I’m rather astonished by the convergence of major performances I suddenly have in the next several weeks, some of which I only just now learned of:

Archives for January 2010

Getting Off the Assembly Line

Your generous responses to my little outburst about being tired of blogging certainly made it clear what most useful direction this blog can continue to go in. I may be out of ideas I haven’t expounded, but my file cabinets and hard drives are still chockablock with music that’s not in general circulation, and listeners are eager to have their experience widened. If I do no more than satisfy that longing, I will have felt that my trip to this planet was not in vain. If I become in the process sort of the Dick Cavett of avant-garde music, so be it.

One of the themes of my life has become something I never expected. I’ve based some large part of my career around documenting recent music not adequately represented by its score notation. It started with Nancarrow. His scores contain all of his notes, of course, but many of them, especially the late player piano studies, don’t provide as much explicit rhythmic notation as is actually inherent. After some brief acquaintance with Nancarrow’s music I formed a theory that, even when it looked like he was rather intuitively splashing notes onto the page, there was always some underlying tempo and even isorhythm to which everything referred. Some painstaking analysis with a little plastic millimeter ruler quickly bore me out, and I found further confirmation when I was able to consult his punching scores – from which he made his final scores, but omitted the messy tempo-grid information.

Since then I have stumbled upon a wealth of music whose score notation, if it exists at all, doesn’t adequately represent it. I reconstructed Dennis Johnson’s November from the recording and score fragments, and have spent time transcribing improvisations by Harold Budd, Elodie Lauten, and others. I’ve reconstructed some of Mikel Rouse’s ensemble music from parts and mathematical models. Harry Partch’s music is indecipherable as to pitch unless you know the various tablatures of his instruments, and, in the case of his Kitharas, I’m told that you can’t figure out the music without knowing how to play the instrument.

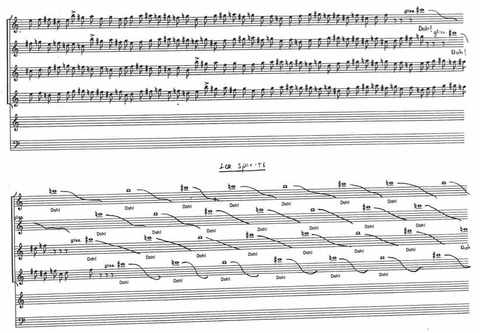

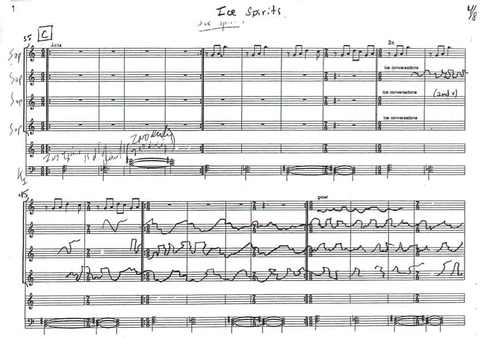

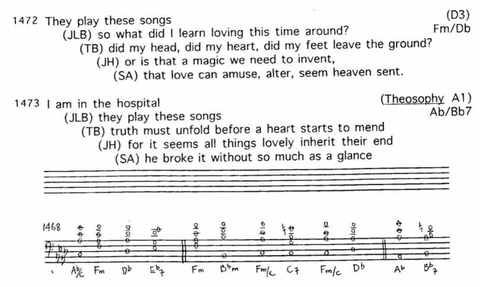

Lately I’ve finally been studying a rather sketchy 392-page score to Meredith Monk’s 1991 opera Atlas that she was kind enough to give me years ago. Meredith refuses to have her singers learn music from notation because it detracts from a lively performance; she prefers to sing their lines and have them sing them back, as in Indian music. The Atlas score pretty much contains the instrumental parts verbatim, but some of the vocal parts are left blank on the page, indicating that they were to be developed in rehearsal. Scores to two of the most beautiful sections, “Choosing Companions” and “Agricultural Community,” contain no vocal parts at all. The “Ice Demons” music, when compared with the recording, shows how precise some of her notation is, how free it is in other places, and how free the singers were to ignore it in either case:

