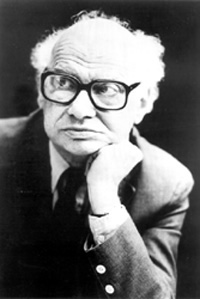

George Tsontakis just wrote to tell me that Milton Babbitt died this morning, just in time for me to get his death date into both my Ashley book and my introduction to the new edition of Cage’s Silence. I’ve written so much about him that I don’t have much left to say; it was a love-hate thing. I was looking up a reference in one of his Perspectives articles just this morning. The one time I met him (I was representing the ailing Nancarrow on a Babbitt/Nancarrow panel) he didn’t seem too thrilled. He was certainly a sharply-defined character. Had he not lived, we should have had to invent him.

George Tsontakis just wrote to tell me that Milton Babbitt died this morning, just in time for me to get his death date into both my Ashley book and my introduction to the new edition of Cage’s Silence. I’ve written so much about him that I don’t have much left to say; it was a love-hate thing. I was looking up a reference in one of his Perspectives articles just this morning. The one time I met him (I was representing the ailing Nancarrow on a Babbitt/Nancarrow panel) he didn’t seem too thrilled. He was certainly a sharply-defined character. Had he not lived, we should have had to invent him.

Archives for January 2011

How to Talk to String Players

I have now had a string quartet performed. The premiere recording of The Light Summer Land is up here and the performers are Ethan Wood and Megumi Stohs, violins; Sarah Darling, viola; and Josh Packard, cello. I am indebted to my composer friend Carson Cooman for arranging the performance. It went very well, though it almost didn’t. Luckily my composer friend Scott Wheeler came by for the dress rehearsal. Scott is not only a very good composer of operas and chamber music (he’s one of the ones who years ago insisted I refer to his music as “Midtown†rather than “Uptownâ€), but he’s worked with the Dinosaur Annex ensemble for 30 years as conductor and administrator. He knows how to talk to performers, and he also knows, as I don’t much, how players in an ensemble actually hear and interpret what a composer says to them. At the rehearsal, after a complete runthrough of the piece (I have a good memory for details of my pieces, and don’t like to stop an ensemble in flight), I went through section by section and marked things that I wanted to sound differently. When I finished, Scott came up and made more incisive and general comments about vibrato and dynamics. At dinner he explained to me:

“Performers like to be engaged on the level they understand. String players spend all their time in lessons obsessing over minutiae of vibrato and phrasing in traditional repertoire. When they play Brahms and Mozart, they feel ownership of their own performances, but when they come to our music, they leave responsibility to the composer, and if it sounds bad, it’s the composer’s fault. If you can get them to experiment with different levels of vibrato and dynamics and phrasing, they’ll take their own responsibility for making the music beautiful.â€Â

It seemed like good advice on the face of it, involving things I’d never thought of. I have a lot of experience with percussionists and pianists, not much with string players, and none, until now, with string quartets. And the proof was that the performance was 250% better than the rehearsal runthrough had been two hours earlier. And so I pass it along.Â

I also had once again an experience I’ve had before, of the performers telling me afterward, “Oh, now I understand the piece.†Why didn’t they understand it before? Because I don’t write music of crescendos and decrescendos and climaxes. I generally write flat-dynamic, impassive music of languid repetitions, nonsequiturs, brooding stillness. Very few string players ever play music by Satie, Virgil Thomson, Cage, Brian Eno, Feldman, John Luther Adams. They go their entire lives making dramatic crescendos followed by ritardandos, big up-and-down emotional curves. Several months ago I heard a group of excellent student players, who doubtless could have played the hell out of Brahms, make a perfectly lifeless hash of the Cage String Quartet. Clearly no one knew enough to coach them as to what the surface of the piece should sound like, limpid and radiant. Classical players: meet postclassical music. It’s different. Some of its paradigms are electronic or mechanical, and it doesn’t always breathe or climax. Luckily, Scott, who writes music very different from mine but who was close to Virgil Thomson (and who arranged an introduction for me to him just before the great man died), is catholic enough in his tastes that he looked at my score and intuited exactly what I was trying to do – and got that across to the players, who responded beautifully.Â

