I didn’t anticipate that I would arrive at anything new to say about Robert Ashley in my paper about him at last week’s minimalism conference at Cal State Long Beach. But as it happened, the attempt to talk about him in a minimalist context elicited some insights I hadn’t had before, and as some previously Ashley-dubious audience members claimed to find them persuasive, I decided to post the paper here. Also probably at the Society for Minimalist Music website as a PDF, but here I can link to the audio examples.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

“Eventfulness is really boringâ€: Robert Ashley as Minimalist

by Kyle Gann

I hope it does not seem merely opportunistic to appear with a paper on Robert Ashley as minimalist just after I have published a book on Ashley. One of the things I find historically fascinating about minimalism is the magnetic field it cast on all sides, attracting some composers and repelling others, to the point that some composers whom we do not consider part of the movement led careers that we cannot adequately describe without alluding to it as explanation. Morton Feldman is certainly one of these, perhaps James Tenney, and also Robert Ashley. (For instance, my composition teacher Peter Gena recalled, in the early 1970s, being anxiously called into Feldman’s office to look at sketches for his newest piece. Feldman asked fearfully, “Do you think it sounds too much like Steve Reich?â€)

In 2009 I interviewed Robert Ashley for a book I was writing about him. He made a statement that rather surprised me, and I want to play you the audio because his delivery is so evocative:

The only thing that’s interesting to me right now is that, up to me and a couple of other guys, music had always been about eventfulness: like, when things happened, and if they happened, whether they would be a surprise, or an enjoyment, or something like that… And I was never interested in eventfulness. I was only interested in sound. I mean, just literally, sound in the Morton Feldman sense…. There’s a quality in music that is outside of time, that is not related to time. And that has always fascinated me… A lot of people are back into eventfulness. But it’s very boring. Eventfulness is really boring. – (Interview with the author, June 11, 2009)

As composers of his generation go, Robert Ashley is not someone often thought of as a minimalist. In fact, a case for the polar opposite would be easy to make. At a certain period in his career he earned a reputation as being the prime exemplar of what we then liked to call information overload. For instance, the initial 1979 version of his opera Perfect Lives, as recorded on the famous “Yellow Album,†was pretty spare, but by 1982 he had overlaid the piece with so many layers of musical activity that the original became difficult to locate beneath the multi-channeled audio surface. His next opera, Atalanta, was a chaos of improvisation. In Foreign Experiences Ashley underlaid his text and music, in the first act, with a 12-tone piano sonata he had written decades earlier. Ashley’s opera Improvement: Don Leaves Linda is entirely based on a fanatical precompositional scheme involving a 24-note row. When I interviewed him about the piece in 1991, he added, “Of course! I’m a serialist! What else would I do?†In the introduction to his book Outside of Time: Ideas about Music, titled “Speech as Music,†he wrote:

For some reason that I have never understood (and don’t fully understand today) I have always been attracted to music that is irrationally difficult. I don’t mean difficult in terms of endurance or effects. I mean difficult in the sense that there are many things going on at the same time… What I think today my problem came from is that even in piano music, when there are a lot of things happening very fast… the complexity resembles the complexity of speech. I came to discover very gradually that I was fatally attracted to the complexity of speech…. (Ashley, Outside of Time, p. 38)

He goes on to make a veiled complaint about minimalism, that around 1970, there was an “official announcement from New York and Washingtonâ€: “The announcement said simply, there is a new kind of music; it is very simple; everybody will come to understand, and we will forget about all of that foolishness that has been going on.†(Outside of Time, p. 54) The references to New York and Washington seem to refer to the performing space The Kitchen, the New Music America festivals, and, more explicitly, the creation of the National Endowment for the Arts. (He and I were on opposite sides of a generational divide in that issue.)

At the same time, though, Ashley included in Outside of Time another new (2004) article titled “to begin again with ‘music,’†in which he talked about the central ideas that had always been crucial to his music, beginning with the “drone conceptâ€:

I use the term “drone” to mean any music that seems not to change over time. Or music that changes so slowly that the changes seem almost imperceptible. Or music that has so many repetitions of the same melodic-harmonic pattern that the pattern is clearly secondary to another aspect of the form. (And I use the term “drone†though from the beginning it has often been used by critics in its pejorative sense, meaning “nothing is happening.â€) (Outside of Time, p. 96)

It is clear that Ashley thinks all of his music has been drone music (as opposed to what he calls “timeline music,†meaning everything else), even when it doesn’t contain anything that we minimalism scholars would think of as a drone.