The whole score is a fascinating document of Meredith’s working method. Occasional passages are blanked out, omitted in rehearsal, and where the vocal rhythms (heard here) are exactly notated, the actual performance is often much freer:

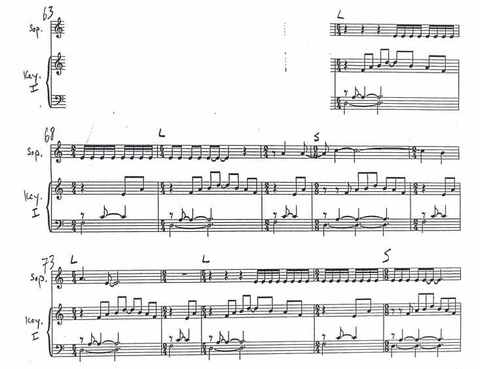

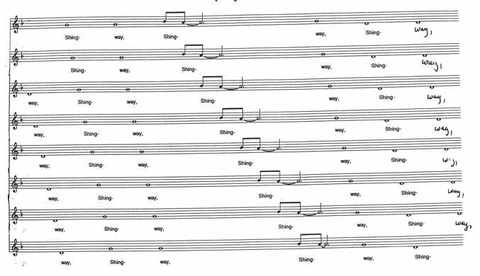

It’s difficult to imagine improving on the unconventional notation of the “Shing Way” section, in which the singers sit in a circle and pass each pitch or figure linearly from one to another (recording here):

I don’t know whether, since 1991, Meredith has made a nicer, more complete score of Atlas, but why should she? This was adequate for a series of stunning performances, and it represents a starting point for the piece, not an end product in itself. Some musicologist could certainly prepare a nice final score using this and the recording as guides, but this one tells more about Meredith’s working method than an engraved Universal Urtext ever could.

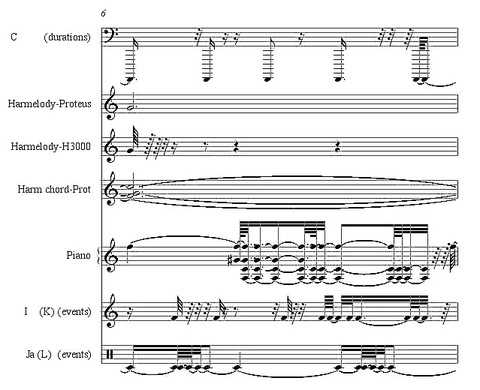

The lack of scores is a big issue for studying Robert Ashley’s music as well; or rather, the discrepancy between his spare working scores, his “production notebooks” as he calls them, and the information overload on the recordings. Years ago when I analyzed Improvement: Don Leaves Linda with a class, Bob kindly gave me the complete MIDI files for the piece, but correctly warned me that they wouldn’t be much help. They were used to trigger events in primitve 1980s software that no current computer still supports, and it’s only here and there that one finds telling correspondences between the MIDI and the recording. Translated to notation, the MIDI files look something like this:

It’s possible that some tracks triggered only markers heard by the performers through headphones, and not by the audience.

More typically, Ashley’s actual scores contain the libretto marked out in numbered lines, surrounded by harmonic or melodic notations where needed, like this page from Dust:

Ashley takes on the problem of how someone else could perform his operas in an article called “Style and Technique: Performance Practice,” which is collected with his other writings in a dazzlingly huge and mind-challenging new collection of his writings from MusikTexte titled Outside of Time: Ideas about Music, which I will surely be writing more about later. “The solution,” he writes,

is to get all of the operas recorded in a finished form in the most recent format (now, compact discs). Anybody who wanted to produce one of the operas could work from the compact disc, which represents the way the opera is to be performed and how it is supposed to sound. Except for the rhythmic treatment of the words, which remains a notated constant, there is no score from which to make the orchestra. As I have said, the studio production notes for any opera will make little sense in the future, even if I could decipher them now, because they refer to instruments that will be long gone.Â

He talks about a student writing a dissertation on Perfect Lives, to whom he had to explain that a score did not exist.

…about two months later I got in the mail a very accurately transcribed orchestration of the first episode of Perfect Lives, “The Park.”