I took some risks in the piece, and some of them paid off better than I expected. I think there are a few continuity problems in the first half, which I’ve got plans to revise, but it was one of those pieces I needed to try out and hear live first. I’ve wandered into a style of minimalist collage, with adjacent process-panels, so to speak, whose logic of presentation may not be apparent in the short run. I think it worked out perfectly for me in Kierkegaard, Walking, but there are a few small missteps here, easily correctible, I think.Â

Of course, I’ve learned that expressing modesty is also a risk. In my Cage book I rather gallantly, I thought, attributed any originality in the book to the army of Cage researchers whose work I was bringing together into one narrative. This netted me a few reviews along the lines of “Nothing new to say, but at least he admits it.†(Actually, I know very well that the sources I wove together in that book were so farflung and so many of them from such obscure journals, that you would have to be a rabid Cage researcher yourself not to encounter several ideas in that book for the first time. One idiot at Amazon stated that if you’ve read Silence, you’ll find nothing new in my book on 4’33” – even though 4’33” is mentioned exactly once in Silence.) Modesty used to elicit compensatory compliments. Nowadays it encourages the small-minded to echo one’s low self-estimation. Nevertheless, justified modesty is a habit I prefer not to discard.

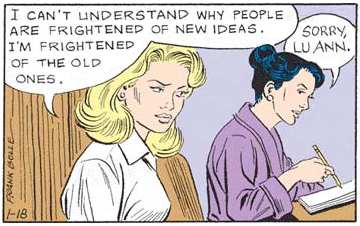

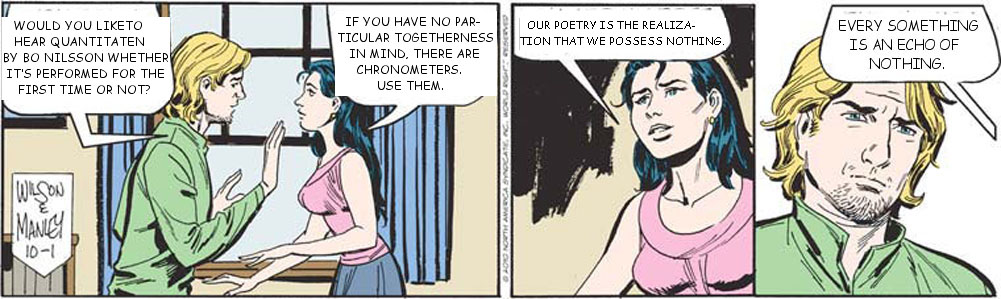

In Which the Mainstream Notices Us

Holy cow! The ancient comic strip Mary Worth quotes John Cage today!. And Josh Fruhlinger of Comics Curmudgeon (a very funny blog I’ve mentioned here before) responds to it with a 4’33” reference. It’s kind of a Hallmarky sentiment by Cagean standards, but I’m having fun picturing the comic with some other Cage quote in there. Like, “If you have no particular togetherness in mind, there are chronometers. Use them.” (h/t David McIntire, though I would have seen it myself by afternoon.)

UPDATE: I have to include Ernest Ambrus’s cartoon he sent in response. A whole book of these could be hilarious:

UPDATE 2: Ernest outdoes himself (and see comments):

It’s all that much funnier if you keep up with these strips to read Comics Curmudgeon. And, while I’m at it, what else have I got to do?:

Good lord, what have we begun?

UPDATE 3: And again:

The Difference Revealed

From today’s press release from Other Minds:

“In America, there is not enough angst!” Louis Andriessen once told the journalist K. Robert Schwarz.Â

I frequently daydream about moving to Europe. Then there are times that I think I should just stay in America. This pronouncement occasioned one of those times. I’ve heard this from Europeans before. What the hell is supposed to be so goddamn wonderful about angst?