Bob doesn’t know I’m giving this paper, and it may be that he would disagree with my premises here. But he and I have disagreed before, and in fact he raises quite a public disagreement with me in the introduction I quoted from. To take issue with him a little bit, then, it did seem to me, at the time of the 2009 interview, that Ashley’s claim that he had only been interested in “sound, in the Morton Feldman sense†was something of an illusion of hindsight. In a 1961 interview in Source magazine, Ashley once claimed that subsequent to John Cage’s use of empty time structures, the guiding metaphor of music was now no longer sound but time, and the ultimate result might be “a music that wouldn’t necessarily involve anything but the presence of people… It seems to me [he famously continued] that the most radical redefinition of music that I could think of would be one that defines ‘music’ without reference to sound.†Like many other composers in the 1950s, Ashley had been highly impressed by Cage’s use of empty time structures, the lengths of which were determined in advance before the sounds within them were composed. I have sometimes referred to Cage’s works of this period as being proto-postminimalist, in that they seemed to anticipate postminimalist music rather than minimalism per se. If that is admissible, then we could say that Ashley’s works inspired by Cage’s time structures might be neo-proto-postminimalist, and by a musicohistorical arithmetic that should put them somewhere in the minimalist ballpark. [This was a joke, and appreciated as such. In fact it became a running gag of the conference.]

Born in 1930, Ashley is a little older than the oldest composers we consider card-carrying minimalists, but he knew about the style almost from its origins. He directed the ONCE festival from its beginnings in 1961, and two of the original minimalists, La Monte Young and Terry Jennings, were featured at the second ONCE festival in 1962; Jennings, already a heroin addict at the time, ended up staying at Ashley’s apartment for awhile. While there is no discernible direct influence of their music on his, a couple of Ashley’s better-known ONCE festival pieces were, in fact, explicitly repetitive and extremely restricted in their materials. One was She Was a Visitor, the finale of his opera That Morning Thing (1967), in which the narrator repeats the title phrase over and over as the other performers extend the phonemes of the phrase into a sibilant continuum, sustaining each sound for one full breath. This piece seems to me incontrovertibly minimalist.

A conceptually similar piece called Fancy Free (1969) was written for the stuttering voice of Alvin Lucier, who was supposed to read the text over and over as four cassette recorder operators recorded his speech and played back fragments of it. There is an obvious conceptual similarity here to Lucier’s own piece I Am Sitting in a Room, also based on a repeating text. And it is worth re-emphasizing that Tom Johnson’s first use of the word minimal to describe music (in the Village Voice of March 30, 1972) was applied to music not by the composers we now think of as minimalist, but to works of Alvin Lucier and Mary Lucier.

Almost from the beginning, Ashley’s music involved the setting up of certain chunks of time, the sounds to fill them being decided upon later, but this determination was often made via group collaboration. Within the conceptualist milieu of the ONCE festivals, what was most distinctive about Ashley was that he seemed less interested in sonic patterns than in the social situation of the performance. Far from being interested in “sound in the Morton Feldman sense,†many of his early pieces allow the performers to choose the sounds, and show an almost total lack of interest on Ashley’s part as to what the sounds are. The combination of this attitude, along with his use of uniform time units and repetition, sometimes results in what one might call a “randomized minimalism,†in which the gambit of sounds within a piece is closely circumscribed, the process might be subtle and gradual, but the sounds might be anything at all.

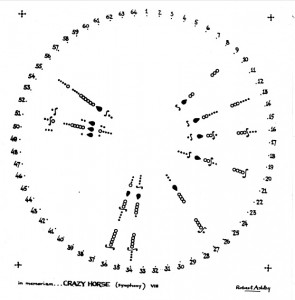

Ashley’s most famous ONCE composition, The Wolfman (1964), involves singing single notes of 13 seconds each, changing within each breath one aspect of the sound (either pitch, loudness, vowel, or closure). Amplified up to maximum feedback, the piece may have a maximalist noise component, but as experienced by the performer it is as tightly disciplined and as limited in its possibilities as many early minimalist classics. in memoriam…CRAZY HORSE (symphony) (1961-2) is structured as a series of regular pulses in which the players are supposed to sustain a so-called “reference sonority,†changing some aspect of it as certain symbols come up in the circular performance chart.