This is how it should be. The person listened. This is how jazz musicians learn jazz. This is how most of the people in the world learn the music they play. [p. 190]

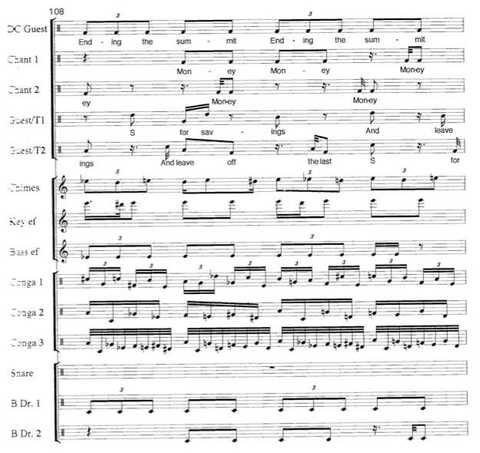

Like Ashley, Mikel Rouse has a ton of MIDI information in his scores that can’t be deciphered without access to his hardware setup, and can only be documented by reference to the recording. The “chromaticism” in his unpitched percussion parts in this measure from Dennis Cleveland is a dead giveaway:

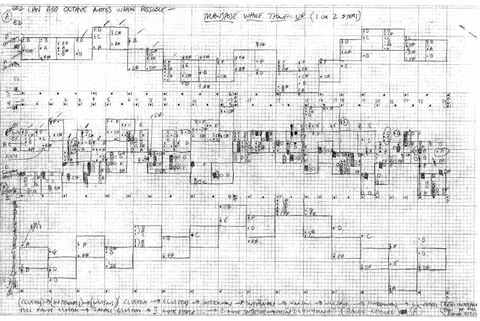

I also have a pile of one- or two-page scores by David First that I hope to get to someday, marked with little more than noteheads and plus-or-minus-cent numbers. The following page seems to comprise the 15-minute entirety of his piece Distance Receives Permission to Enter from the album Resolver:

You can listen along and follow the whole piece here. I doubt there’s much danger of someone taking the score and arranging a performance independently.

Finally, here’s an intriguing passage, with Totalist rhythms, from Glenn Branca’s Symphony No. 6 for electric guitars, back from his pre-musical-notation days:

In a way there’s a mirror image here, within academic discourse, to 12-tone music. Twelve-tone music and its related forms inspired an immense music-theoretical literature devoted to explaining how the music, opaque as it often is to the ear, is made, and by extension how it is to be heard. Minimalism and its related forms are likewise inspiring a new literature in musicology, for scholars simply trying to document what the music consists of. Famous pieces can be reconstructed from recordings. Partch’s scores get published in just-intonation-notation transcriptions. Even Steve Reich’s celebrated Music for 18 Musicians was apparently notated so idiosyncratically that younger composer Marc Mellits had to do considerable work on the score to make it publishable by Boosey and Hawkes.

The music is worth analyzing. But it is not the composer’s responsibility to make it available for analysis – it is his or her responsibility to successfully bring it to performance. If more is needed for teaching purposes, there are musicologists. As Cage would have added: use them.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Of course, scores like these pose a pedagogical problem. They depart from the universal paradigm for what a score is: a linear continuity on bound paper which contains all the information needed to replicate the piece in performance. The central core of the composition teacher’s job is to teach a student how to write self-contained music for strangers to play. Students have often told me the goal as other teachers have stated it to them: your score should be so detailed and self-explanatory that you can mail it to an ensemble in Japan who are unfamiliar with your music, and they’ll be able to send you back an accurate recording. Of course, I find this ideal illusory at best. I’ve sent pretty clear scores to friends who know my work well, and shown up for rehearsal to find energy levels and tempos all wrong, even with dynamics and metronome markings quite explicit. The truth is, traditional musical notation is at best never an entirely efficient transmitter of an imagined musical sound object. The participation of the composer is omitted at everyone’s peril.