Andriessen and I are both featured composers at Other Minds next month. And next October we are both giving keynote addresses at the Third International Conference on Minimalist Music. I think the topic of my address will have to be the advantages of life without angst.

There is nothing I work so hard on as ridding my life of angst. And I do it first in my music, in hopes that that will teach me how to do it in my life….

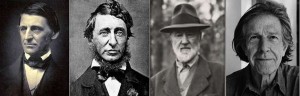

My Life as a Transcendentalist

Â

Â

In response to a question after one of my recent Cage lectures, I happened to mention Emerson, Thoreau, Ives, and Cage in the same sentence, and then said with a chuckle, “That’s the rectangle I’ve spent my entire life in.†This month it’s come to seem like more than a joke. I’m writing a piece of music about Thoreau, as a companion piece to my On Reading Emerson, for which I read a little of Thoreau’s journal each morning, which has given me quite a few sonic inspirations. For instance:

I am brought into the near neighborhood and am become a silent observer of the moon’s paces to-night, by means of a glass, while the frogs are peeping all around me on the earth, and the sound of the accordion seems to come from some bright saloon yonder. I am sure the moon floats in a human atmosphere. It is but a distant scene of the world’s drama. It is a wide theatre the gods have given us, and our actions must befit it. – June 2, 1841

I am also preparing for a seminar I’m teaching starting next week entirely on the Concord Sonata. We’ll be comparing the 1921 and 1947 editions of the piece with the original manuscript, as well as with other pieces based on the same material: Four Transcriptions from Emerson, The Celestial Railroad, and the Emerson Concerto. I’ve never felt like I fully grasped the “Hawthorne” movement, so one thing I’ve been doing in odd moments is entering it into Sibelius, note by note, both so every note will register with me, and also so I’ll have a MIDI file of it. On top of that I’ve been asked to write a foreword for a 50th-anniversary edition of Cage’s book Silence, which appeared in October 1961. So I’ve reread Silence for about the tenth time, and this time cover-to-cover and more intently than ever, trying to fix once and for all an impression of the book that has rotated wildly over the years.

So I’ve been immersed in these four figures, who for me epitomize what I love about America – and from whom America seems so distant these days, with its tea partiers and Second Amendment obsessions and anti-intellectualism, that I start to think my four heros were all eccentric outsiders, hardly American at all, and the real America is something utterly foreign to me and fairly repugnant. It’s dubious to say that Cage was to Ives what Thoreau was to Emerson, but it certainly seems that Ives was to Emerson what Cage was to Thoreau. Cage didn’t like to talk about Ives, which puzzles me; because Cage’s close friend Lou Harrison did yeoman service as Ives’s copyist-conductor-assistant, and because Ives’s comment on Thoreau seems so perfectly Cagean: “Thoreau was a great musician, not because he played the flute, but because he did not have to go to Boston to hear ‘the symphony.’†(Cage didn’t care for Emerson, either.) I identify more strongly with the Emerson-Ives side of the equation, the Thoreau-Cage side being a little ascetic for my taste. Which is also odd, because I’m also a minimalist, and Thoreau is more minimalist than Emerson.

But Thoreau is easier to marinate oneself in. Since I was in Boston over the weekend, I stopped at Walden Pond (only 16 miles away, Thoreau used to walk it) and tromped around it through the deep snow. I sat on a hillside and even made an ambient recording, my own Walden 4’33†extended to 18 minutes, to bring home and meditate to. That gave me some strong musical images as well, even though the woods were so still that, except for the occasional plane and the lonely train whistle that went by, it was about as quiet as Cage’s anechoic chamber. (Sorry the photo’s not Walden, but I didn’t take my camera.) I rarely teach verbal texts in my classes, but we’ll be reading Emerson and Thoreau (as well as Hawthorne and Bronson Alcott) for my Ives course, so the feeling of getting back to my roots will only intensify in coming months.

