I’m teaching my Analysis of Minimalism seminar this semester, and I have never had a group of students (eight of them) who came in already knowing so much about the repertoire we were dealing with. They bring up pieces I hadn’t planned to mention and occasionally even one I hadn’t heard of, and I have to think quick to stay one step ahead of them.

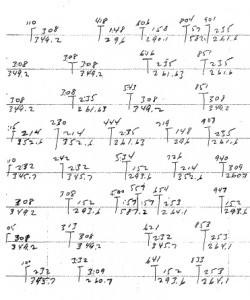

What I enjoy doing most in my analysis seminars is figuring out music I’d never analyzed before. I let them do the work for me (or if I end up doing it myself, I assume they’ll learn from watching me), and this class is certainly obliging. For the first time I’m analyzing scores by Phill Niblock, some of which are included with his CD liner notes. For instance, the following stack of random-looking numbers is the beginning, about half the score, of his 1980 piece for eight overdubbed flutes, titled SLS after the initials of his soloist Susan Stenger, on the XI disc Four Full Flutes:

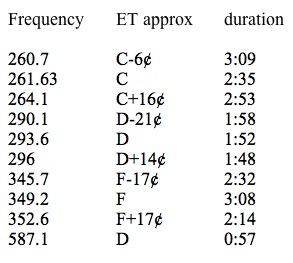

(Click on the image for better focus.) With just this to go on, the students figured out that the top numbers in each line above the little T marks (110, 418, 606 in the first flute) are the timings of the piece: 1:10, 4:18, 6:06. The upper number above the horizontal line following each one is the duration of the note in minutes and seconds. The bottom number, below the bottom line, is the frequency of the pitch, since Niblock never uses musical notation, but writes directly in cycles per second instead. We worked out that there are only ten pitches used in the 20-minute piece; three of them, C, D, and F, are based on frequencies from the conventional equal-tempered scale, and others are tuned upward or downward a few cents:

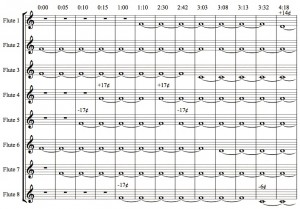

In addition, as someone in class figured out, each pitch at a certain frequency lasts the same duration every time it comes back: the pitch 260.7 cps always lasts 3:09, 345.7 cps always lasts 2:32, and so on. We figured out how we could make something of a readable score from this sloppy accounting sheet, and that, with the timings across the top, it would look something like this:

(Here’s this much of the piece to listen to, although you really need to hear the whole twenty minutes to appreciate the overall shape.) At least this translates the number score into something that we can follow with the timer and hear somewhat, although this hardcore minimalist essay can really only be experienced, not analyzed by ear. But we’ve figured out that Phill does seem to start pretty much with equal temperament as a basis, and that while some of his pieces have a gradual process going (as does Five More String Quartets, which we looked at the number score of as well), SLS has a more whimsical, less logical form.

The other day we used Neo-Reimannian analysis to compare the chord progressions in movement 2 of Phil Glass’s Low Symphony to those in Einstein on the Beach, and then we traced the course of the ubiquitous four-note rhythmic motive on which John Adams’s Phrygian Gates is based. This week we’re finally analyzing Gavin Bryars’s The Four Elements, which I’ve always wanted to do, a fabulous piece. It’s the closest thing I’ve ever had to a graduate-level seminar at Bard, because the students walked in the door already loving the repertoire. And it’s such a cool new world of music to analyze, I can’t believe most music departments want to opt out of it.