The other truth is, music is not necessarily an imagined sound object (though in academia it is often assumed to be only that). Often it is the result of a process, and emerges only in rehearsal. And the intense conformity to expectation involved in learning to make a detailed conventional classical score is a great reiner-in of imagination and individuality. I see my students wrestle, touchingly, with this problem every year. Some of them are eager to write for orchestra and other conventional classical ensembles, and they want to be taught to notate by the book. Others are used to working in rock bands and alone and with friends, and they have effects they want to try out, experiments they want to conduct in rehearsal, parts that they want to leave to improvisation, rhythmic effects that just won’t conform to a notated meter. Some of them come up with pretty idiosyncratic notations, but they play the pieces and get what they want. Then they decide that they can’t resist that opportunity to write for orchestra for their senior project, and I have to explain at great length what they can expect to achieve with a conventional orchestra in 20 minutes’ rehearsal. They want to put radios in the orchestra, have the players shake boxes of metal debris, improvise with the orchestras at different tempos under two conductors, and so on. (We did manage an amplified toy piano in the orchestra one year.) But the classical performance paradigm is an assembly line, and much of composition pedagogy is involved with teaching them, and limiting them to, what can be achieved by players basically sight-reading what’s been plopped on their music stands. I never push – but some of them decide not to curtail their individuality for the assembly line, and I applaud them after they make the decision. It takes courage.

As one disaffected young composer recently wrote to me about his crucifixion in the academic milieu, “There is no career success outside this horseshit, and no artistic success within it.” That’s pretty close to the truth. But in the long run Ashley and Monk and Rouse have managed pretty enviable artistic lives by working outside the system. It takes a kind of relentless heroism.

So you don’t like the words Uptown and Downtown: fine. But if you deny the existence of this division in order to erase from your consciousness the fact that some of the most creative and original of recent composers have gone outside the classical paradigm to escape its stultifying limitations, then you delude yourself. Our new music suffers more than anything, I think, from a relentless conformism pushed on young composers in the name of “professionalism,” and conformity does not excite audiences. Perhaps we can begin by de-fetishizing the printed score and admitting that it is only a tool, and not always a complete or even necessary tool, that it can sometimes be thrown away once the music exists. Making scores like the above examples available as models for how to go outside the norm, and analyzing the music that goes with them as best we can, may be a start.

But I Thought My Office Was THIS Way!

I’ll tell you one perennial feature of academic life that I would gladly forgo is the inevitable beginning-of-semester anxiety dream. This time Bard was an urban campus high in the hills, clotted with fast-food courts, and a new music building had been built on the tallest hill. There was a long iron staircase leading to it, but it wasn’t the obvious staircase; you had to go underneath and around somewhere. I swear I remembered the layout of the new building from a previous dream, a semester or two ago. My first attempt to get there having circuitously led only to a boat wharf, I got on a huge red shuttle bus, like a metropolitan tour bus, and rode around looking for the right entrance. Meanwhile, my class was to have started 20 minutes ago, and since I knew the students and had already talked to them I knew they’d wait for me, but I hadn’t made out a syllabus nor Xeroxed any handouts. At least this time I was teaching music theory instead of French or something, and it was my regular school instead of a new one I’d just been hired at, but the lack of handouts is a constant. In my dreams I never have any handouts, though in waking life I could teach the entire music curriculum of the Sorbonne from the contents of my external hard drive.Â

BAM? Damn! Thank You, Mark

During my years at the Voice I would periodically opine that Brooklyn Academy of Music was the best place to perform in the country because they had the savviest, most interested audience one could ever wish for. Ever since 1981, when I saw Satyagraha there while coincidentally sitting in the balcony next to Steve Reich (to whom I didn’t reveal that I recognized him), I’ve considered it the Taj Mahal of the avant-garde. I never imagined that I was hip enough to ever have my music played there. But this afternoon a colleague mentioned having seen my name in the BAM brochure, and sure enough, the Mark Morris Dance Group is performing Mark’s dance Looky, with five of my Disklavier pieces as accompaniment, at BAM on February 23, 25, 26, and 27. (The photo on the BAM page is from an earlier performance of the piece.) And the only other music on the program is Erik Satie’s Socrate, the masterpiece of one of my most kindred spirits. I’ve never been so impressed with myself. I’ve been trying to think of a gig I’d be more honored by, and I can’t think of one.