Composing has been going slowly because in addition to the Silence foreword I also have the following writing gigs for this month and next:

* finish the Ashley book (done)

* a foreword to a new edition of Perfect Lives

* liner notes for Meredith Monk

* an article on Julius Eastman for a book about him

* a paper on postminimalism for the Ashgate Companion to Minimalist Music, of which I am co-editor, and

* updates for 18 Grove Dictionary bios, of which I’ve completed five.

I’m determined to spend my summer composing, so I hope American music can get by without me for three months.

Enthralled Them Throughout

My new string quartet The Light Summer Land got a nice, even generous review in the Boston Musical Intelligencer, as did the quartets by Thomas L. Read and Arnold Rosner. I think the piece needs a little revision. But I’ll post the recording when I get it, as well as what I learned about string quartets on my maiden voyage with one.

Finally Catching Up to MTV

Â

Â

The Relache ensemble conceived the really brilliant idea of getting a grant to commission a video piece to accompany my suite The Planets when they tour it. So I approached John Sanborn of Perfect Lives fame, thinking he was probably way out of my league, and to my surprise and gratification he leaped at the chance. Now he’s finished Venus and Mars, and they are absolutely magnificent: dancers, galaxies, poetry, astrological symbolism, paintings, planetary landscapes, labyrinths in whack, a whirling universe of imagery. So what Relache will do is tour the piece live in the fall with these wonderful video portraits projected on a screen behind them. And I am rather astonished at how quickly the music goes by while you’ve got something to watch. For this purpose I could have made the piece 150 minutes instead of 75. Still, with pauses it will be an evening-length multimedia show (and hopefully, some day, a DVD).Â

Now I’m off to Boston to hear my string quartet The Light Summer Land, at Harvard’s Memorial Church, 8:30 tonight.

Steven Bodner, 1975-2011

I couldn’t attend the performance of two of my Planets at Williams College Saturday because there was a snowstorm, and the roads leading from the Hudson Valley into northwest Massachusetts are slow two-lane roads up and down mountains behind trucks, uncomfortable driving even in sunshine. So I e-mailed Steven Bodner, the ensemble director, to say I wouldn’t make it, and he e-mailed back that he wouldn’t be there either because of a bad flu. And now Eve Beglarian informs me he died Monday night! I’m absolutely shocked. Steven was a vital, energetic, supremely talented conductor who had great rapport with his students and a creative, progressive approach to programming. He got in touch with me about performing my piano concerto Sunken City, and ably conducted the American premiere; then at my recommendation he was called to Bard on a kind of emergency basis to lead a performance of Feldman’s Rothko Chapel, which he executed beautifully. He was a real up-and-coming conductor, whom I saw potentially playing a national role on the new-music scene. What an inexplicable loss.

I couldn’t attend the performance of two of my Planets at Williams College Saturday because there was a snowstorm, and the roads leading from the Hudson Valley into northwest Massachusetts are slow two-lane roads up and down mountains behind trucks, uncomfortable driving even in sunshine. So I e-mailed Steven Bodner, the ensemble director, to say I wouldn’t make it, and he e-mailed back that he wouldn’t be there either because of a bad flu. And now Eve Beglarian informs me he died Monday night! I’m absolutely shocked. Steven was a vital, energetic, supremely talented conductor who had great rapport with his students and a creative, progressive approach to programming. He got in touch with me about performing my piano concerto Sunken City, and ably conducted the American premiere; then at my recommendation he was called to Bard on a kind of emergency basis to lead a performance of Feldman’s Rothko Chapel, which he executed beautifully. He was a real up-and-coming conductor, whom I saw potentially playing a national role on the new-music scene. What an inexplicable loss.

Sunken City is a tremendously difficult piece rhythm-wise, with constant changes in the first movement among meters like 17/16 and 11/8; and many of the students in Steven’s ensemble weren’t even music majors. When I asked him how he pulled it off with such precision, he said, “I never let them know it was difficult.”

