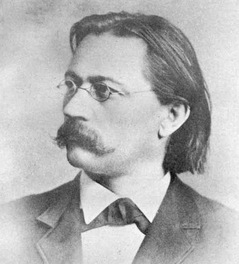

I’ve always had a fascination with canons, even long before I wrote a book about a composer (Nancarrow) whose major works were mostly canons. In the late 1980s, when I was in the habit of lecturing on the history of Chicago’s new-music scene at the School of the Art Institute and other places, I ran across, in a Chicago used bookstore, a little book called Canonical Studies, by Bernhard Ziehn (1845-1912, pictured). I recognized the name. Ziehn was one of two German composer-theorists who were living in Chicago when Ferruccio Busoni toured through. Busoni was trying to solve the puzzle of how the four fugue subjects

I’ve always had a fascination with canons, even long before I wrote a book about a composer (Nancarrow) whose major works were mostly canons. In the late 1980s, when I was in the habit of lecturing on the history of Chicago’s new-music scene at the School of the Art Institute and other places, I ran across, in a Chicago used bookstore, a little book called Canonical Studies, by Bernhard Ziehn (1845-1912, pictured). I recognized the name. Ziehn was one of two German composer-theorists who were living in Chicago when Ferruccio Busoni toured through. Busoni was trying to solve the puzzle of how the four fugue subjects

fit together in the unfinished fugue from Bach’s The Art of Fugue, and Ziehn solved it for him, enabling Busoni to write his Fantasia Contrappuntistica, which has long been one of my very favorite works in the world. His tour over, Busoni wrote an article about Ziehn and his colleague Wilhelm Middelschulte, titled “The Gothics of Chicago,” by which term he meant that they were masters and fanatics in the ancient art of counterpoint. Ziehn and Middelschulte taught a lot of the early Chicago composers, including John J. Becker (one of the “American Five”), whose widow I knew in Evanston. So I had multiple connections to Ziehn, and snapped the book up at once.

All but forgotten today (there’s a brief entry about him on German Wikipedia, none in the English one, and the second reference that came up on Google was a page of my own), Ziehn was ahead of his time. Books he published in the 1880s anticipated and classified chords (such as those based on the whole-tone scale) that the impressionists and Schoenberg would use considerably later. In the intro to Canonical Studies, Ziehn writes,

A canon is by definition strict. Our greatest authorities assert “strict” canons can be carried out in the Octave of Prime only. The examples given in this book demonstrate that real canons are possible in any interval…

And he gives examples of chord progressions that modulate to every possible interval away from the tonic, showing how one can continue repeating those progressions in ever-moving transposition to write canons not based on the octave or unison.

I was intrigued, and in 1987 wrote what I call a “spiral canon” as the third movement of my violin piece Cyclic Aphorisms, a canon at the major second. Then, more ambitiously, in 1990 I wrote Chicago Spiral, a nine-part triple canon also at the major 2nd, putting a postminimalist spin on Ziehn’s idea. A canon is easy to perceive as such at the unison, octave, or even fifth; it’s more

challenging at a more distantly related interval. A canon is also easier to process aurally if the beat-interval of rhythmic imitation is something symmetrical like 4 or 8 beats, more difficult if it’s 13 or 31. One thing I’ve realized is central to my music is that I love to fuse the simple with the incommensurable, making the listener think it ought to be easy to figure out what’s going on, but keeping it just out of reach. My Ziehn-inspired spiral canons ought to be simple to figure out by ear – they’re only canons, after all – but the complexity of the imitation intervals, both rhythm and pitch, keep the ear, I think, from ever quite settling into them. I also use the technique as kind of a postminimalist gradual-texture-metamorphosis generator, which is a little beyond what old Ziehn had in mind, I imagine. Paradoxically, the longer the rhythmic interval of imitation, the less gradual the changes can be made.

And now in recent months I’ve written two more such canons, Hudson Spiral and Concord Spiral, both for string quartet. Along with the middle section of my orchestra piece The Disappearance of All Holy Things from this Once So Promising World, I’ve produced five spiral canons altogether, at the following rhythmic and pitch intervals:

Cyclic Aphorism 3: 5 beats, major 2nd ascending

Chicago Spiral: 7 beats, major 2nd descending

Disappearance: 17 beats, minor 3rd descending

Hudson Spiral: 83 beats, major 6th ascending

Concord Spiral: 19 beats, minor 7th descending

The major 6th and minor 7th are the optimal intervals for a string quartet canon; using a major 6th, the cello can play down to its low E-flat (echoed by the viola’s low C string and second violin’s low A), and the first violin can play down to the F# above middle C, whereas with the 7th the cello can descend to D and the first violin only to A-flat in the treble clef. Concord Spiral generated some nice passages of what sounds like tonal Webern:

The scores are on my web site if you’re interested, and no performances are yet forthcoming. Spiral canons and Snake Dances are the two personal genres I feel I’ve invented for myself, along with my more generic tuning studies and Disklavier studies. And I hope Ziehn would have been happy to know that, 98 years after his death, his idea is still out there making the rounds.