Land of the Forgotten Composers

Thursday I got a request from a site called Classical Lost and Found asking me to link to their site in return for their linking to my site. I don’t like doing this. First, if I had taken every request I’ve gotten like this, my blog roll would be a mile long. Secondly, the last thing I need is a bunch of classical-music fans sticking their nose into my blog and clutching their pearls over my references to whale vaginas and uninflected dynamics. After all the work I’ve done to try to reduce my readership, it might put me back to square one. However, CLOFO’s (as they abbreviate themselves) motto is “Forgotten Music by Great Composers and Great Music by Forgotten Composers,” which could just about be the title of my autobiography as a writer. Sure enough, I clicked, and within seconds I had found a recording of Roy Harris’s Eleventh Symphony, which I hadn’t realized was available. So I figure some of my readers here might appreciate knowing about the site.

Aiming My File Cabinets into the Right Student’s Ears

Kyle, please keep blogging regularly. Your metametrics posts literally changed my life when I was starting my undergrad. I am now waiting to hear from grad schools after sending them applications and writing samples covered in the names Branca, Chatham, and Gordon.

This comment to my last post sticks acupuncture-like into my reasons for blogging or not blogging, my attitude about teaching, and a lot of other aspects of my life. I never press minimalism, postminimalism, or totalism on my students. Some of my composition students are very ambitious, and want to go to grad school. I know that a knowledge of, let alone strong interest in, Partch, Branca, Diamanda Galas, Glass, Young, Mikel Rouse, Ashley, Art Jarvinen, and all these other nutcases I’m fascinated by – what I consider the great music of my time – will not be assets to an academic composing career. I know my students should be able to analyze Stravinsky, Stockhausen, Nancarrow, Webern, and what academia considers the canon. I feel guilty even trying to interest them in the music I most believe in, because while it might excite them artistically, I know that the best composition careers go not to the most exciting composers, but to those who follow the academic/classical script. Of course, if they come to me interested in that music, I eagerly supply them with all they want. I have two file cabinets bursting with unpublished and self-published scores of “my kind of music.” A handful of students, mostly grad students from other schools, have come to me precisely for that, but not one has ever taken advantage of more than a fourth of what I could offer in that area. Consider:

A few years ago, a few students asked me for a tutorial on minimalism, which I happily provided. One of my colleagues, finding out, became incensed with me, and shouted, “See? You’re influencing them! You’re influencing them!” – as though I weren’t supposed to do that. But in fact, the student who led the tutorial request was the son of a woman whose favorite composer was Steve Reich. I try not to influence my students toward my own aesthetic direction because I know it won’t help them career-wise.

I apply frequently for senior composition, theory, and history jobs, but I almost never get interviewed. My publication record is superb, I have excellent references from friends who chair departments at other schools, and my student satisfaction ratings are very high. I can only conclude that it is the content of my publications, my academically incorrect aesthetic position, that scares away other departments from considering me. Sure, I directed an international conference on minimalism – but minimalism remains a dirty word in academia. And why would I want to burden any of my students with the same disadvantages under which I labor?

And yet, aside from writing my music, which I secretly think is very good – one of my guilty pleasures – I think the most useful and fulfilling role I could play would be as a distribution channel for the commercially and academically unviable music I love. Nothing would give me greater pleasure than for someone to provide me with the money and wherewithal to scan those files cabinet’s worth of scores to create a Free Internet Library of Downtown Music, where students who have an interest in it, like Patrick above, could feast their eyes and ears on all this alternative music. But how could I do that in a world in which copyright difficulties won’t even allow me to write, “Creep into the vagina of a living,” etc., and in which even the word “Downtown” raises the hackles of the vast majority of musicians? As long as there was a Downtown scene in New York that provided an alternative career path for composers who don’t write the kind of music orchestras and those oh-so-precious classical musicians will program, there was a reason to continue this work. Incorrigible heretic that I am, I believe that there still is a Downtown scene: you’ll find it in organizations like Anti-Social Music and New Amsterdam Records, among others, in which young composers take the distribution and performance of their music into their own hands, which is virtually a definition of Downtown. But even the young composers involved today seem uninterested and unknowledgeable about the music I’ve spent my life immersed in. Downtown New York has always been that way: each new crowd comes in, and has little feeling of connection with the dominant crowd that preceded it. Bang on a Can shrugged off free improv, just as Zorn shrugged off minimalism. And I find myself working night and day for a musical generation that has been shrugged off Downtown, and of course doesn’t exist for academia or the classical music organizations.