A 1966 recording of the work on the Advance label [click for audio] was chaotically noisy, yet gradual in its transformations. However, in 2007 the Ensemble MAE in Holland produced a recording of a very similar piece in the same series, in memoriam… ESTEBAN GOMEZ (quartet), using a drone with a consonant major third as their reference sonority. This recording sounds classically minimalist, and in fact rather similar to James Tenney’s Critical Band, which I think of as really hard-core minimalism. In short, there is nothing in the description of these pieces that precludes a minimalist-sounding realization. This comparison is our first hint today that, as dissonant and modernist as they seemed in the original performances, some of Ashley’s early ONCE festival works were minimalist in concept, and could be made to sound classically minimalist merely by a change in the materials chosen by the performers.

* * * * * * * * * * * *

The second phase of Ashley’s music begins in 1979 with the first of his mature operas, Perfect Lives. Almost all of Ashley’s operas have certain minimalist aspects, usually limitations of tempo, rhythmic structure, or harmony, and it would be easy to cherry-pick passages that sound minimalist or at least repetitive. For instance, in the five operas Perfect Lives, Improvement, Atalanta, eL/Aficionado, and Now Eleanor’s Idea, the tempo is always 72 beats per minute throughout. The tempo in the remaining opera of this group, Foreign Experiences, is 90 beats per minute. The duration of each opera is set in advance. Each of the seven scenes of Perfect Lives was intended to be 24 minutes and 40 seconds, which in 1979 was the legal minimum length of a half-hour television show, allowing for commercials. Originally, each of the four operas of the tetralogy Now Eleanor’s Idea was supposed to be 6,336 beats long, which is 88 minutes (4 acts at 22 minutes each) at a tempo of 72 beats per minute. (eL/Aficionado was exempted from that requirement because it was not originally composed as part of the tetralogy, and its tempo is not continuously articulated.) I’m sure there’s probably someone who knows how many beats there are in the score of Wozzeck or Der Rosenkavalier, but the fact that the number of beats in some of Ashley’s operas is easily calculated speaks volumes about his working methods.

Each scene of Perfect Lives follows a single rhythmic template throughout. The first episode, “The Park,†has a 13-beat meter, “The Supermarket†five beats, “The Bank†nine, and so on. In quite a few passages this results in a repetitive ostinato running through a scene for several minutes at a time. In addition to the rhythmic units, harmonies are also often structured repetitively. Atalanta, a monumental work, is performed entirely over a progression of six chords: Bb, Ab, G, C7, Eb, Bb. This is not always apparent because of the improvisatory latitude granted the performers, but the chord changes theoretically come at regular intervals. Harmonically, eL/Aficionado is based entirely on a repeating series of 16 chords, in four groups of four, each group unified by a single scale:

In the scenes of the opera that are titled “My Brother Called†(scenes 2, 3, 5, 6, 8, and 10), the chord changes every 18 beats, or every 15 seconds, and one line of text is sung over that chord. In addition, while the singer Thomas Buckner improvises his lines within the scale, the initial note of each phrase is determined by a repeating sequence, given in half-notes above. The first scene of Dust (1998) has simple chords repeating in an isorhythm of 1, 2, 3, 5, 3, 2, 1 lines, the rhythm repeated over and over again.

One of Ashley’s most conceptually minimalist works is the opera Celestial Excursions. Although it’s also one of his most musically elaborate works, the entire piece uses only the C-major scale. Each scene is based a certain chord, with different reciting tones for the singers, and the scenes differ harmonically by having a different note in the bass – and that note is never C, so there’s never a feeling of resting on the tonic. This is an overall structure very similar to Steve Reich’s Music for 18 Musicians.

Of course, what keeps people from thinking of these pieces as minimalist is most obviously the text. Were we to listen to them without the text, long passages might take on a minimalist aura, but the speaking of a text over a static background tends to preclude any impression of minimalism. Text tends to be linear and unidirectional. We listen to hear what will be said next. There are clearly minimalist text pieces, by Jackson Mac Low and others, but they tend to be restricted to few words, with much repetition and a Gertrude Stein-ish disregard for syntax. Ashley’s opera texts are not of this nature; indeed they tend to be incredibly verbose and extended, with long stories.

