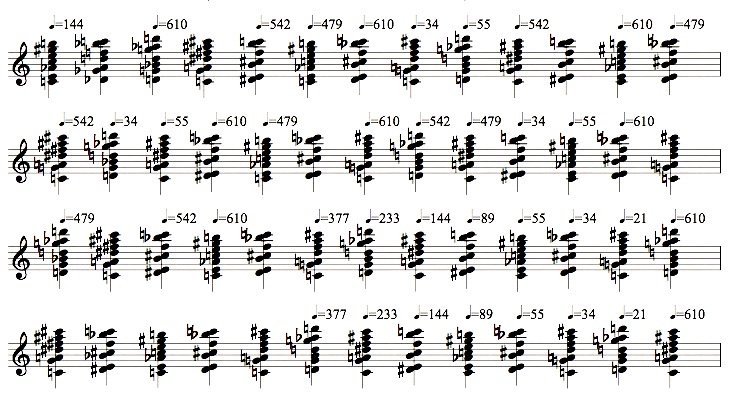

A new, brief piece, a rhythm study: Mystic Chords, 6:20. It’s the most austere thing I’ve written in decades. The main idea of the piece is an attempt to determine rhythms not by duration, but via tempo, thus creating rhythms incapable of metric notation. Here’s an excerpt from the score:

These aren’t the actual pitches. The piece uses a rather wonderful symmetrical pitch set I discovered, 27 harmonics above an extremely low F#, specifically harmonics nos. 1, 3, 5, 7, 9, 11, 13, 15, 21, 25, 27, 33, 35, 39, 45, 49, 55, 63, 65, 77, 81, 91, 99, 117, 121, 143, 169 – or rather, octave transpositions of those harmonics. I’m not much into symmetry; I usually prefer quirky pitch constructions with a scattering of elements that only appear once or twice. But this set creates seven identical chords based on the 1st, 3rd, 5th, 7th, 9th, 11th, and 13th harmonics, containing those same harmonics in each chord.

I called the piece Mystic Chords because I spaced all the chords in fourths after the manner of Scriabin’s famous “mystic chord” – C F# Bb E A D, and I added a G on top. The actual harmonics, then, are stacked as follows, with each chord running vertically:

768Â Â Â Â Â 768Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 800Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 728Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 792Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 792Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 728

576Â Â Â Â Â 576Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 560Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 560Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 576Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 572Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 572

416Â Â Â Â Â 432Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 440Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 392Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 432Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 440Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 416

320Â Â Â Â Â 312Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 320Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 308Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 324Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 308Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 312

224Â Â Â Â Â 240Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 240Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 224Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 234Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 242Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 234

176Â Â Â Â Â 168Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 180Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 168Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 180Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 176Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 169

128Â Â Â Â Â 132Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 130Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 126Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 126Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 132Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 130

The preceding won’t mean anything to non-math geniuses, but dividing each number by the largest possible power of two gives the octave equivalents:

3Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 3Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 25Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 91Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 99Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 99Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 91

9Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 9Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 35Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 35Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 9Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 143Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 143

13Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 27Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 55 Â Â Â Â Â 49Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 27Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 55Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 13

5Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 39Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 5Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 77Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 81 Â Â Â Â Â Â 77Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 39

7Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 15Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 15Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 7Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 117 Â Â Â Â Â 121 Â Â Â Â 117

11Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 21Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 45Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 21Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 45Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 11 Â Â Â Â Â 169

1Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 33Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 65Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 63Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 63Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 33Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 65

Now it’s easier to see that the first column is all divisible by 1 (of course), the second by 3, the third by 5, the fourth by 7, the fifth by 9, the sixth by 11, and the last by 13. Each column contains that number multiplied by 1, 3, 5, 7, 9, 11, and 13, and thus the entire pitch set is all seven numbers multiplied by each other. It’s such an elegant construction, so simple in principle, that I fully expect to be told that someone else has already come up with it. Its benefit for me is that each horizontal line is made of of pitches close together, ranging no further than a whole step and in some cases a half-step. The following chart, showing the same pitches given as cents above the tonic F#, makes this clearer:

702Â Â Â Â Â 702Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 773Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 609Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 755Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 755Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 609

204Â Â Â Â Â 204Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 155 Â Â Â Â Â 155 Â Â Â Â Â Â 204Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 192Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 192

804Â Â Â Â Â 906Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 938 Â Â Â Â Â 738 Â Â Â Â Â Â 906Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 938Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 840

386Â Â Â Â Â 342Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 386 Â Â Â Â Â 320Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 408Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 320Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 342

969Â Â Â Â Â 1088 Â Â Â Â 1088 Â Â Â Â Â 969 Â Â Â Â Â 1044 Â Â Â Â Â 1103 Â Â Â Â Â 1044

551Â Â Â Â Â 471Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 590Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 471Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 590Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 551Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 481

0 Â Â Â Â Â 53 Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 27 Â Â Â Â Â 1173 Â Â Â Â Â 1173 Â Â Â Â Â Â 53 Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 27

And so I have seven tonalities, all related to the central tonality, each chord equivalent in content, with the horizontal lines moving in very small increments and pivot notes among any two chords. It’s a closed, fully transposable just-intonation system. And since harmonics 1, 9, 5, 11, 3, 13, 7 make up an overtone scale (easier to see renumbered 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14), there’s the possibility of deriving a thick web of melodic connections from these 27 pitches. (I could add in the 15th harmonic with only six more pitches, and might, since Harold Budd’s music made me so fond of major seventh chords.) In fact, this is almost the pitch set I used in my recent piece The Unnameable (of which I played the world premiere at the University of Northern Colorado last thursday, at a lovely festival of my music organized by composer Paul Elwood), except that there I used 15/14 instead of the 9th harmonic. Here I use those chords in an extremely minimalist way, but I think I’m going to have to explore them further.

I guess this will be mumbo-jumbo to most readers, but I’m excited about it as extending tonal harmony into new vistas in a surprisingly efficient manner. It took Partch 43 pitches to do what he wanted in 11-limit tuning, and I’ve got 13-limit with only 27. Of course, he used subharmonics and I don’t.