Frankly, I’m 54, and I’m dog-tired of working as hard as I’ve worked all my life. But more accurately, I think I would be happy to continue doing the work if considerably more reward and acceptance came as a result. I’ve been on a big scanning spree during this winter break – mostly of scores I plan to teach in upcoming semesters, and largely because I save a ton of trees by projecting the music on a screen in class rather than Xeroxing it. But I also keep scanning scores of the postminimalist music I like to lecture on, and one score I scanned this week was Carolyn Yarnell’s The Same Sky, which I think is one of the most fantastic keyboard works anyone’s written in the last 20 years. I’ve made it available here before on mp3, and I do so again here, also with part of the score, which I think Carolyn will be rather complimented than annoyed by:

Kathleen Supové is the pianist. [UPDATE: By the way, notice that the sole dynamic marking is the mf at the beginning. The second dynamic marking is a pp on page 8. Welcome to postminimalism.] I hope to get time to analyze the piece sometime, so I’ll have more to say about it. What would be even more gratifying would be if I inspired some student to analyze it and send me the paper. I wish I could direct this activity specifically toward the younger musicians who would find it interesting, and not toward those who reflexively find it Not Serious. I rarely get to feel that such efforts are worth the amount of work I put into them. I seem more often penalized for my expertise than rewarded for it. But to the extent that this blog has a purpose, this is where I see it. It is not a very efficient medium, but it is almost the only medium I have, aside from the laborious producing of books.

As always, the number one and inviolable rule of this blog is, if you don’t like the music, I don’t want to hear from you, and will not publish your response. It would be unfair to Carolyn to get criticized on the internet as a result of my momentary appropriation of her work. If you don’t like the music, ask yourself why you think it’s important for the world to know you don’t. What good does an expression of your disapproval serve? None of the composers I champion is getting rich off their efforts; most of them are eking out extremely slim careers. They and I wield no power over others that needs be combatted. By criticizing, you merely add your voice to an enormously well-supported status quo that will thrive nicely without your reinforcement.

In other words, if I can figure out how to get this blog to more efficiently serve the grandest purpose I can imagine for it, without wasting energy on all the other stuff that serves no purpose at all (like defending the music and my terminology), I will gladly keep doing that. And if I figure out some other medium that would be more productive and rewarding, I will switch to that – even if it turns out to be something less public.

What Blogs Are Good For

1. I keep noticing that I’m repeating myself. I’ll write a blog entry and two days later notice I expressed the same idea in 2005, better.

2. I’m tired of being criticized, which is something that’s been an issue my entire life. In high school I was practicing Webern, Ruggles, and Rochberg, and was told by my classmates that I wasn’t as good a pianist as this kid who could play “Hava Nagila,” because he played music people liked. In my early years as a critic, the criticism made me sharpen my arguments and become more strictly evidence-based. Now it just makes me self-censor. For instance, the term “Downtown” just drives some people insane, and so I’ve learned a hundred ways to write about Downtown music here without using the word. But what fun is blogging if I have to self-censor – or else deal with blizzards of complaints?

3. I suspect the blog keeps people thinking of me as a critic. It makes sense that managers keep sending me press releases and artists keep fishing for articles, but I’m trying to discourage it, and I’m afraid the blog has the opposite effect. Critics write blogs, especially when their print medium goes under; composers don’t, or not often, and a composer’s blog is presumed to be read only by his music’s diehard fans, which would cut my readership down considerably. Putting my name in front of the public every week, as I’ve been doing since 1983, became a habit, as difficult to stop as any other habit. For years it was a way to keep my name in the air while I struggled to get my music out. But my music’s out now, at a level respectable enough for a former Downtowner, and I don’t want any more gushing feature-story requests from ensembles that wouldn’t consider giving me commissions. Yet I feel guilty writing about my own music here, because this started out as a critic’s blog, like I’m promoting my music under false pretences.

