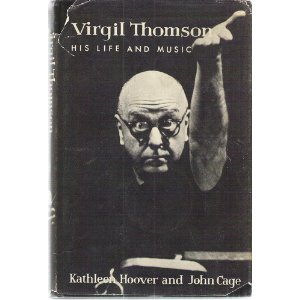

In Michigan a few weeks ago, I saw the second copy I’d ever seen of Kathleen Hoover’s and John Cage’s 1959 book Virgil Thomson: His Life and Music, in the possession of Thomson scholar Jennifer Campbell. The first copy I saw was in Thomson’s own apartment in 1989. I realized I had to have it, and of course was able to find a copy in pretty good shape via Amazon, for $75. Hoover wrote the biography, and Cage wrote about Thomson’s music, in tremendous detail. Were one of the authors not so famous, the book would not at all deserve republication. It’s the only writing I know of of Cage’s in which he subordinates his personality to his subject matter, in plain, expository prose. He’s stylish as ever, but flat, often euphemistic-seeming, searching for words and sometimes ending up without a point to justify his laborious cleverness. The discussion of Four Saints in Three Acts is about as unenthusiastic as I can imagine:

In Michigan a few weeks ago, I saw the second copy I’d ever seen of Kathleen Hoover’s and John Cage’s 1959 book Virgil Thomson: His Life and Music, in the possession of Thomson scholar Jennifer Campbell. The first copy I saw was in Thomson’s own apartment in 1989. I realized I had to have it, and of course was able to find a copy in pretty good shape via Amazon, for $75. Hoover wrote the biography, and Cage wrote about Thomson’s music, in tremendous detail. Were one of the authors not so famous, the book would not at all deserve republication. It’s the only writing I know of of Cage’s in which he subordinates his personality to his subject matter, in plain, expository prose. He’s stylish as ever, but flat, often euphemistic-seeming, searching for words and sometimes ending up without a point to justify his laborious cleverness. The discussion of Four Saints in Three Acts is about as unenthusiastic as I can imagine:

For the composition of Four Saints, Thomson applied a new creative method: seated at his piano, text before him, and singing, he improvised an entire act at a time until it became clear to him that the vocal line and harmony had taken stable form. This procedure placed faith in what he terms the “well-springs of the unconscious,” and does not view as a pollution the intrusion of individual taste and memory into those universal waters. [Interesting intrusion of Cage’s Zen ideas.] One may question the purity of such a modus, however, for the thematic relationships in his score are very knowing, and few of them differ from his earlier practices. This score stands apart from his previous Stein settings in that it defies analysis. Scholarly study of it yields nothing but statistics. These give the impression that the materials of music, in contrast to those of poetry, are becoming impoverished. There are 111 tonic-dominants, 178 scale passages, 632 sequences, 38 references to nursery tunes, and one to “My Country, ‘Tis of Thee.”…

Some find the opera too long, though its playing time is only ninety minutes. Actually, it is as long as might have been mathematically expected. Susie Asado is 3 pages; Preciosilla, 9; Capital, Capitals, 34; Four Saints (in piano score) takes up 144. The implication is a continuation of a series of works, respectively, 648, 3,240, and 17,826 pages long.

Have you ever seen a music writer sound so utterly bored and uninvolved? The book apparently caused quite an understandable rift in the Cage-Thomson relationship. However, there are nevertheless some wonderful glimpses of Thomson’s pithily reductive view of the world:

This was the period of WPA. With Orson Welles, John Houseman, and others, Thomson became part of the non-relief 10 percent professional assistance quota permitted. The group achieved a notable production of Macbeth, staged by Welles at the Lafayette Theater in Harlem with Negro actors and with voodoo chants and dances directed by Asadata Dafora Horton. Musical arrangements were assigned to Thomson, who orchestrated Lanner waltzes and worked out with Welles weather effects calculated to build up the sound of the actors’ voices. His original contributions were trumpet fanfares, one of which involved three players in the production of a tone-cluster. Then, as now, he was generally unenthusiastic about the musical possibilities of a Shakespearean script. “One can get in a little weather music,” he says, “and, once the characters are dead, sometimes a funeral. Otherwise it is mostly fanfares to get the actors on and off the stage.” He points out further that Shakespeare, initiating a theatrical movement in an England that had a strong and established musical life, had arranged matters so that his speeches and scenes would be forever free of competition from musical quarters.