However, Ashley’s idea of opera, to the extent we’re inclined to acquiesce to it, is that speech is music, and that we do not listen to it for meaning alone. Several operas deal with the tendency of profanity – that is, intentionally meaningless words – to slow down thought, and as he asks rhetorically in Atalanta, “Who could speak if every word had meaning?†The texts are filled with gentle nonsequiturs and incomplete word-pictures. Each phrase means something, but the totality of what the text means is more than usually in doubt. In other words, Ashley’s texts are narrative in appearance, but he uses a variety of devices to render their narrativity ambiguous. While he denies that his writing is stream-of-consciousness, he also denies that an opera can have a plot. Ashley’s operas do possess background plots, but those plots are rarely inferable from the text of the opera; they are best read in the liner notes. As he has written,

At the opera I am transported to a place and time where there is no disorder. There is disorder on stage, and it is called melodrama. We don’t believe it. This is important: that we don’t believe it. We do believe… what happens in the movies…. Therefore, opera can have no plot. It is foolish to argue that opera – any opera – can have a plot; that is, that the “characters†and their apparent “actions†and the apparent “consequences†are related in any way. Opera can be story-telling only. (“The Future of Music,” unpublished typescript delivered April 15,2000, p. 9)

This may not convince the dubious that Ashley’s words are simply melody, though he often speaks as though he believes that’s the case. At least one can say that the time element in Ashley’s texts is frequently unimportant, that one statement does not lead to another, nor one episode need to be previous to another episode for the sake of understanding. Ashley’s words, frequently nonlinear and read in his own calmly inflected voice, or chanted on or around one note, can be heard in themselves as a kind of randomized minimalism. We will come to a perhaps more convincing example shortly.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

However, when we move to the most recent phase of Ashley’s music, the parallels to minimalism become more and more striking. As modernism moved, from its heyday in the 1950s or ‘60s, to minimalism and the New Tonality, so did Ashley’s music move from often maximum confusion and chaos to more meditative continua. This has been especially true of his non-operatic works, starting from 1988 on with his flute concerto Superior Seven. Ashley’s late instrumental works are in a style that I would called randomized postminimalism. That is, the choice of pitches is limited, the tonality usually clear, the rhythm based in a steady pulse, but within the available gamut the note-to-note choices are determined by random or quasi-random procedures. In his piano piece Van Cao’s Meditation and the ensemble piece for Relache Outcome Inevitable, the order of notes was determined by a systematic document Ashley had been using in the early 1960s for the ONCE festival pieces, what he calls an “encyclopedia of proportions and combinations†of the numbers 1 through 5. Although he’s used it for many pieces, the document mysteriously disappeared about the time I came to write the book on him, and I’ve never been able to take a look at it – kind of a strange thing given how neat and well organized most of Ashley’s files are.

Van Cao’s Meditation (1992) was inspired by a photo of Van Cao, the composer of the Vietnamese national anthem, sitting at what was supposedly one of only two pianos in the country at the time. The music is made up entirely of 8th-notes on the pitches Bb, C, Db, Eb, and Fb, with an occasional fermata-laden cadence on some octave A-flats:

Texturally and tonally the piece is minimalist in the extreme, but the ordering of pitches is completely inscrutable.

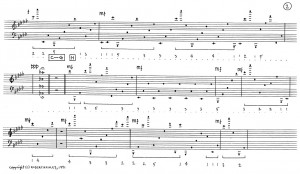

Outcome Inevitable (1991), for the Relache ensemble, is grounded in an insistent repeating middle C in the bass. The rhythmic structure is determined by repeating rhythms tapped out softly on a bass drum in odd groupings. The series of changing rhythms outlines a seven-part structure, each part of which features a solo by a different instrument. The melodies all consist merely of rising scales interrupted by occasional leaps (or steps) downward to keep the line within a fairly narrow range:

(Audio example here.) Each phrase consists of a small random number of 16th-notes (up to 6) leading to a sustained note. Lasting 16 minutes, the piece is a lovely evocation of timelessness, drawn from a clear and endlessly elaborated idea, but quite unpredictable in its details.