Ha Ha, Made You Read

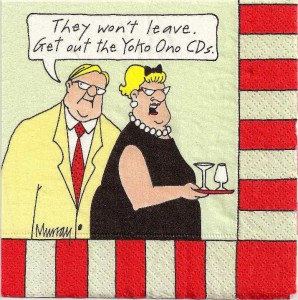

Quite a few years ago I found a packet of cocktail napkins with the image pictured below in a little house furnishings store in McKinney, Texas, where my mom lives. I had had some contact with Yoko Ono at the time, and had garnered quite a collection of her CDs, and it seemed like a hilarious idea to save these for just the right party, and hand them out to guests. It didn’t occur to me at the time that I don’t have any friends, and so parties aren’t a very regular event in my life, and so years later here they are, still in the original package. So what do I do with things that I can’t find any other use for? Post ’em on my blog.

It’s also an excuse to call attention to my new blog format, which came down from headquarters last week, and which puts a thumbnail of whatever image is in the post on the front page excerpt. Arts Journal Grand Vizier Douglas McLennan tells me that readers are five times as likely to click on a post if there’s an image attached. God, you guys are cheap. Like Pavlov’s dogs. I don’t take well to change except when I initiate it myself – I am given to impulsive total makeovers – but I’m glad one person has already found the new format friendlier. I’m going to miss the front-page differentiation among the sizes of the articles. I never liked the teaser-and-after-the-jump format. I’m proud to be one of the world’s most long-winded music bloggers, and when I post a 4500-word entry, I want the reader to glance down his screen at this Burj Khalifa of print and wax vertiginous. Only serious readers need apply. (It’s funny, I’m very populist about my music and completely elitist about my blog.) I have two kinds of posts, pretty much – brief comments and epic poems, and I’d prefer to have the distinction right out there, instead of a surprise. Oh well. Comments are a little easier to handle on WordPress, the software we switched to, and images certainly upload faster. We’ll see how it works out. In any case, at least I know how to make you click, you suggestible lab rats.

Language-Spinners and Image-Cutters

During the semester I rain forth repertoire on my students, and sometimes when I get a free moment I just obsessively need to hear something I don’t already know. A Christmas DVD of Cavalli’s Calisto, one of my favorite operas, put me in an early Baroque mood, so I digitized all my Cavalli and Carissimi and Cesti vinyl, and remembered that I had always wanted to be more familiar with Biber, so I discovered his two requiems, which are supremely beautiful, especially the F minor. Then I saw a reference to Nicolas Medtner, literally just his name, and suddenly realized that I had never satisfied my curiosity about the Medtner piano sonatas. They have a cult following, and since I’ve always hoped my music would acquire a cult following, some band of intrepid enthusiasts to run around claiming that it’s not as bad as people think, I’m always on the lookout for models in that respect. So IMSLP.org has all the Medtner Sonata scores, and I could listen to them through the Naxos web site that Bard subscribes to, and I approached them the Scorpionic way I approach everything: I listened to all 14 of them back-to-back.

And I love them. I’m a sucker for meandering chromatic piano music anyway. Sometimes I think that as the son of a piano teacher I just find the sound of the instrument comforting, it almost doesn’t matter what you play on it. But I’ve always considered the Scriabin sonatas a little formally timid, and Medtner leaps in where Scriabin fears to tread. His textural details are often quite original, and in his “Night Wind” Sonata Op. 25/2 he has an entire movement in a natural-sounding 15/8 meter, cleverly inflected with hemiolas:

Â

Â

It’s great stuff, and I am now officially a card-carrying Medtner cultist. He may suddenly be my favorite Russian ever besides Stravinsky, and I hardly think of Stravinsky as Russian.

