simplicity of his recent pieces, he replied, “I don’t write ‘modern music.’ I write my own music,” and I silently thought, “Yes! Yes! Yes! This is exactly what our students need to hear!” It renewed my faith in the value of bringing composers to talk to students.

Composer Martin Bresnick gave a composers’ forum at Bard tonight that was absolutely fabulous. He played recordings of the most compelling music I’d yet heard of his – Every Thing Must Go for sax quartet, Prayers Remain Forever for cello and piano, Ishi’s Song for piano, and some faculty played his *** for clarinet, viola, and piano – and his manner of explaining his music was understated, humble, yet inspiring. When someone commented with surprise on the simplicity of his recent pieces, he replied, “I don’t write ‘modern music.’ I write my own music,” and I silently thought, “Yes! Yes! Yes! This is exactly what our students need to hear!” It renewed my faith in the value of bringing composers to talk to students.

But what moves me to write is a story my colleague John Halle afterward told me he’d heard about the composer Ben Weber. Maybe someone can confirm it. Weber (1916-1979) was an American twelve-tone composer who managed to make the technique sound energetic and jaunty; I particularly admire his Piano Concerto, and he seems all but forgotten today, partly because he worked as a copyist rather than in academia. So the story was, apparently Aaron Copland [or apparently Virgil Thomson – see comments] met Ben Weber. Both were gay. Copland started out, “So, Mr. Weber, I hear you’re ‘one of us.'” “That’s right, Mr. Copland,” Weber said. “And I hear you write twelve-tone music.” “Yes, that’s true too, Mr. Copland.” “Well,” Copland replied, “…you’ll have to make a choice.”

It had to be the ’50s; gay twelve-toners were not so rare from the ’60s on (and Copland later went dodecaphonic himself). But it encapsulates a certain moment in American music.