What I need, after six and a half years, is some kind of blog makeover, like Alex Ross has given his blog (though his content doesn’t seem to have changed as much as his format). I’m thinking about the things blogs are good for, and what they’re not so good for:

1. Gathering information: this is perhaps the most beneficial, for me, purpose of the blog. Sometimes I need information or perspective, as I recently did on the idea of teaching a 12-tone class, and everyone with any expertise to share is happy to write in. It’s like having 3,000 free consultants. I would miss it terribly if I quit.

2. Writing about teaching: wonderful. All we music theory or history professors are pretty much in the same boat, all of us run into the same problems, none of us have been specifically trained to do this, and we can all use whatever suggestions we can get.

3. Presenting musicological work: not so good. If I’m writing a book or scholarly article about something, it’s because I’m sitting here looking at and listening to materials you don’t have access to. Unless you are Keith Potter or Charlemagne Palestine or somebody, your insight into what I’m writing about is not as good as mine. Everyone has a right to his or her opinion of my music; only a handful of people have a right to their opinion of my scholarship, and those people will be consulted by the peer-reviewed publications I write for. A blog is a democratic format, and scholarship is not a democratic activity. I’ve come to think that the presentation of incomplete musicological research in blog format has a poor return. One nice thing about writing a book is, anyone who wants to refute you’ll have to write his own damn book to do it, not just fire off a note on his laptop.

4. Information about my music: feels self-serving. Of course it’s a godsend being able to provide my own publicity for upcoming concerts, and it would be difficult to give that up. Essays about my music, though, should probably go on my web site, where people interested in my music can go to look for them, and I’ve been adding material there lately as a substitute for blogging. I even suspect that my presence in the blogosphere inhibits my music being discussed there. You’re either a subject of the conversation or one of the conversers, and no one has demonstrated yet, I think, that you can be both.

5. Opinions: mine are notoriously unconventional, and I get tired of defending them. Some days I wish I’d kept my big mouth shut all those years. As for trivial opinions like my favorite movies and beers and such, I respectfully disagree with the blogging community that anyone should care.

6. Various goings-on in the music world: of course this is what blogs are for, but it requires a tremendous administrative investment, and, frankly, more curiosity about the outer world than I possess. For decades I kept track of concerts, records, books, and I just don’t anymore, especially now that the music of the Downtown scene I was involved in gets so little attention. And if you write praising one composer’s new CD, 32 other composers get the idea that you’ll write about their CD too, and the correspondence alone takes hours a week. For decades I was a willing and active cog in the capitalist publicity machine, and you’re either in or out of that machine; there’s no hanging around the periphery.

And so I’m left with information requests, observations about teaching music, and notices of my upcoming concerts. Maybe I’ll get inspired to start a new direction. But for now I’m composing daily, and I think getting out of the habit of weekly public pronouncements was probably a good thing for me.

UPDATE: The more I think about it, I guess it seems like a blogger comes off as a group discussion leader, an initiator among equals. Everyone feels invited to join in, whether to compliment, disagree, mouth off, whatever. Usually the topic is one of common access: “I saw the movie Blick last night, Brad Pitt was great but the plot was awful,” and so everyone can say, “Really? I thought Pitt sucked,” and like that. But if I’m sitting here with materials you can’t get, and I’m telling you information that’s been secret until now, readers can’t contribute out of their own store of knowledge. But they feel they have the right to say something, so they write in and say the piece I’m analyzing sucks, or improvisations should never be transcribed, or my feet stink, or else they pick up on some passing comment that refers to something they’re familiar with. It’s just not a top-down medium. It’s not an efficient one-way information transfer. Even a blogger as high-powered as Salon’s Glenn Greenwald is usually commenting on news reports or documents that are out there, that he can link to, so it’s not his private information. If he were getting confidential communiqués from the government or something, I guess people would be up in arms attacking his veracity.

Still one great things about blogs for musicology: when you need to put up audio examples, as I did with Dennis Johnson’s November, there’s just nothing like a blog.

Fellow Space Cadets

Today we finished mixing and mastering the Relache ensemble’s compact disc of my suite The Planets. I also recently finished my new piece The Rite of Spring, and am hard at work on one called Scheherazade. From now on I’m only using titles that have been pre-tested for widespread audience appeal.