At the same time, I can see why Medtner has never gone mainstream, and never will. Except for the rather immature Op. 5, stylistically, those sonatas are much the same. Supposing I want to hear (or play) Medtner, which sonata do I choose? Hearing them all in four and a half hours, they could just as well have been one piece; which movement went with which sonata didn’t make much audible difference (and I’ve given several of them repeat listenings, with and without scores, and played through movements). There are lots of wonderful harmonic sequences, broken by reappearances of dotted-rhythm motifs. Some are stormier than others, some are multi-movement, some long, some short, but it’s a 280-minute mass of solid Medtner. The music doesn’t breathe much, and no real adagio ever appears. He had a tremendously sophisticated language in which he could sit down any time he wanted and write more Medtner. But with a few exceptions (mostly the early Op. 11 trio of sonatas and the late Sonata-Idylle, I think, and the “Night Wind” has some distinctive material), he didn’t have “an idea” for each sonata which differentiated it sharply from the last sonata. Like Bruckner and his symphonies, Medtner pretty much had one sonata in him and wrote it 14 times, and I don’t mean to disparage either composer in the least, for I yield to no one in my Bruckner worship. But it does mean, I think, that the listener’s attention is drawn more toward Medtner as a style than toward, say, the Sonata Manicciosa as a discrete piece.Â

Let’s go back to this blog’s default composer Feldman for a moment. Feldman had it all. He had an instantly recognizable style. At the same time, think about how distinct three of his orchestra pieces are from each other: Turfan Fragments, Coptic Light, For Samuel Beckett. No one who knows those pieces would confuse them on a drop-the-needle test. (Kids, dropping the phonograph needle on a record was what we used to do with vinyl, to enliven our cave parties.) Within his well-defined idiom, Feldman could create a striking image for each piece that set it apart from the rest of his output. Or to take a competitor with whom Medtner would have been all too familiar, Beethoven’s Sonatas do not dissolve into Beethoven-language. I could be in a mood to hear Op. 111, or Op. 90, in which Op. 53 or Op. 57 would just not fill the bill. It’s not true of every Beethoven’s sonata, but the best of them each define a small (or large) world.Â

It is a trap that some composers fall into (and there are so many of them, aren’t there?, traps, I mean) that they can develop a language and then sit around writing pieces in that language. A piece is not simply nine yards of a given composer’s language snipped off from the rest – it’s a thing with its own bounds and unity and personality. Years ago Boulez made some statement about having “perfected his language,” and I wrote an article with the sub-headline, “Pierre Boulez perfects his language – but does he have anything to say?” Music and language are analogous in various respects, and the fallacy that music is only a language is so seductive that it sucks certain people in, letting them forget the fact that much of what we remember and most savor in music are specific sonic images. The composer may have a big impact – but his or her pieces may be individually forgettable.Â

And, from whatever congenital impulse that’s hardwired into my amygdala, that’s a trap I am more averse to than some of the others. I am driven to make each piece as individual as possible. I hate repeating myself. I have a big bag of quirks, but I don’t think I possess “a language.” Every major piece I start seems to require a new way of composing from me, which is why I often spin my wheels for awhile when I first get started. I probably overemphasize with my students that they think about what “the idea of the piece” is. It could be called a more “objective” kind of composing, because the entire emphasis is on the object, and I am always willing to abnegate any usual composing tendencies I think of as mine to achieve what the piece needs. And perhaps, avoiding that Scylla, I fall prey to the Charybdis of not having an individual enough composer profile.Â

There are historic composers, some among my favorites, like me in this respect. Nancarrow rarely repeated anything. A kind of “Nancarrow style” is imposed on our perception of him by the fact that 51 of his pieces were for the same peculiar instrument, but in my book on him I list 26 good ideas that he used once and never touched again. He could be tonal or atonal, jazzy or abstract, chaotic or elegant, and any permutation of those. Or to take a more directly apposite contrast to Medtner, Ferruccio Busoni is one of the most piece-oriented composers ever. If you’ve heard of him at all, you know he has a big romantic piano concerto, and some sonatinas, but the concerto is in a complete different idiom from the sonatinas, and the sonatinas hardly match well enough to constitute a set (one atonal, one Bach-like, one based on Carmen for gosh sake), and the string quartets and operas are something else altogether. Busoni is one of my very favorite composers, and even I can’t make the Romanto-Moderno-Neoclasso jigsaw puzzle of his output fit into a picture. Each piece has an impact, but Busoni himself has a fuzzy reputation.