In When Famous Last Words Fail You (1997), written for singer Thomas Buckner to sing with the American Composers Orchestra, the entire orchestra plays only the pitch A in various octaves; the conductor does not beat time, but merely controls volume, as the instruments are cued by key words in the singer’s text. Unwilling to do this at the premiere, Dennis Russell Davies did not rehearse the piece well, and gave what Ashley considered a miserable and misleading performance. The piece has never been heard as it was intended, but surely an orchestra piece using only one pitch merits some mention in a history of minimalism.

As for the operatic works, in 1998 Ashley began devising strategies to sabotage the narrativity of his own texts. One of these is the application of more than one text at a time. The stories in Dust (1998) are chanted by each soloist above four other lines chanted by the other singers. Celestial Excursions uses similar techniques, and also includes a scene in which two songs are heard at once, one a country-and-western love song and the other a Renaissance sonnet. In his current opera Quicksand, Ashley is experimenting with a technique of reading the line while passing quickly past the microphone, so that each phrase takes on the envelope of a quick motion, a kind of Doppler effect; in the excerpt I heard performed live, the meaning sometimes became indistinguishable. One of the most striking examples of textual sabotage is the short opera Your Money My Life Goodbye (1998), one of Ashley’s most minimalist works. (Please listen to the first excerpt before reading the following description.)

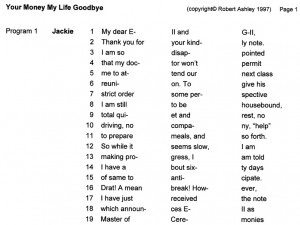

The musical accompaniment is a series of pulsing A-flat major triads at a pulse of 216 per minute. The text comprises 892 lines of seven syllables each, each line divided 3+2+2, with no line hyphenated over to the next:

Each vocal line is meant to be read in a rhythm that parallels that of the title, “Your money, my life, good-bye.†(The opera Concrete will use a similar verbal isorhythm.) There are 15 pulsing chords per vocal line; I think no one would ever notice this simply listening to the piece, but if, starting from the first note, you conduct the pulsing chords in 15/8 (that is, five groups of three), you can predict the onset of each phrase. Since I have realized this, I have found the text much more difficult to understand – I fall into the habit of listening to it as merely phoneme-inflected rhythm. (Now listen to the first excerpt again.)

Your Money My Life Goodbye does have a plot about a spy married to a nefarious woman financier who brings down large corporations a la Bernie Madoff – and this a full decade before Madoff became a synonym for fraud. But if you listen to the text in seven-syllable increments, it can virtually cease to be heard as text and sound like a repeating rhythm, like those optical illusions that can be seen either as a vase or as two faces. The effect illustrates perhaps better than anything in Ashley’s output his idea of speech being musical in and of itself. Towards the end of the work, in another complication, a bass ostinato starts grouping the chords into a syncopated 6/4 meter. Thus the text marks off chords in groupings of 15, and the ostinato creates a harmonic rhythm of 24 chords, for a quite complex but minimalistically steady five-against-eight cross-rhythm. I think we may have to call Your Money My Life Goodbye the most hard-core minimalist opera since Einstein on the Beach.

In addition, Ashley’s second recording of Atalanta, made in 2010, twenty-five years after the first recording, shows how far Ashley’s style moved towards minimalism in that quarter-century. The 1985 version is particularly chaotic by Ashley’s standards, though there are passages, such as this one, in which the six repeating chords and the recurring melody are clearly audible. By the 2010 recording, though, improvisation is absent, and the electronic backgrounds engineered by Tom Hamilton are consistent and predictable. In the first scene, “The Etchings,†each chord lasts five minutes. In “Empire,†of which we’ll hear an excerpt here of the first chord going into the second, the music takes more than half an hour to move through the six chords only twice. The second compact disc that contains the series of stories called “Au Pair†(text by Jacqueline Humbert) is entirely on an E-flat chord. Ashley unifies the stories by a motive of two rising half-steps, and each story continues the upward chromatic scale where the previous one leaves off, a very subtle kind of additive process.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Ashley’s lifelong commitment to both complexity and the drone concept make him an interesting, not-very-minimal-sounding minimalist. Over the decades, the drone concept has remained a constant in his music, while the complexity, if never absent, has gradually become more transparent, a randomization of details rather than an overloading of layers. Ashley’s born-again Feldmanism in later life may have colored his early intentions through 20-20 hindsight, but his relentless pursuit of uneventfulness has eventually turned him into a wary, reluctant, perhaps even unintentional minimalist, but a minimalist nonetheless.