Of course, the preferable thing would to be like Beethoven or Feldman or Stravinsky, and write memorable pieces within your own distinctive style. But it doesn’t seem that we get to choose where we fall along this continuum, whether it is decided for us at birth by the structure of our neural system or imposed upon us from without by the opportunities we’re given. Still, who says that that coveted middle position will make you everyone’s favorite composer? Some of us are drawn to artists whose strengths are less obvious. If I’m offered the position as my generation’s Busoni, I’ll leap at the chance. And I suppose what I’m saying is that there are advantages on both sides. I can listen to Steve Reich and say, “Boy, I wish my music had that clear a profile”; but I can also listen to Medtner – and love every note of it – and still say, “Boy, I’m glad my pieces don’t all blend together.”

Space Is the Place

After a dry fall I have two big performances coming up within a week of each other. Steve Bodner, dynamic young conductor who gave the American premiere of my Sunken City, has his annual I/O Festival coming up Jan. 6-8 at Williams College in northwestern Massachusetts. The Saturday afternoon concert of Steve’s Opus Zero ensemble, 1:00 on Jan. 8, is an all-astrology concert – Stockhausen’s Tierkreis, “Neptune” and “Venus” from my suite The Planets, and three pieces by Sun Ra, including Saturn (1958) and Space Is the Place (1974). I think I heard Sun Ra’s group do that second one live in Chicago way back when. Me, Stockhausen, and Sun Ra – there’s the historical niche I’ve been waiting all my life for. I will definitely have to wear my pyramid hat.

Gambling Tips for Smart Performers

I want to draw attention to Allan Kozinn’s thinkpiece about the vagaries of new-music performance in yesterday’s Times (tried to post then, got caught in a holding pattern involving site changes), which is pitch-perfect in talking about why, how, and with what expectations performers should undertake the performance of newly composed music. I would add one thing. I would urge new-music performers to look for composers to commission outside the usual roster of composers on the regular chamber-music or orchestra circuit. Many of the best composers are better at composing than they are at networking, and are devoted enough to get their music out that they’ll do it by themselves if that’s what they’re reduced to. That means they may work in some electronic or self-produced idiom which you mistakenly think is all they’re interested in, or talented for. You may think they’re not really chamber music composers, or couldn’t write for piano trio, or something, and you might often be entirely wrong. For instance, no classical chamber group would commission Glenn Branca, right?, since he only writes for electric guitar ensembles – except that Glenn’s string quartet is one of his best works, and one of the most beautiful essays in that genre of the last 25 years. (No recording of it exists that I know of, unfortunately, but I once heard it live and reviewed it.) And Carl Stone is an electronic composer, he wouldn’t know how to write an acoustic piece – except that the piano pieces Sarah Cahill has commissioned from him are absolutely charming.

Kozinn is exactly right that a new piece needs to get played publicly and played well, and considered for awhile, before we can decide whether it’s a keeper. Similarly, composers who show brilliant imagination in one medium need opportunities to branch out into others, and shouldn’t be bypassed based on some superficial canard about “proven track record” in a given medium. You might occasionally draw a clunker, just as you can with any Pulitzer prize winner, and it’s a risk you have to take. But a composer who’s spent his life in solo performance or electronics because it was the only route available might turn out to have a couple of gorgeous string quartets inside him (Ingram Marshall is a classic example).

In an unrelated bit of news, I note that Postclassic remains number 6 on the ranking of classical music blogs. I’ve been passed up by Nico Muhly as the top single-composer blog. Frankly, I’ve done so much to reduce and alienate my readership that I’m astonished to still be in the running at all. I rather think of this blog as a book I wrote awhile back that I’m still adding the occasional footnote to – that, and also I’ve been incredibly overcommitted lately, and am turning down writing jobs left and right. But despite all my most cantankerous efforts, there I remain. Strange indeed.

Â